She was slender 10 months ago when the business about evicting began. The worry since then has taken another 20 pounds from her bird-thin frame. She thinks now at least she may have a place to live until she dies, whatever shape it’s in, but when the people using her as a pawn get done playing, you have to wonder how much time Pearlie Mae Brown will have left anyway.

Is there a villain? If you want to choose one from the many excellent candidates for villain — an original cause of the misery in Brown's life and the lives of hundreds other poor West Dallas citizens — step off her porch with me. Walk out into the middle of the frayed, little, uncurbed lane in front of her house, turn and gaze due north.

Two blocks away, half-real in a gauzy haze of construction dust, an immense brown cliff rises straight up out of the earth. It blocks the street. It blocks the sun. The huge, half-built apartment building dwarfs tiny tumbledown houses at its feet and soars above the tree line. It lies straight across Crossman Avenue, making an arrogant dead end of it.

This vast new building is only one corner of a gigantic, high-end apartment and mixed-use development soaring up from the soil. Land here was dirt cheap from before World War II until five years ago.

In 2012, as soon as a new bridge designed by Spanish architect Santiago Calatrava linked West Dallas to downtown, the early stages of gentrification began. The first big projects held themselves tight against the foot of the bridge as if huddled there for shelter, afraid to venture deeper into a place where people were poor and not white. That’s over. Now the big new developments are popping up everywhere.

West Dallas always suffered some of the social dysfunction that besets all poor places, but it probably never was the scary ghetto white people assumed. Mainly it was stable, hardscrabble but churchy, family and clan centered, a place where people could walk from little houses they could afford to manufacturing jobs that kept ever-so-humble roofs over their heads.

“My father, he worked over there where they put all them apartments,” Brown says, nodding toward the mountain at the end of the street. “That used to be Austin Bridge Company," which is now Austin Industries.

“He worked there for some years. I don’t know how many years. He was working there when I was small, and after I got grown he was still working there," she says. "My mother, she did home health care.

“I was born in West Dallas, about a block from here, at 1020 Muncie Ave. I went to Fred Douglass Elementary over there on Bayonne. And then to C.F. Carr school.”

When the developers started moving west from the bridge, gobbling up whole neighborhoods, the Dallas City Council decided nobody in Dallas should have to live in squalid, substandard housing, and some Dallas housing has always been truly squalid.

Brown’s description is matter of fact. She explains why she moved to her house on Crossman in 2003 from a house she was renting a few blocks away:

“My other house fell in over there on Bayonne,” she says. “I was renting from Wheeler Real Estate then. I told them that my house was caving in, and they never would send nobody down there. I could lay in my bed and look straight up and see the sky.”

She and a friend wedged 2-by-4-inch lumber across the tops of the walls.

“That was what was holding my ceiling up," Brown says. "And that was dangerous with my grandbabies there. I had all my grandbabies there. I think it was about three of them. There was about three families living with me.”

Wheeler Real Estate, which owned roughly 1,000 houses in West Dallas and southern Dallas, is out of business now. It was infamous in its day.

Khraish Khraish of HMK Ltd. purchased the Wheeler portfolio of properties in West Dallas.

Mark Graham

A new landlord

In 2003, Brown moved to her current address, a rental house owned by HMK Ltd. That same year, HMK purchased the entire Wheeler portfolio. Along with titles to 1,000 houses, HMK took on $1 million in unpaid fines, back taxes and liens.HMK, owned by Lebanese immigrant Hanna Khraish, 83, is now run by his son, Khraish Khraish, 40. The younger Khraish says his company paid off all of the encumbrances on the Wheeler properties and spent another $4 million bringing the properties up to the existing building codes.

Critics say conditions have remained poor in HMK properties. Khraish denies that. As proof that he has operated within the law, Khraish cites the tiny number of judgments against his company over the years for violation of city building codes.

Khraish makes an additional point: His rents, in the $300- to $500-a-month range for freestanding, single-family homes, are the lowest in the city. The implicit question is how nice a house can be and still rent for $450 a month.

