The first time I activate the drone’s automatic takeoff, the speed of its four rotors and the animal-like way it leaps from the ground surprise me. The little aircraft, a DJI Phantom 3 Standard, has unexpected spunk.

It rises to 4 feet and halts, lights blinking expectantly. I experiment with the controls, a few hesitant nudges of the thumb controllers. The drone responds instantly and then starts to drift. I didn’t take time to let the drone get a GPS fix that allows it to automatically stay over a single point. The machine is smart, but only as smart as its operator.

The aircraft veers straight for a gaggle of gaping in-laws. Their laughter turns into shrieks. The drone hits a brick wall and falls to the ground, the impact of the still-spinning rotors on the home's foundation now making a noise like a wounded insect.

Emergency shutdown. One flight, one flyaway, two rotors chipped. It’s acceptable. Most lessons in drone piloting come with broken parts and fuselage scars — if you’re lucky enough to see the aircraft again.

I give my drone a working name, Observer-1. It’s suitably official, and the name acknowledges the mortality of the aircraft and an implicit commitment to buy Observer-2 in the event of catastrophe.

My plan is to fly the drone with its mounted camera in service of the Dallas Observer. But there are a slate of laws, state and federal, arrayed against this ambition. Flying the quadcopter in entirely harmless ways can bring thousands of dollars in civil fines and criminal penalties, including jail time, and there’s no worse state in the union than Texas to turn this toy into a tool. Learning to fly Observer-1 turns out to be the easy part. Breaking free of the red tape binding the drone will be something else entirely.

My Christmas flight violated federal law. In 2012 Congress passed the Federal Aviation Administration Modernization and Reform Act. At the time, the worry was that government sluggishness would get in the way of innovative uses for small aircraft. Congress knew that companies would want them for short aerial deliveries, police departments would need them for search and rescue, and university researchers could use them for any manner of research into animal behavior, Native American cliff art and so on.

Congress gave the FAA more than three years to create the system. The agency took the entire time and introduced its Registration and Marking Requirements for Small Unmanned Aircraft in December 2015. It requires all small unmanned aircraft, those weighing more than 0.55 pounds, to be registered with the feds. It says that failure to register an aircraft “may result in regulatory and criminal sanctions. The FAA may assess civil penalties up to $27,500. Criminal penalties include fines of up to $250,000 and/or imprisonment for up to three years.”

The FAA as of 2015 treats unmanned drones the same way as airplanes and helicopters. That number on an airplane’s tail that starts with an “N”? That’s the FAA registry, and it can be used to look up the owner and history of the plane.

How a Quadcopter Works

The trick to a quadcopter’s flight and control are the rotors, which spin in opposite directions. (Red blades here are moving clockwise while the blue ones spin counterclockwise.) When each rotor is at equal thrust, the quadcopter hovers. By adjusting the power of the spin of each rotor, the aircraft moves forward, rolls or banks without need of a tail rotor.

Unlike those other aircraft, there is no enforcement of the FAA drone registry system. Airplane pilots’ N-numbers are included in flight plans logged with air traffic control. Drone operators file no flight plans — which would be absurd — and really have no one to check our papers when we fly. Police could hassle us, but we’re not required to present our registration to anyone but a U.S. Department of Transportation official.

The only way the FAA will know that a pilot didn’t register is after he does something damagingly stupid and gets caught. And it’s harder to get caught if you don’t register. As of March 3, FAA spokespeople say, there have been 748,645 total registrations. With the FAA estimating one million drones sold in 2016 alone, that’s a pretty low rate of registration.

Making Observer-1 street legal is actually pretty easy. I access the FAA website, enter my information, the drone's specs and pay the fee. It’s just $5 to register, plus processing fees, with a renewal due in a couple years. Now I can fly my Christmas present without exposing myself to jail time.

But using it for professional work won’t be that easy. It’s not enough for the drone to be street legal; I will have to be registered, too.

US Aviation Academy is busy on the Tuesday afternoon I arrive to take the airman’s knowledge test. The academy is spread across several buildings and hangars along the runway of Denton Municipal Airport.

The main office, where a lot of standardized testing takes place, has a deck that overlooks a runway. From here, visitors can watch airplanes and helicopters come and go, most with student pilots at the controls.

