The men of country music have always exuded a distinct brand of masculinity. From Bob Wills to George Strait, these are the Marlboro Men of the music world — rugged, tough and stoic. It's so ingrained that no one ever questioned the rhinestones that were popular for so much of country's history.

But after several years in which that machismo ran rampant, the men of country music are undergoing a reinvention for the better.

The emergence of artists like Sturgill Simpson, Jason Isbell and Chris Stapleton has fundamentally changed the conversation about country music. The shift is much more than one in lyrical gravitas or sonic sensibilities — these artists present a starkly different idea of what it means to be a man who makes country music.

Masculinity is the bedrock on which country music is built — an assertion true of pretty much any type of popular music — but in this style of music, a sort of dichotomy has always been at play. Two strains of masculinity have comfortably worked alongside each other to round out the sound. The rough meets the tender. The Waylon Jennings and the Conway Twitty. Sometimes the two coexist within one act, like Hank Williams Sr. or Johnny Cash.

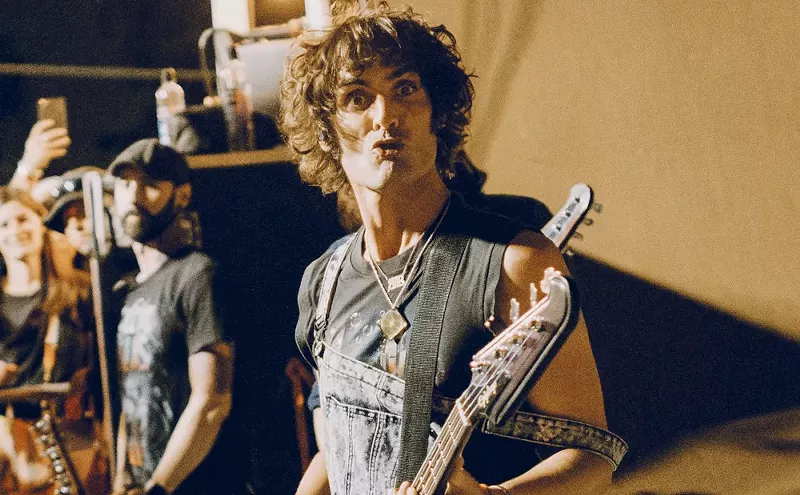

In bringing a completely new aesthetic to country music, artists like Simpson have also brought more nuanced ideas about what it means to be a man. Simpson’s 2016 release A Sailor’s Guide to Earth features a cover of Nirvana’s “In Bloom,” interpreted as a sort of tribute to the virtue of male sensitivity. Overall, Simpson’s work paints the picture of a quieter, gentler style of masculinity, one that recalls Twitty and Cash in its subtlety.

For a long time, that flew in the face of what made country music successful. Shirtless dudes — complete with glistening abs and ripped jeans — singing about scoring with chicks have effectively turned into the butt of the music world’s jokes. And those jokes have started to wear a little thin. It was almost as if there was some sort of competition to prove that the prominence of feminine country-pop — which had experienced a couple decades of incredible progress — didn't mean that anyone who still made country music was a wuss.

The appetite has now changed so rapidly that the shift can be seen on the Billboard charts. Songs like Tim McGraw’s “Humble and Kind,” a love letter to his college-aged daughters, and Thomas Rhett’s “Die A Happy Man,” written about his wife, have replaced the overtly sexist and objectifying tunes that were massive hits just one year ago. It seems unlikely that Florida-Georgia Line’s heavy-handed innuendo and jokes about female anatomy would already be replaced by tamer, more sensitive tunes, but the wants of country fans are notoriously fickle.

Maybe that’s something that has less to do with Simpson and more to do with the fact that Stapleton has become both a massive, nearly overnight success and a bellwether for what is to come in country music. Stapleton is just the latest in a line of artists bestowed the honor of “saving” country music, but surprisingly it's not mediocre songwriting or Affliction shirts that he's saving the genre from. Instead, Stapleton brings a new brand of masculinity to the genre, one that makes country music’s old reality seem woefully outdated.

Today, artists are admitting that the machismo of the past five years or so is unsustainable, like chart-topper Chase Rice who penned a letter to fans apologizing for the vapid nature of his most recent single. In the context of a song like “Fire Away,” the smoldering ballad that addresses loving someone with mental illness, Rice’s “Whisper” is obnoxiously patronizing and, not to mention, sonically outdated.

The change has been two-fold. As these artists have changed the perception of what country music is supposed to sound like, they’ve also dramatically shifted the way the men in the genre are expected to act. It’s important to remember that Luke Bryan was, once upon a time, an artist in the vein of Josh Turner, who disappeared from the charts as quickly as he'd ascended them once his charming love ballads fell out of style.

It was only after the spray-tan, backwards-cap aesthetic became profitable that he started releasing garbage like “Country Girl Shake It For Me.” Songs like “All My Friends Say” and “Rain Is a Good Thing” aren't terrible songs, but they eventually devolved into “Sorority Girl.” It wasn’t always all bad.

Bryan has also shifted away from his old work. His 2016 release Kill the Lights is markedly less sexist (less overtly sexist anyway) than his previous albums. It is this change, in the artists who were the most guilty of reinforcing hyper-masculine tropes in country music, that is most dramatic of all. It would be one thing if Stapleton was just making his own music; it’s quite another to see him actively influence other musicians. Especially those who have made millions of dollars doing the exact opposite.

Ultimately, Simpson, Isbell and Simpson are living the lineage of artists like Glen Campbell and Conway Twitty, even if the music (and the men, to be fair) couldn’t be more different. There have always been men in country music who have refused to adhere to hyper-masculine standards in the genre, but it may soon be the rule instead of the exception.

Audio By Carbonatix

[

{

"name": "GPT - Billboard - Slot Inline - Content - Labeled - No Desktop",

"component": "21721571",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "STN Player - Float - Mobile Only ",

"component": "21861991",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - 2x Rectangles Desktop, Tower on Mobile - Labeled",

"component": "22608066",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "GPT - Leaderboard to Tower - Slot Auto-select - Labeled",

"component": "17357520",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]