If a house were put into better condition, made bigger and equipped with better appliances than the HMK houses in West Dallas, could HMK or any other private for-profit company offer that improved house for a rent that the city’s poorest residents could afford? How nice can a poor person’s house be and still be a poor person’s house?

Another stark reality and important factor is the absence of alternative low-cost housing in Dallas and the City Council’s stubborn refusal to make low-rent housing available. Even people who have been granted federal rent vouchers in Dallas can use them only in the toughest neighborhoods because landlords in the rest of the city refuse to accept them.

Last year, the council voted down a proposed ban on discrimination against voucher holders — a measure that housing advocates said would have been an efficient way to help the working poor find decent housing. Every year, thousands of people who have been granted vouchers have to surrender them back to the Dallas Housing Authority because they are unable to find landlords who will accept them.

At the same time the City Council declined to ban discrimination against voucher holders, it also passed a much tougher code of standards for rental properties, requiring landlords to provide better air conditioning, better insulation, better utilities and better all-around building quality. As part of the new ordinance, called Chapter 27, the new law also imposed draconian penalties on landlords who failed to comply — as much as $1,000 per day for each property that failed to meet the new code. So for HMK, the theoretical legal exposure was as much as $1 million a day.

Khraish has said repeatedly that at least 340 of the little houses his father bought in West Dallas when he acquired the Wheeler portfolio are incapable of being brought into compliance with Chapter 27. The position of the city has been that the law is the law. Khraish either gets them up to the new code, or the city smashes him with fines.

But Khraish had another asset up his sleeve: The brilliant strategic and legal services of Dallas lawyer John Carney have been a major factor in Kraish’s successful war against City Hall.

Carney determined early on that, in his opinion, the City Council had passed a bungled law. The state law under which the Dallas ordinance was created and to which it is subordinate does not contemplate putting a gun in the face of a landlord, commanding him to make investments he can’t recoup or be put out of business. Carney determined that state law provides landlords with an exit strategy — simply to put themselves out of business.

If a landlord announces he is taking a property off the rental market and gives his tenant notice to vacate, which is not the same thing as eviction and does not harm the tenant’s credit history, then all fines against that property are stayed for six months, Carney found. During that time, the landlord must either bring the property up to code or bulldoze it.

And right there, at precisely that seam in the fabric of time, is where Pearlie Mae Brown began losing weight.

Khraish outmaneuvers the mayor

Khraish’s initial position was that Brown and more than 300 other tenants were out of luck and out of their homes at that point anyway.He could not afford to leave those houses on the rental market one day after Jan. 1, 2017, when Chapter 27 went into effect. If he did, he risked ruinous fines that could smash his company in weeks. And no matter what he did with the property — scraped it, held it vacant or redeveloped it — there would be no more $300- to $500-a-month rents when he was done. So Brown, like hundreds of other HMK tenants, received a notice to vacate.

At that point, Mayor Mike Rawlings sent up a roar of anger. The denouement of the West Dallas story, as Rawlings and the city attorney’s office clearly saw it, was supposed to be that Khraish, squeezed by Chapter 27, would sell his property to a developer. He wasn’t supposed to be able to clear it, hold it and redevelop it himself.

Rawlings accused Khraish of evicting his tenants as an act of revenge against the city for passing a tougher building code and as a way for Khraish to get out of bringing his properties up to code. He accused Khraish of thinking his land was worth more than it was.

WFAA-TV (Channel 8) and The Dallas Morning News eagerly picked up the mayor's cry. All three voices — the mayor, the TV station and the newspaper — repeatedly called Khraish a slumlord.

The city joined a lawsuit against Khraish. As part of a consent order, Khraish agreed to leave his tenants in place for a time while the city suspended enforcement of Chapter 27, but Khraish was skeptical of the mayor’s real intent.

It did not help that, while the mayor was blasting him in public, he made repeated sidebar entreaties to Khraish to sell his portfolio to larger developers, one of whom the mayor named and whose phone number the mayor gave to Khraish. At a time when the land values under Khraish’s feet were doubling and tripling, he could not help smelling a rat in the mayor’s eagerness to act as real estate agent.