Before the FAA set up the rules in 2015, operators needed a full pilot’s license to make money using a drone. This was, of course, an absurd amount of regulatory overkill. Operators are not allowed to fly drones where airplanes are. No wedding photographer needs to know how to be a pilot to do his job. And why does this license only apply to those who want to use drones to make money, and not the hobbyists as well?

To clear all of that up, the FAA laid out the requirements needed to receive a drone pilot’s license. Again, only those who want to use them for business need to worry about this license. Applicants have to be older than 16, subject themselves to a perfunctory Transportation Safety Administration background check and pass “an initial aeronautical knowledge test at an FAA-approved knowledge testing center.”

My knowledge testing center is the US Aviation Academy. The place is built to accommodate aspiring pilots, mostly from other nations, who are earning their wings in Texas’ excellent air space. The international flavor of the academy is everywhere. Posters of the Airman’s Creed line the walls in a dozen languages. An illustrated sign in the men’s room implores those inside: “DO NOT STAND OR SQUAT ON TOILETS SITTING ONLY!”

A note inside the men's room at the US Aviation Academy. Places that cater to international students must be explicit.

Joe Pappalardo

A cadre of Chinese trainee pilots sits with me outside the test center. The school has a contract with the Chinese government to train these students to earn their general aviation licenses before flying as commercial pilots for the state-owned airlines. The Chinese students are wearing neatly pressed uniforms and hold flight logs in their hands. A quick look at the logs shows just a handful of times in the air. They are in their 20s, and green as they come, but in the aviation world they have already eclipsed my drone-flying ass.

No matter the result, I will never be an actual pilot. The best that can happen is that I'll become a “remote pilot in command,” or RPIC.

The test booths are under video camera observation. If test takers need anything, proctors tell us, we are to wave our arms. Soundproof headsets, a calculator and scrap paper are provided. The booklet includes aeronautical charts and sample weather reports, the kind sent to pilots in cockpits.

I have two hours to finish 60 multiple-choice questions. Any score of less than 70 percent is a failure. My online test scores average about 75. I could blow this thing.

Some of the stuff is a breeze, real common sense gut checks about when it’s OK to use drugs and fly a drone (the FAA says never) and when it’s acceptable to fly within 5 miles of an airport (never without permission). Then there’s the rote-memory stuff, to prove you’ve been paying some attention. These are the stats that the FAA feels you should memorize, like the numbers of various federal statutes, the 400-foot flight ceiling for drones and the attributes of alphabetically designated types of airspace.

In the real world there are apps, including one from the FAA, that will tell you if there are any airspace restrictions for flying drones based on your GPS coordinates. The one I use has weather conditions integrated as well, so I’ll be warned if there will be rain or if the winds will be too high. But this is the test booth, and the feds want me to appreciate the intricacies of the system they created.

The mismatch of relevant knowledge and test material is apparent when the test asks about the arcane language of the markers painted on airport runways. I grit my teeth. If a drone operator flies within 5 miles of an airport, he is violating federal law, so when would I need to know what direction runway 9 is facing? (The answer is east, by the way.)

The Chinese pilots complete their tests before I do. They wave their hands in the air and sit still until the proctor fetches them. I check the clock and see more than an hour remaining. I make a half-hearted attempt at double checking some answers, decide my fate is sealed, and wave my arms at the camera.

The results come in minutes. They print out the score and the proctor says, “Congratulations.” I score an 87. I wouldn’t trade my position with any Chinese pilot. I am an RPIC with an entire newspaper website at my disposal. The possibilities should be limitless.

But then I fly straight into the headwinds of the Texas Privacy Act.

Drone footage of pig blood discharged into the Trinity River, lower left, in 2011.

courtesy sUAS News

The company beat the charges — county officials trespassed during the initial investigation — but the case became a watershed example of how unmanned aircraft could be used for environmental activism, citizen journalism and media reporting.

Two years later, the Texas Legislature created a law that appears to make all that sort of thing illegal. The 2013 Texas Privacy Act specifically calls out drones for special restrictions. The law includes guidelines for criminal and civil punishments: a Class C misdemeanor “if the person uses an unmanned aircraft to capture an image of an individual or privately owned real property in this state with the intent to conduct surveillance.”

The civil action section is more broad, saying “an owner or tenant of privately owned real property located in this state” can bring legal action against a person who captured an image of the property, owner or tenant. Penalties start at $5,000 for capturing an image, $10,000 for the display or distribution of any images and recovery of “actual damages” if the drone operator “distributes the image with malice.”

