There is performance art. There is rock 'n' roll. And then there are St. Vincent dress rehearsals.

Everyone in the showcase room of Prospect Heights' Complete Music Studios seems to know this, because even at 4 p.m. on the last frigid Friday of January, the end of two months' worth of 12-hour, five-day-a-week rehearsals, each person (four musicians, two managers, a lighting designer, a guitar tech and a choreographer) dutifully occupies their station.

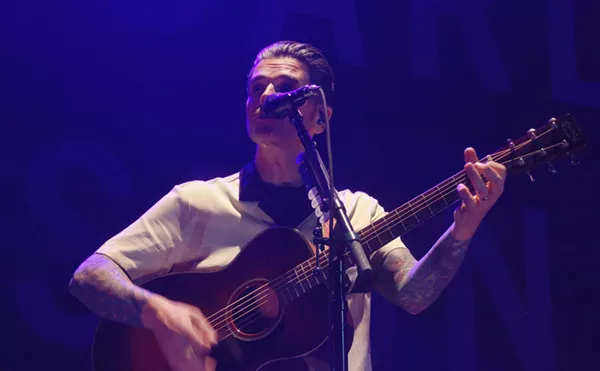

On a low platform, framed by about a dozen lighting apparatuses, St. Vincent herself, née Annie Clark, stands downstage in a glittering cocktail dress made of a gold vinyl that makes her look like a bionic Metropolis figurine, her frizzy, gray-dyed curls framing her face like an electrified storm cloud. Working her guitar up and down with her signature severity, she stares intently at the opposite wall of windows, twitching her head and limbs robotically as she and her band march through "Rattlesnake," the jittery opening track on her forthcoming fourth solo record, St. Vincent. After three songs, she thanks an invisible crowd in her soothing, singsong lilt.

Then things get weird.

"You were born in the 21st century," she intones, a priestess communicating with spirits. "The corners of your mouth turn down when you laugh. Your favorite word is ..." She pauses for comedic effect. "Molecular."

Offstage, a crew member begins reading sentences aloud. She repeats them. Clark has written this eerie stage banter in advance, and is now rehearsing lines. "You once tried to make a hot air balloon out of bedsheets. You were disappointed when it did not fly, but you did not give up." The stage bursts to life as Clark and Moog player and guitarist Toko Yasuda commence a robotic dance, skittering forward and backward at opposite intervals like wind-up androids; the lights strobe terrifyingly, turning their moves into a stop-motion play. The lights slow their flicker, and suddenly it looks like there are two Clarks, a dark and a light, fighting over her body while she bends and twangs her strings.

Once in a while, between songs, she speaks to the invisible crowd again. Another song begins, a new ballad, and Clark retreats, guitarless, to the stage centerpiece: a massive powder-pink throne made of stairs, where she lies down, brushing the ground with her fingertips as one might the surface a reflecting pool. Later, she'll return to the throne and throw herself down its steps, headfirst, in strobe-lit slow motion.

Every downbeat, every dead-silent transition, every poke battle over a theremin in this proceeding is immaculately scripted, down to Clark's explosive, Byzantine guitar solo on Strange Mercy's "Surgeon."

Reminder: This is just the rehearsal.

"It's sort of like training like a professional athlete," Clark, 31, says two days later, sitting at a table with a small glass of sparkling Italian wine. Somewhere in the world beyond, it is Super Bowl Sunday, but here in the bar of The Standard, East Village, for Annie Clark, it is the end of a bizarre press day, one in which she was asked to go about a normal day with a photographer in tow. (Did they truly want to go to the dry cleaner's with her?) She wears neutral colors and her curls are tucked neatly into a dark beanie. It's a stark contrast from the wild, supernatural Ursula coiffure that has become the iconic centerpiece of St. Vincent since its cover art was revealed in December.

"People have spent money on a ticket, and maybe that money is the equivalent of them spending a day of their life at their job, or half a day. Money is absolutely time," she says. "I feel, now, that it would be disrespectful to work out the kinks on the people who spent a day of their life making the money to buy the ticket to come and have an experience."

