Newton grew up nearby, and as a boy, he swam in the public pool at the park. Later, as an adult, he jogged its trails. Even in his thirties, he sometimes met his friends there for football games, to toss a baseball or to throw a Frisbee. He’d attended concerts at the park. It was his neighborhood.

Around 11:30 that night, he stepped out of an English pub called the Mucky Duck with a sandwich and a couple of beers in his stomach. He was wearing a slick getup, a blue pinstripe suit and tie. The walk home was less than five blocks, so he decided against hailing a taxi. He hadn’t walked far down dimly lit Hall Street when he noticed a young skinhead walking his way. “Where are you going?” the skinhead asked.

Newton later guessed the man was in his early or mid-twenties. Not responding, he kept his head down and continued on his way. But when he looked back over his shoulder a few moments later, he saw a swarm of skinheads running along the hill, barreling directly toward him. “N****r, where are you going?” someone shouted. “What are you doing on our park? We’re going to kill you.”

Newton tore off down the street, and the boys chased him. Worried they would follow him home, he hooked a right down Turtle Creek Drive. He looked back once more. Between 12 and 15 people were pursuing him. Although he didn’t yet know the skinheads belonged to a small but unruly neo-Nazi gang known as the Confederate Hammerskins, he knew he was in danger. “I knew what could happen if they caught me,” he later told a courtroom.

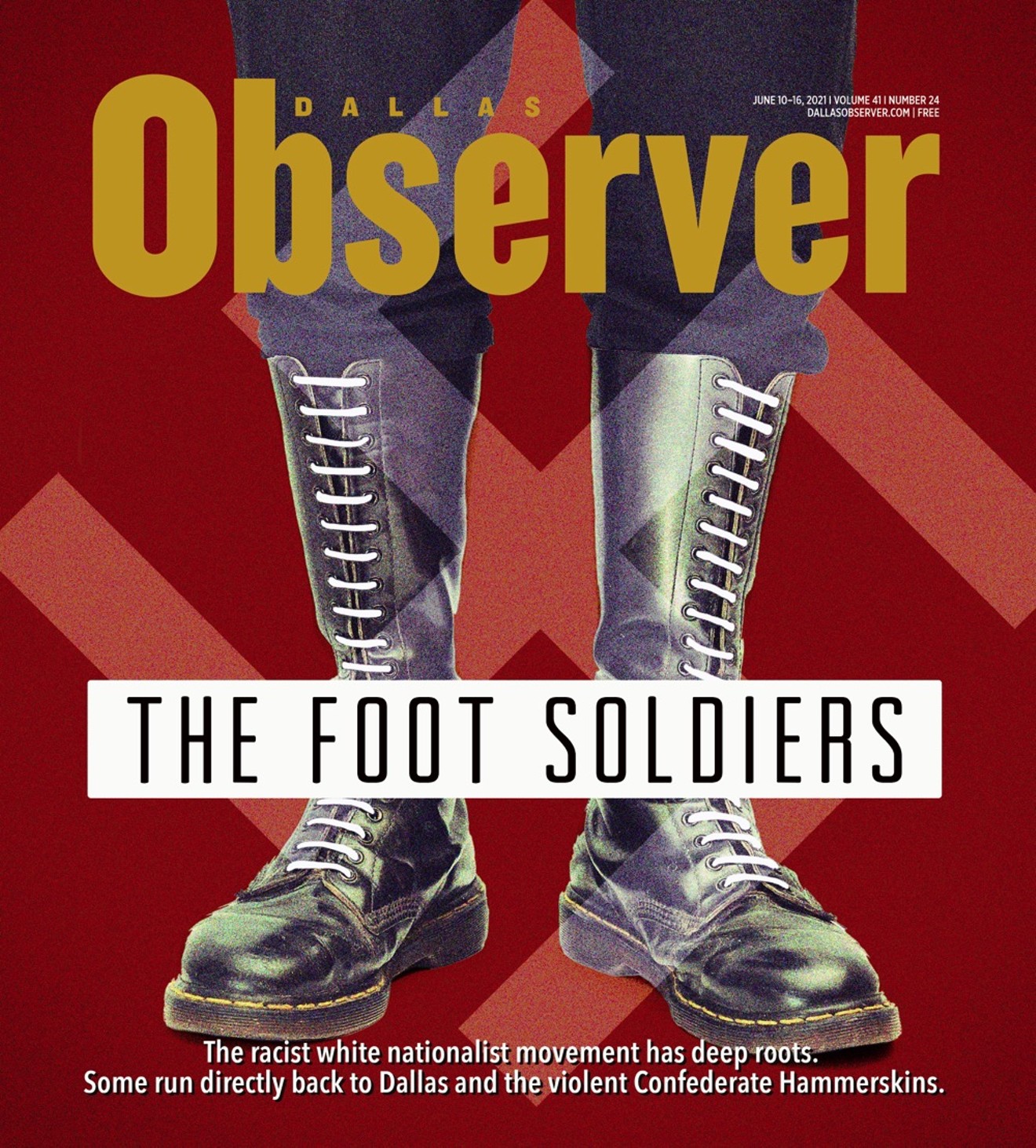

In the late 1980s, skinhead gangs fanned out around the country. Inspired by the legions of white nationalists who came before them, the neo-Nazi groups beefed up their ranks by recruiting the young and the angry. They plucked teens from the punk scene and turned them into street soldiers. The skinheads handed out pamphlets warning of supposedly powerful Jewish cabals and nefarious racial minorities. They vandalized synagogues and Jewish-owned businesses. Many groups rented post office boxes and mailed each other propaganda and letters across the nation, not unlike the way neo-Nazis and white nationalists communicate online or in messaging apps today.

