John Anderson

Audio By Carbonatix

Theresa “T” Barksdale considers herself a diehard Stevie Ray Vaughan fan. Her back is decorated with a mural to the late Texas guitarist. The ink has personal significance: She and her older brother, who died last year, designed it. She still remembers him sharing the recordings of Vaughan igniting his Stratocaster “Number 1” onstage at various clubs along Sixth Street in Austin.

With Vaughan’s death in 1990, the master 35-year-old Texas blues guitarist became a legend.

“The music just spoke to me, man,” Vaughan once said. “I loved the feeling you could get from playing and the feeling other people could get when you played for them.”

The spirit of giving that Vaughan embodied inspired a pair of Dallas bikers to found the SRV Remembrance Ride and Concert 23 years ago. The event raised money for the Stevie Ray Vaughan Memorial Scholarship Fund for musically gifted children.

Barksdale, who owns T’s Blues & Tattoos in Austin, later took the reins of the SRV Remembrance Ride and Concert. Running the charity event proved difficult; she found herself trying to get the books in order and repair its reputation.

“There was several times I was told bridges were burned with the event,” she says. “I think things were done that people were not happy about.”

These headwinds never stopped Barksdale. But in June, as Barksdale was in the midst of planning the 23rd annual event, this time in Austin, a letter arrived that put it into a tailspin. It was a cease-and-desist letter from an attorney for Jimmie Vaughan, Stevie’s brother.

“Please take note that Jimmie Vaughan has asked that I notify you that he has not consented to your use of the name or likeness of his brother or the initials ‘SRV,'” Ronald Habitzreiter wrote. “Further, you may not commercially exploit or use in any manner the likeness or name of Stevie Ray Vaughan or the secondary meaning of SRV, whether or not the same is cloaked in a charitable or non-profit related event.”

The letter said that while the family gave consent in 1995 for a single event, Vaughan wanted to re-approve the event every year. “No person has the right to the continued use of the name SRV Remembrance Ride,” the letter concluded.

Barksdale was stunned. She’d already secured $15,000 in sponsorships, something her predecessors hadn’t been able to do since 2010. She also lined up some bands and found two Austin venues, Hardtails Bar and Grill and Ernie’s On The Lake, to donate their space, something she says she couldn’t find in Dallas.

It’s become more difficult for Barksdale since the cease-and-desist letter arrived. Bands have dropped out, and the former vice president, Shon Beall, contacted sponsors and told them the ride was over, prompting Barksdale to send a cease-and-desist letter to get him to stop.

Beall also told Vaughan’s attorney the event was over and that he can’t understand why Barksdale is determined to host the ride.

“Of course, I’m trying to cover my ass,” he says. “I can’t afford to get tied up in a lawsuit.”

Barksdale isn’t quitting. She says that despite the letter, she’s trying to keep the ride alive because she believes in its cause. She says the event can be saved from its past.

“I’m not sure why Jimmie’s attorney sent the letter,” Barksdale says. “I’m the one who is trying to repair it.”

A Stevie Ray Vaughan mural adorns the wall above the entrance to the performance hall at Greiner Exploratory Arts Academy in Oak Cliff.

Brian Maschino

Jeff Castro wanted to do something to memorialize Stevie Ray Vaughan after the guitarist’s helicopter crashed in August 1990 outside of East Troy, Wisconsin. Castro’s older brother first took him to hear Vaughan ignite his guitar onstage at the Bluebird Blues Club in Fort Worth about the same time he introduced Castro to motorcycles. It’s a love affair that later led him to a leadership position in the Texas Motorcycle Rights Association.

“I started at a young age in motorcycles and blues,” he says.

A couple of years later, Castro made some calls to find out what it would take to put up a statue of Vaughan in Oak Cliff and approached his councilman about renaming Hampton Road to Stevie Ray Vaughan Boulevard. He was put off by the red tape.

“It was like having Elvis but nothing in their town to honor him,” he says. (It took Dallas city leaders nearly 30 years to honor the Vaughans; a statue of both brothers is set to be unveiled in Kiest Park next month.)

Castro met Jim Haynes at a motorcycle rally Castro hosted to raise money for the Texas Motorcycle Rights Association’s fight to repeal the helmet law in the ’90s. Haynes, who rode with the Boozefighters club, was also an avid Vaughan fan. He’d custom-painted Vaughan in his signature black gambler hat on the rear fender of his motorcycle. Like Castro, Haynes planned to memorialize Vaughan, but he wasn’t thinking about building a statue or renaming a road.

