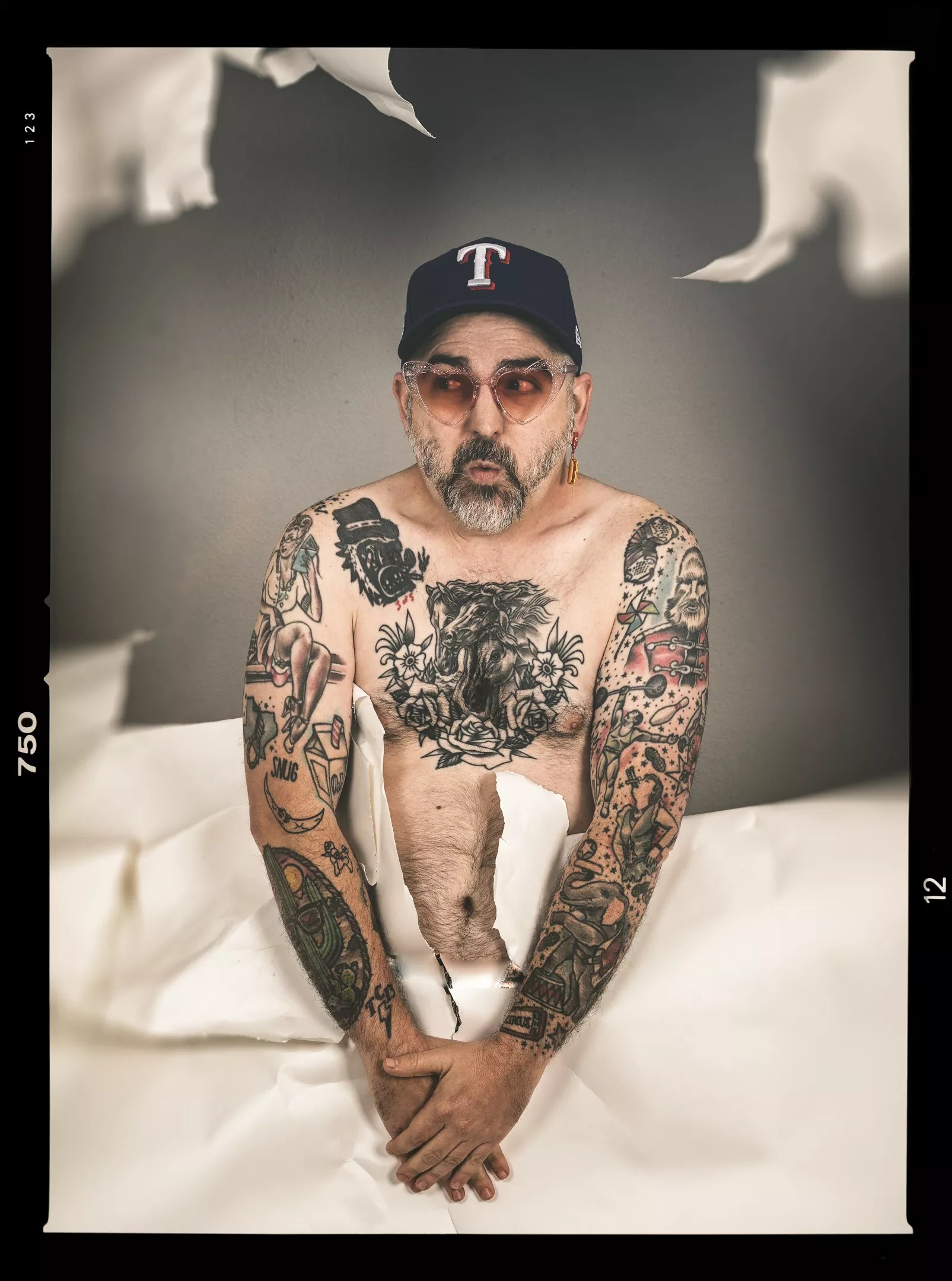

Mike Brooks

Audio By Carbonatix

It’s the night before Thanksgiving, and Vandoliers, Joshua Ray Walker and Jaret Ray Reddick are playing a show at Dallas’ Longhorn Ballroom. The dynamite country bill was advertised as a Friendsgiving celebration, and that distinction is right on the money.