That night in Dallas, the skinheads tailed Newton to Cedar Springs Road. He kept running even when they stopped. He sprinted down McKinney Avenue and ducked into Joe Miller’s, a popular local bar. He phoned the police. An officer took his report over the phone, but no one was dispatched to take an in-person statement.

By the end of the year, the U.S. Department of Justice would come down hard on the Confederate Hammerskins. The skinheads would stand accused of more than 40 crimes in the Dallas area. Later still, five leading Hammerskins would face federal felony charges for civil rights violations. Their conviction in 1990 would become an omen for skinhead gangs from California to New York.

The rest of that summer, Newton avoided the area where he’d narrowly escaped the skinheads. Each time his mother left for the bank or the store, he made sure she knew not to get near the park. “Don’t ever go through there again,” he warned her.

Born thousands of miles away in London’s working-class haunts, the skinhead scene had multiracial roots. Early skinheads promoted working-class solidarity and drew cultural inspiration from Jamaican rude boys and, to a lesser extent, African American soul music, but a new strand of far-right, nationalist boneheads eventually muscled their way in.

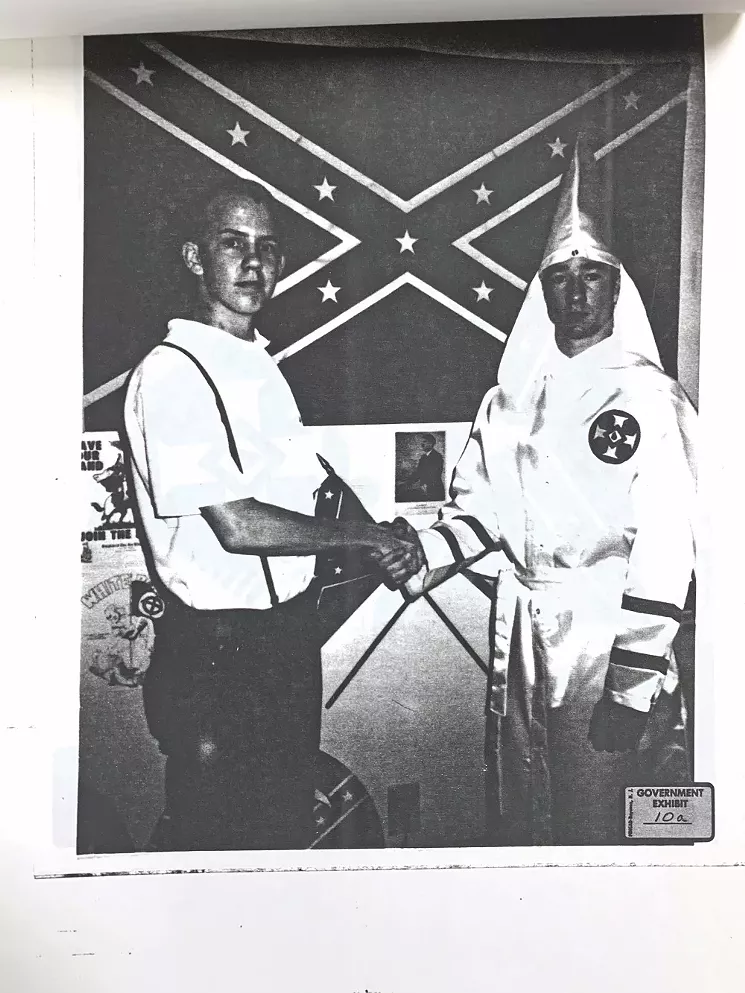

In the United States, the skinhead movement found fertile soil among neo-Nazis. What started as a hodgepodge of small, independent skinhead groups quickly metastasized into a nationwide epidemic. In an October 1988 report, the Anti-Defamation League (ADL) warned that skinheads had started showing up to “virtually every hate movement rally, march and conference over the last six months.” The watchdog estimated that the number of skinheads had swelled from around 1,000 to 2,000, spreading from 12 states to at least 21. More frightening still, the newborn movement forged ties with an older guard of white supremacists: the Ku Klux Klan, Aryan Nations and White Aryan Resistance.

It wasn’t just the number of people joining skinhead groups that worried community leaders. It was how readily the skinheads spilled blood. The skinheads beat, battered and bloodied anyone they perceived as an enemy: people of color, Jews, LGBTQ people and nonracist skins.

In two separate attacks one night in July 1988, three neo-Nazi skinheads in Laguna Beach, California, nearly beat to death two gay men with a 2-inch-thick lead pipe. That November, a Portland-based skinhead group called East Side Pride stomped Ethiopian immigrant Mulugeta Seraw with steel-toe boots and beat him with a Louisville Slugger baseball bat, killing him. A month later, three skinheads in Reno, Nevada, rolled down a street searching for a Black man. They opened fire with a rifle, killing 27-year-old Tony Montgomery.

