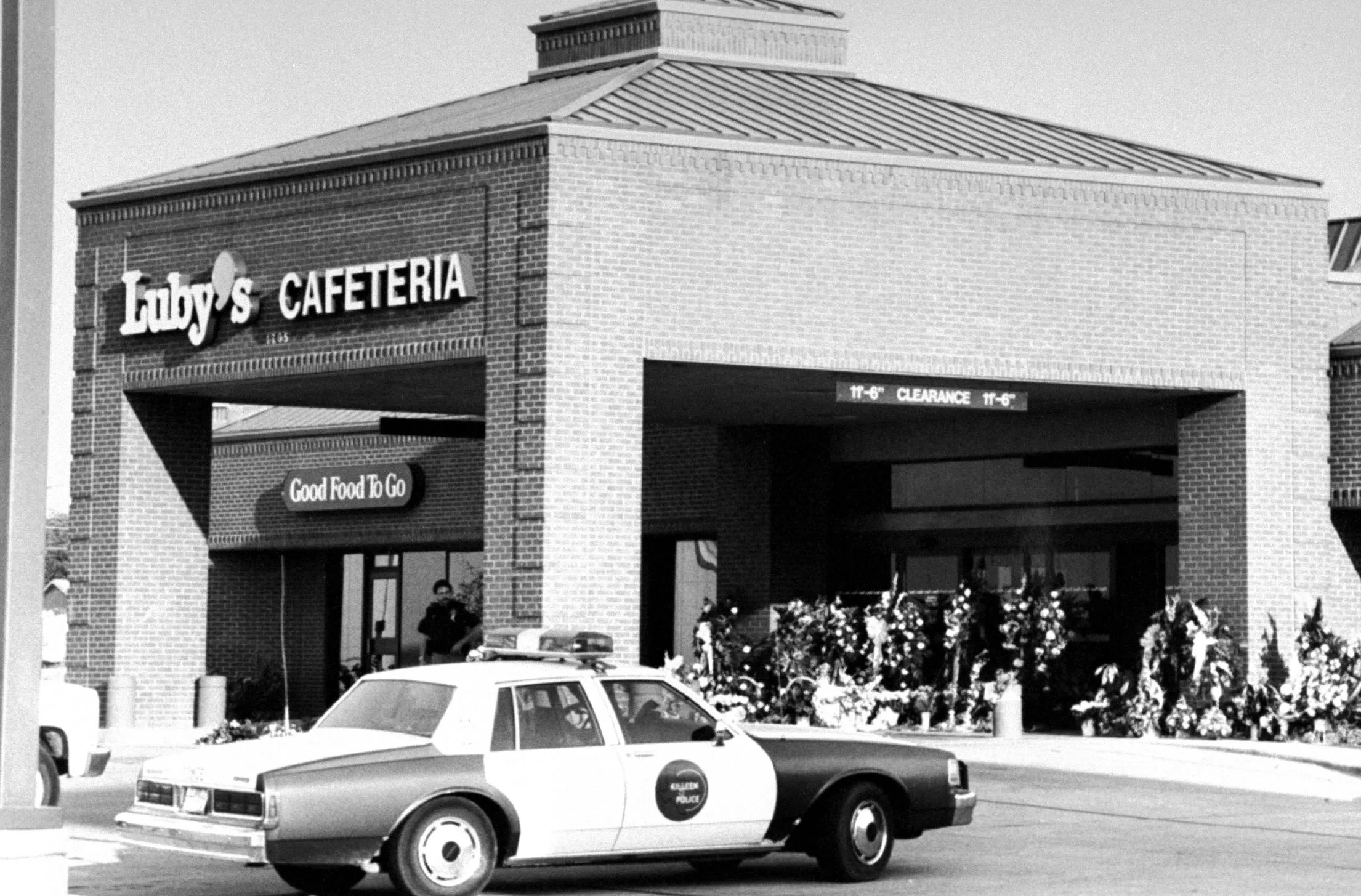

Mark Perlstein/Getty Images

Audio By Carbonatix

The man and his weapons were both from out of town. That’s one of the first things many Killeen residents, both past and present, will remind you: He wasn’t one of them.