Building community is a core tenet of the Vandoliers’ values. A country band formed by Josh Fleming, the former frontman of punk band The Phuss, the group has always been about bringing people together and finding common ground. At this show, there is obvious love and admiration between the artists. It’s the kind of event where you bump into at least three people you know. The sense of community is palpable.

Josh Fleming of the Vandoliers says the band has always been about bringing people together to find common ground.

Mike Brooks

“It started as having my punk friends and my country friends come together at the same show,” Fleming says. “Now it’s so much more than that.”

The newly reopened Longhorn, a historic venue that’s welcomed both punk and country fans in its day, is the perfect setting for a show that has everything people want out of a country concert. It’s fun and raucous and a bit rowdy. The Vandoliers bring a little Wild West energy to every live performance.

There are also intentional moments of tenderness and inclusivity throughout. The guys are affectionate with each other onstage. On more than one occasion, Fleming moseys on over to bandmate and multi-instrumentalist Cory Graves to plant a kiss on his cheek. With effortless finesse, they strike the delicate balance of being rock ‘n’ roll cowboys without riding the horse of toxic masculinity.

In the latter half of their set, Fleming gives an extended shoutout to mental health nonprofit Foundation 45, which had a booth set up in the back of the room where attendees could pick up a pamphlet or a button with slogans such as, “Live Fast, Die Old.” The Dallas-based organization assists those struggling with mental health and addiction and has special support groups for LGBTQ+ individuals and women of color.

“The central mission of this band is to be a positive force for good,” Fleming says. “And even by doing that and by being there for everyone with that mindset, sometimes it does ruffle feathers.”

The band is aware that country is still associated with a more conservative and regressive base, so they want to make one thing clear.

“Vandoliers is for everybody,” Fleming says. “Except for dicks.”

Guys and Dolly

Country music is experiencing a spike in mainstream popularity, and the data speaks for itself. Four country songs reached No. 1 on the Billboard Hot 100 in 2023, the most in one year since 1975. For comparison, hip-hop also had four songs hit No. 1 last year. Going off charts alone, the two genres appear to have equal cultural relevance. This would’ve been inconceivable to pop radio listeners just a few years ago.

Of the four No. 1 hits, two became lightning rods for controversy. Jason Aldean’s “Try That in a Small Town” faced backlash for glorifying vigilante gun violence (the music video was even widely criticized for intercutting news footage of a Black Lives Matters protest with clips of Aldean singing in front of Maury County Courthouse in Tennessee, the site of a 1927 lynching).

“Rich Men North of Richmond,” the uber-populist breakout single from Virginia-based singer Oliver Anthony, debuted at No. 1 in August. Its lyrics, which rail against everyone from elites who want to control what you think to people who use welfare checks to buy Fudge Rounds, purported to speak to concerns of the working class and received praise from conservative heavy hitters ranging from Rep. Marjorie Taylor Greene to blogger and self-described “theocratic fascist” Matt Walsh.

Beyond the Billboard Top 100, country music as a whole has captivated a different audience than that of Aldean and Anthony: Generation Z, people born between 1997 and 2010.

Country music’s influence on Gen Z culture is far-reaching, a recent and unexpected example being the new Hunger Games movie, The Ballad of Songbirds and Snakes. It has a soundtrack of original songs inspired by Appalachian country that are a hit with young fans of the franchise. Even genres adjacent to country, such as folk-rock, have produced artists such as Noah Kahan and Phoebe Bridgers, whose candor on subjects such as mental health has made them rock stars among Gen Z.