Instead, he wanted to host a remembrance motorcycle ride that would thunder through Oak Cliff, and he asked Castro to help.

Castro had pulled off a few successful biker rallies in the early ’90s to raise money for the fight to repeal the helmet law. He says Haynes’ plan was a “badass idea,” and he figured he could pull it off because, as a business owner and blues fan, he knew quite a few people in Oak Cliff and the Dallas blues scene.

They planned to kick off the bike parade at Kiest Park, which had been the site of a candlelight vigil for Vaughan, and end it at the Veterans of Foreign Wars Post 4477 in Oak Cliff. A concert by various blues artists and friends of Vaughan would take place on a flatbed trailer in the VFW post’s parking lot. They planned to donate the money raised to the scholarship fund established three years after Vaughan’s death.

Haynes told Kim Young, the scholarship’s founder and executive adviser, about the pair’s plans to host a remembrance ride. Castro and Haynes wanted permission from Vaughan’s mother, Martha, before they started advertising the event.

“He very much wanted to follow her wishes,” Young recalls. “The dream of the scholarship fund has always been to raise money and give more scholarships. It was very obvious that they cared about Stevie as much as I did and they wanted to do something positive. It was just another way to honor him.”

Young asked Martha Vaughan if she’d be willing to send a letter giving her blessing, and she granted them permission to use her son’s “hat and guitar image.”

“Once again I wish to thank you on behalf of the Vaughan family for your efforts and work to honor Stevie Ray and to do all of this in remembrance of him to help give our children a future,” she wrote in a letter dated Aug. 30, 1995. “Our kids ARE our future and we must help them get a good education if they are to become productive citizens.”

Maria Guadalupe Vargas received the Stevie Ray Vaughan scholarship in 1995. Now she teaches orchestra at Greiner Exploratory Arts Academy.

Brian Maschino

Maria Guadalupe Vargas was one of those kids. She didn’t know much about Stevie Ray Vaughan in 1995, when her orchestra teacher at W.E. Greiner Exploratory Arts Academy told her about the college scholarship in his name. She was in eighth grade, a talented 14-year-old violinist whose family lived paycheck to paycheck in Vaughan’s neighborhood of Oak Cliff.

Qualifying for the scholarship was fairly simple; she had better than the required “C” average and planned to study music in college. All that stood in the way was an audition in front of a panel of music industry judges.

Vargas was nervous, but it didn’t deter her. She was awarded the Vaughan scholarship for $1,000.

Vargas now instructs music students at Greiner. For nearly a decade, she has helped to shape seventh- and eighth-graders who continually win awards and garner recognition. She teaches orchestra and started a mariachi program. She also plays in a mariachi band on the weekends.

“My parents were extremely proud when I won the award,” Vargas says. “I was speechless.”

The motorcycle parade traces through Oak Cliff in 2007.

Michael Clay Smith

An army of bikers roared out of Dallas’ West End as part of the 14th annual SRV Remembrance Ride in October 2008. About 1,500 of them planned to descend on Cowboys Concert Hall in Arlington for a night of blues from Lance Lopez, 9-year-old Tallan “T-Man” Latz and Bugs Henderson. They came together to raise money for the SRV Memorial Scholarship Fund.

Ride volunteers told The Dallas Morning News that they expected to raise at least $40,000 through ride fees, concert tickets and merchandise sales. No one could blame them for being optimistic. The public support section of the group’s 2009 tax form shows that the 2007 ride, which Johnny Winter headlined, made $75,000. But according to the Communities Foundation of Texas, a nonprofit that manages the Vaughan scholarship fund, none of that money was donated.

Castro quit hosting the ride in the early 2000s. At that time, the event had grown out of the VFW and into the Bronco Bowl. The organization had become a nonprofit, and he says hosting the ride took a lot of work, especially after he got busy with his father’s tree business.

But volunteers say Castro’s resignation had more to do with the Scorpions outlaw motorcycle club. Ric Choate, who oversaw event production at the time, says the Scorpions began claiming the ride as theirs and putting their bikers at the front of the parade. Then an altercation broke out at the Bronco Bowl, he says, and they tried to “strong-arm” Castro.

