The club was packed, even though it wasn't yet finished. "We were still spray painting the ceiling and putting smoke eaters in the place," Wynne remembers. The headliner that night was an R&B singer named Al "TNT" Braggs, and once he and his band hit the stage the air conditioning went out. "We were giving away drinks, and people were drinking high balls from thirst. Everybody got so loaded, it was just insane. I never saw people drink like that," Wynne says. "It was a mess. We learned the hard way."

Soul City opened its doors 50 years ago on June 22, 1967. The venue was the brainchild of five overly optimistic men — Wynne, Stan Levenson, Jack Calmes, David Nichols and Don Safran — most of whom were still in their 20s. "We were greenhorns," admits Wynne. "We didn't know anything about what we were doing."

At the time, Deep Ellum was considered a relic, a neighborhood whose moment passed in the 1920s with Blind Lemon Jefferson. Club Dada was nearly two decades away. Arenas like American Airlines Center and Starplex were science fiction concepts, virtually impossible with the technology then available — although Calmes would play an integral role in making them possible.

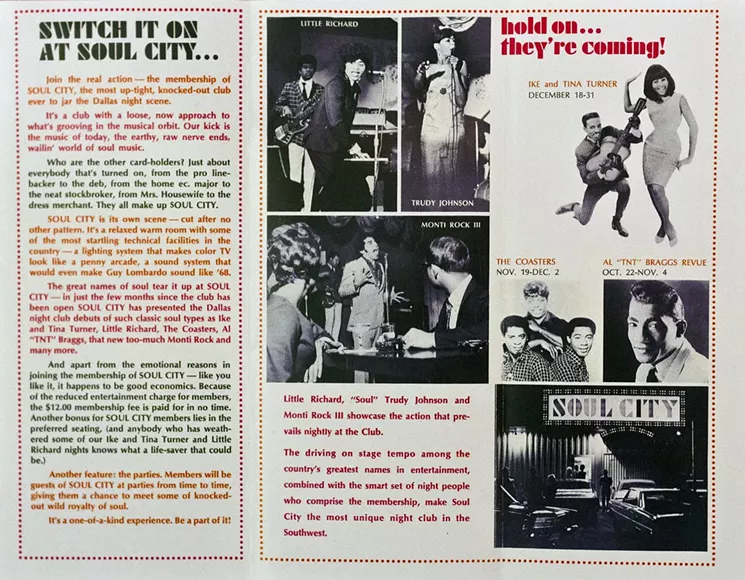

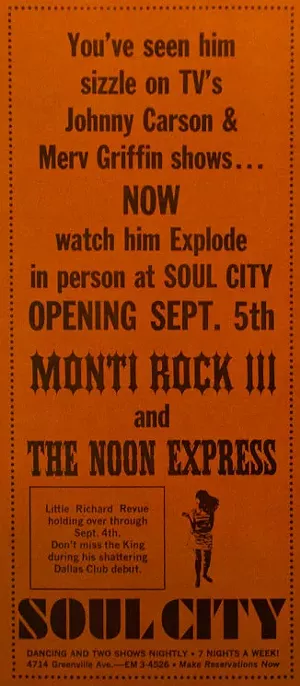

The fans who stood in line in the sweltering heat along Greenville Avenue that night were decked out in suits and ties and dresses, and they'd never seen a club quite like this one. Over the course of its brief life, less than two years, Soul City hosted a who's who of R&B A-listers and rock 'n' roll royalty, such as Ike and Tina Turner, Stevie Wonder, Jackie Wilson, Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Kenny Rogers. One-hit wonders and local musicians also took the stage.