For Clark and everyone around her over the past few months, that experience has been everything. St. Vincent is an evolution unlike any other the guitarist has made in her seven years as St. Vincent. She's left 4AD and Beggars Group, her artistic homes since 2007, for Loma Vista, a nascent label backed by the major Republic. She's making music in the wake of a massive collaboration with David Byrne, one that produced Love This Giant, an album that involved marching bands and facial prosthetics, among other wacky experiments. With St. Vincent, Clark wields multiple new swords: a creative director in Willo Perron, the artistic mastermind behind live shows like Kanye West and Lady Gaga; a choreographer in Annie-b Parson, who orchestrated dances on the Love This Giant tour as well as Byrne's previous collaboration with Brian Eno; and, of course, a host of her own innovative guitar-masquerading tricks, twisted pedal-and-synth explorations that add wattage to anything she's made before.

"It's more confident," she says of the record. "I'm extending a hand. I want to connect with people. Strange Mercy, which is a record I'm proud of, [was] definitely a very accurate record of my life at a certain time, but it was more about self-laceration, all the sort of internal struggle. [St. Vincent] is very extroverted."

For all her onstage virtuosic flair — which existed in the form of stage dives long before she added modern dance and a giant pink throne — matching the words "extrovert" and "Annie Clark" feels a bit odd. Though she's played music for at least a decade, first as a touring member of the Polyphonic Spree and in Sufjan Stevens' band, then as a solo artist, St. Vincent has managed to craft a public image that is eloquent, thoughtful, and has virtually nothing to do with her personal life as Annie Clark. Questions from the press about her family — she grew up Catholic in Dallas as one of eight children, and has lived in the East Village for much of her career — or her friends or whom she dates are shut down or nimbly redirected toward more "interesting" conversation; rarely do St. Vincent Q&As broach topics beyond her creative process, her gear (her signature axe is a Harmony Bobkat) or her artistic pursuits. She sticks to many of the same lines of dialogue in interviews (which explains why almost every feature about St. Vincent reads the same). Small personal details are pieced together over time, of course, but unlike many artists of her caliber, she's created an anti-cult of personality, a media-savvy mystery determined to keep all eyes on the art instead of the artist.

Even behind the scenes, she remains the consummate professional, rarely exposing more to her team of collaborators than she would an interviewer on a good day. For example, when I suggest to David Byrne over email that Clark is a private person, his first response is, "Ha ha, that's an understatement."

"Despite having toured with her for almost a year, I don't think I know her much better, at least not on a personal level," he writes. "We're more relaxed and comfortable around each other, for sure. You could call it privacy, or mystery or whatever — I know a few isolated things about her upbringing, school, and her musical likes and dislikes — but it's nice that there are always surprises, too. Mystery is not a bad thing for a beautiful, talented young woman (or man) to embrace. And she does it without seeming to be standoffish or distant."

That talent for controlling her own narrative without alienating anybody has become, more or less, the crux of her essence and success as St. Vincent. In 2009, Clark told the New York Times that she likes "things that are unsettling." Every subsequent profile, it seems, has extolled her ability to straddle two distinct identities, one warm and one profoundly unknowable. Her lyrics flirt with the candid and the esoteric without committing to either; a review of Strange Mercy lauded its "emotions that are as cryptic as they are genuine and affecting." She creates a dystopia in the video for "Digital Witness," then films a how-to clip demonstrating a soccer trick she learned in grade school for Rookie, a website for teen girls.

And when you interview her, the conversation is always good — she might tell you an unrelated story about her house in college, where a dead rat on the porch once left a visiting older sister weeping for her quality of life — even if she ends up picking the topics most of the time.

"I've learned a few things," she says of her time in the public eye. "I realize this lovely conversation is artificial; [in a real conversation,] I wouldn't talk about myself this much, I just wouldn't. I also know that being too sarcastic or too self-effacing doesn't translate in the press because it's devoid of context. Sometimes journalists ask [female artists] more personal questions." (The questions asked of Clark can get as personal as how much she weighs.)