“He didn’t stand his ground,” Choate says. “He told me he didn’t feel safe.”

Castro handed the event over to Choate, who says he called the president of the Scorpions, whom he knew, to clear things up. The Scorpions, he says, were upset about other bikers wearing Oak Cliff patches on the backs of their cuts.

“He said the city was their territory,” Choate says. “I had to explain it wasn’t like that.”

But Castro says Choate just wasn’t on his bike as often as he was.

“I was heavily involved with bike clubs, and he wasn’t on his motorcycle, running into them after the ride, so he wasn’t seeing them, wasn’t having to deal with them,” Castro says. “You try to get something good going, and something always happens.”

Randy James and Shon Beall present onstage at the 2016 SRV concert.

Michael Clay Smith

After taking over the ride in 2004, Choate sought the help of Shon Beall, and they served as president and vice president for more than a decade. The duo landed some notable blues legends to headline the benefit show. Louisiana guitarist Kenny Wayne Shepherd headlined in 2005 with Vaughan’s old band Double Trouble, followed by blind bluesman Jeff Healey in 2006.

Until recently, advertisements on the group’s website claimed that 100 percent of proceeds from the ride and concert benefited the SRV Memorial Scholarship Fund. Tax forms show otherwise.

In 2005, for example, the ride reported earnings of more than $60,000, of which $10,000 was donated. In 2006, it raised about $30,000 and donated $3,000. The 2008 ride raised more than $53,000, but only $10,000 went to the scholarship fund.

The ride made no donations in 2007, 2009, 2012, 2015 or 2016.

“What Theresa [Barksdale] should have done is when we told her we were closing the company, she should not have closed the bank account and kept the money to produce her own event,” Beall wrote in an email to the Dallas Observer. “We should have been able to give the last of the money in the account to the charity. She had no right to keep that money, and we’ve yet to see any receipts for any of her spending under our company, much less any of these cash withdrawals.”

Barksdale says she was left with only $5,000 last year after Choate took out the money he said the organization owed him – $9,225, according to financial records – for paying out of pocket for the headliner.

Former ride treasurer Jeff Horton, an accountant, says he had no control over what was donated. He simply collected receipts and managed the books, he says, blaming H&R Block for any discrepancies in the tax forms. Horton suggested contacting Beall, who in turn said he gave Horton all the receipts and that the former treasurer would be the best person to comment.

Choate says he never looked at the bank account. He says he asked about the books but was always told that everything balanced out.

Shon Beall, Ric Choate and members of the Vaughan family present onstage at the 2015 event.

Michael Clay Smith

“With a grassroots operation, it’s difficult to keep up,” he says.

Choate says the event had been rained out a couple of years. But the group donated $5,000 in 2010, when it showed a loss because of rain, and claimed $8,557 was left over at the end of the year.

Looking at the ride’s tax records is like gazing into a fun-house mirror. In 2013, it began the year with $12,945, donated $6,000 and ended with $11,104. It donated $5,000 in 2014 and ended the year with $20,715 in the bank. It made no donation in 2015 but showed it had $23,603 in the bank at year’s end, and it ended 2016 without a donation but with $15,384 left in the bank.

“Just like any other event that is produced, there are good years and bad years financially,” Beall wrote in another email to the Observer. “Sometimes we had big numbers with ticket sales and merchandise sales, and some years the turnouts were low.”

Financial records and copies of checks obtained by the Dallas Observer show that Beall and Choate had been writing themselves checks from the ride as reimbursement for a number of expenses, sometimes noted on the bottom of a check. Choate wrote a $6,000 check Oct. 7, 2006, to pay Beall for an unspecified expense. Beall wrote himself a $2,527 check Oct. 24, 2007, for “cash and insurance loans,” then followed with a $9,850 check in late October 2008 for “2007-2008 shirt reimburse.” He wrote a $2,213 check Dec. 23, 2009 for a “shirt loan.”

“A lot of those years, I had to pay up front [for merchandise],” Beall says. “All staff and board of directors worked on a volunteers basis; we never reimbursed ourselves for any personal expenses.”

Choate also wrote himself a $6,500 check Oct. 16, 2007, for a reimbursement he failed to mention.

“There is no way Ric [Choate] and Shon [Beall] were having to front that much money,” Castro says. “When I gave them the ride, we had sponsors and money left over.”

