Donovan Warren stands center stage at The Rail Club, looking every bit the part of metal-band frontman: H.R. Giger-inspired motifs tattoo his arms. A pair of dice and an alien eye decorate the back of his hands. The words "Last Call" bleed from his fingertips. His long, blondish-brown beard is braided, and a black bandanna imprinted with brass knuckles wraps around his bald head. A Black Label Society vest over a dark T-shirt, camouflage shorts with chains connecting to a wallet and a pair of black Converse complete the image.

He leans forward and prepares to sing his band's signature song, "Drunk On Blood." Most of his songs are inspired by 48 Hours and other murder shows. But it's 100 Proof Hatred's grueling tone and Pantera-inspired dress that keep people coming back. From bassist Jerry Galvan's black cowboy hat with a skull and crossbones patch in the center to guitarist Dave Lewis' Black Label Society ball cap, they were born into the heart of Southern metal in Fort Worth, and its influence is apparent not only in their look but in the power chords that anchor their arsenal.

It's a Saturday night, March 2012. Warren and the guys are plowing through their set before one of the largest crowds The Rail Club has ever seen, many of whom have been watching this band for years. It's the ultimate local metal band.

From the outside, The Rail Club looks like some out-of-business storefront, but it comes alive inside, with dim lighting and metal pounding from the speakers. There are pool tables and dart boards, a wraparound bar and a small stage. There's a dance floor used more often as a mosh pit. A picture of the state of Texas with a red, white and blue calf skull hanging on a guitar neck serves as the club's banner, and a nice reminder of what this place is: a mecca for metal.

Tonight that means playing host to the War of Rock's "Wild Wild West" contest. The winner will be crowned the "New War of Rock Band," a rare chance for a struggling local band to tour "Rockin' The Red Carpet" with Vince Neil, lead singer of Mötley Crüe. There are other perks, and a cash prize of $25,000. Metal bands from as far away as Alabama and Nashville are here, and this is just one of several battles across the region. The winner will square off against the nine winners of each local competition, and the winners of that will go to nationals.

Warren paces across the stage, glaring at the crowd. "What's happening 'War of Rock,' Fort Worth, Texas?" he roars into the microphone. "You're in the right place at the right time. This is a badass party. Everybody get fucked up, and don't go nowhere."

He makes a fist with his tatted hands, moves across the stage and stops at the edge of the swell of bodies surging forward and back like a tormented wave. Warren joined 100 Proof Hatred just as it was forming in 2005. "Play with some damn conviction" was the band's motto, and no one was more passionate about the lifestyle than Warren, who'd perfected his stage presence as a strip club DJ. He works the crowd as if they are customers at one of those clubs. Some of them are.

When the band finishes its set, Warren stands center stage to hear the judges' comments. His hands open and close into fists; his muscles twitch as he clenches his jaw, bleeding aggression, waiting to be judged. Mark Slaughter, founder of the metal band Slaughter, starts.

"All I can say is that Dimebag is smiling his ass off in heaven," Slaughter says. Warren smiles, flexes his muscles and bows, and the crowd screams its approval. To be compared to Pantera's late guitarist, "Dimebag" Darrell Abbot, is the highest honor a person can bestow on a Fort Worth metalhead. "Seriously, man, that was fucking cool," Slaughter continues. "The back half of that was like a dinosaur had just walked through the room. Rock on, man, you guys have got the heart, and you've got where it's coming from. It comes from the street, and it smells like a fucking concert, so that's even better."

Warren leans down and kisses a fan's cheek.

"Y'all rock, man," says judge Greg Ingram, co-creator of War of Rock. "Dime is smiling right now. Are y'all ready? I think you are."

Warren makes the universal metal hand sign and bows again. He appears lost in the moment, as if he's forgotten the disease ravaging him, the accusations, the investigation. To his fans and friends, he's a rock star. He's the life of the party, a "good-hearted" guy who'll give you the shirt off his back, open his door for you, fire up his grill for you.