"From the beginning of her career as St. Vincent, Annie Clark has succeeded in avoiding the confessional in her music," says NPR pop critic Ann Powers. Clark is one of a select few slated to play NPR's SXSW showcase in Austin next month. "This is not easy for a female artist — women in the arts are almost always assumed to be more naturally emotive than men, and less in control of what they produce. So it's a huge accomplishment that St. Vincent [has] succeeded as a construct, and as one that still could hold emotion and deep meaning while still highlighting Clark's mastery."

"You just have to have your own boundaries about things you're willing to talk about and things you're not willing to talk about," Clark says. "Everybody has lives and heartbreaks and disappointments and great joys and all this stuff. But that's what I put into the art. There's an intimacy and a full commitment in the art that makes me feel like it could potentially do a disservice to the art. [The Beatles'] 'Martha My Dear' is about a dog. I wish I didn't know that."

The power Clark wields isn't just relegated to her art. It resonates, among the people she works with, the people who write about her and her fans. It's such a strong force that when her commitment to boundaries is questioned, the blowback from her public is immediate: When a comedian condemned Clark's refusal to discuss her love life on a recent podcast, for example, fans and journalists swiftly criticized the move as cruel and contemptuous, and within 48 hours of the podcast's going live, it had been edited and re-uploaded, sans critique; in the following episode, the comedian apologized. (The same comedian wrote a feature about the guitarist a few years ago, a story that, though she's quick to note no hard feelings, Clark says "kind of fit [me] into an agenda and [another] concept of the world, when we had sort of diametrically opposing ideas about the universe.")

"To say one of the corniest things you can say about an artist, [Clark] is a storyteller," Powers says. "I am always curious to follow where her songs go, because they go farther than most by current artists in terms of creating worlds. ... It takes the listener outside of herself, and I think that makes us less interested in Annie's personal details, too. We want to go on the trip she's charting, which is about dreaming and thinking big, not getting stuck in autobiography."

"As St. Vincent, Annie has very much done this seemingly impossible thing of getting over the women-in-rock hump by being bulletproof. It's allowed a post-gender freedom," says Rookie music editor and frequent Voice contributor Jessica Hopper. Hopper has interviewed Clark (often the subject of agape "women in rock" trend pieces) many times since 2007. "And I think, in some regards, that was her mission: not to be the exception but to be the new rule."

Everything you ever need to know about Annie Clark, the artist reckons in an email a week later from Europe, is already being sung by St. Vincent.

"There is so much autobiography contained within the songs that I don't see the need to deflate them with the mundane," she writes. "I'm not very interested in the 'behind-the-scenes' sacrifices at the altar of the god of content."

Not that there's much room in Clark's schedule for a personal life even if she did want to spill her guts. Twelve-hour practices, all-day photo shoots, days of national and international press and, presumably, sleep seemingly dominate her life. (Our two-hour conversation will be the only time we'll be able to meet.) It's been this way since at least 2011, she says, when she embarked on the Strange Mercy tour. From there, it was straight into Love This Giant and that tour; throughout that year and a half, she picked up the "experiences, images, ideas and people" that became St. Vincent and came to life in longtime producer John Congleton's studio back home in Dallas in the fall of 2013. If it were up to her — and for the most part, it is — this is how life would be all the time: consume art, make art, discuss art, perform art, repeat ad infinitum.

"I used to think, at some point, there would be one day when I would learn how to be a well-adjusted person with a home," she says. (Her New York apartment, she says, is full of "deeply uncomfortable, horrifying art" — it's the only thing she likes about it.) "But then I made peace with the fact that I'm not interested in that. I'm not excluding it for the future, but [right now] I would rather be making records."

And at the moment, with a new label, different resources, solid sales (by the end of 2011, Strange Mercy had sold more than 50,000 copies) and the potential for massive visibility (she's now been on the Colbert Report twice, and has appeared on Gossip Girl, Comedy Central's @Midnight and friend Carrie Brownstein's Portlandia), she's gearing up to be able to do that for a long time — far longer than many of her '00s indie-rock compatriots, anyway.

"To come from the world she's come from and to be able to make four albums is almost unheard of nowadays," says Adam Farrell, creative director at Loma Vista. Though now a part of her new label home, Farrell has worked with St. Vincent since her debut, formerly as vice president of creative and marketing at Beggars Group. "Annie fits perfectly with what we are trying to do as a record label. [She] is a unique talent and a vanguard across art and culture."