The Texas Privacy Act has exemptions that protect specific commercial uses. The exemptions read like a list of preferred Texas industries. Oil and gas companies can use them to inspect pipelines. Energy companies are also allowed to inspect natural gas equipment. Engineers and real estate agents have specific loopholes. Universities can fly drones while conducting research. Other states that passed similar regulations restrict law enforcement’s use of drones, but Texas’ law stipulates that the police can use them without obtaining a warrant.

The Legislature, alas, left journalists off the list of these exemptions. Which is a shame, as the website of the Professional Society of Drone Journalists will tell you. “Being much less expensive and safer than news helicopters, they enable independent journalists to cover important events from a valuable perspective," the group says. “Drones will enable journalists to obtain data and provide independent verification for the public good, where before only governments had the ability or authority to do so.”“If we need to adjust the law, I definitely wouldn’t be a hard ‘no.’” — Lance Gooden, sponsor of the 2013 Texas Privacy Act

tweet this

But Texas law leaves me with some thin options when it comes to using Observer-1, things that a traditional news photographer doesn’t have to bother with. It’s not clear what the law means.There are many possible interpretations and no legal cases in the state to clear them up.

I call state Rep. Lance Gooden, who sponsored the 2013 legislation, to find out some backstory. I’m prepared for a spirited disagreement over privacy. Instead, I get a reasonable and rational rundown of the law’s intent as he saw it and hear his willingness to “re-evaluate priorities on drone issues.”

I suggest that his legislation may have aged poorly, now that the feds have issued some parameters. “The FAA regulations definitely help,” Gooden acknowledges. “Four years ago, there was no guidance.”

If a journalist rented a helicopter numerous times to take photos of ongoing illegal dumping on private property, they would not violate the Texas Privacy Act. But if I do it with a drone, even as low as 8 feet in the air, I’m liable to be arrested. And I am in the distribution business, so the higher civil fines would apply when the guilty party sues me and the paper.

Gooden’s problem with drones is that they are subtle and persistent. Lawmakers feared that the small and relatively quiet drones offered new risks that required a specific law. “You don’t always know a drone is there,” Gooden says. “You could park it over a home and leave it there to hover 24 hours a day. A helicopter or even a guy on a ladder, you would be able to see them.”

With the small battery charge of Observer-1 taken into account, I’d need 48 battery packs at $150 each to keep it airborne over a home for an entire day.

He puts a lot of weight on the word “surveillance” to limit the criminal penalties to nefarious uses — although a district attorney could define a journalistic investigation as surveillance in order to make a case against a pesky reporter or citizen. The legal definition of surveillance is “an investigative process entailing a close observing or listening to a person in effort to gather evidentiary information about the commission of a crime, or lesser improper behavior.” Sounds a little too much like reporting.

Let’s say a reporter uses a drone to compare the police department’s response to nuisance calls in two different neighborhoods. If the cops don’t like the footage, they could choose to ring the reporter up on the misdemeanor, he’d lose his FAA license and be grounded.

Gooden seems surprised at the restrictions. He says he never intended to stop media from covering breaking news with a drone. “If there’s a police standoff, you could cover that,” he maintains.

But that’s not exactly how most attorneys, including the Observer’s, interpret the broad language of the law. The civil penalties enabled by his law don’t appear to be restricted to just surveillance. The law is broadly enough written that it seems to prohibit taking any images of private property without permission. By filming that standoff, I’d be opening my paper and myself to a civil lawsuit from the property owner or his neighbors.

“If we need to adjust the law, I definitely wouldn’t be a hard ‘no,’” Gooden says. “I know that in this session several of my colleagues are introducing drone legislation. I’m not, though. I’m really focused on education.”

He’s right; there are drone bills being considered in the Legislature this year. However, it’s still hard to find one that is seeking to loosen the laws, rather than tighten them. One bill aims to classify correctional institutions as infrastructure, to give authorities a new way to crack down on contraband drone deliveries to jails and prisons. Another challenges the law’s allowance of drone monitoring of private land 25 miles within the border.