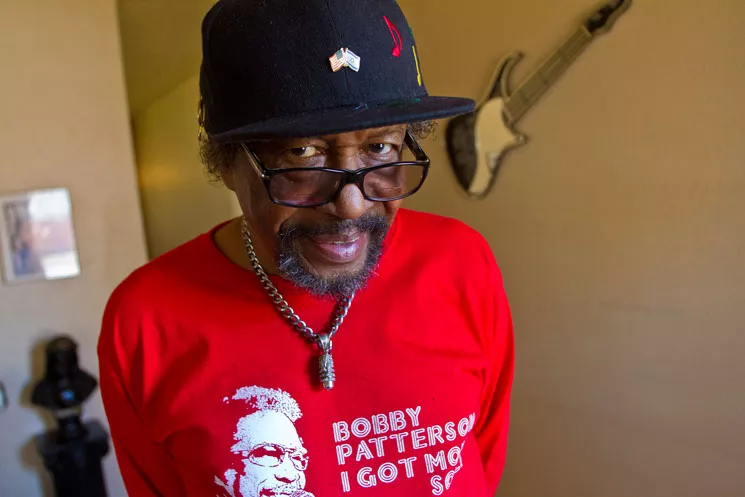

"There were lots of places to play, but Soul City was the first of its kind," says soul singer Bobby Patterson, who played the club frequently with his band, the Mustangs, while he was a student at SMU. "It was real ahead of its time, and professional. That's what made it stand out from the rest of the clubs."

Half a century later, memories of Soul City are fading, due to a lack of physical documentation and because many of those who experienced it — including three of the five business partners — have passed away. But anyone who enjoys live music in Dallas unknowingly owes the club a debt of gratitude.

The inspiration for Soul City, like so many other ideas of its kind, came from a late-night drinking session. It was early in 1967 and Angus Wynne, then a young concert promoter, was having drinks with Don Safran, the arts and entertainment editor for the Dallas Times Herald. Wynne came from a family of businessmen; his father, also named Angus, founded Six Flags Over Texas and his brother Shannon is a restaurateur.

They were in the ballroom of the Cabana Motor Hotel off Stemmons Freeway, the six-story hotel owned by Doris Day. Actress Raquel Welch once worked there as a server. "I'd never run a club, but we wanted to do something that had something to do with the big movement in R&B," Wynne says. "Don brought it all up very casually, believe me, but we got loaded and sat and batted a bunch of names around."

One of the names of the club that didn't make the cut was Blues Bag, but once the pair landed on Soul City they decided they had a winner. Safran introduced Wynne to Stan Levenson, a distributor for Dot Records, and Wynne in turn introduced Safran to his business partner, Jack Calmes. David Nichols, whose mother promoted shows, was the fifth partner.

"We went out looking for a place and found this place on Greenville," Wynne says. "It was just kind of a shell of a place, concrete floors and a bunch of tables with wooden straight-back chairs and red-and-white table cloths."

The bar, located on the corner of University Avenue, had been owned by Dallas Cowboys quarterback Don Meredith and country songwriter Ray Winkler until it went out of business. "We all got together and threw down 2,000 bucks apiece," Wynne says."There weren't a lot of places in Dallas then where you could order a mixed drink."

tweet this

By the time the Soul City plans began taking shape, Wynne had already been running shows for several years with Calmes. They met during college in the summer of 1962; Wynne attended the University of Texas and Calmes went to SMU. In 1963 they booked their first show together — Chuck Berry on the weekend of the Texas-Oklahoma football game — and in 1965 they incorporated a booking and promotions agency called Showco.

Concerts in the early '60s were almost unrecognizable from the ones of the 21st century. "There weren't touring acts like there are today," Wynne says. "This was right at the end of the [vaudeville] touring business where the road acts were variety acts and stuff like that." Concerts often took place in school auditoriums and small theaters, and bands traveled in package tours, like the one Buddy Holly, Ritchie Valens and the Big Bopper were on when they were killed in a plane crash. "There would be maybe 15 acts who all sang two or three hits and had common bands," Wynne says."Maybe they'd change the guitar player."

