WARNING: Americans have a Fear of Music; they close their ears to unfamiliar sounds and avert their eyes from reading unpronounceable names. So be prepared as you read on, my fellow Americans.

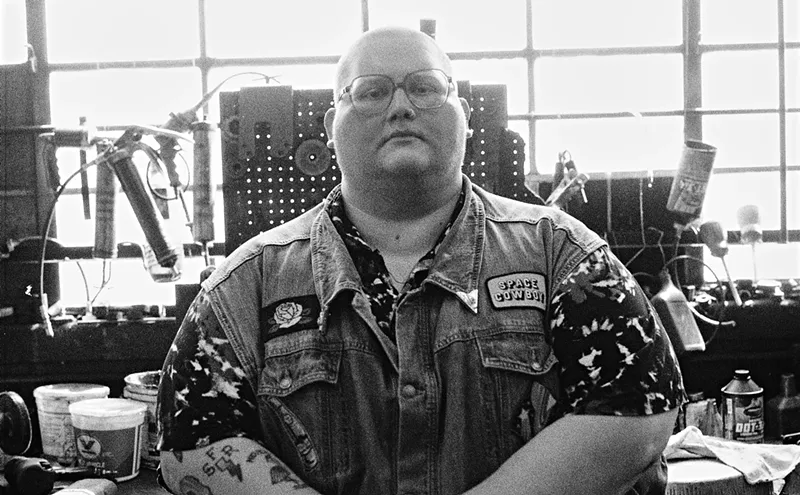

Musical provocateur Mark Rubin leads the most heroic life of any musician I know in Texas. He's a "Gentleman Musicianer and Sorry Entertainer," to put it mildly. And being at the front line of the Klezmer revival is but one of the many roads he travels.

A Stillwater, Oklahoma-born, cowboy-hatted Hebrew, he performs in Germany by "hospitality of the return ticket." Playing for 20,000 Poles in Krakow during the Festival of Jewish Culture, Rubin observed: "One well-placed RPG round and a fairly large chunk of the modern Jewish music scene would be history. Just thinking out loud, mind you."

It is a great testament to the culture of Europe that such crowds appear for non-commercial music. Rubin's hometown, Austin, is no longer where a professional plies his trade. The Live Music Capital of the World, he says, has become the Live Rehearsal Capital: "If you see me onstage in my own hometown," explains Rubin, "then you are looking at someone practicing for a gig somewhere else."

Like Yiddish, the mystical, 1,000-year-old street language of our forefathers, Klezmer's survival defies all in the modern world. Personally, I haven't yet connected with the klezmorim; to me, Jewish music is simply American—Irving Berlin, the Gershwins, Leiber & Stoller, the Brill Building, R&B, even The Great American Songbook written for Sinatra. Rubin, however, is a core member of The Other Europeans, an affiliation of master Roma and Klezmer musicians performing this summer at festivals in Vienna, Krakow and Wiemar. They're frequent stomping grounds for Rubin, who valiantly transports his 300-plus pounds along with the two largest instruments this side of a Steinway—a standup bass and a tuba—to make opening curtain.

The 42-year-old former bass player of Dallas' defunct Killbilly and Austin's Bad Livers, Rubin considers Klezmer a "vulgar" catch-all term. To him, it designates the vast secular heritage of Yiddish dance music.

"It hocks my chanuck," he says, "and speaks to my personal motivations for working in Jewish music—rather than making a living wage playing something people actually pay for."

To quote Yiddish clarinetist Dave Tarras (1897-1989): "A Klezmer is a no-talent bum who could scrape out a note or two on a fiddle and fool the unsophisticated clients that he was an actual musician."

If you've heard of any current Klezmer groups, chances are they're watered-down Vegas acts or two-bit bar-mitzvah bands. Practitioners of "fakelore," says Rubin, in the way Doc Watson described the early '60s folk revival as a "folk scare." Beginning in the 1970s, Klezmer revival bands have mixed instrumentals, folk and theater songs into a clumsy patchwork and called it Klezmer—simply because they were too scared to call it Jewish. If you want authenticity, look toward the early 20th century recordings of Abe Schwartz, Harry Kandel, Dave Tarras and the Bobriker Kapelye. All mean motherfuckers. Or check out Hungarian Tanzhaus musicianers Tamás Gombai, Sándor D. Tóth, Zsolt KŸrtsi, or Alex Kontorovich's ad hoc Goldenshteyn Bessarabian Brass Band.

Are you still reading?