"Thank you, gentlemen," says the final judge Claudia Rene, an actress and model. "100 Proof Hatred, huh? You guys own the crowd." The crowd screams even louder. "The War of Rock told you to bring it, and you brought it. You and your style —"

She stops and smiles hungrily.

"You're playing with my emotions right now."

He was sitting in the DJ booth, cuing up songs for the showgirls of the Texas Cabaret, when Jordan first saw him. She loved the way he wore his bandanna low, the chains connecting to his wallet, the ink that screamed rock 'n' roll. Some of the other strippers thought he was an asshole and warned her to stay away. He'd been convicted of assault, and two years earlier, a police report shows, he'd been accused of dragging his girlfriend by the hair and slamming her head into the floor. (The case was eventually dropped.) But there was something about the way he looked at Jordan, looked through her, like he could see past the mask she donned when she stepped in that club. ("Jordan" is a pseudonym.)

She looked too young to be a stripper. Her light blonde hair was perfectly straight, and her slight frame was draped with tattoos: a nautical star with wings across her chest; a silhouette of her walking the railroad tracks as a child with her grandfather on her side; the caterpillar from Alice in Wonderland smoking a hookah on her stomach. Stripping wasn't what Jordan had planned growing up in Weatherford, a rural community west of Fort Worth. She used to ride her bike to a creek at the end of her neighborhood and look at her reflection in the water. She saw a soldier staring back. She planned to join the Navy after high school.

She never finished high school. She was 17 when she started working as a club hopper, waitressing at various strip clubs. Her mom moved to Georgia to be with another man, so Jordan moved to Fort Worth. She made good tips as a club hopper, but management kept hounding her to dance. On her 18th birthday, she says, she took off her top and took the stage. One time turned into five nights a week, and soon she was numb with booze and pills whenever the DJ called her name.

One night, after a dance, Warren called her over. He asked the "house mom," the older woman who wrangled the young strippers, to take a picture of them with his cellphone. Standing next to him, Jordan felt herself drawn to him. He sounded like Dimebag and talked slowly, drawing her helplessly into conversation.

Their connection grew. Then, one night at the club, one of the bouncers, Cliff, was trying to break up a fight when he fell to the floor, clutching his chest. He looked at Warren, who quickly knelt next to him. "Man, I can't breathe," Cliff said, and started vomiting. People swarmed, but everyone froze. Warren scooped vomit out of his friend's mouth and performed CPR, but by the time paramedics arrived Cliff was dead.

After everyone left, Jordan walked into the DJ booth, leaned forward and kissed Warren on the cheek. "I'm here if you need to talk," she said.

He did, and they did, sharing their stories. Warren's mom was a stripper, and he'd been working as a strip club DJ since he was 17. The strip club life was in his blood, as were the chemicals that often go with it. "Warren ate Xanax every day of his life," says Joey Jones, a friend. "He had an incredible tolerance for those things. He could eat a dozen of those a day and still drive a car, even though he didn't drive a car."

He partied with women — always different women — long into the night, but always managed to make band practice and showtime. "It was pretty amazing to see that kind of activity, that many different girls all the time," says guitarist Dave Lewis. "Just running the numbers in your head, you would know that's a dangerous lifestyle, regardless what anybody says or whatever. Your chances of being exposed are greatly increased."

But there was something special about Jordan. In late 2008, he invited her to attend a GWAR concert at the Palladium Ballroom. He pushed their way to the front of the stage, and they spent the rest of the night hanging off the rails as the band destroyed the stage in their signature demonic costumes. They even got slimed. It was a good date.

Soon they were inseparable. They grilled out for Sunday football, played beer pong and watched thunderstorms together. They lived together, partied together, worked together. They just couldn't shake their addiction to alcohol and pills, or their jealousy. Warren hated her stripping; Jordan hated his hanging out with strippers. Mental, physical and verbal abuse ended many of their conversations, Jordan says. One night, she was mad at Warren while he was playing on stage, singing his song "Betrayed." She motioned for him to bend down and ripped out half of his beard. As his adult son (from a previous relationship) tried to throw her out, the whole crowd flipped her off.