George Hennard was from Pennsylvania, and he was living in Belton, a city about 25 minutes away from Killeen, when he committed what was then the largest mass shooting in U.S. history. On that fateful morning, he stopped for a big breakfast: a sausage-and-biscuit sandwich, a candy bar and doughnuts, all washed down with orange juice. It was Oct. 16, 1991, Boss’s Day.

It would be easy to recap the grisly details of that day, to detail how Hennard, a 35-year-old man recently booted from the Merchant Marine, drove his blue 1987 Ford Ranger pickup through a plate-glass window of one of Killeen’s most popular lunch spots and then opened fire. But this is not only a story about murder, nor is it only a story about the man neighbors called “standoffish” but “friendly,” foreshadowing the cases of often lonely, murderous men who would carry out mass shootings over the years that followed. This is also a story about what comes after, when the cameramen have long since left and the town is left to pick up the pieces. It’s about shadows, about how a day that began with a junk food breakfast casts darkness that shapes lives decades later.

More than 30 years after Hennard killed nearly two dozen men and women, the people of Killeen – and, in some respects, all Texans – are still dealing with the emotional, moral and legal aftermath.

“No community is, or could ever be, prepared for the tragedy which struck Killeen on Oct. 16, 1991,” the mayor and city council wrote in a “thank you” to first responders displayed in the Killeen Daily Herald later that year. “Our hope and prayers are that a similar event will never again occur in any community.”