I seek a Texas defense attorney with some interest in this and find Benson Varghese, managing partner of the law firm of Varghese Summersett. He points out that creating exemptions for “journalists” would form a loophole that would gut the law. “How would a legislator define the exception in such a way that everyone does not claim they are a journalist?” he asks.In many ways, drone journalism is the epitome of everything critics and old-school newshounds complain about: flash over substance, amateur image-taking over photojournalism, distance over intimacy.

tweet this

It’s an annoyingly sharp point. When everyone has an outlet, everyone is a journalist. And this time everyone has been swept to the curb. Reporters and the general public, none of us are to be trusted with flying cameras. Not the drones, mind you, which can be flown in many places as long as they are not recording. This is a public privacy law, not a public safety law.

There is an inherent weakness in the law that Varghese sees, but it has never been challenged in court. “In terms of state or local regulations outpacing federal regulations, it is important to point out most airspace is controlled at the federal level,” he says. “Regulations to ban operation, restrict flight plans, or flight altitude generally need to get federal approval or risk a challenge in court based on federal preemption.”

For a while I harbor a dream to fly Observer-1 on some hot story, get sued for it despite my unimpeachably responsible operation and win the court case that defeats the Texas Privacy Law. But then I make the mistake of mentioning this fantasy to the newspaper’s attorney.

He says three words that dash the dream: “It sounds expensive.”

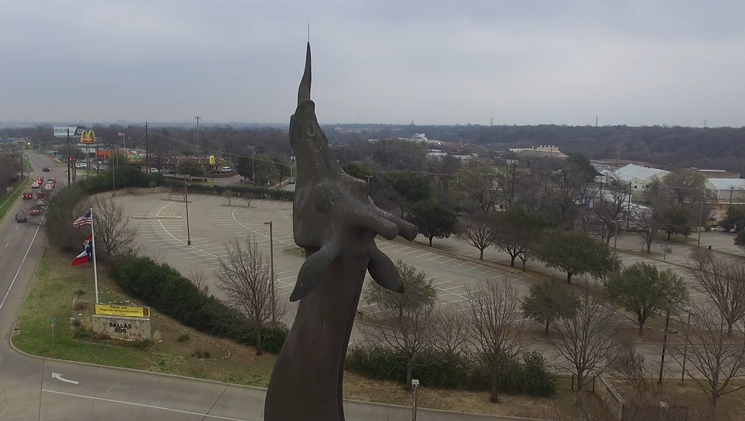

Eye to eye with the 67-foot-tall giraffe statue at the Dallas Zoo, the tallest free standing statue in Texas.

Joe Pappalardo

I’ll only have one shot at this.

Everything is legal. I have a federal license and a registered drone. I’m not within 5 miles of an airport. I have permission to capture images, and this is a public facility. Everything on the legal checklist is green. But my weather app is warning me of 20 mph gusts of wind.

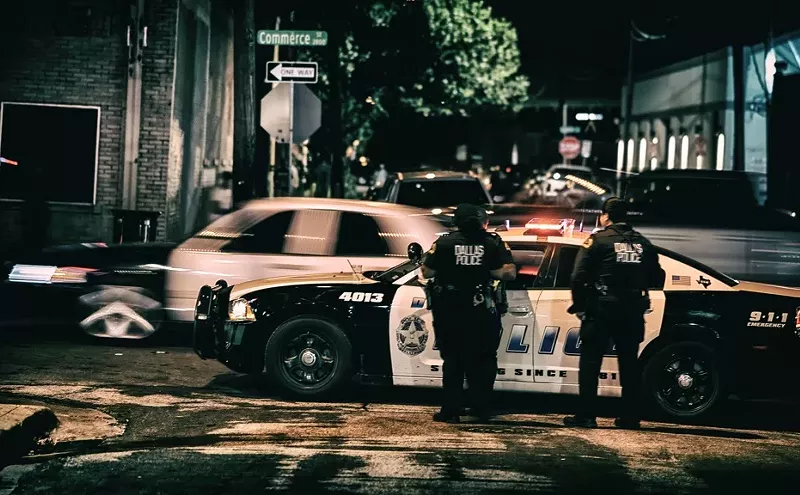

Even worse, in obsessing over the flight conditions I’ve lost track of the training. Just as I’m connecting my phone to the drone’s Wi-Fi, the SWAT team disperses and takes positions to enter the building. I hold both thumb controllers down to get Observer-1 airborne just as they spring into action and storm the building.