Some larger venues were available, including Dallas Market Hall, the Music Hall at Fair Park and, most notably, Louann's, a pre-World War II restaurant at Lovers Lane and Greenville, not far from where Soul City would open. "It was huge. It took up the whole corner," Patterson says of Louann's. "The thing was two stages inside and one stage outside — that's how huge the place was, man. Thousands and thousands of people would get in there." But it catered to a different audience, booking blues and jazz artists, and their shows were less frequent than Soul City's daily bookings.

What all of the live music venues shared in common was poor production quality. Musicians ran their own amps through underpowered PAs that were used to make announcements, and there was no front of house to mix the sound. The lighting was similarly bad.

Wynne attended an Otis Redding show around this time. "The band came out and just killed it, but you couldn't hear the vocals," he says. Between Redding's two sets, Wynne called up a friend who owned a music store, who agreed to open up shop even though it was a Sunday. "Otis and I jumped in his bus, beelined over to NorthPark Center and loaded out a bunch of stage stuff," he says. "We were a little late, and Otis was driving like a maniac, but man was [the second set] great."

With Soul City, however, the five partners saw a future — however distant it may have been at the time — where just such a scenario would no longer have to happen.

When Soul City opened its doors in the summer of '67, it was an instant hit — and not just because of the music. "It seems like every night when you'd go there, you knew nearly everybody in the crowd. It was such a popular hangout ... a see and be seen kind of thing," says Billy Bob Harris, a friend of the partners and frequent patron of the club. "I don't know how it got so popular so fast, but they had great entertainment there."

Harris, in fact, could often be counted on to help get the party started, if the need arose. "If we had a slow night, we'd call him up and say, 'Billy Bob, there's nobody here,' and before long there'd be 40 or 50 people coming through the door, and they'd all bring more people through the door," Wynne says.

Harris chuckles at the memory. "It didn't make any difference if they were weekends or weekdays," he says. "I spent a lot of time there and had a lot of fun."

One of Harris' readiest partners in crime was Dallas Cowboy Craig Morton, then the backup quarterback behind Don Meredith and later the starter for the team's first Super Bowl appearance in 1971. "Almost all my friends on the Cowboys were married, so that was a pretty tough deal to get them out there," says Morton, who knew Wynne through his uncle Bedford, one of the Cowboys' founders.

Soul City's high-end feel — "People would come in dressed to kill," according to Wynne — meant that seemingly everyone showed up at least once, no matter their age or station. Sometimes that made for a clash of cultures, like when "Treat Her Right" singer and Texas native Roy Head performed. "Nancy Hamon, Evelyn Lambert and Jane Murchison [all showed up] — millionaires' wives, all good old gals. Nothing bothered them," Wynne says."Chuck Berry was doing his little duckwalk with his guitar and he just backed right off stage."

tweet this

Head proceeded to somersault off stage and land at the feet of the three women, who sat in the front row. "He startled them half to death, but they thought it was the greatest thing they'd ever seen," Wynne says.

The good times were likely greased by the ready supply of alcohol, a feature that wasn't so easy to come by in Dallas establishments back then. Soul City was one of the city's first "private" clubs, a term that referred to the arcane liquor laws that were enforced by the Liquor Control Board, the predecessor to the Texas Alcoholic Beverage Commission. "There were two ways to do it: You either had a locker system where each customer had their own liquor in a locker in the club, and the other was to have a liquor pool where you pooled all the liquor," Wynne says.

Soul City took the latter route, meaning it was technically a private club and customers had to sign in at the door. It may not have been practical — "You had to keep two sets of books. It was the most screwy deal and it was all to satisfy the churches," Wynne says — but the more expensive license enabled them to have a full bar, rather than serving only beer and wine.

"There weren't a lot of places in Dallas then where you could order a mixed drink," says Harris, but Soul City was one of them. At other places, "You brought your own bottle and then you'd buy whatever you wanted to mix with it in the club."