**

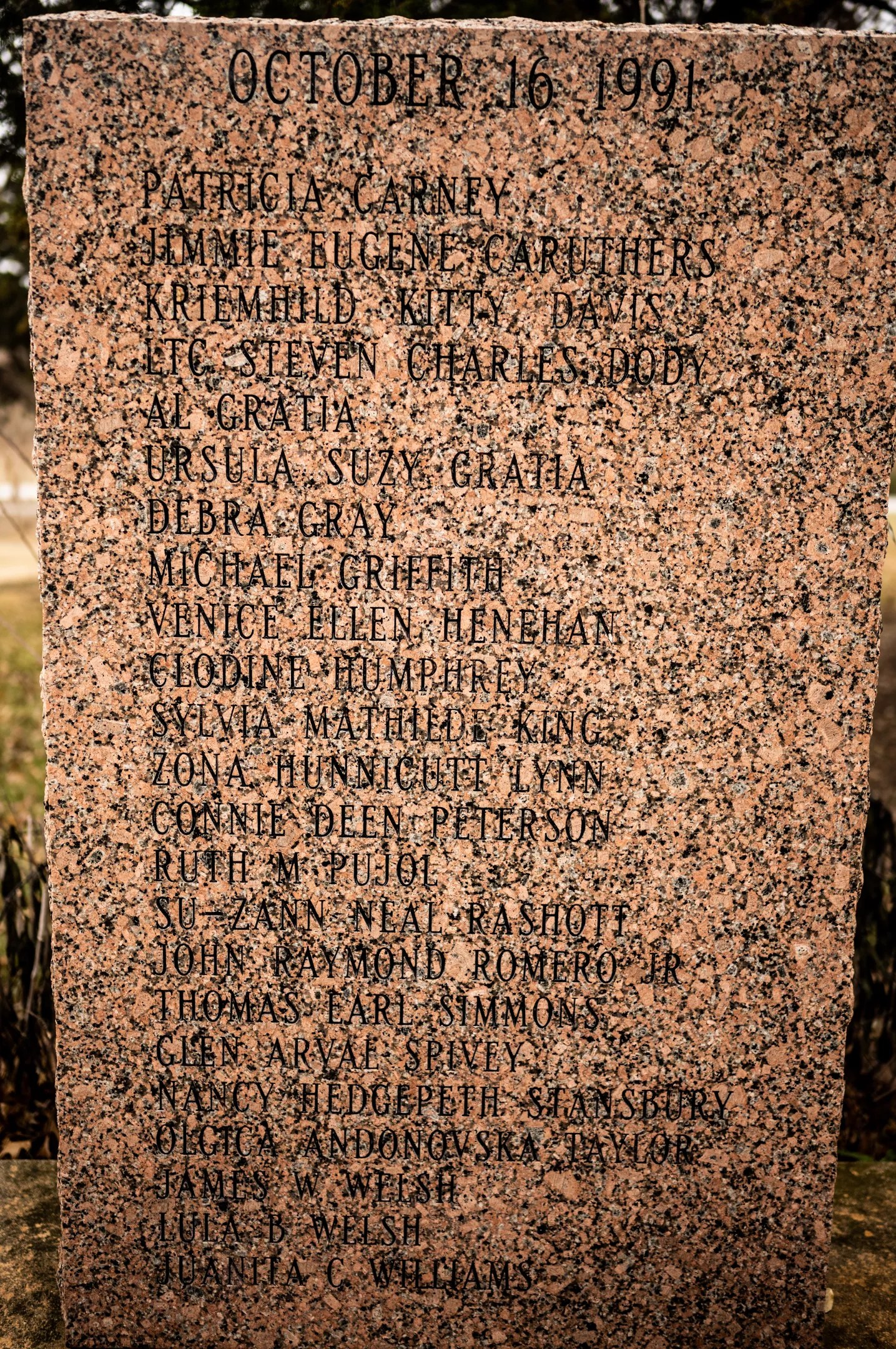

The names of the shooting victims in the Luby’s cafeteria killing.

Mike Brooks

In early December, amid a mass of holiday shoppers at a Killeen mall, a man wearing a sweatshirt, face mask and white beanie fired a gun 10 times, sending one victim to the hospital. A few weeks later, police were still searching for answers: Was this a targeted action or an attempted mass shooting?

“My concern is that a man pointed a handgun at another person and pulled the trigger 10 times, so he meant to kill that person,” police Chief Charles Kimble told local news. “That’s a dangerous person.”

In August, a TikTok video captured what sounds like a gunfight between police and a shooter at the Killeen strip club Naked City.

“That boy shooting, boy, that’s some big shit,” the TikToker told his followers as bullets ricocheted nearby. He is smiling at first. Then, when a man approaches the shooting off-camera, the videographer’s mood turns somber.

“Hey bro, get down,” he tells the man. “That’s some big shit.”

“I got family back there,” the man replies.

That man is still repeating the same words (“I got family, I got family”) as the videographer starts to run, the TikTok still rolling. A day later, the video went viral.