A few weeks later, Jordan says, she was driving down the road that led to their house when she saw him attempting to get into a car with a stripper from the club. She flew into a rage, hit the gas and clipped him with her car's bumper. He soared into the air and hit the pavement, injuring his leg.

Instead of driving away, Jordan jumped out of her car and rushed toward him. "I'm so sorry," she said. "I didn't mean to. I'm so sorry, honey. Whatever I —"

"Run, run, run," Warren yelled. He knew the police would be there soon.

Jordan wouldn't leave. As the ambulance took him away, the police took Jordan to jail. She spent more than a month behind bars and received probation for aggravated assault. It was her first felony.

Jordan and Warren couldn't see each other while she was serving time, so he sent letters addressed from "Papa Bear," proclaiming his love and asking God for forgiveness for the bad things they'd done to each other. He even asked her to quit stripping. He'd stand in the parking lot in front of the jail, waiting for Jordan to look out the window. She'd look out for a moment before being led back to her cell.

Jordan went back to Warren after she got out. It was about three months later that she started to feel it — symptoms that felt like the flu, only supercharged. Nothing to worry about, Warren assured her. It was flu season.

Jordan found out she was pregnant on Halloween in 2009. Warren cried, but not tears of joy. It wasn't, apparently, the momentous occasion he'd described in his letters. Not long after, he began accusing her of sleeping around. Some of his friends were also telling him that Jordan was prostituting and posting ads on Craigslist. They broke up a few months after she learned she was pregnant, she says.

Then, in April, a doctor told Jordan she had tested positive for HIV. She felt alone, dirty, nasty. She was numb, and she worried her unborn child would contract the virus. She called Warren.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I've been tested, but I'll get tested again."

If not Warren, where did Jordan contract the virus? She wasn't sure. She'd had a few slip ups in the past, but —

A few days later, he sent her a text.

"It's negative."

It was onstage with 100 Proof Hatred, bandanna low and stance aggressive, that Warren first caught Carol's eye. She'd seen him around the metal scene, and she wanted to meet him, maybe even fuck him, but not marry him. She was 29 and working as a real estate agent during the day, partying with friends and musicians at night. Life was good for a change. ("Carol" is a pseudonym.)

Carol had a look and vibe seemingly designed to ensnare Warren: smart and confident, long dark hair and cat-shaped eyes that accentuated her exotic appearance. She grew up in Flower Mound, but she'd been attending Pantera concerts and partying with bands since high school. When a mutual friend offered to set her up on a date with Warren in early August 2011, she naturally agreed. Warren, separated from Jordan for more than a year by then, agreed too.

They went to The Rail Club, and Warren was in his element. They hit it off, but then Carol felt unusually wasted after her second drink, she says. She found it hard to focus as the night progressed, and she eventually blacked out and woke up the next morning in Warren's bed.

She only remembered bits and pieces of their sexual encounter. She knew she should be angry, but she found him charming, even if it would never lead anywhere. "I never saw myself with him like that," she says. They kept dating. She went to band practice and shows and liked most of his friends. It was fun for almost a month.

But in late September, Carol got sick — supercharged flu symptoms just like Jordan, plus other symptoms of an STD. She went to the Tarrant County Clinic in Fort Worth for treatment, worried she had herpes. "It's probably that," the doctor told her, and sent her to the lab for testing. She requested a full checkup, including an HIV test.

Carol had always been careful. She had annual checkups, including one before meeting Warren. But this time, when the doctor returned, a nurse took Carol's 6-year-old daughter out of the room. She'd tested positive for both herpes and HIV.

Tears streaming, Carol rushed back to the house where Warren was staying, left her daughter in the living room with his roommate and took Warren into the back bedroom.

"I'm HIV positive," she said.

This time Warren switched tactics, acknowledging what appeared obvious: that she had contracted it from him.

"I'm sorry," he said. "I didn't know I had it."

He seemed sincere.

"I promise, I'll make things right." He moved closer. "I'll marry you," he whispered. "I'll take care of you."

"I thought this was my last opportunity to have any kind of relationship," Carol says.