A study from Relative Insight suggests that Gen Z might be drawn to country music because they’re more open-minded and less likely to judge a song or artist based solely on preconceived notions of their genre. In other words, you’re less likely to hear a zoomer say that they listen to “everything but country” than you would Millennials or Gen X.

Open-mindedness is also reflected in Gen Z’s politics. According to a report from Pew Research, they are more likely to have progressive views on LGBTQ+ and race issues. A recent Gallup poll shows that one in five Gen Z adults identifies as LGBTQ+.

People gravitate toward music they feel represents them and their values. For Gen Z, who value relatability and authenticity, country music, a genre that traditionally venerates lived experience through storytelling and gives the establishment castaways a bully pulpit, does just that.

Bryson Coffey is a 19-year-old college student living in North Texas. He identifies as gay and is also a lifelong country fan.

“I like to listen to country music that embraces my personal values, like being authentic and loving people for who they are,” Coffey says. “And, of course, crying my eyes out to ‘Teardrops on My Guitar’ by Taylor Swift.”

His relationship with the genre echoes that of many who grew up in the South. He grew up on country and was raised on classic artists such as Dolly Parton. For a time, modern country, which he perceived as promoting misogyny and alcoholism, left him feeling jaded about the genre, but he eventually discovered artists who reflected and affirmed his values and reignited his love for country. His favorites include Kacey Musgraves, Orville Peck and, as always, Dolly Parton.

“With the rise of many upcoming queer and POC artists breaking into the scene, they are really challenging the precedent,” Coffey says. “It is no longer just for straight white people. There are now country artists I can listen to and relate to as a queer person, and I didn’t have that as a kid.”

Last year’s inflammatory hits notwithstanding, countless country artists have risen to this moment, many of them from North Texas. Dallas native Joshua Ray Walker made a statement on gender stereotypes last year with the release of What Is It Even?, a collection of covers of songs by female pop artists. The album and its cover art, which depicts Walker in a pink, furry shawl, take an artistic stand against detractors who have mocked him for appearing too feminine. The name of the album is even a defiant direct quote from a hateful comment he received.

Maren Morris has been vocal about her progressive beliefs.

Mike Brooks

Arlington native Maren Morris has been vocal about her progressive beliefs. She is an advocate for more diversity in country music and a staunch ally of the LGBTQ+ community, stances that have made her a polarizing figure among country fans. After being called a “lunatic” by former Fox News host Tucker Carlson, Morris raised $100,000 for transgender charities by selling shirts that read “Maren Morris, Lunatic Country Music Person.”

Another Arlington native, Mickey Guyton, made history by becoming the first Black woman to be nominated for Best Country Solo Performance at the 63rd Grammy Awards for “Black Like Me.” The song details her experience as a Black woman in country music, containing lyrics such as, “If you think we live in the land of the free / You should try being Black like me,” and was released in the wake of the 2020 Black Lives Matter protests.

Dallas trio The Chicks (formerly The Dixie Chicks) will forever be known for their comments about the Iraq War in 2003 (and their subsequent cancellation by conservative country fans), but that was far from their last political statement. Their recent concert tours have included bold feminist and anti-racist messages, including projecting the names of victims of police brutality onto an LED screen while performing their protest anthem, “March March.”

Artists who openly love and advocate for their fans in marginalized communities give listeners like Coffey hope, despite the reactionary fans and musicians who are still prominent in the scene.

“I really do hope that in the future, this type of country music will not be seen as groundbreaking, but just the norm,” he says. “We will all just love each other a little more and listen to the music we love.”

Y’allternative

In the spirit of their punk roots, the Vandoliers have never shied away from making a statement. These days, however, they’ve been feeling the weight of their platform a little more.

“Lately, I’ve had this realization that when we do these things, most of the time we just assume no one’s going to pay attention. You know?” Fleming says with a laugh. “We don’t really understand that people like … like our band.”