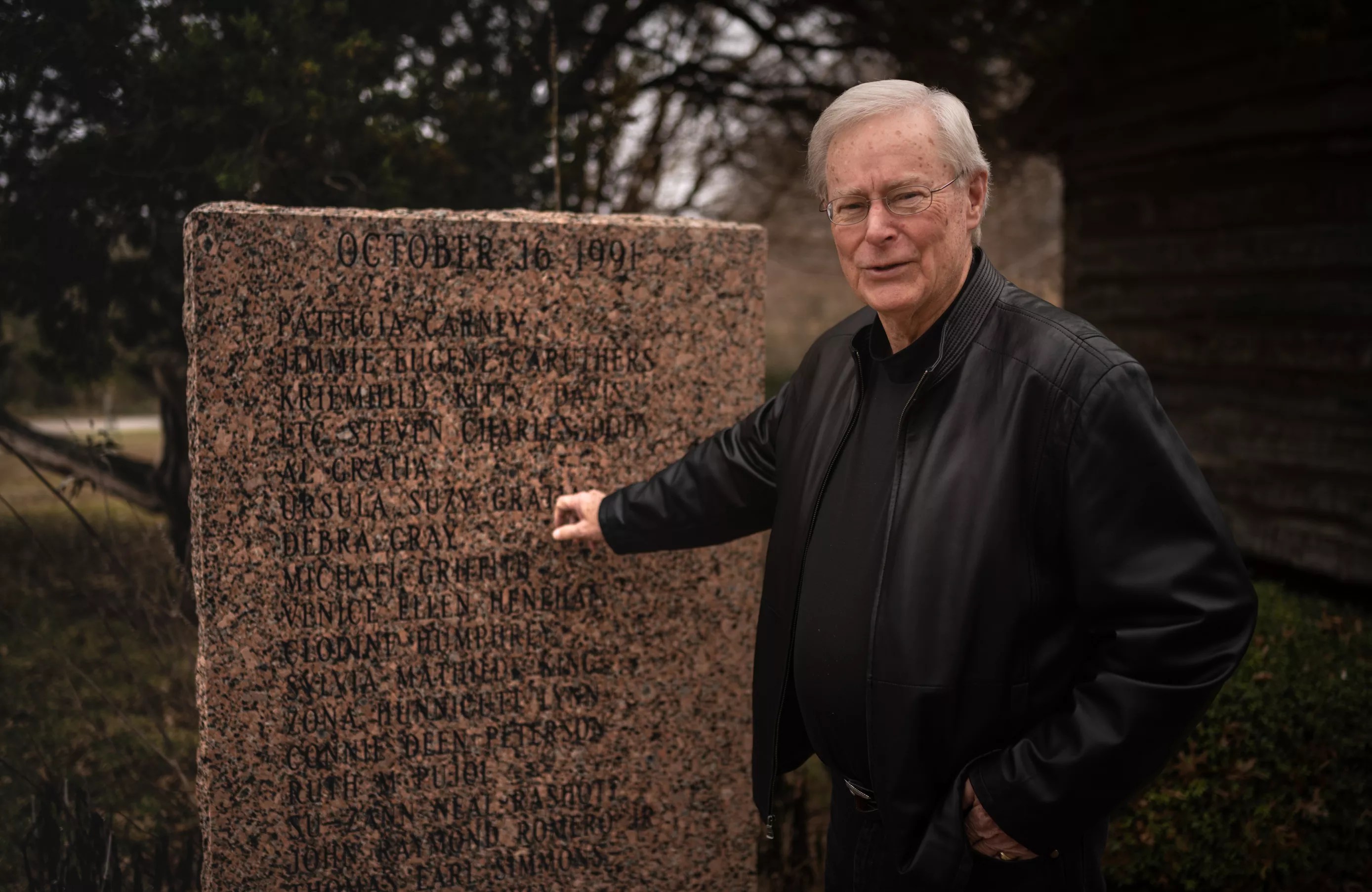

Those shootings were still fresh when the Observer phoned pastor Jimmy Towers to talk about what he saw, heard and felt in October 1991. Towers, now 78, has the kind of temperament and timbre you’d expect from a veteran Baptist pastor. At once comforting and patrician, his Texas drawl trickles like molasses as he tells stories brimming with asides, anecdotes and spiritual musings.

Early on in the conversation, he acknowledges his city’s grim record of tragedies – “We’ve had our share,” he says – but is quick to point out Killeen’s resilience.

“There’s a sense that Killeen has the resilience because of life experience with Fort Hood,” he says. It’s not uncommon for Killeen residents to travel to the airport to greet caskets carrying fallen soldiers coming home to the Army’s top training spot for heavy forces.

“The community’s resilience through the years of life, death and tragedy has helped us handle it well,” Towers says.

In January 2022, Pastor Jimmy Towers stands in front of the memorial to the 1991 shooting in Killeen, Texas.

Mike Brooks

In October 1991, Towers was the new pastor at First Baptist and a recent transplant from San Antonio. When Hennard crashed through the Luby’s entrance around 12:45 p.m., Towers was in a Rotary Club meeting in the hotel next door. He didn’t know anything was wrong until he left for a funeral. A horde of people had gathered in the Luby’s parking lot, and a cop Towers knew was standing nearby. When the cop told the pastor what happened, Towers’ first thought was of his wife. The couple occasionally dined at Luby’s, and he didn’t know if she was there when Hennard arrived. He raced home, opened the door and there she was: safe.

Back at Luby’s, Al Morris had just concluded a gunfight that sent his mind flying back to the jungles of Vietnam. Morris, a Killeen detective, spent a year as a crew chief mechanic and door gunner on a Huey helicopter. He and his men were shot down five times, and on one occasion, a bullet passed through Morris’ shirt.

“I was there for a year, and a lot of that flashed back,” Morris told the Herald. “The first month after Luby’s, I had a constant VCR in my head, and all I could see were bodies [lying] on the floor.”