Being a good pilot is knowing not to cut corners. I have not learned that yet. The GPS never connected, the same mistake I made the first flight. Between the lack of station-keeping and the wind, Observer-1 didn’t so much take off as skip away, scuttling sideways like a crab across the parking lot.

You can say this about my drone: When it flies away, it manages to hit something. In this case, a parked police car. Luckily, everyone’s attention is fixed on the simulated police raid. I was able to shut down quickly and confirm that the cop car is unscratched. Two rotors, however, are broken. I pack up and slink away without saying goodbye.

In many ways, drone journalism is the last thing the profession needs. It’s the epitome of everything critics and old-school newshounds complain about: flash over substance, amateur image-taking over photojournalism, distance over intimacy.

The chief challenge is how to adapt news-gathering operations so they can make an impact — and a profit — in the chaotic digital age. Newspaper websites do what they can to stand out. Publications are torn by a number of trends that are hard to keep up with. We’re beholden to social media to distribute our content. Social media tend to prize video and strong photography. Advertisers like to chase the page views generated by stories that are on social media. The result: we're constantly looking for strong visual elements. Enter the drone.

After months of working with Observer-1, I’ve found that the drone videos we publish are not very different from any other story we run, no matter what media we use to tell it. If it’s relevant or purposeful, people will respond. If it’s just gimmick, it won’t make an impact.

I have an idea to bring the drone to capture new images of Dallas’ statues. I follow the rules, sticking to city-owned areas and keeping far away from private property. I call for permission to fly over the giraffe statue at the Dallas Zoo, buzz the Pegasus downtown and circle the towering, metal figures of Deep Ellum. I pick a soundtrack from an open source music site and let it loose on the public.

The response is tepid.

Contrast that video with another video project, one that is more meaty and less drone-focused. I get the idea while walking on what used to be Park Avenue, now part of Heritage Village. The collection of historic buildings and farm animals is nestled in what used to be City Park, in the Cedars. The neighborhood's predominant aspects now are industrial lots and homeless people.

The remaining homes on Park demonstrate the area's upscale past, but then the wide street meets a fence and beyond that, Interstate 30. The highway physically severs the Cedars from downtown Dallas.

Evelyn Montgomery, the site’s director of exhibits, collections and preservation, tells this to me while strolling the grounds with her and the resident cat. The visual from the ground is striking, but I start imaging how the story can unfold with some extra altitude. Montgomery’s game for a drone flyover and providing voice-over.

The resulting video isn’t just drone footage. The Observer’s managing editor splices in historic photos to balance the drone images. Montgomery’s voice-over provides a soundtrack. And the shot I imagined that explains how I-30 helped murder the Cedars has been realized: A slow rise from what appears as a graceful, high-end neighborhood, slowly revealed to be a stunted street, literally cut short by an intimidating moat of roads and overpasses. And in the distance, gleaming in the sunlight is downtown, tall buildings, high rents and commerce. It’s the slice of Dallas history I was hoping for, a narrative with some motion.A video without any information is as useless as a fake giraffe. People may notice it, but they won’t respond to it.

tweet this

A lot more people watched and commented on that Heritage Village video than the one about statues. It's hardly a scientific sample size, but it does prove a point. A video without any information is as useless as a fake giraffe.

Texas' unclear and unhelpful drone law is an annoyance and blunts the edge of the most serious investigative work that these tools could enable. Imagine them taking air quality samples near factories, watching drug arrests for signs of corruption or spotting locations of dog fight pits.

But there is an unintended positive result as well, in that the law keeps the focus on covering people instead of vistas. If I’m getting permission from someone, at least it guarantees I’m talking to them. That is close to what industry insiders call reporting. And more reporting always makes the view more complete, more valuable.

Observer-1 has survived my drone apprenticeship. Not everyone believed it would last this long. I asked my wife if she thought I’d embrace the aircraft as warmly as I have. “I thought you’d crash it,” she says. “And that would be it.”

Instead, the drone is on the staff and ready to fly. I invested in some carbon composite rotors, a spare battery and extra rotor guards.

I have this idea to fly along the Trinity River to trace some segments of the proposed tollway route. It might be a good idea to take a look at the area that advocates want to keep wild. It could be paradise. It could be an unremarkable floodplain worthy of a bulldozer. Either way, sounds like a story worth telling.