Last week President Obama banned certain types of equipment from federal grants to local police agencies, ruling that the federal government would no longer provide cops with tanks, bayonets, grenade launchers, ammunition of .50 caliber or higher and some types of camouflage uniforms.

The president said: "We've seen how militarized gear sometimes gives people a feeling like they are an occupying force as opposed to a part of the community there to protect them."

I get the tanks and bayonets. Not sure about the camo. Do I care, should I care what kind of clothes cops wear?

Last week I talked to two people I have known to be really smart on the topic of cops. I didn't actually ask them the clothing question, but I think I came around to it from another perspective. I was asking them what kind of person police agencies should recruit for the job.

"We want the model citizen who wants to go into public service and make our democracy work."

tweet this

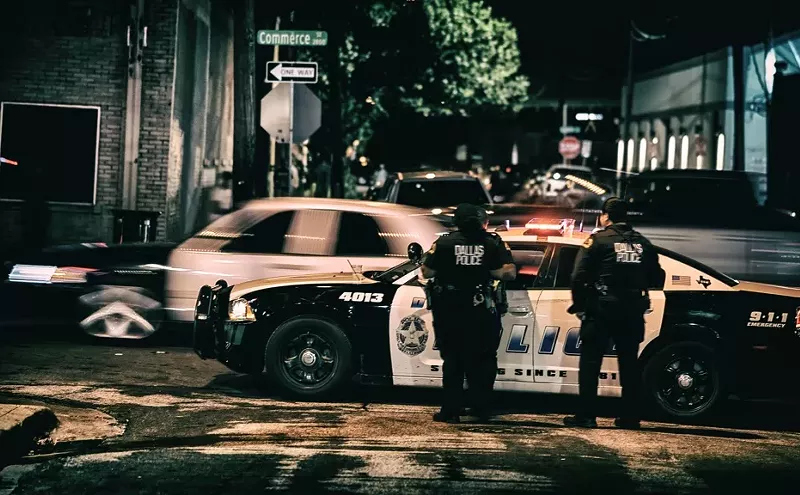

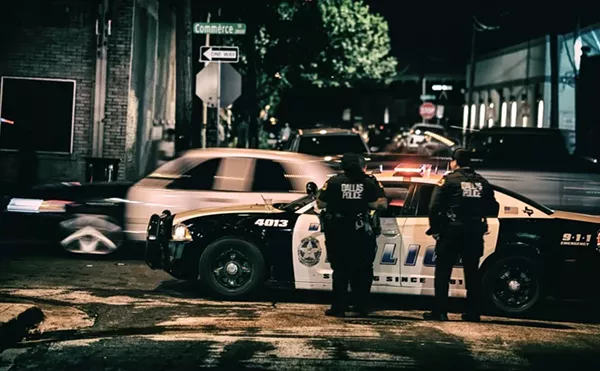

Dallas Police Chief David Brown told me the person he does not want to recruit — in fact he wants to screen against this type in the recruitment and training process — is "the person who wants adventure."

He said he understands why police work is enticing for that type. "We get to do really exciting things," he said. But in today's world, he said, putting a uniform, badge and gun on an adrenaline junky is "asking for trouble."

Instead, Brown told me, "We want to have people who have a sense of public service, who want to help, people who have a high moral standard. We want the model citizen who wants to go into public service and make our democracy work."

Former Dallas Police Chief David Kunkle told me that the importance of problem-solving ability and of people skills in a cop's makeup is a reflection of what the job really is, as opposed to what it looks like on TV.

"Police officers, in particular young officers, want to define themselves as crime fighters," Kunkle said. "If you spend much time with an officer, you find that they spend relatively little time dealing with the way people typically think of crime, which is an unknown suspect robbing or burglarizing or stealing or assaulting somebody where there is not a relationship with each other.

"But what police mainly do is respond to conflicts between people. They are kind of a people problem solver more than they are a crime fighter. I think as officers mature in the job, they tend to see their jobs differently."

So that's all about the ideal. We want a cop to be a Boy Scout or a Girl Scout, kind of like an armed clergyman who can go out there and help the Cossacks and the Bandidos see how much they have in common and persuade them to work on their bikes together instead of shooting up the Twin Peaks restaurant.

Sure. But both Brown and Kunkle are veteran street cops themselves. Both of them know exactly where the idealism ends and reality sets in.

Brown told me he knows full well that the re-education of a new cop starts the minute he leaves the academy and takes the shotgun seat in a car on the street with his trainer. The trainer, a veteran cop, tells the new recruit that he needs to put all that high-minded idealistic bullshit from the academy out of his mind right now if he doesn't want to get himself or his trainer killed.