Few people can relate to what Morris endured. The Vietnam vet engaged in a violent shootout with a man who, he would later learn, had killed 23 of Morris’ neighbors. It only ended when Hennard, wounded by bullets from Morris and fellow officer Ken Olson, took his own life.

But the events of Oct. 16 lingered with everyone who was there and countless folks who weren’t.

“Simply by definition, mass shootings are more likely to trigger difficulties with beliefs that most of us have, including that we live in a just world, and that if we make good decisions, we’ll be safe,” says Laura Wilson, a professor of psychology at the University of Mary Washington in Virginia. Research also suggests that mass shootings create lasting trauma. Dr. Lynsey Miron, who survived a mass shooting on her college campus in 2008, found that about 12% of survivors report persistent post-traumatic stress disorder. That’s a higher percentage than the average prevalence of PTSD among trauma survivors as a whole.

Towers says he counseled one detective for at least six months after the shooting. Even three decades later, his work is far from finished.

“For me, I’m still dealing with the PTSD to a number of people,” he says.

Even though he was new to the community, Towers played a big role in the aftermath of the murders. When the media storm inevitably arrived in Killeen that October, Towers tried to defuse what he says was a tense situation. The town of just over 60,000 wasn’t accustomed to that kind of attention, and some of Towers’ parishioners didn’t enjoy sharing the pews with reporters.

Yet where some saw inconvenience or morbid curiosity, Towers saw opportunity. He invited the major networks to film his Sunday service provided they didn’t interrupt with too much movement, and he agreed to let CBS’ Dan Rather shadow him for a couple days.

“We are being presented to the world as a place of tragedy,” Towers told his flock. This was a chance to show them they are more than that.

At one point during his time with Rather, the legendary anchor asked Towers if his faith was ever shaken by something like this. They were in the church courtyard, and the cameras were rolling.

“Yes, it is,” Towers replied. But the editor cut out the rest of his response.

“If they had shown the rest of what I said, you would have seen me say something like, ‘It’s also times like these that strengthen my faith,'” he says. Then Towers turns to scripture, citing a passage from 1 Peter that reads, in full, “These trials are only to test your faith, to see whether or not it is strong and pure. It is being tested as fire tests gold and purifies it-and your faith is far more precious to God than mere gold. So if your faith remains strong after being tried in the test tube of fiery trials, it will bring you much praise and glory and honor on the day of his return.”

Towers believes those words will tell you a lot about Killeen. It’s a strong place, he says, that has retained its essential resiliency through multiple shootings and recent turmoil at Fort Hood.

“When the challenges come, we’ve been exposed to and trained by people who say, ‘meet the challenge'” he says. “But are there emotional scars? You bet. When I go to lunch with people, they still don’t want to sit with their back to the door of the restaurant.”

This is something you’ll hear from a lot of Killeen survivors: They like to eat facing the entrance. According to research, it’s a classic trauma response. You want to exert what control you can. You don’t want to be blindsided. Not again.

Tommy Vaughn is one of those survivors. A few years ago, he gave a lengthy interview to Reporting Texas. In the piece, Vaughn talked about how, when he goes out dining, he carefully selects the seat that seems safest. He talked about saving lives that day in Luby’s, but he denied that he’s a “hero.”

Vaughn, who was 28 at the time of the shooting, is still employed at the same Belton repair shop where he worked in the early 1990s. But a lot else has changed since he saved numerous lives on that day. He met Oprah. He met Dan Quayle. He shed about 130 pounds. And about six years ago, he reunited with one of the women who is probably alive because of him.

That woman, Suzanna Gratia Hupp, has been one of the country’s foremost Second Amendment advocates for the last quarter century. Whereas Towers’ voice is soft, Hupp, who shares his Texas drawl, is often emphatic and brimming with passion.

“It’s funny, because as much as I do Second Amendment stuff, I am not a gun person,” Hupp tells the Observer. “I am not a hunter. I’m not into guns. Some people might argue that point, but they’d be wrong. I don’t care about guns.”

On Oct. 16, 1991, she and her parents went to lunch.

**

Suzanna Gratia Hupp lost both of her parents in the Luby’s shooting in 1991.

