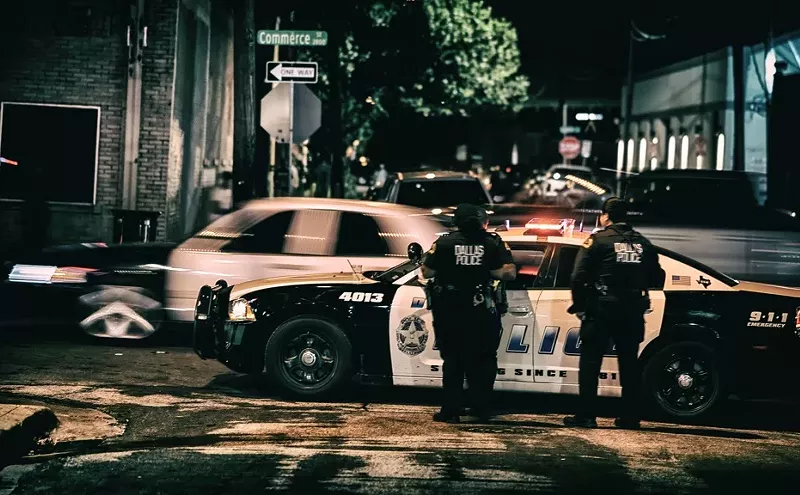

When Deputy Chief Gary Tittle formally announced the Dallas Police Department's new downtown panhandling crackdown on Monday, he was careful to define the target of the operation as "that aggressive panhandler, the one approaching an individual demanding money, asking for money, impeding their walkway on the sidewalks, getting out into the street, on the curbs, moving out into the highway from the shoulder of the highway."

To a certain extent, the narrow focus on aggressive panhandlers is simple pragmatism. They are the ones that can make walking downtown sidewalks feel like running a gauntlet; the guy politely asking for change is a comparatively minor annoyance. But there also seems to be a good deal of legal ass-covering at work, a hint of which could be picked up in Tittle's description of aggressive panhandlers. Most of the actions he described (i.e., wandering into a roadway) can be construed as illegal in their own right, regardless of whether an individual is asking for money.

This is significant because prosecuting people for panhandling triggers certain constitutional questions, the answers to which aren't terribly favorable to places that outlaw the practice. Asking for money — which, if you strip away the discomfort of passersby and don't count the hyperaggressive Darryl Davises of the world, is all panhandling is — is a form of speech that courts generally agree is protected by the First Amendment, even if the U.S. Supreme Court has never directly weighed in. Absent some offensive act (the Supreme Court has ruled that conduct doesn't enjoy the same protection as speech), the barriers to government curtailing any type of speech are high. Concerns that begging makes passersby uncomfortable or harms the perception of certain neighborhoods don't cut it.

And so, for the past quarter-century, cities have tried to craft panhandling bans that are narrow enough to pass constitutional muster while still being potent enough to effectively address the concerns of residents and business owners. Dallas designated certain downtown neighborhoods (i.e., the Central Business District, Deep Ellum, Uptown and Victory Park) as "solicitation-free zones" and banned panhandling within 25 feet of parking meters, pay phones, gas pumps, ATMs, DART stops, restaurants and car washes. Asking for money is also illegal between sunset and sunrise (the official times, according to city code, are based on the daily listing on Dallas Morning News' weather page), as is aggressive panhandling, i.e., "solicitation by coercion." The latter is the charge DPD appears to be relying upon during its crackdown.

In the past, Dallas might have been on reasonably solid legal ground. In June, however, it became much shakier after the U.S. Supreme Court ruled 9-0 that Gilbert, Arizona, had unconstitutionally restricted the speech of a small, itinerant church by limiting the size and duration of signs directing worshipers to its services while allowing campaign and other signs to be larger and remain up longer.

The ruling didn't address begging per se, but it subtly expanded the types of speech restrictions likely to be overturned on constitutional grounds. Treating speech differently based on its message was already a well-established no-no, a notion that had been baked into the Town of Gilbert's sign law. It was studiously viewpoint-neutral, treating all campaign signs, be they Democrat, Republican or third-party, just as it treated all temporary directional signs the same, whether they led to a small evangelical church or a gathering of atheists. In the majority opinion, Justice Clarence Thomas wrote that "[singling] out specific subject matter for differential treatment, even if it does not target viewpoints within that subject matter" is unconstitutional.

In case the implications for panhandling laws wasn't sufficiently clear, the court at the same time asked a federal judge to reconsider his decision to uphold a ban on aggressive panhandling in Worcester, Massachusetts, in light of the Gilbert decision.

"It used to be that, before Reed v. Gilbert, blanket bans were unconstitutional, but more nuanced, aggressive panhandling ones, depending on the wording, depending on what was at issue, those were making it through," says Eric Tars, senior counsel at the National Law Center on Homelessness & Poverty. "Since Reed, even the aggressive panhandling ones have been thrown out."

The first victim was an anti-panhandling law in Springfield, Illinois. A federal appeals court in Chicago had initially upheld the law but, citing Reed, reversed course and overturned it. The next month a federal judge rejected a Grand Junction, Colorado, law that, like Dallas' ordinance, banned people from asking for money after sundown or within a certain distance of ATMs and restaurants. In October, a Lowell, Massachusetts, law that banned panhandling in a broad area of downtown, echoing Dallas' "solicitation-free zones," met the same fate.

Some cities aren't waiting to be taken to court. Denver has stopped enforcing its panhandling law, as has Madison, Wisconsin. "Any city that has a panhandling law on the books should be taking a serious look at at least stopping enforcement and considering taking it off the books, because it's a sitting duck," Tars said in an interview last week. Five days later, DPD announced its crackdown.

Of course, sitting only becomes dangerous for ducks when there's someone shooting at them, which is to say that Dallas is free to crack down on panhandlers as hard as it likes until and unless some convicted panhandler files a lawsuit.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "21721571",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "21861991",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "22608066",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17357520",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]