The checks and lack of donations some years weren’t the only things raising red flags for Barksdale. Choate and Beall had auctioned a custom-built, $30,000 motorcycle in a $20 raffle in 2006, yet somehow it still remained in Choate’s possession.

Choate claims they paid for some of the expense out of their own pockets. They also paid $1,700 in hotel expenses for the Cartel Customs staff to bring the chopper to the annual Republic of Texas motorcycle rally in Austin.

“Orange County Choppers was popular at the time,” Choate says of spending money that could have benefited at least 30 eighth-grade music students. “We thought it would bring in more people.”

An Australian man won the motorcycle, but he didn’t want to pay the expenses to ship the chopper home, Choate says, so he gave it back to the ride a month after he won it. It was never auctioned off again.

“It was very uncomfortable,” Beall recalls. “It was not like his [Choate’s] personal toy, and he only used it to ride in the parade.”

Suspected mismanagement of the ride led Young, the scholarship founder, to ask Communities Foundation of Texas to check into the donations. Barksdale says she spoke with the foundation and was told that if the SRV Remembrance Ride wasn’t able to make donations, it would need to remove the foundation’s logo from its website.

Castro claimed never to have a problem raising money to donate. “They should have never taken it out of Oak Cliff,” he says.

Theresa Barksdale took over the charity shortly after the 2016 Ride.

John Anderson

Barksdale started attending the ride when she heard about it in an online chat group for Vaughan fans. Through the ride, she got to know many in Vaughan’s extended family and his mother. Sometimes she’d attend the event and match the ride’s donation.

Barksdale says before she took over the event, she witnessed signs of mismanagement and heard rumors of theft, but she thought she could help turn the ride around.

She first took on booking bands for the 2016 event. She tackled her new task as if she were tattooing a new art piece: with passion and persistence. She scored big when she landed the “Texican” rock band Los Lonely Boys as the headliner. She also came up with a new way to keep track of ticket and merchandise sales.

“I’m friends with the volunteers, and a lot of them complained that there wasn’t any transparency,” she says. “Then they [Beall and Choate] threw a wrench in it and went back to the old way of doing things.”

The handbook also mentioned the need for sponsors. “Event needs paying sponsors,” Beall wrote. “Right now the event has none.” Beall and Choate’s last sponsor was Hooters in Dallas. Its parent company, Texas Wings, quit sponsoring the ride three years ago, according to the handbook, but tax forms show Texas Wings last donated in 2012.

It didn’t take Barksdale long to figure out how costly it would be to host a large ride and concert, even with donated venues. She projects the 23rd annual ride will cost about $30,000. Beall and Choate said they spent nearly $33,000 on the 2013 event; about $15,000 in 2014; more than $22,000 in 2015; and $50,000 in 2016.

When she took over the event, Barksdale decided to focus more on the kids who benefited from the scholarship. She added a “click here to donate” link to the foundation’s website and embedded a short documentary about the scholarship and its recipients.

“It’s because her heart is in the right place,” Young says.

Last year, 20 students qualified for the $4,000 Vaughan scholarship, but only 10 received it. It was five more than usual, Young says. She also notes that the ride isn’t the only source of income for the scholarship. Martha Vaughan and her son Jimmie donated for years. The scholarship has raised more than $800,000 since its founding in 1993.

Thomas Kreason, who runs the Texas Musicians Museum in Irving, also plans to host a concert this month to raise money for the scholarship fund. It’s the second year he’s hosting an event. But instead of a biker parade, he’s planning a car show. He’s calling it the SRV Scholarship Fund Kick Off Party. Jimmy Wallace and the Stratoblasters are headlining the event.

“We’re being very careful how we use ‘SRV’ because they got the cease-and-desist letter,” Kreason says.