Carol took Warren to his first doctor's appointment, at the CDC at the Tarrant County Clinic. When his results came back, he didn't just have HIV. He suffered from chlamydia, herpes, syphilis — and AIDS. It took approximately 8 to 10 years for HIV to become AIDS, the doctor said, meaning Warren had contracted the virus sometime between 2001 and 2003.

Warren reassured Carol he hadn't known he had the virus. "I promise, I'll make things right," he begged. Carol allowed him to move into her apartment. She began taking care of him, separating his pills in a divider and refilling them each day while managing her own medication. She also attended his doctor appointments and promised not to tell anyone about his disease.

"It was such a big thing to go through," Carol says, "and to be cut off from having to cope with it made it really difficult for me."

Warren continued touring, burying this new secret among the others. To friends and family, he and Carol were getting married because he was 44 and ready to settle down. He even stopped sleeping with other women, which surprised his friends. He was "domesticated," as some of them would say, all amazed by his transformation.

Carol felt torn and alone. She knew she shouldn't be with the guy who infected her. "He had to have known" were the words that lived on the edge of her thoughts, especially when she discovered Jordan and her claims that Warren was the father of her daughter. Carol asked Warren about it, but he just said Jordan was a crazy woman who ran him over with her car. "She just tries to ruin my life," he told her. "That's not my kid. She's just trying to say that because you're in my life."

Carol would eventually learn he was, indeed, the father of Jordan's daughter. But Carol believed his lies, even threatening to call Jordan's probation officer if she didn't quit harassing him. She kept separating his pills and attending his doctor's appointments and dealing with her illness alone, she says, while Warren partied with his band on- and offstage.

Then, she says, while attending a routine appointment, a doctor was looking through Warren's chart. He said, nonchalantly, "Well, you tested positive for HIV in early 2008."

"Excuse me," Carol said to Warren as the doctor left the room. "What's he talking about?"

"I don't know what he's talking about," Warren said. "If they said I tested positive at the hospital, they didn't tell me."

"Well, if that's the case, we have a serious freaking lawsuit," she said. "We need to get hold of them and get your medical records and stuff."

That was the last thing Warren wanted to do.

"It was my big red flag," Carol remembers. "That's when I started investigating."

In the years after they broke up, Jordan did everything she could to prove what she suspected — that Warren had knowingly infected her. Then, in March 2012, she discovered a post he'd apparently written on ECCIE, a message board for escorts and clients.

"Ever wonder what drives a man to sing in a band called '100 Proof Hatred'? Well, I love sex, drugs and rock and roll," he began. "Unfortunately, when you mix the three as much as I have, you're bound to come up with something. Fuck, I don't know if it was the needles from all the ink, or the stripper groupies that dig the bandanna, but I've got it — HIV, AIDS, the HIVVY, whatever the fuck you wanna call it.

"I've banged a lot of fucking strippers in clubs in the Fort Worth area. A fuckload. I party every fuckin' night now. Lately, I been hanging out and playin' pool at Fantasy Ranch in Euless.

"I'm sick, real sick, but fuck all those pills every day. So I hide my head with the blue rag and the hat. I grow my beard as long as I can and I've covered most of my body with ink. In the dark, you can't tell that the AIDS is coming on. You hear me cough and choke, but you just think I'm hungover from partyin'.

"Yeah, I take the dancers to VIP, and they climb right the fuck on. They have no idea what I'm packin'. Fuck it, man, this is rock 'n' roll, and I don't give a damn. I laugh at those straight-laced guys at Fantasy Ranch taking the same girls to VIP right after me. Rich college fucks you're gonna get it too, and I don't feel fuckin' sorry for you.

"As for the bitches? I already gave it to one of 'em. I see a pic of her on here all the time. She fuckin' hates me, but I got mine and you get yours.

"I figure if I'm living longer than my hero Dimebag Darrell, I must be doing okay.

"Dumbasses, I keep hinting with shit like 'It's my party I'll die if I want to,' but they never get it."

He finished his blog post with a picture of him in black sunglasses, his thick, tattooed arms draped over two young women, them hugging him close, him flipping off the camera.