Mike Brooks

On the way to the restaurant, the main topic of discussion was her parents’ upcoming 50-year anniversary, even though it was three years off. They didn’t want anything extravagant for the celebration; that wasn’t their style. Plus, they still had a few years to plan. But a milestone this big was top-of-mind, and the couple agreed that some kind of family celebration was a must.

Hupp describes her mother, Ursula “Suzy” Gratia, as a hardworking woman who put in a lot of hours at the office and at home. Suzy was an executive secretary at Boeing, where her solid editing skills would help her fix whatever the engineers wrote. She used those skills at home, too. Her husband, Al, was a happy retiree who could either be found on the golf course or working on his forthcoming history book, and Suzy lent her editorial eye whenever she could. In her spare time, Suzy also made her family clothes.

On that day in October, the couple were spending time with Suzanna at one of the family’s go-to restaurants. Hupp lived in Copperas Cove at the time, but Killeen was just 15 minutes away. “Back then, there weren’t many places to eat,” Hupp recalls. Plus, she knew the manager at Luby’s.

When the trio arrived for lunch, Hupp left her handgun in the car. Concealed carry was still illegal at the time, and for several months she had been worrying about the prospect of getting caught with the weapon and losing her chiropractor license. Three decades later, she is still angry about that decision. If she had her weapon, she argues, then she could have stopped Hennard.

“I was furious at myself for having obeyed a stupid-ass law that resulted in a lot of deaths, my parents included,” she told the Observer.

The family was wrapping up their meal when Hennard drove his truck through the glass and started shooting. Once she realized what was happening, Hupp instinctively reached for her purse, where she used to keep her revolver. Then, as she told Texas Monthly six years ago, she remembered the gun was still in her car, “completely useless.”

“Could I have hit the guy?” she asked the magazine reporter, running through a list of possible questions. “He was 15 feet from me. He was up. Everybody in the restaurant was down. I’ve hit much smaller targets at much greater distances. Was I completely prepared to do it? Absolutely. Could my gun have jammed? It’s a revolver, so it’s possible, but is it likely? Could I have missed? Yeah, it’s possible. But the one thing nobody can argue with is that it would have changed the odds.”

Suzy and Al were shot and killed by Hennard. Hupp was one of the many people saved by Vaughn, the mechanic, when he flung himself through one of the restaurant’s glass windows.

“Is there anyone I can get for you?” the psychiatrist asked Hupp after the shooting. The survivors were gathered in the hotel Towers had left a couple hours earlier, and some people from Fort Hood and the local hospital were on hand to help out. Hupp’s boyfriend was in the service, and she told the psychiatrist she’d like to see him. Calls were made, and soon enough, her boyfriend was driven from San Antonio’s Camp Bullis to Killeen. Hupp, her boyfriend, her siblings and their spouses gathered to grieve and deliberate.

“We started getting a lot of calls from the press, and your first reaction is to go, ‘Oh, hell no!'” Hupp says. “But we spoke as a family, and we decided we’d speak to the press.”

One of Hupp’s first calls was with a reporter from The Associated Press. She told them she wasn’t mad at the shooter, because you can’t be mad at a “rabid dog.” But she was mad at her legislators, who she says prevented her from defending herself and her family.

“You can’t help [it], but every time you close your eyes, you relive it,” she says, recounting the seething anger she felt on the phone with AP. “And then you relive it with a gun in your hand. What if?”

According to Dr. Robert Spitzer, a political science professor at SUNY Cortland and the author of five books on gun control, the Killeen shooting is a key moment in the history of modern gun laws. Paired with a 1989 schoolyard shooting in Stockton, California, Hennard’s murders created a heightened focus on gun rights. There was a trend in the 1990s, Spitzer says, when federal gun laws were becoming stricter while state laws were becoming more lax.

Democrats and Republicans alike seized on the Killeen shooting to make their arguments. The shooting was name-checked in Bill Clinton’s gun control platform when he won the presidency a year later. At that point, an assault weapons ban proposed by Democratic Sen. Chuck Schumer of New York had already failed miserably in the House, where Schumer was serving at the time. Clinton’s election gave gun control advocates some hope, even if the narrative on the ground in Texas was already going in the other direction.