The mayor insisted his only interest was in persuading Khraish to sell his rental houses to a developer who in turn would sell them to the tenants in order to promote homeownership. Last June, Khraish and Carney called his bluff. They agreed to do what the mayor said he wanted to see happen.

Half of HMK’s threatened West Dallas tenants had already found other housing by then. HMK announced it would sell its remaining properties to the current tenants and would finance the deals itself. Knowing that several tenant rights groups would pore over the sale contracts looking for tricks, HMK went to lengths to make sure the titles were bona fide and bulletproof, with a couple of conditions.

If a purchaser decided to sell within a set period of time, HMK retained a right of first refusal, meaning it had a chance to meet and beat anyone else’s offer. That was a way to prevent the property from being flipped immediately to the big developers. The other condition was that the houses were sold as is.

So let’s take a skeptical look at this. HMK was still collecting its monthly money on the houses, only now instead of rent, the money came in mortgage payments. Meanwhile, Khraish and Carney had deftly offshored the code exposure from HMK to the occupants, who were solely responsible for the upkeep of the houses they now owned.

What was City Hall to do? It was one thing to ride in hell bent for leather and cracking the whip on the kind of person the daily paper and a big TV station called a slumlord. But was City Hall really going to use Chapter 27 to put 100 or more working poor families in the street because they couldn’t afford good enough air conditioning?

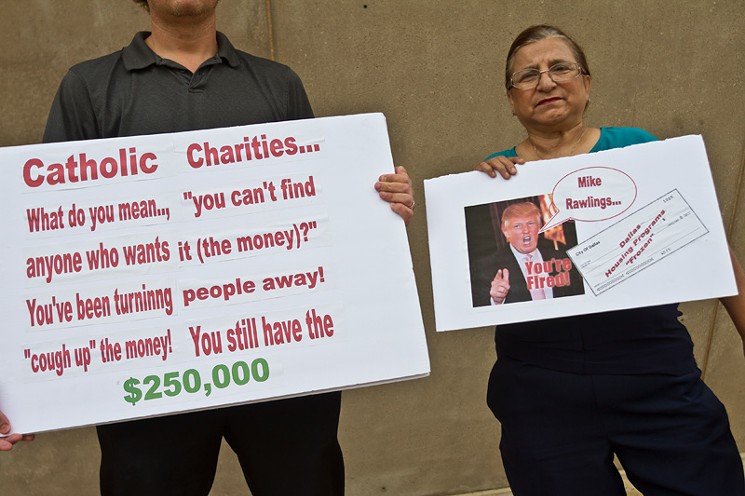

LULAC members protest outside City Hall, demanding to know why Catholic Charities of Dallas has not disbursed money from a $300,000 city grant to help West Dallas homeowners with repairs.

Mark Graham

Khraish also launched a personal political campaign to win the faith and support of grassroots neighborhood groups in West Dallas. In front of every community group he could get himself invited to, Khraish argued he was the one keeping people in their homes. He was the one offering to build low-income housing. He was the one trying to keep the community together. He characterized the mayor’s efforts as designed to sweep poor people out of their homes in favor of the big, gentrifying developers.

The community believed Khraish, not the mayor. An array of community groups quickly took his side against the mayor. At its 2017 national convention in San Antonio, the League of United Latin American Citizens, one of the oldest and most powerful Latino political associations in America, gave Khraish a rare national recognition for his work in preserving low-income housing in West Dallas. It was a stunning coup.

But much more painful to the city’s old-guard elite, Khraish backed an insurgent City Council candidate, Omar Narvaez, against incumbent Monica Alonzo, who had always been a safe vote for the mayor and the old guard on every issue. Against all odds and defying most predictions, Narvaez won, permanently weakening the mayor’s hand at City Hall and strengthening Khraish’s.