What's more, Farrell says, Clark understands what her success means to the people who see her succeed.

"She's inspiring to anyone, women and men both, and she knows that," he says. "My 7-year-old daughter is obsessed with her. She saw the photos we took out in L.A. and, from that point on, called her the 'rock-star lady Daddy works with.'"

"The first conversation I ever had with Annie, when I was potentially interested in becoming her agent, was the first of a series of very long phone calls that were absolutely a joy," says David "Boche" Viecelli, president of indie touring agency Billions and senior partner at Lever and Beam, Clark's management company. Boche, like Farrell, has also worked with the guitarist from the beginning. "She was so intelligent and expressive and inquisitive and everything about it just struck me as, 'This is the kind of artist I want to work with.' Now I think she's learned what to pare away as unimportant and what to emphasize as the absolute essence of what she does."

For her fourth album cycle (fifth, if you count Love This Giant) she's wielding that essence and the power that's come from boiling it down in a new way: to create a "stylized," "intentional" and "heavily referenced" experience that's far more incisive than ever before. (Don't call it her Ziggy Stardust, though; "I think it's cohesive but I wouldn't call it a concept album," she says.) Perhaps in part thanks to her work with Byrne, she's intentionally left most of her "orchestral" instrumentals behind, in favor of more angular guitar and synth distortions.

Songs like "Rattlesnake" — a naked communion with nature gone horribly awry — and "Huey Newton" — an Ambien-tripping encounter with the Black Panthers cofounder's ghost — have basis in fact. But even the most banal lines — even, for example, when she sings her to-do list, "take out the garbage, masturbate," on "Birth in Reverse" — are bathed in a science-fiction glow, an effect blown out with the help of Congleton and additional percussion by the Dap-Kings' Homer Steinweiss and Midlake's McKenzie Smith. As Clark said in her announcement of the record earlier this year, St. Vincent is "a party record you could play at a funeral," a characterization that, if multiple subsequent interviews are to be trusted, "sounds like myself."

While most of St. Vincent was masterminded alone, her art direction was born of collaboration: a partnership, negotiated by Farrell, with Willo Perron.

"The indie vernacular is always marred with this kind of unintentional, laissez-faire, I-don't-give-a-fuck [attitude]; it's just a snapshot," Perron says. "But in our conversations, we were like, 'Let's do something for that audience that's super intentional.' The performance, the look, everything thought through to minutiae. There's a story, maybe not a narrative-narrative, but an aesthetic story, a through line."

The pair exchanged a steady flow of cultural talismans and assembled a "visual bible" that has guided every artistic element of the newly reborn St. Vincent, from costumes and lighting to videos and, of course, the instantly iconic album art.

"I'm very drawn to symmetrical images, and I wanted to make sure that the cover conveyed a sense of power. That leads you down the rabbit hole of 'What does power mean? What does that translate to? What does that look like?'" Clark says. "In this instance, it seemed as though power was in intentionality. So I'm on the cover, on this pink Memphis chair that's very structured, very symmetrical, very sturdy. But also, it's pink, a soft color. I experimented with different poses; it was so interesting, every micro-movement ... if I put my legs to the left, it looked like Golden-era Hollywood. If I put my legs to the right, it looked imperious and queenly in a way that was just not it. So I think the cover shot we got, it was like the third shot [we took]. Symmetrical, clean: It was direct."

The result: an aesthetic Perron describes as "postmodern-meets-new-cult-leader," a commanding new identity that takes cues from touchstones like Alejandro Jodorowsky's shamanistic The Holy Mountain (she says she had no idea that Kanye West had picked up on the 1973 film around the same time); the angular, colorful Memphis furniture design movement of 1980s Milan; and (of course) old David Bowie YouTube clips. It's more than a few jumps from the guitarist who wailed, "I don't want to be a cheerleader no more" on her last record (and played a life-size ceramic doll in the corresponding "Cheerleader" video to boot).