"The trainer teaches the new officer to live in a world of what's possible, not what's probable," Brown said. He gave me an example.

We had met to talk in a coffee shop across the street from police headquarters — a cool little hippie joint in the basement of the South Side on Lamar building. The only other people in the place were a man and a woman several tables away who looked like they were talking business and a guy on the other side of the place sipping a cup and listening to headphones.

Brown pointed out to me that when he came into the coffee shop he seated himself so that he could watch both doors. The probability was extremely low that somebody would come into that place shooting. But the possibility existed. If you're a cop and you do this stuff all day and you want to go home every night, he said, you operate on the basis of what's possible, not what's probable. And how does that affect your skills as a clergyman in blue?

Kunkle told me he sees an inevitable conflict between management's legitimate desire for cops who can calm the waters and the legitimate desire of rank and file officers not to get killed. He told me about a gathering in Virginia recently where police of all ranks met to discuss the needs of police agencies.

"Society expects a police officer to resolve all the broken social service safety nets."

tweet this

"When you talk to commanders," he said, "it was all people skills and problem solving and that kind of stuff. But from the officer's perspective it was tactical training and defensive tactics. So they saw what was most important to them differently than what management saw."

I shared a little of my own disquiet about these things with Brown. I told him I looked at incidents like Ferguson, North Charleston and Baltimore and compared them with my own experiences getting to know people on the street in tough parts of Dallas.

I said, "Some kid drops out of high school still not able to read, sells dope, gets caught, goes to prison. Whatever trade he learns in prison is a bitter joke, because when he gets out he finds out he's not allowed to have a real job, ever, because now he's an ex-con. We basically tell that young person, 'Go away, your life is over.' He hooks up with a zillion other guys on the street who are in exactly the same shape. And then we tell the cops, 'Hey, go down there and take care of that situation, will you?'"

Brown said, "Society expects a police officer to resolve all the broken social service safety nets. We are the social service of last resort. It's up to us to resolve the lack of mental health funding and every other social problem."

And cops don't get to do it from the office, he said: "We still make house calls. We see the very worst in people. I honestly wonder sometimes if we ask too much of officers. It's not natural to be doing what we're doing all day."

He said he urges police officers to seek experiences and contacts that can provide balance. "That's why I tell officers they need to have non-police friends. They need to keep going to church. If they like to hunt, they need to keep doing that, although I don't know why they want to kill Bambi."

In what both chiefs had to tell me, I heard the conflict between mission and reality, the academy and the street, making it a better world and making it home that night. But both of them wound up saying the same thing: Somebody's got to do it, it's got to be done right and the right way is never going to be for cops to think they are an occupying army,

"It's not a job for the warrior mentality," Brown said. "Instead, we are guardians. We're not at war with our communities. It's just the opposite."

So, back to the business of camo, tanks and bayonets. The president's directive was a clear response to recent police shootings. In the worst of them, we have all been exposed to a side of police action most of us would never have glimpsed but for the invention of cell phone videos, dash-cams and body cams.

An especially disturbing incident for us here in Dallas was the killing of Ruben Garcia-Villalpando, 31, by a Grapevine police officer. Garcia-Villalpando, drunk, was walking toward the officer with his hands on his head, ignoring the officer's repeated commands to stop, when the officer shot and killed him.

The dash-cam video reminded me of another dash-cam video I had watched recently on YouTube. A man who seems dopey and out-of-it insists on getting out of his car, ignoring an officer's repeated commands to stay in the car. Halfway out of the car, the man lifts a handgun in both hands and shoots the officer in the face.

I thought about what Chief Brown had told me — living in a world of possibilities, not probabilities. What was the probability that the drunk idiot who kept climbing out of the car was going to suddenly snap out of it, flip a handgun up in a two-fisted military pose and shoot the officer repeatedly? That probability had to be tiny. But the possibility was the one big number. Number One. Dead or alive. You or me.

I also thought about what Kunkle told me — the day in, day out life of the cop and what it's all about. It's almost never the gunfight at the O.K. Corral. It's a visit to the home of John and Wanda Doe, where you have been six times in two months, so Wanda can accuse John of beating her, so two weeks from now Wanda can tell the grand jury that John never laid a finger on her and that damned cop stirred up all the mess.

Or, this: It's John and Wanda's kid who's not learning to read, and somehow you reach him, and somehow he straightens out, and his life is not lost or wasted, because of you.

But John definitely has a gun.

Both chiefs are right. The world cops occupy is not natural. It's impossibly complex. Right now I'm voting no on tanks and bayonets. I want to vote no on camo, too, but I am nagged by the possibility that I may still have no idea what I'm talking about.