One thing that the partners couldn't do anything about was the requirement that the bar close at midnight, leaving the operating window at a scant four hours per night. But the party often carried on after hours, usually back at Harris' house. "That's where I met Kenny Rogers," Harris says. He introduced himself to the Houston native, who was singing for the First Edition, one night outside the bathroom. "He said, 'What do y'all do when the clubs close here at 12?' I said, 'Well, we generally party at my house,'" Harris recalls. Rogers didn't have his own car, so Harris gave him a ride. "We became lifelong friends. I still talk to him a lot."

Every so often, Harris, who worked as a stockbroker at the time, paid the price for those late nights. "I was doing a stock market report on the radio a number of times during the day," he remembers. "One morning, I called in and [the host] said, 'Boy, your voice sounds a little different.' I said, 'Yeah, I stayed up too late last night.' He said, 'How do you know?' And I said, 'Because when the alarm went off this morning, I still had ice in my glass.'"Ike and Tina Turner had one of their many backstage fights while at Soul City — unbeknownst to the staff, until Tina appeared onstage with a bloodied lip.

tweet this

What really set Soul City apart, however, was the presentation. Equipped with tiered seating, mini cocktail tables with sleek plastic chairs, and brown shag carpeting, the layout was sparse but stylish and, as Harris puts it, "There wasn't a bad seat in there." The semi-circular stage, located in the corner of the room, had a curtain that would raise up to reveal the band, which was a novelty at the time as well. "It was the first club in Dallas that had a curtain situation, just like in Vegas," Patterson says. "That was phenomenal for back in the '60s."

Most important, the partners took great care in getting an adequate sound and lighting system in place. "It was a tight little room but we had an actual lighting director, a guy called Alex Von Saher. He was a theater guy who had colored lights," Wynne says. Space was so tight that there was no walk-up bar, only table service, and there was only one bartender. "That was before anyone had miked instruments; you didn't have to [because the rooms were so small]. But it was exquisite sound for the time and place."

Soul City's bookings leaned toward soul and R&B, but drew in a number of rock 'n' roll acts as well. Artists who were slightly past their prime but still in top form appeared, performers like Chuck Berry, Little Richard and Fats Domino. "Back then, Dallas was the premier music city [in Texas]," Patterson says. "Everybody who was somebody with a hit record came through there. It wasn't huge, but it was so nice and so comfortable."

Berry was responsible for one incident that Patterson says he and Wynne still laugh about. "Chuck was doing his little duckwalk with his guitar and he just backed right off stage," Patterson recalls, cackling. "And he just laid there. Angus went over to him and said, 'Chuck, are you all right?' And he said, 'Yeah, but I'm too embarrassed to get up.'" Wynne remembers the story differently, saying that Berry crawled back up onstage without ever missing a beat in the music.

Jerry Lee Lewis would cause a considerably bigger commotion. "The acts we'd get most of the time we'd get for several days or weeks even," Wynne says. Before the first of Lewis' appearances, a man showed up with an order of garnishment to seize Lewis' wages. Fearing that the club stood to lose out if Lewis got busted, Wynne proposed the man wait for the final night and that in the meantime he could attend the shows and drink for free. "He said, 'Man, you got a deal.' Sure enough, he was front row, center, drinking his ass off with a different girl every night," Wynne says.

Lewis' manager discovered what was happening during the final show, and ran up on stage immediately to tell Lewis. "Jerry Lee stops the show and says, 'They ain't going to pay Jerry Lee! Y'all go get your money back!' And I'm starting to lower the curtain," Wynne says.

"We were afraid bottles were going to be thrown," adds Levenson.