Today, former Confederate Hammerskins are hard to find. Those who are still alive don’t speak to journalists. Some changed their names and disappeared on paper. Most don't return calls or emails. Others passed away, as have many of their victims. I tracked down a onetime Hammerskin who had testified against his former comrades. He was running a ranch in the Northwest. When I asked if he’d be willing to speak about that period of his life, he said simply: “Absolutely not.”

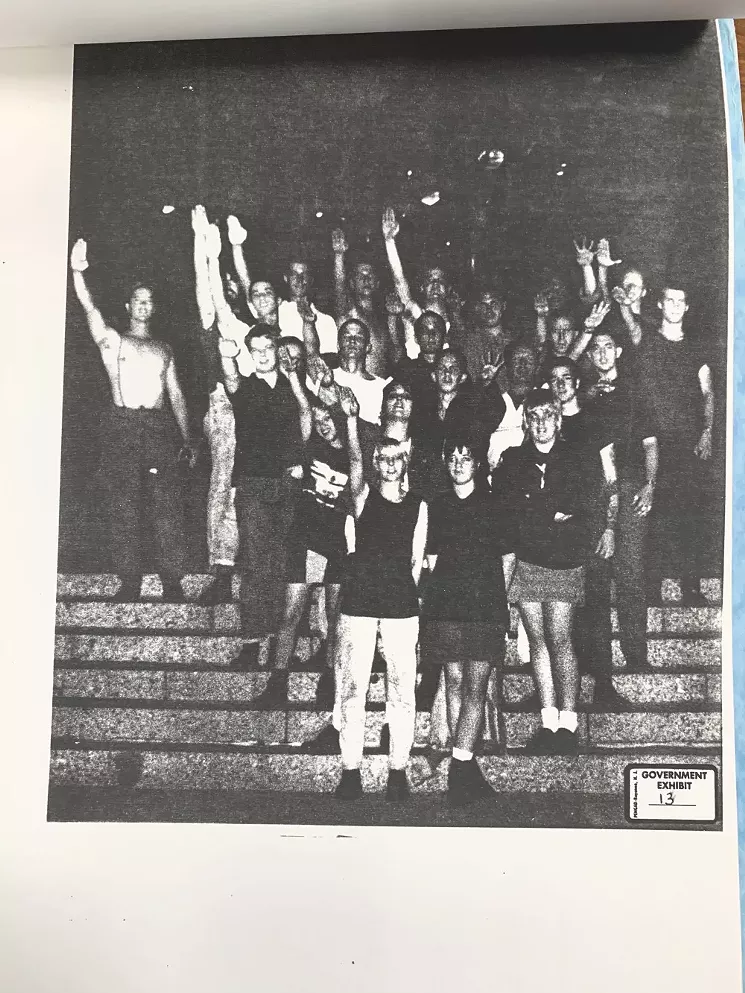

Years after I started my hunt for the Hammerskins, one image from court records sticks with me. Entered into evidence during their trial is a grainy, black-and-white snapshot taken around the time they chased Alexis Newton out of Lee Park. Around two dozen skinheads, only four or five girls among them, are posed in front of "Robert E. Lee on Traveller," the Confederate monument that once stood tall in the park. Most of them are smiling. All but one or two have their arms raised in a Nazi salute.

It’s unclear when exactly a group of Dallas-area neo-Nazis founded the Confederate Hammerskins. Some accounts put the date in late 1987, others early the next year, but by mid-1988, the gang was making headlines.

As an emblem, they adopted two crisscrossing claw hammers cribbed from a fictional fascist outfit in the 1982 film Pink Floyd – The Wall. They wore Hammerskin patches and attacked people who wore patches of rival crews. If their tempers were high or someone crossed them, they threw what they called a “boot party,” when they stomped an opponent under their combat boots.

Looking at what they saw as evidence of the nation’s decay — interracial marriage, rising crime, a growing drug epidemic — skinheads around the country fashioned themselves as a vanguard for the white working class. They read the literature, everything from the words of Adolf Hitler to American white nationalist William Luther Pierce III. In Dallas, the Confederate Hammerskins formally claimed to be leaderless, but former members say Sean Christian Tarrant called the shots.

Sometime in summer 1988, Tarrant moved into a modest home at 817 Nash St. in Garland. The Dallas suburb was home to an increasingly diverse community of some 180,000 people. There was already a sizable Black population, and a growing number of immigrants and refugees were moving to town. Strip malls housed Ethiopian churches, Chinese supermarkets and restaurants that catered to a newly arrived population of Vietnamese refugees.

At the Nash House, diversity was the main threat.

The house quickly became the group’s de facto headquarters. Tacked on the walls were Confederate flags, photos of Hitler and racist flyers. Local skins and fellow travelers from out of town came to hang out. They held meetings and hatched schemes, drank beer and performed Nazi salutes. Oftentimes, they recited an infamous white nationalist slogan known as the 14 words: “We must secure the existence of our race and a future for white children.”

In fall 1988, freelance reporter Rod Davis interviewed Tarrant while on assignment for Texas Monthly. He met Tarrant in Dallas County Jail’s Lew Sterrett Justice Center facility, where the skinhead leader was locked up on a robbery charge. “Sean is small and slight, wired tight like a tough mountain hillbilly,” Davis wrote in his February 1989 article.