Jordan confronted him about it through Facebook, but he denied writing it. People ignored her, she says, and dismissed her as a stripper stirring trouble. Then she saw Carol's Facebook post, which claimed Warren had manipulated her into keeping his and her infections private. A few days later, Jordan received an email from Carol. She wanted to talk.

They poured their stories into the phone, and Carol, at least, hung up the phone convinced, just as Jordan was, of a troubling fact. "I knew he did this to me on purpose," she says.

In late summer 2012, Carol and Jordan took their story to an assistant district attorney in Tarrant County. Carol brought copies of Warren's prescriptions, emails, text messages and medical records. After the meeting, she wrote another Facebook post, asking people if they had any information that could help the investigation. She worked the phones and tracked down email addresses, hunting for Warren's former girlfriends. She found some, including at least one she'd heard was infected, but none came forward to cooperate.

Jordan, meanwhile, took her jailhouse letters, medical records and a screenshot of that ECCIE post to the prosecutor, then returned home to take care of her and Warren's two-year-old daughter. As Jordan feared, their daughter had also tested positive for HIV. Her biggest challenge as a mother is now giving her daughter her medication. Once, as an infant, she stopped breathing after taking it. Jordan had to perform a "baby Heimlich," which led to a feeding tube being inserted into her baby's stomach. Every day her daughter squirms and cries when Jordan gives her medication, and every year the feeding tube has to be replaced.

Even though she and Jordan had reported Warren, Carol was afraid he wouldn't stop spreading the virus. The only reason he got tested in 2008, she says, was because his syphilis was out of control. And Warren often told her that he "wanted to go out like a rock star."

So on November 30, she published a blog post on TheDirty.com, alongside a photo of Warren:

"This is Donovan Warren, the lead singer of 100 Proof Hatred. I can tell you for a fact this man has AIDS. He has been knowingly giving women HIV for years now and has not shown any sings of stopping. ... We need to get this man's picture out there and let people know whom they are dealing with. We are currently working with the District Attorney to have charges brought against him but until then please help spread the word. Stay away from this creep!"

"I wanted to make such a loud point that you had to hear me," Carol recalls. The next year, Carol would move out of state, start a new job and, she says, meet a man who accepted her and her sickness. But in the moments after she posted her accusations, some of the reaction was as deafening as one of 100 Proof's power chords.

"Did you hear the whore posting this fucked Donovan within five hours of meeting him?" one person wrote.

"I have seen him through the years date lots of females, but I can promise they always threw themselves at him," wrote another.

"I hope whoever posted this rots in hell! He did his best to inform everyone that he had it. He did not knowingly spread this! That wasn't the type of person he was!"

Bill Vassar, an assistant district attorney in Tarrant County, disagreed. The case was reassigned to his desk in the spring of 2013. He reviewed the evidence compiled by Carol, contacted Jordan and reached out to the other victims Carol and Jordan had located. He eventually concluded that Warren knew he was infected before he started dating either woman, and that he'd admitted it in that ECCIE post. "Based upon our investigation," Vassar says, "Donovan Warren knew he was HIV positive since March 6, 2008."

That spring a grand jury indicted Warren on four counts of Aggravated Assault on a Family Member with a Deadly Weapon, a first degree felony. Warren was arrested on a Saturday in June at The Rail Club, in front of his family, friends and band members. His bond was set at $5,000. A friend, Derrick "D-Rock" Walker, spoke with him not long after he bonded out. "I don't know, man," Warren told him. "It has something to do with someone named [Carol], but I don't know anyone by that name."

When Warren failed to appear at his first hearing, a new warrant was issued — only this time the bond was set at $10,000, which might as well have been a million dollars to someone who, according to court documents, spent the last five years earning $150 a month. That July, Warren was living in his mom's RV just outside of Azle and working odd jobs for people who lived in the RV park. For two weeks, his mother, Judy Helton, had seen the unmarked cars watching the small RV park. She told her neighbors, "Somebody's been watching us." They replied, "You're just being paranoid." Then one day, she was sitting in her car, talking to her son, when patrol cars swarmed her home. The police officers made her get out of the car as they arrested her son and left her standing in the middle of the dirt road as they took him away.