In March of last year, the Vandoliers played what would’ve otherwise been a benign show to about 80 people at The Shed Smokehouse & Juke Joint in Maryville, Tennessee. The show made national headlines thanks to a certain last-minute costuming choice: The all-male band performed that night’s set in dresses.

This was done in response to the anti-drag legislation that had passed in Tennessee that day. House Bill 9, which was drafted by Tennessee state Sen. Jack Johnson and signed by Gov. Bill Mee, restricts “adult cabaret performances” (including “male or female impersonators”) in public or in the presence of children. Critics of the law, such as the ACLU of Tennessee, claim that it will not only be used to target drag performers but Tennesseans in general whose gender expression might be illegal according to the bill’s vague wording.

But when the Vandoliers donned their frilliest dresses and walked out that night to Shania Twain’s “Man, I Feel Like a Woman,” it did not feel like a political stunt to them. It just felt like the right thing to do.

“We just thought it was kind of horseshit,” says Graves of the legislation.

“Within our platform, we’ve been a part of the trans community and queer community,” Fleming says. “We have friends in this community. It was just kind of our way of showing our platform where we stood on it. And that’s where we wanted to be. And obviously, it took off.”

With country music being a battleground for the omnipresent culture war in recent years, the band finds it more important than ever to let their audience know where they stand.

“There are people out there thinking these aren’t safe spaces,” Graves says of the culture at country shows. “And I guess some of them aren’t. We want to be the antithesis to that. If we’ve got to kiss each other onstage, or whatever we do that makes the assholes uncomfortable and stay home so that everyone else can feel safe, we’ll do it. I just want our shows to be a safe space and for everyone to feel welcome.”

While the band has always been willing to stand up for what they believe in, they’re hesitant to call statements like the one they made in Tennessee “political.”

Cory Graves of the Vandoliers thinks the anti-drag legislation in Tennessee is “horseshit.”

Mike Brooks

“We really don’t get political,” Graves says. “Like, almost ever.”

“If anybody is ever like, ‘Oh my God, the Vandoliers are liberal,’ they haven’t been paying attention,” Fleming adds. “But, at the same time, it’s not an overt act ever and this wasn’t one of those either. We thought it was important to us. We wanted to show our support.”

The band’s insistence that they’re not political might raise some eyebrows, seeing how the performance in dresses was a direct response to a political event, and they performed at a rally for Sen. Bernie Sanders during his 2020 presidential campaign. The perceived contradiction is not lost on them.

“You say we’re not political, Cory, but we talk about body positivity, you guys take off your shirt,” Fleming says to Graves. “We’ve talked about mental health onstage for the last five years, we’ve played political parties, we’ve done the dress thing … “

“I just don’t consider any of that politics,” Graves replies. “That’s just, like, human issues.”

The dresses made headlines, but they’re far from the first statement the band has made onstage. The guys are well acquainted with using fashion to send a message.

“‘Protect Trans Kids’ is a shirt that I wear anytime we have a big show. I wore it in Anaheim for the Flogging Molly show,” Fleming says. “Cory has one that’s like, ‘If you don’t like abortion, chop your dick off.’ That’s my favorite.”

Taking a firm stance on these issues has become more crucial than ever to Fleming since the birth of his daughter.

“My kid has softened me up so much,” Fleming says. The softness can be heard in his voice. “My job right now is to tend to her garden and protect it and put in seeds of hope and joy and patience. And if I can do all of that while setting an example of, you know, we’ve gotta love people. That’s the bit.”

Fleming hopes that the band’s message of love doesn’t just create a safe space for fans at their shows, but an accepting environment for whoever his daughter grows up to be.

“Her gender is not my responsibility,” he says. “I want her to feel like her dad will accept her for whoever she wants to be, whenever she’s ready to do that.”