Ike and Tina Turner had one of their many backstage fights while at Soul City — unbeknownst to the staff, until Tina appeared onstage with a bloodied lip. (The pair would eventually split for good during a visit to Dallas in the mid-1970s.) "Tina was an absolute joy to work for," says Larry Harmon, who worked the front door. "When [the musicians] were being themselves, and not being entertainers, they were different people, really.""Most other clubs were mostly white. Soul City was different because of the acts they booked. If you wanted to see Little Richard, of course you'd have some black people come through."

tweet this

Of all the shows they saw there, Harris and Morton pick out Jackie Wilson's as their favorite — but that show nearly didn't happen. The soul singer came up missing during soundcheck, having fled for a bar after breaking up with his girlfriend. "We found him sitting sloppy drunk at one of them, bawling," Wynne says.

They brought Wilson back to the club, assuming the show would be a disaster. "The band starts up and all of a sudden he went up like a light switch. He just went on," Wynne marvels, snapping his fingers. "He delivered the most amazing set. Nothing but hits, nothing but great moves."

The majority of the acts that Soul City booked were black artists, which in turn led to a more diverse audience than most venues. Wynne says it was one of the first clubs in Dallas to not be segregated. "Most other clubs were mostly white. Every now and then you'd see a black person," Patterson says, with a laugh. "Soul City was different because of the acts they booked. If you wanted to see Little Richard, of course you'd have some black people come through." That didn't sit well with everyone: "They were jealous of us at the Cabana," Wynne says. "It got to be where the bartenders [at the Cabana] called Soul City 'Negros Nook.' They thought they were really smart, you know?" This apparently was a reference to a bar at the Cabana called Nero's Nook.

Before long, though, people were trying to copy Soul City's formula — literally, in at least one case. "One [Dallas] Cowboy opened a club over on Denton Drive called the Silver Helmet," Wynne says. "He had an architect come in and take dimensions of the room, which he took back, shrunk down to an even smaller area, and put up a strip with a marquee that was exactly like ours."

Another venue, the Losers Club, opened down the street as a would-be competitor — not that Wynne seems to have felt very threatened. "[The Losers Club owner] came in and he did steal some of our acts," Wynne acknowledges. "But by that time, we'd had them and played them several times, so they weren't getting really good offers from us anymore."

Soul City was never actually profitable. While it remained a trendsetter, by early '69 the ownership could see the writing on the wall. "The average club had a lifespan of only 18 months back then," Wynne says. "Clubs would open and close based on fads. We were another of the fads, but we had a superior product."

The music industry was changing at a rapid pace by the end of the decade, but Wynne says it was a meeting with an Atlantic Records promo man that convinced him the club's run was over. "I said, 'What's the next thing that's coming in?' He said, 'Man, you wouldn't believe it. It's this thing called heavy music,'" Wynne says. "I said, 'What's that?' He pops the trunk — there's a thousand LPs in there — and he pulls out a couple that say, 'Led Zeppelin.'"

This was one trend that Soul City wouldn't be versatile enough to adapt to.

There was life after Soul City for most of the founders. Wynne and Calmes, himself a guitarist who would sit in on sets at the club, continued booking outside shows through Showco. Calmes also married Morgan Fairchild. Levenson, who had established the Levenson Group with his wife in 1966, was doing outside consulting, eventually counting Paramount Pictures and Warner Bros. among their clients.

Wynne and Levenson would even inadvertently play a role in forming ZZ Top, when Wynne introduced Billy Mack Ham — an old friend from record distribution and ZZ Top's future manager — to Billy Gibbons during a Moving Sidewalks show booked by Showco.

Soul City eventually closed its doors early in 1969, although the exact date has been lost to time. "Peace and love started to come in. That's what sunk it eventually," Wynne says. "Nobody wanted to go to clubs anymore. They wanted to stay outside and smoke weed."

But staying outside and smoking weed was another trend that the Soul City partners had anticipated: On Labor Day weekend that year, with the help of Atlanta promoter Alex Cooley, they hosted the Dallas International Pop Festival in Lewisville. The festival — modeled after Woodstock, which had happened only two weeks prior — was everything that Soul City couldn't be, with Janis Joplin, Sly and the Family Stone, Grand Funk Railroad and, yes, Led Zeppelin on the bill. Somewhere between 120,000 and 150,000 people attended the three-day festival.