Tarrant went by the nom de guerre Hellbent. Nicknames aside, skinheads who frequented the Nash House noticed he was deeply religious. He worked loading and unloading trucks at a Walmart in Garland, according to Davis. Meanwhile, Tarrant’s girlfriend was pregnant with his child, and his adopted brother was jailed in Milwaukee over an incident in which he and another skinhead opened fired on a carful of young Black men and injured a 17-year-old passenger.

That summer, Republican President Ronald Reagan was inching toward the end of his second term in the White House. Eight years earlier, Reagan’s rise to the Oval Office had taken place alongside a sharp nationwide surge in Klan activity. (In 1979, while Jimmy Carter was still president, the Klan marched in downtown Dallas.) Reagan repudiated the KKK’s endorsement of his presidency, but no one could deny hate groups were mushrooming during his tenure. Skinheads, neo-Nazis and other radical far-right groups forged ties with the Klan and its offshoots, which then operated paramilitary cells and hosted camps where their leaders instructed their robed acolytes in guerilla warfare.

In Dallas, any hate monger could easily find a news item to exploit. In 1988, the city celebrated the David W. Carter High School football team’s state championship in the 5A division. At a mostly African American school, the players had outmatched the racism thrown their way. Yet overshadowing the historic win was a crime spree of 21 armed robberies committed by 10 of the players, a headline that fit snugly into conservative America’s widespread panic over crime in city centers nationwide.

Meanwhile, across Dallas, home foreclosures had skyrocketed 30-fold over the previous four years. Starting around 1985, the crack epidemic ravaged the city, hitting Black neighborhoods the hardest. In 1988, the crime rate hit the highest level on record. Bankruptcies had doubled since 1984. Unemployment rose to 7.4 percent. Property values plummeted.

Back at the Nash House, Tarrant rallied his comrades. The way they saw it, the situation was dire. They wanted to lead by example, and the language they chose was expressed by the fist.

Around Dallas, the Confederate Hammerskins covered lampposts and alleyway walls with hand-drawn flyers. One had a small swastika hovering beneath a skull and crossbones, the words “N*****s Beware” printed on it. Another showed a Jewish man in a yarmulke fixed between crosshairs: “Reach out and touch someone — Aryan Resistance,” it read. Yet another depicted a tattooed, flag-wielding skinhead standing on a Black man’s chest. Next to the Black man was a syringe and a large knife. Many of the flyers included a P.O. box address that was shared by the Knights of the Ku Klux Klan at the time.

One especially longwinded flyer promoted Confederate Hammerskins as “working class Aryan youth.” It said the group opposed the “capitalist and communist scum who are working to destroy our once proud nation.” It claimed the “parasitic Jews (who control the mass media) are at the center of our problem” along with “the traitors of our own race who willingly do the Jews bidding. We are white warriors. Join our fight to save our white heritage before it is lost forever.”

Around that time, parents in Waco opened their mailboxes to find a letter from the Confederate Hammerskins. The note warned that drugs, gangs and anti-Christian morals had polluted white schoolchildren. Parents who wanted to know more were encouraged to reach out for additional information about “what we are doing to help the White schoolchildren of America.”

In June 1988, four Confederate Hammerskins traveled to Catoosa, Oklahoma, a small town located some four and a half hours north of Dallas. Catoosa was home to only a few thousand people, but for four days that summer, the town filled up with skinheads. Hundreds made the trip to attend Aryan Fest, which the Southern Poverty Law Center billed as the “first major hate rock festival in the U.S.”

White power bands like Tulsa’s Midtown Boot Boys played under the summer sun, a large Nazi flag draped on the stage behind them. In the audience, shirtless skinheads played tug of war and burned American and Israeli flags. At one point, hate movement leader Tom Metzger, who founded White Aryan Resistance, took the stage and issued marching orders. He told the young skinheads to return to their communities and become “the backbone and foot soldiers for the movement,” former Hammerskin named Gordon Buchanan later testified.

Back in Dallas, the skinheads readied themselves for war.

Gordon Buchanan had first learned of the Confederate Hammerskins in spring 1988. He lived in Fort Worth. He often fought with his parents and dropped out of high school in the 10th grade. He became a regular at punk shows in Deep Ellum and moved out of his parents’ house.

Buchanan was young, but he already had an impressive resume in the white nationalist movement. He joined the KKK’s Waco chapter before he turned 18 in what was apparently a rare exception made just for him. While still living with his parents, he took in a friend named Richard Brunson, who had founded the short-lived, mid-cities skinhead gang known as the American Front. That group collapsed when police picked up Brunson on an outstanding warrant from New Mexico.

The punk scene was growing in Dallas, and bands came from all over the country and the world to perform in Deep Ellum. Plenty of anti-racist skinheads were in the scene, but Buchanan later testified that both his friendship with Brunson and his time in punk crowds had led him to becoming a skinhead.

Buchanan shaved his head and dressed the part: jeans, T-shirts and combat boots. After he saw the Hammerskins on the news one night, he decided to write to Sean Tarrant. In May 1988, Tarrant and Buchanan met at a Dallas apartment off Skillman, where Tarrant was staying. Tarrant complained about all that was wrong with society, Buchanan testified. He cited the Bible to rail against mixed-race relationships, saying that “if white females sleep with beasts then they both shall be doomed and their blood shall be shed.”

“Basically that is all the friends I had,” Buchanan later told prosecutor Barry Kowalski.

“Is it fair to say that the Confederate Hammerskins became your whole life?” Kowalski asked.

“Yes, it is.”