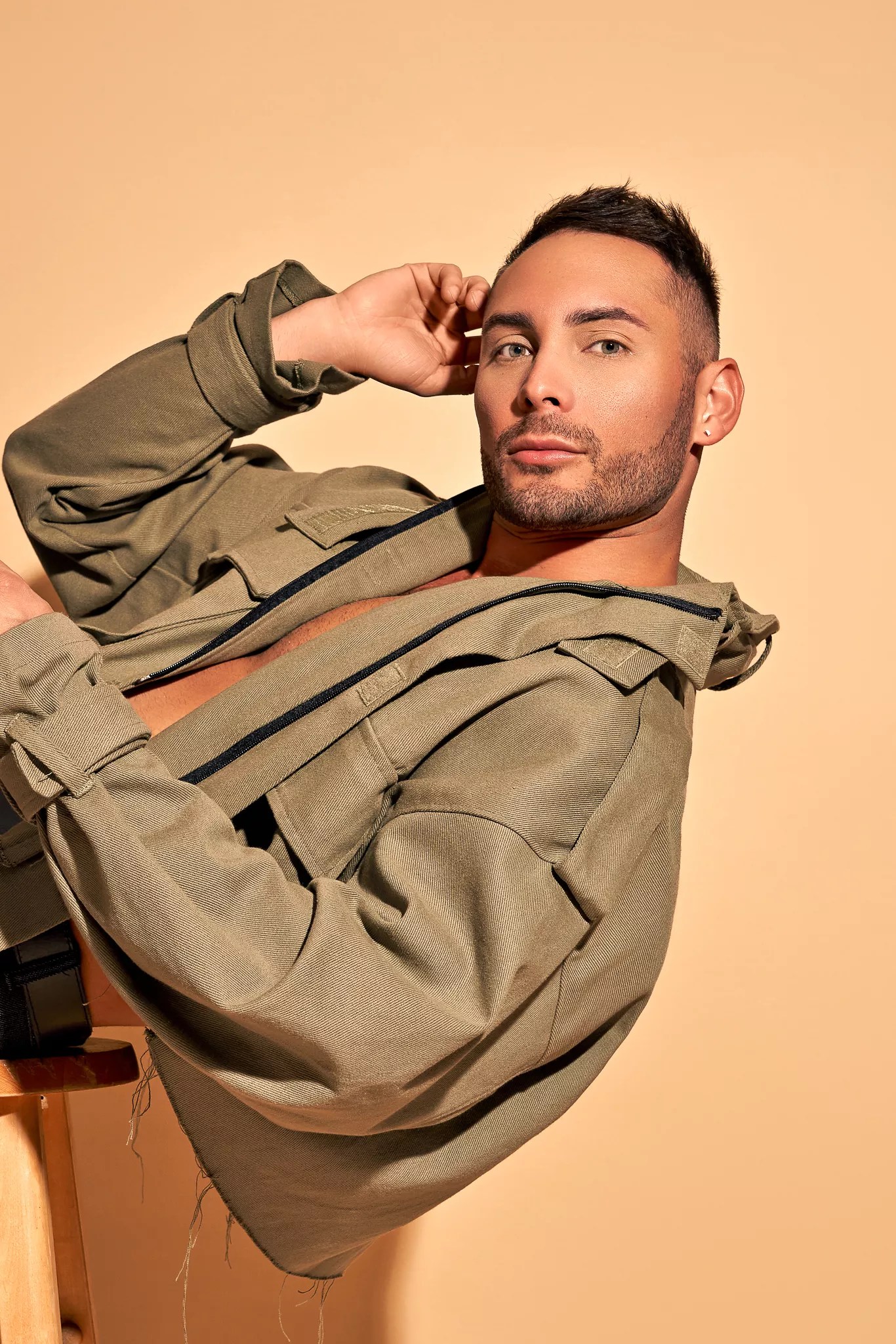

Kameron Ross is a gay country artist based in Dallas.