The last night Warren took the stage at The Rail Club in October 2013, no one knew it would be his final performance. He was decked out in metal glam, and his long, braided beard was still streaked with red dye as a tribute to Dimebag. He seemed in good spirits as he fell into the rhythm of his music.

Warren had tried to kill himself a year earlier, around the time of his first arrest, by overdosing on a mixture of alcohol and Xanax. Paramedics arrived in time to revive him, says friend Jennifer Norred. He told some of his friends that he didn't mean to do it; he'd just been partying too hard. But he told Norred, his former roommate, he'd tried to kill himself because he'd been fighting with Jordan, who had just discovered that he knowingly infected her and their unborn daughter with HIV.

Warren hadn't planned to tell anyone about his illness, but when Carol posted on Facebook that he was knowingly infecting women, he had no choice. According to bassist Jerry Galvan, Warren told everyone at a Labor Day barbecue party at Norred's house. "Yeah, it's true," he told them. "I've got HIV. I've been trying to keep it a secret, but it came out anyways." He didn't mention he was dying of AIDS. Galvan says Warren didn't tell anyone because he was afraid people were going to treat him differently. "But I just told him, 'Man, I've known you for 20 years, why would I treat you any different?'"

That night at the Rail Club, as he rushed across the stage, Warren seemed to have forgotten the way his life was quickly crumbling in on itself. His trial was fast approaching. Fantasy Ranch and other strip clubs were refusing him entry, and some of the rock clubs were following their lead. Rumors were spreading throughout the metal community. It was just a matter of time before the truth was fully revealed.

Two weeks after that last show, Helton says, Warren was drinking with a neighbor in the RV park when he fired a few shots at a target with the neighbor's gun. He was depressed, she says, because he wasn't practicing or playing gigs. He felt like his exes were bullying him, and he thought they were calling the clubs and spreading lies.

"I could see it happening," Helton says, "and I was just begging him to hang on, please."

The gunshots woke her.

She put on a coat and walked to the neighbor's house two doors down.

"Did y'all hear that?" she asked.

"No," they said.

"Donovan, you need to go on home."

She knew he shouldn't be drinking.

Warren wouldn't listen.

His mom went back to the RV and tried to sleep.

When he finally did come home, Warren climbed into his loft, shut the curtains, pulled out his cell phone and started recording. He looked up at the pictures taped to the ceiling, of his older daughter from a previous relationship, of family, of friends. He started recording them. He stopped at each and lingered for a moment, as if trying to lock the memory away. When he made it to the last one, the picture of his daughter, he turned his cell phone around. He wasn't wearing his usual bandanna, just a black hat turned sideways. His eyes looked sad, not angry. He started whispering.

"I've had a good life. I love everybody. I love my mother. I love my children. But I can't take this bullying anymore."

He dropped the cell phone. It was just then, Helton says, that she pulled back the curtain and saw him trying to hide the gun he'd just pressed to his head.

"Donovan, is that a gun?" she screamed.

"No, it's not a gun."

"Oh, Donovan, I know that's a gun. I'm going to go get help."

She rushed to the neighbor's house, but by the time they got back to her RV, Warren had already pulled the trigger. Neighbors came pouring through the door of her RV. One of them was a girl he'd started seeing recently. She climbed into the bed and put his head in her lap. Someone else said, "Get a towel." His mother was hysterical and saw the gun next to him and told somebody to get it out of there.

"He'd shot himself in the temple," she says. "The bullet came out both soft spots. I knew from forensics TV that that was a fatal wound, even though he was still breathing. I knew that was fatal.

"Ten-to-one, if nobody had been there, I might have turned that damn thing on myself just out of insanity," she says. "I mean, the love of my life, everything to me, was gone. I'll never see him again. I knew it was them girls."

Paramedics rushed him to Texas Health Harris Methodist Hospital in Fort Worth, where doctors performed emergency surgery just after 10 p.m. It was after 2 a.m. when they finally finished. Warren lost his eyesight and the part of his brain that controlled function and memory. He would forever be trapped in a vegetative state.