But everything changed after Aryan Fest. The skinheads prepared to escalate their activities. Flyers wouldn’t be enough. The weekly meetings, Buchanan said, became “just very more aggressive.”

When the Hammerskins returned from Aryan Fest in Oklahoma, some members began claiming that the nation’s foremost civil rights group, the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), wanted the city to change Lee Park’s name. They agreed action had to be taken.

Arthur Fleming, who had joined the NAACP in 1980, served as the Dallas chapter’s president in the late 1980s. Decades later, in 2015, he led the group’s efforts to have Confederate names removed from schools, Confederate monuments to come down and parks to change their names.

But in 1988, he told me, there was no campaign to change Lee Park’s name or have the statue taken down. He chalked the skinheads’ belief up to conspiracy theories. “They knew we were against that stuff,” he said. “There was a lot of transition at that time. There was a lot of skinhead activity then, and we did get a lot of hate calls and bomb threats.”

Named today after Turtle Creek, the park stretches across 14 acres. In 1909, the city founded it as Oak Lawn Park, but in 1936, Dallas gave the park a Confederate makeover. On June 12, 1936, the city hosted an elaborate ribbon-cutting ceremony with American, Confederate and Texan flags. Confederate Civil War veterans, prominent local politicians and President Franklin D. Roosevelt all showed up. In attendance were Robert E. Lee’s great-grandson and D.W. Griffith, whose 1915 film The Birth of a Nation had emboldened a new generation of cross-burning Klansmen across the South.

Before the celebration ended, Roosevelt unveiled "Robert E. Lee on Traveller," a 14-foot tall statue depicting the Confederacy’s foremost leader on his horse. Speaking to the crowd, the president praised Lee as “one of the greatest American Christians and one of our greatest American gentlemen.”

Five decades later, the Confederate Hammerskins started patrolling the park. Sometimes the skinheads beat their prey with baseball bats. Other times, they would chase people they assumed were gay. On one occasion, between 20 and 25 skinheads found three or four “Mexican nationals,” according to court documents. The skinheads surrounded the men, stole their beer and ordered them to leave. Another night, Sean Tarrant reportedly slapped a white woman for speaking to a Latino man.

Meanwhile, more and more out-of-town visitors showed up. Coming from Chicago, Memphis and Tulsa, they joined the Confederate Hammerskins on park patrols, a former skinhead who declined to be named told me. He never formally joined the gang, but he sometimes spent the night at the Nash House. "I met folks from Tulsa and Memphis, and it felt like the understanding was Dallas was the place to go to take part in something that also built trust among participants," he explained."I met folks from Tulsa and Memphis, and it felt like the understanding was Dallas was the place to go to take part in something that also built trust among participants." - Former skinhead.

tweet this

Joining the park patrols, he added, "showed who was down."

"Maybe it was because I was young and Sean was charismatic, but it didn’t feel culty; it felt like he was the cool guy who knew more and had more experience," the former skinhead told me. "There was certainly a coolness factor to being at the Nash House and feeling included, which played into their recruiting strategy outside punk shows downtown."

Kevin Cardosi, a teenager from Tennessee, spent a week hanging out with the Dallas crew. “We were going to make sure that there were no minorities — no Blacks or Mexicans — in the park,” he later testified.

While marching around the park, they yelled at anyone whose look they didn’t like. “N****r n****er out,” they chanted. “Kill all the Jews,” they shouted. “White power,” they screamed.

One night in August 1988, a Hammerskin named Christopher Greer shouted to the others, “Here comes a n****r.” The Black man started running, but Greer chased him in the direction of the other skinheads. Once they stopped him in his tracks, Tarrant kicked the man and threw him to the ground. He eventually made it to his feet and escaped.

Aug. 9 had been a sweltering day with a high that topped 100. That night, Felix Sherrard and his girlfriend Fanny were on a stroll near the park when eight or nine skinheads started sprinting their way. A short, stocky skinhead yelled at Sherrard, “N****r, what you doing in my park?”

The couple ran so fast Fanny lost one of her shoes. They made it to a nearby apartment complex where Sherrard knew people. They burst into the courtyard and found their friends sitting by the pool. There was Sherrard’s childhood friend Alexis Charles Newton, whom the skinheads had chased away from Lee Park earlier that summer. They phoned the police and headed back to Lee Park to retrieve Fanny’s shoe. There, Sherrard gave a statement to the officers.

Not far away, Dallas police officer Donna K. Lowe had cornered a gang of skinheads who had been roaming the park, between 12 and 15 young men. She asked what they were up to. “Yeah, we’re just out here chasing n****rs,” one replied.

Lowe asked why. “This is our park,” another shot back. “It doesn’t belong to them.”

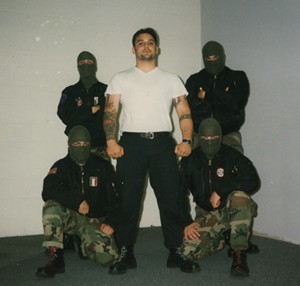

The Confederate Hammerskins were neither the first nor the last white nationalist group to recruit young people, spread their ideology and carry out violence. But the Dallas crew worked hard at what they did. Members traveled around the country and met other skinheads from Memphis to Milwaukee, and even Toronto, the ADL said in a report at the time. The Hammerskins forged ties with like-minded groups in Arizona, Oklahoma, Wisconsin and beyond.