Marcos Covos

Born This Sway

The story of the music video for “Sway,” a song Dallas-based country artist Kameron Ross released last year, takes place at the Round-Up Saloon in Dallas. As Ross, who is gay, prepares to perform for a crowd of rugged, red-blooded country music fans, he confides in drag queen Alyssa Edwards, a former RuPaul’s Drag Race contestant and native of Mesquite.

“I just can’t do it,” Ross says to Edwards. “I can’t go out there and perform for these people. They’re just … they’re not going to like it.”

“So what?” Edwards replies. “You mean to tell me every gig that you book, you’re going to put on a mask because you’re afraid of offending someone for being you? Baby, please.”

With Edwards’ encouragement, Ross takes the stage in a sequined jacket and the show begins. The crowd is skeptical at first, and as the song builds up to the chorus, Edwards calls in some backup: a shimmering squad of local drag queens ready to hype up both Ross and the crowd.

By the end of the video, Ross’ performance is such a success the cowboys and drag queens are square dancing, throwing darts and playing poker together like old friends. Against all odds, once again, community and the pursuit of common ground have prevailed.

The narrative of the “Sway” video parallels Ross’ own life and career: pursuing a career in country music as a gay man, fearing backlash from intolerant fans and coming out on top with support from the LGBTQ+ community.

“Although we see a lot of headlines about some of the progressiveness in country music, […] what a lot of people don’t see is the backlash that happens afterward,” Ross says. “Many fans start to say that they will boycott award shows or artists like that for becoming too ‘woke.’ And I laugh at that because they aren’t becoming ‘woke.’ They’re trying to become equal.”

Ross has a lifelong devotion to country music, going back to a Shania Twain concert he attended when he was 8 years old. He began pursuing his music career soon after and went on to release his debut album, I’m Done Lovin’ You, in 2006 at the age of 16.

When he came out as gay in his early 20s, however, he quickly realized the effect his identity could have on his career. He had seen it happen to other queer country artists.

“Ty Herndon, for example,” Ross says, referring to the first mainstream male country singer to come out as gay. “Ty’s a friend of mine. Once he came out, his career kind of completely shifted.”

After coming out, Ross felt the need to take a step back from music for a while.

“It was something I needed to figure out,” he says. “I wasn’t sure if, as a queer artist, I would be accepted in the same sense as someone who identifies as straight and how hard that would make things for me.”

Ross credits his found family in the LGBTQ+ community (including his fiancé, Dallas-based baker Lio Botello) with helping him find his voice and supporting the second, more authentic act of his music career. To Ross, the “Sway” music video does more than provide a fun and thought-provoking story to go with the song. It’s an homage to the people who got him where he is today.

“I do feel like we accomplished a really good message with it, you know?” Ross says. “We incorporate every bit of our community from the drag community, from our trans friends, every aspect of it, and we shot it at Round-Up. I think part of it was making it local and having that local representation. All the queens are local to Dallas.”

With anti-drag legislation dominating the news cycle, Ross felt it was essential to pay tribute to drag queens when creating the music video.

“It showcases the power that drag queens possess,” Ross says. “They have been champions in fighting for equality since before I was born. They do the most for our community and do it in heels. […] While they were targets of terrible bills around the country, I wanted to be sure to include them and make it clear that I support them just like they all support our community.”

The “Sway” video not only showcases Ross’ pride as a gay man, but contains a nod to his Latin roots as well, with Alyssa Edwards addressing him by his full name, Kameron Ross Martinez. Ross decided to drop his last name at the beginning of his career, but now feels it important to make his heritage known.