A house — but no help

During these 10 months of political warfare, Brown sat on the front porch of her cottage worrying about what would happen to her if the dice fell the wrong way. She was among four elderly Khraish tenants who, because of age and extremely low income, did not qualify for the mortgages he was offering.“Baby, I didn’t have nowhere to go,” she tells me from the porch. Motioning to a weed-choked lot across the street, she says, “I probably would have had to make up a tent across over there. I’d be like them homeless people. My son got a great big tent. About five people can get in it. I probably would have had to put it out there somewhere until I got a real place.

“I get my deceased husband’s check every month from Social Security. And then I get SSI. That’s for being disabled. I’m taking 15 different kinds of medicines. I had got my back hurt real bad in my spinal column. I should be getting more. I don’t get but $185 a month. And then his check is $575.”

Carney and Khraish came up with a way for the four who did not qualify for conventional mortgages to stay in their homes as owners, using a convention in the law called a life estate, a distant cousin of the reverse mortgage. The new owners make monthly payments based on actuarial tables predicting how long they will live. At their deaths, their houses revert to HMK. Brown, who had been paying $430 a month in rent to HMK, now pays $330 a month to stay in the house until she dies.

The unknown for her, however, is still code compliance. The house comes close to complying, but a bad floor and some other small defects in the interior mean that it does not meet Chapter 27.

At one point earlier this year, the mayor persuaded the city to give Catholic Charities of Dallas a grant of $300,000. It was intended, he said, to help people stay in their homes in West Dallas, more evidence of his desire to promote homeownership. The city’s housing department also announced out of the blue that it had found $1 million it didn’t know it had that could be used to help the new West Dallas homeowners repair their homes.“Baby, I didn’t have nowhere to go,” says Pearlie Mae Brown.

tweet this

Khraish and Carney say they are not aware of any of that money flowing to their former tenants to bring their houses up to code. Instead, they say, the money has been used to help people move out of West Dallas.

Ronnie Mestas, chairman of the Los Altos Neighborhood Association, a retiree from the Navy after 20 years service, volunteered to carry out the repairs necessary to bring Brown’s house up to code if Catholic Charities would pay for the materials. Mestas told me that Rigo Aguilar of Catholic Charities told him to bring him a list of prices, which he did. The amount was approximately $2,000. The work consisted of carpentry to repair a floor and some tile work.

“We had a meeting,” Mestas told me. “He started asking other questions he hadn’t asked before, if I was licensed to do plumbing and electrical and stuff like that. I said, ‘No, sir, I don’t do things like that.’” After that meeting, Mestas said, Aguilar did not pay for the materials.

In the meantime, Brown’s daughter Pearline, 54, met with officials at City Hall. She said that Raquel Favela, recently appointed by new City Manager T.C. Broadnax as chief of economic development and neighborhood services, told her that the city was unwilling to commit money to the repair of any houses sold by Khraish to his tenants for fear that Khraish might benefit.

“She said they’re trying to figure out a way to put a lien on a house, for how long and for whom it should go against,” Pearline Brown told me. “They were saying they didn’t want to fix up houses for the time the people are in the house because Khraish is the one that’s going to benefit.”

She told me Favela also told her it was a mistake for her mother to have accepted a house from Khraish. “She said, ‘It’s a shame she accepted one of these houses.’”

I asked Favela by email if she had told Pearline Brown it was a shame her mother had accepted a house from Khraish. In a 300-word response to that question, Favela did not say whether she had made the remark that Pearline Brown had quoted to me. As part of that longer response, Favela said, “I explained to her that the City does not have a role in a private transaction between a buyer and a seller.” She said the city is not attempting to put liens on houses that have received grant money from Catholic Charities.

I called Rigo Aguilar of Catholic Charities and asked him why he had not written the check for materials that Mestas had presented to him at Aguilar’s request. He said he could not speak to me, and he asked me to call his superiors. I asked Dave Woodyard, CEO of Catholic Charities, by email why the check had not been written. He responded that he thought it had all been taken care of.

As of this writing, nothing has been taken care of. Pearlie Mae Brown is still rocking on her porch all day, every day, worrying about her house, craning her head to gaze toward that brown mountain at the end of the street, as if at any moment the mountain may gape open and from it a shiny new truck from Lowe’s will emerge, bearing the long-awaited flooring and tile.