"All my teachers simply called themselves 'muzikant' and their music 'Yiddish,'" says Rubin. "They're dead now. That's why I don't like to use the 'K' word. "

Nonetheless, Rubin still does Klez camp seminars around the globe. He's on YouTube with Hungary's greatest dance band bassist, Csaba Novak, team-teaching bass clinics at Klezmer Summer Weimar. Upright bass players who slap the strings are more prone to muscular injuries, like carpel tunnel. Tendon stretching is essential to avoid becoming a knurled, pretzel-handed casualty on the disabled list. Or so warns Rubin's instructional video, Slap Bass: The Ungentle Art, with fellow Austin bassist Kevin Smith, of High Noon.

No surprise then, that he describes himself as "fat 'n' fit." He's one of those rare gentlemen whose portliness becomes them. Sometimes, he even looks a little like Paul McCartney. "The morbidly obese have an extra set of hurdles in the music business," he observes. "Besides shortening our life spans and effectively restricting the range of touring abilities, there's the public obsession with everything pretty."

There's also the public hatred of things that are different. Rubin's birth father, Army Lieutenant Colonel Robert Rubin, led an all-black engineering battalion. In the 1950s, Jewish officers were not assigned to lead "whites." In Oklahoma, where he would raise Mark, he was denied admission to the local fraternal orders and country clubs. Oklahoma was not Texas. The notorious blood libel, Protocols of the Elders of Zion, was available free of charge at the barbershop. Swastikas were painted on the family home's door, and the odd brick flew through the family windows, emblazoned "Juden Gerauch"—unusually astute old-world slander for the likes of Stillwater. Rough translation: Jewish stench.

So Rubin made a beeline for Dallas when he came of age. And then Austin, where he would eventually create or join a multitude of musically adventurous ensembles, like Rubinchik's Orkestyr (old-world spelling), Mark Rubin and his Jews of the Golden West, the Ridgetop Syncopators ("My Goyische stage act," he says, of the seven-piece Western Swing outfit), Alice Spencer and her Monkey Butlers, Fatman and Little Boy (The Atomic Duo), and released his seminal album, Hill Country Hannukah.

A typical year has him veering between Frank London's Yiddish Carnival in Brooklyn, playing with bluegrass Klezmer Andy Statman at Lincoln Center, performing at L.A.'s Joshua Nelson's Kosher Gospel review, and also at the "Jewish" stage at the Montreal Jazz Fest, the Calgary and Winnepeg Folk Festivals. But there's more, of course: rolling down the streets of New Orleans with his tuba in the Panorama Brass Band; joining the Knights of Babylon or the Krewe of Morpheus during Mardi Gras; reuniting with the Bad Livers at bluegrass festivals like the Pickathon near Portland, Oregon, and the Hardly Strictly Bluegrass Festival in San Francisco; singing Czech polkas at the Kolach Festival in Caldwell; and playing Polish dances each year at the Wiesczonskis' anniversary party in Tomball. I most recently saw him in a Mariachi band at Walburg's Bavarian Biergarten, in Walburg, Texas. ("The best German cuisine in the world," he insists. You tend to trust a man of Mark's stature.)

"There's a maxim among the jazz musicians I work with in New York City when deciding if they'll take a gig or not," says Rubin. "They call it the Gig Triangle. On any date offered you have three major factors: the quality of the music being made, the amount of money being paid and then what we call the hang—best described as the joy one has with being around one's friends. The theory is that you got to have at least two factors in the positive to do any gig."

Nevertheless, Rubin's primary drive is revisiting the countries of his ancestors' persecution. His great-grandfather left the Russian shtetle of Bobriusk for the slums of West Chicago in 1897. Ain't nothin' like that old-time, Old-World anti-sem. He confronts its ghosts head-on. In Poland, he encounters Ukranian Cossack street musicians seemingly from another century. He tips them a handful of Zlotys, imagining they'll spare him before the next pogrom. Shopping in the old city center of Krakow, he spots hundreds of little carved figurines of the traditional Polish depiction of a Jew: a hook-nosed Hassid counting gold. The Poles, for their part, simply explain that it's a symbol of good luck and abundance.

Rubin envisions himself in his senior years founding "America towns" across neighborhoods in Europe, akin to Chinatowns in the United States.

By that time, the vanished Americana of juke joints, diners, neon signs, and drive-in theaters should be complete. As a matter of fact, we could use some "America towns" right now, in the States.

And American Muzikant, Mark Rubin, is just the man to bring it back.