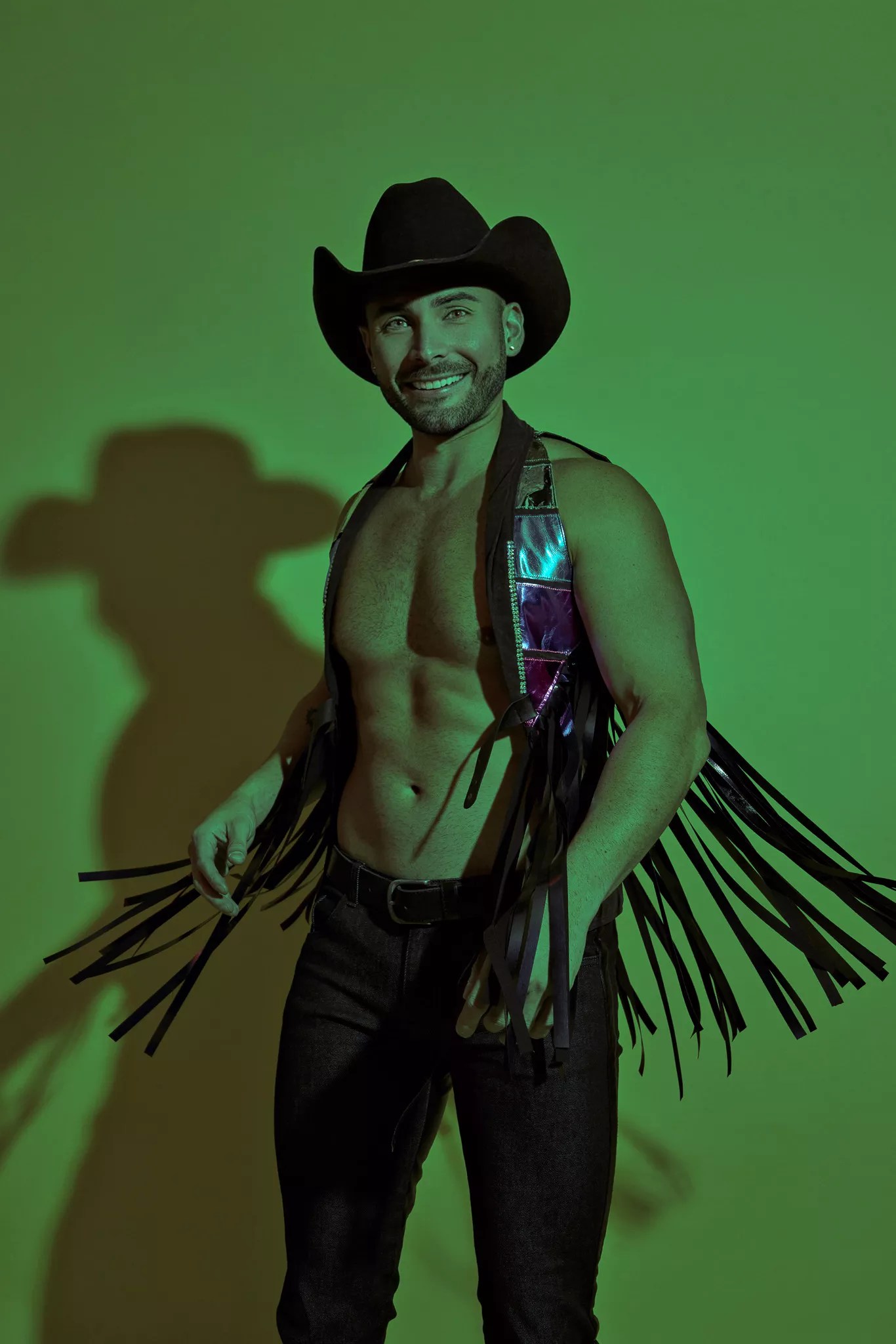

Ross was invited to perform at Capital Pride in D.C. last June.

Marcos Covos

“That is something that I’m slowly wanting to bring back into things,” he says. “It shouldn’t be me hiding the fact that I have a Latino last name.”

Last June, Ross was invited to perform at Capital Pride in Washington, D.C. It was a far cry from the setting depicted in the “Sway” video. The humble Texas saloon was traded for a large open-air stage, and instead of a small crowd of doubtful cowboys, he played to 475,000 queer people and allies who were ready and willing to accept him and enjoy his music. For Ross, the experience was exhilarating and overwhelming.