Meanwhile, the movement made headlines around the country. “Neo-Nazi Activity Is Arising Among U.S. Youth,” a New York Times headline warned in June 1988. “Neo-Nazi youths with shaved heads are joining forces with the Ku Klux Klan and other racist groups in an alliance that could rejuvenate the struggling white supremacy movement, a report released today by the Anti-Defamation League of B'nai B'rith says,” another Times article observed that October.

Later that year, in November, Geraldo Rivera invited John Metzger, Tom Metzger’s 20-year-old son, and a pair of skinheads on his talk show. Also in attendance was a white man whom skinheads had attacked and civil rights advocates to challenge Metzger and his crew. During the discussion, Metzger called a Black guest, Roy Innis, an “Uncle Tom.” Tempers soared, chairs and punches flew. Someone busted Rivera’s nose. Ratings skyrocketed, but lost in the chaos was a worrisome fact: Tom Metzger and his skinheads had broadcasted their views to an audience larger than they could have ever dreamed of.

Skinhead activity was spiking around the country, namely in cities like Chicago, Portland and San Francisco, according to Christian Picciolini. Back in Dallas, the Confederate Hammerskins had turned the city into an especially “violent hub,” he explained. At the time, Piccioloni belonged to Chicago Area Skinheads (CASH). Although he later parted ways with the scene and became an anti-racist advocate, Piccioloni was neck-deep as a teenager in the late 1980s.

Sometime in 1988, Picciolini said, he and other Chicago crew members met the Confederate Hammerskins when several of the Texans traveled to Naperville, Illinois, to meet with more than two dozen skinheads from around the country. The attendees wore combat boots and swastika armbands, Picciolini recalled. As they sat around drinking beer, an especially drunk Texan pitched a novel idea: Skinhead crews nationwide should all adopt the Hammerskin name and unite under that banner.

“I knew many of the Confederate Hammerskins very well,” Picciolini told me. “They were trying to get everybody to come under this new umbrella called the Hammerskin Nation or being a Hammerskin.”“They were trying to get everybody to come under this new umbrella called the Hammerskin Nation or being a Hammerskin.” - Christian Picciolini, former skinhead

tweet this

Picciolini said “Chicago and Dallas were very tight,” but CASH leader Clark Martell rejected the offer. “Chicago was the group that said no … because we were the first. There was kind of an ego thing involved, but everybody else jumped onboard.”

In June 1989, a judge in Illinois sentenced Martell to 11 years in prison after he was convicted of home invasion, aggravated assault and robbery. Along with six others, Martell had barged into the home of a 21-year-old woman, stomped on her face and finger painted a swastika on the wall with her blood. With Martell in lockup, Picciolini climbed the ranks and eventually took over CASH.

The Hammerskin brand was spreading across the country, cropping up from the West Coast to the Midwest. Years later, in 1994, Picciolini received a phone call from a Texas correctional facility. It was Sean Tarrant, who was now the gang’s national director. He wanted to know if Picciolini would accept the regional director role of the Hammerskin Nation’s northeastern chapter. He accepted the role.

But early on in summer 1988 — “88, the summer of hate,” Picciolini called it — the Dallas skinheads were still busy making history. Their wanton violence had earned them a reputation around town. In Deep Ellum, some regulars, locals and anti-racist skinheads avoided the Confederate Hammerskins. Others confronted them, such as the Dumb Skater Boys, an ad hoc collective of skateboarders who brawled with Hammerskins in the streets. In other cases, individual locals pushed back against the skinheads, such as one man who pulled a gun out on them later that year and made them remove their patches.

Mark Haslett remembered those days well. Today, he works at a radio station, but he became a regular in the Dallas punk scene in the late 1980s, not long after he graduated from high school in Arlington. Haslett never had a run-in with the Hammerskins, but he heard rumors from time to time, that the skinheads had attacked someone at a show, for example.

Local punks knew racist skinheads by their tattoos and clothes, he said. “We knew enough about the different clothing rules that we could pretty reliably differentiate between a racist and an anti-racist skin,” he recalled. American and Confederate flag patches were a dead giveaway, as were combat boots and flight jackets. “Racists wore white shoelaces, red laces meant you were a leftist, and black was more neutral or just meant you didn’t want to share your politics,” he added.

After months of mounting tensions, it all boiled over on July 7. An English punk band called the U.K. Subs was scheduled to play a show at the Honest Place, a popular club on Commerce Street, but the gig was canceled because of rumors skinheads planned to crash the show.

It wasn’t the owner Greg Winslow's first run-in with the Confederate Hammerskins, but he ran out of patience that night. All summer long, the skinheads had harassed people outside clubs in Deep Ellum. That night, the club owner kicked out the Hammerskins when they showed up around 10 p.m.

A little after midnight, a white van carrying a dozen Confederate Hammerskins skidded up to the curb outside Honest Place. They hopped out, confronted an independent skinhead and demanded that he take off his boots and hand them over. Police reports and newspaper articles from the time offer a fuzzy timeline of what happened next, but when the independent skinhead refused, the Hammerskins beat him."We don’t deny that we’re violent at times." - Amy Mecum, former skinhead.

tweet this

One of the independent skinheads outside the club was Tom White, who caught a flurry of blows to the face. His lip was busted, his nose bloodied. A Confederate Hammerskin clocked him in the left eye, knocking him unconscious. Another independent skinhead, named in police reports as Charley Ball, turned his head just in time for a fist to smash into it. The punches rolled, and four or five of Ball’s front teeth chipped. Ball broke free and ran, but the Hammerskins chased him.