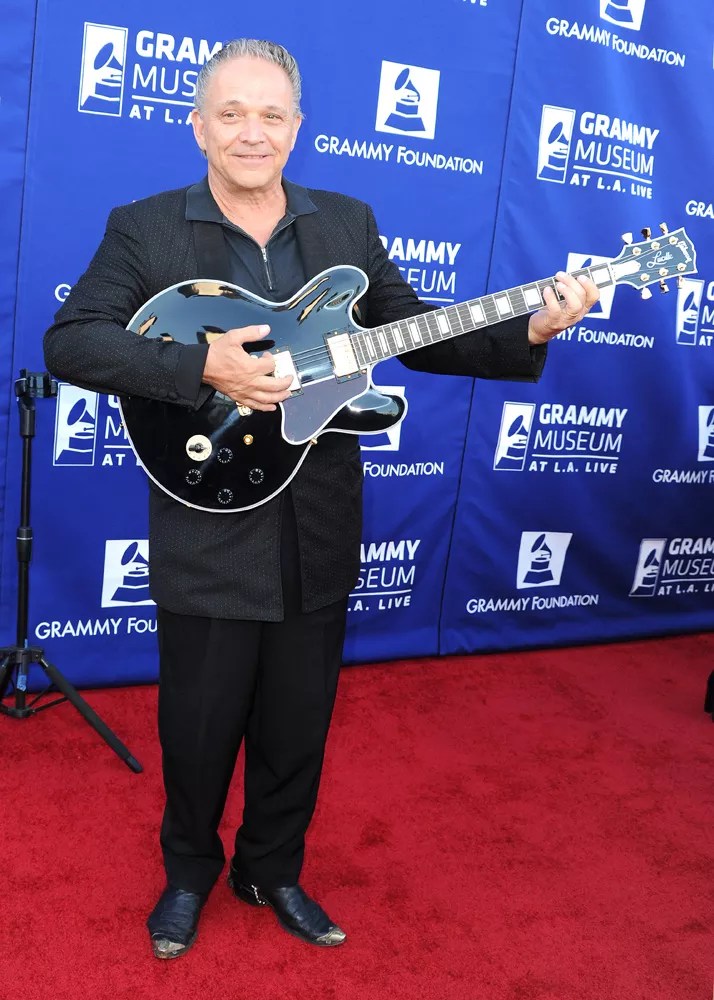

Jimmie Vaughan doesn’t want any events to commercially exploit his brother’s name.

PG / Splash News/Newscom

Ronald Habitzreiter, Jimmie Vaughan’s attorney, says this isn’t the first time he’s tried to shut down the SRV Remembrance Ride. He sent a cease-and-desist letter May 23, 2001, claiming that the event required his client’s consent, which he hadn’t given. Habitzreiter also said it couldn’t “commercially exploit or use in any manner the likeness or name of Stevie Ray Vaughan or the secondary meaning of SRV.”

An email Castro received from Vaughan’s mother shortly before Habitzreiter’s letter arrived claimed otherwise.

“Jeff Castro asked me approximately seven years ago for permission to put on a SRV Remembrance Ride,” Martha Vaughan emailed May 17, 2001. “I gave my permission. He has since continued to put on the event each successive year and has maintained communication with me regarding any changes that he wished to make. [He] has my approval to continue with the annual event.”

She died in 2009, and the charity event lost the only Vaughan family member who defended it.

Habitzreiter claims the SRV Remembrance Ride is violating copyright by selling merchandise. In 2016, according to the tax form, it sold $20,000 in merchandise such as an SRV mousepad, SRV posters and SRV bandannas.

“They sell sponsorship, T-shirts [and other merchandise] and use it for their own personal benefit,” Habitzreiter says. “It makes my stomach turn.”

Barksdale says she’s doing her best to abide by the most recent cease-and-desist letter. She dropped SRV from the event’s name and purchased a new domain at remembrancerideandconcert.org. She’s also careful not to mention Stevie Ray Vaughan’s name as she advertises the event in Austin. She even replaced his image on the shirt with the 2017 ride’s headliner, Rick Derringer, a blues guitarist and Grammy Award-winning producer.

The ride wraps up as the crowd collects for the concert at the 2015 event.

Michael Clay Smith

She wanted to start a nonprofit under the same name, but her would-be board of directors is reluctant to make it official because of Habitzreiter’s letter. Barksdale says she doesn’t want to upset Jimmie Vaughan but feels that she can’t let potential scholarship recipients down, especially after she received Young’s approval to advertise that her event would benefit the Vaughan scholarship.

“The Ride, operating smoothly on all cylinders, has the potential to encourage even more children to finish high school and to help them go on to college,” Young wrote in an email.

Even with the scholarship’s backing, Barksdale is concerned. She doesn’t have the money to fight a legal battle with Jimmie Vaughan and the New York attorneys.

“I would love to keep this going,” she says. “But I’m scared that this [is] going to get shut down and the scholarship is going to suffer.”