“I’m on stage, and I’m having a good time, but I didn’t know how many people were there,” he says. “You can only see so far. It just goes on for miles.”

Ross is optimistic about the future of country music and the role marginalized communities will continue to play in it, despite any backlash from conservatives.

“There is sort of a push and pull in country music,” he says. “But that’s why diversity in country music is that much more important right now. We are making a difference, so people of color and LGBTQ+ folks must keep fighting for country music because it’s our country too.”

While other progressive-leaning country artists have strayed from the scene in favor of more like-minded genres such as pop, Ross can’t picture himself making such a transition – partially because his singing voice is “very country,” but mostly because of his firm belief that he has as much right to be in that space as anyone.

“I love country music and no matter what, we’re staying and we’re going to fight this battle,” he says. “We’re here. We’re not going anywhere.”

The Outlaws

While country music has always had its conservative base, it also has a long history of controversial artists who pushed the boundaries of genre conventions.

Kitty Wells’ “It Wasn’t God Who Made Honky Tonk Angels” was banned from the Grand Ole Opry in 1952 for its daring message that women who get cheated on are perhaps justified in cheating right back. Loretta Lynn’s “The Pill,” an ode to the role of birth control in women’s liberation, was banned by several radio stations upon its release in 1975. Willie Nelson is a longtime activist and has advocated for environmentalism, marriage equality, drug reform and many other progressive causes. Johnny Cash testified in favor of prison reform in front of Congress in 1972 and his choice to perform in prisons is still considered radical today.

Nelson and Cash belonged to a movement known as outlaw country, a sub-genre that sprang up in the ’60s and ’70s in cities like Austin and Lubbock as a counterculture backlash to the Nashville establishment of the time. These long-haired renegades drew inspiration from outside genres such as rock, blues, soul and rockabilly and were the antithesis of their era’s mainstream country music, which strongly skewed conservative and remained creatively stagnant by design.

They were subversive and radical upstarts back then and fully canonized heroes of the genre today.

This progressive movement occurring in country music is a similar paradigm shift. In some circles, living authentically or giving others space to do so makes you an outlaw. But just like their hippie forefathers, these artists are dedicated to making country music accessible for everyone, no permission required.

The Vandoliers perform at Friendsgiving at the Longhorn Ballroom in November 2023.

Carly Gravley

The Vandoliers can’t be anything but true to themselves. After all, that’s what they believe country music is all about.

“It rewards authenticity,” Fleming says of the genre. “That’s what people want out of these songs. Whether you’re listening to Willie Nelson or Johnny Cash, the old school, or listening to new guys like Charley Crockett and the Turnpike Troubadours, the thing that you’re being attracted to is their story and their vulnerability. And when you get into the realm of talking and writing and performing like that, you’re not going to make everybody happy.”

That appreciation for the authentic is what unites country fans across the political spectrum. The stories and worlds created in these songs feel so down-to-earth and tangible that the listener feels like they’re having a conversation with a friend or neighbor. Progressive artists still capture this feeling, but with the awareness that not all of our neighbors are straight and white.

Ross connects with his audience both with his authenticity and by being the role model he wishes he had growing up.

“If I had someone like me growing up that was doing the stuff I’m doing now, it might’ve made things a little bit easier for me,” Ross says. “I want to be able to be that person for somebody who is, I don’t know, 15 years old and still trying to figure themselves out.”

As for the Vandoliers, creating music and live experiences that are diverse and accepting is second nature at this point.

“You should be able to wear a cowboy hat and Converse,” says Fleming, calling back to his punk-to-country crossover. “You should be able to be gay and go to a country show. You should be able to be trans and put on a nice dress and not feel like you’ll get beat up or made fun of when you go to the show.”

“Would 100 percent wear a dress again to keep douchebags out of our show,” Graves says.