That’s when gunshots rang out. Winslow was in front of the club with a .22-caliber rifle. He unloaded nine shots at the van. While helping a comrade into the van, Amy Mecum, a 19-year-old Hammerskin, took a bullet in her back. The skinheads drove the injured woman to Baylor University Medical Center, but a witness had identified them and police officers came to the hospital. Nine Hammerskins received disorderly conduct citations and three went to jail.

The club owner was taken to jail, too, and charged with aggravated assault with a deadly weapon, though that was later dropped. Dallas Morning News reporter Al Brumley tracked down Mecum in the hospital, where she was wounded but in stable condition. She denied the version of events put forward by the club owner and the witnesses. “That’s bull,” she told Brumley. “That’s his point of view and not ours. We don’t deny that we’re violent at times. But because other skinheads are violent, people approach us with an attitude, so we have to stand up for ourselves sometimes.”

As the summer of hate faded to fall, the Dallas crew upped the ante. According to court records, the skinheads tried to pump poisonous gas into a synagogue in Dallas, hurled a Molotov cocktail at a church in Rosser and continued to battle in the streets.

On Oct. 8, a gale of skinhead violence swept across town. It was brisk, the sun not yet up, when Dallas police officers responded to a call at Temple Shalom. They found fresh graffiti on the walls. “Jews are the anti-Christ,” one tag read. “Jews lie,” said another. Spray painted in red, a more chilling piece of graffiti was written in broken German, a reference to a white nationalist terror group known as The Order: “Salvation for the Silent Brotherhood.”

Then there were the shell casings. The police officers found six next to the synagogue’s entrance. The assailants had shot at the windows in the door and the classroom, possibly with a .25-calliber automatic pistol, the police report speculated. Altogether, the damage topped a thousand dollars.

That same night, the skinheads damaged the Islamic Association of North Texas mosque in Richardson, not far from the Nash House. The somewhat puzzling graffiti they wrote on the side of the mosque read: "Yahweh, our white God.""He did say the vandalism was stupid, that it was just a waste of time because it just gives the Jew sympathy and it doesn’t do anything for the white race." - Chris Schutza, former skinhead.

tweet this

Across town, the skinheads also hit the Jewish Community Center, blasted out its windows and escaped without retrieving the shell casings. The investigators suspected the same gun used at Temple Shalom fired the bullets, and one of the “unknown assailants,” the police report noted, had left behind a fingerprint.

The violence had attracted so much negative attention that WAR’s Tom Metzger chewed out the Dallas crew and ordered them to behave like “clean-cut Aryans,” one former Hammerskin later testified. “He did say the vandalism was stupid, that it was just a waste of time because it just gives the Jew sympathy and it doesn’t do anything for the white race,” Chris Schutza told the courtroom.

The Dallas City Council ordered an emergency session on Oct. 12, 1988. Council members were asked to vote on only one item: "Resolution denouncing the recent acts of violence against religious institutions and further requesting the resources of other law enforcement agencies to assist police in their efforts to stop this violence."

They unanimously approved the resolution and committed that City Manager Charles Anderson would “take all actions necessary” to curb the skinhead violence.

The following day, an undercover task force was born and placed under the leadership of Detective Truly Holmes, a former Army drill sergeant who had tracked down serial rapists and other violent criminals during his time at the Dallas Police Department. The task force worked with federal authorities on the investigation.

A day later, police responded to another criminal mischief call. A man had attacked a car carrying a white woman and a black man in Dallas. While booking the suspect, the officers measured his height and weight, 6 feet tall, 200 hundred pounds. His name, they learned, was Daniel Alvis Wood. The police report written up noted his tattoos. “White Power” was inked on his left forearm, “KKK” on his right. The report added that due to the “numerous criminal mischief acts,” they recorded his fingerprints.

On Oct.17, 1988, Dallas PD Detective Michael Black met an undercover intelligence officer at a vacant lot near the nightclubs and show venues lining Deep Ellum’s Elm Street. The officers photographed fresh graffiti and collected beer bottles, a cup and a cardboard, six-pack carton littering the sidewalk. They took samples of the red spray paint. Could it have been from the same canister used to deface Temple Shalom? Would it definitely link the skinhead violence in Deep Ellum to the same perpetrators of the failed gas attack and anti-Semitic graffiti at the synagogues?

An analysis of the material brought back identifiable fingerprints on two Coors bottles and a Budweiser. An investigator found positive matches for fingerprints on the paper backings of stickers posted on the windows at Temple Shalom. They found a match with Daniel Alvis Wood's right index finger.

The following day, two detectives arrested Wood at his apartment on Lake Haven Drive. The bond was set at $25,000.

Less than two weeks after Wood’s arrest, Dallas police received yet another disturbance complaint, this time in Deep Ellum. Shortly after midnight on Oct. 27, undercover and dressed in plain clothes, officers Richard Morrell and Jon McKeon saw a skinhead gang posted up in front of the 500 Club’s entrance. The owner told the officers he had not given them permission to sit on the stairway and block entry to the club. They arrested one of the men, Michael Lewis Lawrence.

