There was a lot more than mere irony and hypocrisy at play. The day West Dallas landlord Khraish Khraish visited me also happened to be the day after the Dallas City Council adopted a long-awaited comprehensive housing policy to address low-income housing and homelessness. Khraish told me that on the one hand, he was glad to see some kind of policy finally adopted.

“I’m really happy for the housing policy that just passed,” he said.“The underlying message here is that if you are poor and you have valuable dirt in Dallas, you cannot keep it. You gotta go. No valuable dirt in Dallas can be allotted for poor households. The city won’t allow it." — Khraish Khraish

tweet this

But his experience with the city illustrates a moral flaw that may undercut even the best formal policy.

“In Dallas,” he said, “poor families do not have the right to sit on valuable dirt.”

Once developers decide a poor area is suddenly valuable, as they did in West Dallas in 2012 after the opening of a new bridge from downtown, the city and even local media will help them push poor inhabitants out of the way, Khraish says. No new policy, he believes, will stand up to that ruthless dynamic.

Khraish had dropped in to show me maps of the major infrastructure improvements planned for the narrow sector of West Dallas where developers are building condos and shops. His point was that all of the improvements stop at a hard border where modest working-class neighborhoods begin.

By jamming new sewers, streets and water lines into the

Wall sitting on mortar.

Office of Inspector General U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

When the poor families finally sell to the adjacent developers, their property will sell for a fifth what it might have commanded had the neighborhood been included in the city’s infrastructure program just across the line. And they would have been living all those years in a better neighborhood. The way it works out, Khraish believes, is no accident.

“The underlying message here is that if you are poor and you have valuable dirt in Dallas, you cannot keep it. You gotta go. No valuable dirt in Dallas can be allotted for poor households. The city won’t allow it.

“They stopped allowing it in West Dallas, and that’s why they came after me, full tilt with an entire media campaign, not just to attack my company but me personally.”

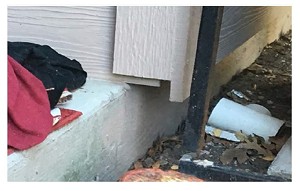

Wall suspended in midair.

Office of Inspector General U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

He has declined to sell to the major new developers crowding into the area, in part because he wants to develop his remaining land himself. Khraish recently launched a private-sector affordable housing program aimed at police and firefighters.

The city spent two years and untold resources trying to force Khraish to sell. His properties had so few building code violations that the city was thrown out of court when it tried to seize his land.

Later, Mayor Mike Rawlings called him and gave him the name of a developer to whom he wanted Khraish to sell. Meanwhile, the City Attorney’s Office helped reporters do stories portraying him as a monster whose tenants were being eaten alive by rats.

I told you here in February about a story by former WFAA-TV investigative reporter Brett Shipp telling the tale of a Khraish tenant who supposedly awoke one morning to find a rat had been nibbling on his toes. Projected behind Shipp on TV, a giant photograph of the man’s blackened toes alternated with giant photos of the rat and of Khraish.

Khraish invested a lot of money and time in a counter-investigation of that story. He was able later to prove in sworn court testimony that the supposed rat-bite guy, a person who did go to the hospital a lot, was never once treated for a rat bite. He had diabetic toes, however, which later had to be amputated. And the rat in Shipp’s photo came from a pet store.

Construction rubble left behind by contractor.

Office of Inspector General U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development

So, back to mere irony and even a few bitter laughs. Sitting in my office, Khraish and I had what I could almost describe as a good time looking at photographs in the investigative report. The pictures show how the city does it.

The report released yesterday was only the first installment in a series of investigations by the Office of Inspector General in the U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. Almost two years ago, HUD got worried when Dallas' auditor published a report saying the city was unable to account for tens of millions of dollars in HUD grant money spent on various housing programs.

Still in the works but not addressed by Thursday's report are findings by HUD investigators of questionable practices among nonprofit community housing groups, called CHODOs in City Hall slang. Sources close to the inspector general investigation, speaking to me on condition of anonymity because a public announcement has not yet been made, tell me that investigators are seeking approval from Washington and from HUD regional headquarters to look more deeply into the Dallas CHODOs.

Thursday's report was based on a narrow sample of 13 houses rebuilt by the city with HUD money under a HUD program called HOME. The investigative report found that the city misspent $1.3 million demolishing and rebuilding 13 badly bungled houses for poor families.

According to the report, the city failed to follow environmental regulations, didn’t check out contractors to make sure they were competent or credit-worthy, didn’t check up on the contractors to make sure they were doing the work, didn’t check to make sure subcontractors were even allowed to do federal government work, didn’t sign some loan documents and didn’t check the credit of homeowners given reconstruction loans.“It’s easy money. Who’s really checking? So why even perform the work if no one is checking?” — Khraish Khraish

tweet this

The report said the city failed to do all these things because the city employees running the program hadn’t been told to do them and didn’t know how anyway. The city also wrongly claimed $2.9 million in federal matching money for other HOME projects that didn’t meet federal requirements.

Khraish and I just looked at the pictures. After all, the city spent two years showing a judge photos of Khraish-owned homes where the big problems often turned out to be trash tossed in yards by tenants next to otherwise basically sound structures. But when it’s the city building the houses, the defects range from the merely infuriating to the truly hair-raising.

In one instance, the condensation overflow pipe from an attic air conditioning unit is tacked halfway down a back wall, then allowed to splatter onto a patio that is tilted back into the house. Thus, the water from the air conditioner floods the house. That’s small potatoes.

In another instance, the entire outer brick walls of a house sit not on concrete beams but on layers of mere mortar right on the dirt. In other words, the house is held up by mortar — good until the mortar gets wet.

The scariest one, Khraish and I agreed, is the photograph of a wall of a house supported by … nothing. Air. The frame of the house was built bigger than the foundation. Therefore, one exterior wall of the house sticks out over the foundation, basically hanging in midair, held up by the nails that tack the wall to perpendicular walls at the corners. It’s as good as the nails are.

The financing of these deals works like this: The city makes a loan to the homeowner for the work. But the city retains a power of attorney allowing it to sign checks to the contractor, whether the homeowner thinks the work has been done properly or not. The loans are all “forgivable.” They don’t have to be paid back anyway. The money comes from Washington.

“It’s easy money,” Khraish said. “And here’s the thing. Who’s really checking? So why even perform the work if no one is checking?”

All of the abuses cited in the HUD report predate the arrival of the new city manager, T.C. Broadnax, and his top staff and of the new city attorney, Larry Casto. Both Broadnax and Casto give every indication they intend to clean house and run a tighter ship.

But one still can’t help being struck by the contrast between the city’s attack on Khraish before Broadnax and Casto arrived, and what is revealed in the HUD report about City Hall itself at the time. If nothing else, the report reveals a stark and utter lack of commitment on the part of City Hall to provide quality housing for poor people.

Khraish told me, “I daresay that I ran my business much better, much more honestly, much more above-board than the city did during the same time. They attacked me simply for financial gain. Whose financial gain, I’m not sure exactly.

“This sort of stuff doesn’t happen unless it’s about money. This was not a moral crusade. This was a financial crusade.”

And there lies the real question. Has City Hall’s behavior been a reflection merely of its internal values, or was it acting on and fulfilling the values of the community? And if it’s the latter case, what new policy is ever going to change any of that?