The art, as rehearsal showed, doesn't disintegrate when it meets the outside air, either. With the help of lighting designer Susanne Sasic and throne architect Lauren Machen, that otherworldly aura is translated to the tour's stage design. There's little accompanying St. Vincent onstage other than Toko Yasuda, keyboardist Daniel Mintseris and drummer Matt Johnson, but despite the minimal collection, she says, "everything you hear is made by a human." That means while Mintseris is teasing horns and strings out of his keyboard, the synth tones are coming from Clark's guitar pedals; and when Clark relinquishes her instrument for a melancholy throne lament, Yasuda assumes guitar-picking duties. And of course Annie-b Parson's artfully stiff choreography — for which she mined her own past work designing routines for a fleet of guitar-strapped dancers on David Byrne and Brian Eno's elaborate 2008 tour — fills each and every moment when Clark's limbs are free of instrumental imperative (as well as many moments where they're not).

"She wanted this show to be something powerful, and at the same time, something very supernatural," says Parson, from whom Clark requested frequent notes at the ends of their long-winded rehearsals. "Maybe not the first day you teach her the movement, but the third day, she totally embodies it. She's a very natural performer, so when you give her a movement, she knows what to do with it. That's not typical of a non-dancer, not at all. She's very special."

Of course, despite all the professional high-art talk, Clark's still got a soft spot for the extemporaneous. (She's a crowd-surfing, rip-soloing Dallas-to-New York rock guitarist, after all.) For all her refined tastes, she's still using Netflix and a fourth-generation HBO Go password to binge on Scandal and True Detective. ("I love Matthew McConaughey now. He's a Texas boy. There's something comforting to me about his accent. The only thing I don't like [about the show] is that the women are only prostitutes, nagging wives or mistresses.") She and Yasuda sometimes use Louis C.K.'s Louie theme song as a vocal warm-up. And the inspiration to bleach her hair came from The ("totally insane") Bachelor: She took the plunge after watching recent contestant Sarah Herron leap off a 30-story building, despite a crushing fear of heights, to stay in the running. "She fucking did it!" Clark exclaims. "She faced her fear. The reasoning is questionable maybe, but she faced her fear, maybe for no good reason, but maybe it's admirable. She had blonde hair and I was like, I think I'm gonna go blonde. If she can [go] off a building, why not?"

Yet, true to her paradoxical nature, there's still something profound about her more pedestrian endeavors. At one point, our conversation inexplicably turns to high school sports; when I explain how water polo is played, she responds, eyes wide in amused disbelief: "We distract ourselves from death in so many creative ways."

A week after our meeting at the Standard, Clark and her band are on a very different stage. This one is in Tribeca, at design house Spring Studios, on the occasion of Diane von Furstenberg's Fashion Week show. At the back of the runway, off to the side, St. Vincent and her band occupy a small platform against a wild backdrop of black and white. It could have been the light before, but her hair — wild again — is definitely lavender at the roots now, and she's traded her gold vinyl frock for a short black wrap dress. Instead, the models are in metallics; as they begin parading looks down the platform, the band opens up and plays a few songs as accompaniment to their strut. While most eyes are on the women sashaying past, Clark performs Parson's choreography through the two or three songs that soundtrack the show, and at the end the models and von Furstenberg take their bows and dance to St. Vincent.

A few minutes after the show concludes, Clark and the band move to a larger stage in a members-only lounge, where high-threshold credit-card holders cluster to watch a live stream of the show projected on a white wall. Everyone is young and dressed as relevantly as possible; supermodel Coco Rocha is here. Now, as guests sip pink cocktails and regale each other with tales of Fashion Week shows past, St. Vincent and Co. rev up again, under deep blue and violet lights. There is no pink throne here tonight, but a small platform takes its place, and as St. Vincent moves back and forth between the edge of the stage and the back, she and her bandmates perform their robotic choreography just as methodically as they did at rehearsal.

Only now there's a spark in Clark's angular joints. Where the robotic moves were truly dead-eyed as she trained, that dance seems just slightly bigger, pumped with the kind of understated adrenaline that historically has preceded fearless leaps into crowds. Of course she doesn't jump, but as she gazes out into the sea of cocktail dresses and tailored blazers, many of whom have probably never heard of St. Vincent, her eyes flicker.