The partners even hired the same sound company, run by Bostonian Bill Hanley, that had been used at Woodstock. "They had this big huge tower of all these [speaker] cabinets with all this stuff hard-wired in. If you had something go wrong, you'd just have to cut the wire. There were so many speakers you didn't need all of them," Wynne says. Calmes and two of his friends, Rusty Brutsche and Jack Maxson, took note. "They took a look at what we paid him and said, 'We're going to go into this business.'"

Wynne, discouraged by the $100,000-plus it took to put on the festival, walked away from music to pursue real estate, but Calmes, Brutsche and Maxson — the latter two of whom were engineers — carried on with Showco. They developed a modularized cabinet system inspired by what they'd seen at the International Pop Festival, soon to be followed by a mixing board console and stage monitors. Later came video monitors and state-of-the-art, automated lighting rigs, all of which completely revolutionized live music and opened the door to the stadium shows that took over in the years that followed."Peace and love started to come in. That's what sunk it eventually. Nobody wanted to go to clubs anymore. They wanted to stay outside and smoke weed."

tweet this

In fact, Led Zeppelin would be one of Showco's first clients, hiring them to exclusively produce the band's concerts starting in the early '70s. "I can remember when Led Zeppelin came [to Dallas] in 1977, it was a huge deal that they had lasers," says Jeff Liles, the current artistic director for the Kessler Theater, who attended that year's Memorial Auditorium show as a high school student. "Showco had a huge influence. ... They took bands' touring shows to a totally different level."

There's little evidence today to suggest that Soul City ever existed. Its former address, 4174 Greenville Ave., is now a Vespa dealership. The entryway where Harmon's desk once greeted fans is now part of the showroom, while the corner where the stage once stood has been converted into offices. The only semblance of the old layout is in the back of the building, where the dressing rooms were once situated.

"You'd be surprised how many people come in here saying, 'I remember when this place used to be Bowley and Wilson,'" the store's current owner, Randy Campbell, says, referring to the comedy club that took over after Soul City closed. "But there are others who say, 'No, I remember when it used to be something else,'" adds Campbell.

"You'd occasionally hear Showco people talk about it," Liles says, who went on to work at Deep Ellum's first club in the 1980s, Theater Gallery, and the first incarnations of Club Dada and Trees. Today, the Kessler, itself a small-capacity "listening room," is something of a spiritual descendant of Soul City. "But they were talking about it twice removed. It's not like they actually went there."

Even those who were there have scarcely anything in the way of keepsakes, be they photos or memorabilia, much less recordings of the shows. "It was all moving so fast and we had so much to do," laments Wynne, who only has some fliers and old newspaper clippings to show for Soul City's nearly two-year run. "I can't imagine why we didn't have a record of all that stuff. At the time, it just seems like it will go on forever."

"I meet so many people now who tell me they snuck in there or they went there," Wynne says.

"Some got engaged there. Some met their sweethearts there," Levenson points out.

Wynne gets excited as a thought occurs to him: "I'd love to clean [the store] out some night and do something like that in there. Now that would bring out some people," he says. Then he pauses. "A lot of the people who went there now are dead."

Morton spent 10 years in Dallas before he was traded to the New York Giants, and eventually finished his career with the Denver Broncos, whom he led to another Super Bowl. He lives in California now but says his favorite memories of Dallas are from Soul City. "That was the standout," he says. "[They] really kind of saw into the future. I think a lot of people looked at that and said, 'Hey, we could do that,' and it sort of really took off."

"It was ahead of its time. You don't see too many people to this day who do what they were doing there," Patterson, who still fronts his Mustangs, says of Soul City. "You could dress up and see nationally, internationally known artists for that kind of money? You don't see much of that happening around here today."