Later that night, 30 people stood around Warren while his older daughter, Christian, held his hand. A white bandage was wrapped around his head, covering his eyes.

His mother turned and looked at someone standing next to her. "Look at that, man, he's still got a bandanna on."

When everyone had finally arrived, the doctor came into the room and said, "Judy, are you ready?"

She looked at everyone. "Are y'all ready?"

"Yeah," they said.

"OK," she answered.

The doctor turned off the life support machine.

"You don't die right away," Helton says. "You don't take a last gasping breath. It took him about seven minutes of gyrating, his whole body lifting up because he wanted to live. To me, it was almost like an electrocution, and right there, I thought to myself, whatever he has done in his life, he has paid for and that's what I want people to know, too."

Warren was pronounced dead at 11:17 a.m. He was 45.

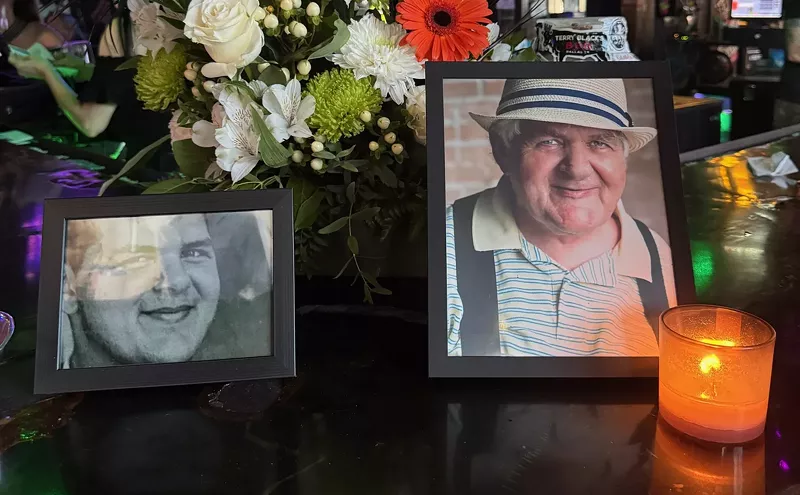

They held his memorial at The Rail Club. His mother had the body cremated and poured some of the ashes into small heart-shaped lockets. A former roommate led the memorial service, and friends wore Black Label Society vests in his honor.

Before he died, Warren sent a text message to Jordan and said, "If I could take this all away, I would." The assistant district attorney eventually closed his case.

"I had mixed emotions when I heard he committed suicide," says prosecutor Vassar. "On the one hand, I was glad he was dead so he couldn't infect anyone else. On the other, I thought it was too easy for him. He took the coward's way out and deserved to spend the rest of his life in prison." Later, Vasaar received a call from a mother of a local college student in Arlington, who accused Warren of sexually assaulting her daughter. "She was obviously concerned for her daughter's health and whether she had been infected with HIV," he says.

The prosecutor told Carol and Jordan about Warren's death.

"It was bittersweet," Jordan says. "But then that was selfish of me. I should have thought of my child first. She'd just lost her father even though she was never going to know him."

"I was sad for his kids," Carol adds, "and angry he took the cowardly way out, but relieved I didn't have to go through the emotional burden of trial and fear of him or someone trying to kill me before trial."

Of course, a trial could have vindicated Jordan and Carol, who to some will always be the "junkies" and "groupies" who bullied Warren into suicide. Another ex even started a "Justice for Warren" Facebook page, posting several links about bullying and HIV. An anonymous user wrote on the TheDirty.com post, "Donovan found a loophole to heaven: his mother pulled the plug."

After a brief hiatus, 100 Proof Hatred invited Warren's best friend, D-Rock, to become the lead singer. They played their first show in February of this year. Around the same time, when they learned a story was being written about their old bandmate, they posted a Facebook comment distancing themselves from Warren's personal actions.

"We just want everyone to know that, whether it's good or bad what Warren did in his personal life was his business! We love our brother, and we just want him to Rest In Peace, and we want to remember the good times on and off stage! He has met his maker and ONLY JUDGE and let's just leave it at that!"