They had only arrested two Confederate Hammerskins so far, but the special task force was already circling the Confederate Hammerskins.

Police attention or not, the Dallas crew still had big plans. After all, there were only a few weeks left before the 50th anniversary of Kristallnacht, the “Night of Broken Glass” in 1938 when Germans rampaged and ransacked Jewish homes and businesses around the country, set ablaze synagogues and department stores and murdered Jews.

For weeks leading up to the anniversary, the Dallas crew planned to terrorize the Jewish community. Daniel Wood made a list of businesses he thought were Jewish-owned. When Nov. 9 came, the crew loaded up a pickup with Nazi flags, cans of spray paint and concrete blocks. They hashed out the logistics of smashing windows and talked about how German Nazis carried out a nationwide spell of violence. “You’re not a real Nazi if you don’t do that,” Wood told the others, according to Chris Schutza.

“We were going to smash Jewish businesses,” he added.

They didn’t get far. Shortly after they set off, police pulled them over. In the months that followed, grand juries met, suspects faced charges and one former skinhead after another agreed to testify against their friends. In March 1990, an all-white jury delivered a guilty verdict for five Hammerskins: Sean Tarrant, Jon Jordan, Daniel Alvis Wood, Christopher Greer and Michael Lawrence."Just because five people have been convicted, doesn’t mean there aren’t more radicals and bigots around." - Rabbi Kenneth Roseman, Temple Shalom.

tweet this

Officials and rights groups praised the verdict. Prosecutor Barry Kowalski told the press the outcome sent “a warning across the nation that young racists cannot commit crimes of hate,” while the ADL called it a “major victory.” But one man quoted by The Associated Press had his doubts. "Just because five people have been convicted, doesn’t mean there aren’t more radicals and bigots around," said Rabbi Kenneth Roseman of Temple Shalom.

The rabbi was right. During the trial, a group of skinheads had attacked a Black woman driving in Richardson, smashing her windshield and shouting racist slurs. One of those booked was a former Hammerskin who had testified for the prosecution during the trial.

The five Hammerskins were sentenced to between four and nine years in prison for civil rights violations, but the Hammerskin legacy didn’t go away.

A year after the trial, one night in June 1991, three skinheads — prosecutors claimed they had links to the Confederate Hammerskins — went on the hunt for a Black man in Arlington. They drove around town, drunk and listening to white power music, and eventually spotted a Black man hanging out with a few white coworkers on the bed of a truck on a quiet residential street. Before they sped off, got arrested and went to prison, they shot and killed Donald Thomas, a 32-year-old warehouse worker. (That killing prompted Texas to adopt its first state hate crimes act.) All three were eventually convicted on charges related to the killing and sent to prison.

Although the Hammerskin Nation was only a loose iteration of what the Confederate Hammerskins had started in Dallas, the brand caught on. Throughout the 1990s and well into the 2000s, Hammerskin Nation chapters cropped up around the country and in Europe. Wherever they went, violence followed. They organized white power concerts, published white nationalist literature and recruited in prisons. By 1999, the Southern Poverty Law Center estimated that Europe was home to some 2,000 Hammerskins. On its website, the ADL still describes the gang as “the most violent and best-organized neo-Nazi skinhead group in the United States.”

Nearly three decades after the Confederate Hammerskins prowled the streets of Dallas, thousands of white nationalists, neo-Nazis and far-right marchers descended on Charlottesville, Virginia, on Aug. 12, 2017. They came out to protest the city’s decision to remove a statue of Robert E. Lee, but they were met in the streets by anti-fascists, anti-racists and community members who objected to their presence in town. The young fascists fought in the streets all day, hoping to secure the statue’s future in Charlottesville. By the time it was over, a neo-Nazi plowed his Dodge Charger into a crowd of anti-racists and killed 32-year-old activist Heather Heyer.

In the months that followed, community backlash, infighting and pressure from anti-fascists helped cripple the resurgent far right. The statue is slated to come down in Charlottesville. In fact, Confederate monuments came down across the country. Schools were renamed. Confederate flags were removed from government buildings.“I live in this area. I mean, I grew up in that area." - Alexis Newton, victim of skinhead attack

tweet this

A month later and 1,200 miles away, the Dallas City Council voted 13-1 that Confederate monuments violated city policy. In October 2017, the city sent in a crew to remove "Robert E. Lee on Traveller." Police were there in case anyone came out to protest the decision, but no one showed up. In 2019, the city sold the statue to Holmes Firm PC, a Dallas law firm, for $1,435,000. Today, it stands tall on a golf course in Terlingua, not far from the U.S.-Mexico border. In April that same year, the Dallas Park Board voted to change the name of Lee Park to Turtle Creek Park.

Alexis Charles Newton never lived to see the park's name change or the statue come down. He passed away in 2004. But more than three decades ago, he told a jury how he escaped the Confederate Hammerskins one night in 1988. After he got away and ducked into Joe Miller’s bar, terror gave way to anger. What bothered him most, he told prosecutor Barry Kowalski, was the way the skinheads kept referring to the park as theirs. “I live in this area,” he said. “I mean, I grew up in that area.”

Note on sourcing: This story draws heavily from court documents, police reports and newspaper archival materials. Other sources include former skinheads. Also helpful were several books, including Christian Picciolini's White American Youth, Arno Michaelis' My Life After Hate, and historian Kathleen Belew's Bring the War Home.