“Maybe somebody could have stopped that crazy guy in there had there been an armed citizen,” Dr. Jim Brown, a spokesman for the Texas Rifle Association, said shortly after the shooting. “Maybe then he wouldn’t have gotten so far.”

The local police chief made similar remarks while suggesting that citizens ought to be able to carry guns for their own protection. Hupp also entered the fray, sharing her story throughout the country and testifying in support of concealed carry laws.

“I’ve been on every slime-bag talk show you can imagine, and some of them twice,” she told Texas Monthly. “I would always wash my hands well after I finished, but I think I’m glad I did them. I testified in a couple dozen states and hopefully helped to change a vote or two.”

She also ran for the Texas Legislature and won five terms, serving from 1997 through 2006. She continued to advocate for gun rights, often proposing laws centered on who was eligible to carry a weapon, where they could carry it and who had to know.

Dr. Gregg Lee Carter, a sociologist who, like Spitzer, has written extensively on gun control, cites Hupp as a key player in the “rallying cry” for gun rights created by the Luby’s shooting.

“It is relatively uncommon for either side in the gun control debate to have an event that so clearly supports their argument and a spokesperson who can clearly and persuasively articulate their position in personal terms,” Carter wrote.

Before the Killeen shooting, the Texas Senate had passed a bill that allowed trained, licensed adults to obtain concealed-carry permits for handguns. As Carter recounts in his book, Guns in American Society, there were enough votes to pass the bill on the floor of the Texas House. The House Rules Committee, “acting in secret,” Carter wrote, killed the bill by preventing it from reaching the House floor for a vote.

“Even if the bill had passed the legislature, however, Governor Ann Richards would have vetoed it, as she did when a handgun-carry bill passed the next legislature,” the sociologist writes. “That veto played a major role in Richards’ 1994 election defeat by Republican George W. Bush.”

A year later, Bush signed a concealed carry bill nearly identical to the one vetoed by Richards. Like Clinton’s push for an assault weapons ban, Bush’s position on concealed carry laws was a key part of his campaign. It was also wildly popular in Texas. As a Washington Post story said in 2000, “in the five years since Gov. George W. Bush took office, the concept of an armed citizenry as a deterrent to crime has gained a firm hold in Texas.” If you ask Spitzer, though, that concept has roots that go back much further than the Bush era.

“America has long held a mythological view of our past, especially our frontier past,” he told the Observer. “The mythology of the West, the gunslinger and the cowboy began to emerge while it was happening, with people writing novels, newspaper writing and Samuel Colt, who was a genius of marketing.”

Colt was the inventor and businessman best known for the mass production and sale of revolvers. The irony, Spitzer says, is that his biggest buyers weren’t ranchers. Rather, they were East Coast denizens enthralled by cowboy mythology.

Spitzer adds that there is a direct link between that mythology and the “armed citizenry” or “good guy with a gun” narrative that gained ground in Texas after the Killeen shooting. The professor says both this narrative and its mythological underpinnings don’t hold up under scrutiny. “At the turn of the 20th century, strict gun laws were the norm,” he explains. “The idea that average people carried guns and that’s how they protected themselves is not true at all.”

Likewise, he adds, “the idea that a good guy with a gun can save the day is part of the American ethos, but there’s a tiny sliver of evidence to show that’s the case.”

Indeed, numerous studies indicate that concealed carry handgun laws actually precede a rise in violent crime. A 2019 study published in the British Medical Journal revealed that states with “more relaxed” gun laws experience a higher rate of mass shootings. (Four of the 10 deadliest mass shootings since 1949 have happened in Texas.)

These studies appear to have had little to no impact on public opinion.

In recent years, Killeen survivors like Morris, the detective, have expressed support for more gun accessibility, telling the Killeen Daily Herald in 2021, “There’s a lot of talk these days about gun control. But maybe if more people had a gun there at Luby’s, somebody could have stopped it.”

Even though she is no longer in the Legislature, Hupp continues to appear on podcasts and give interviews in support of more gun accessibility. In September 2019, a month after mass shootings in El Paso, Midland and Odessa, Hupp lobbied Congress for less gun control. These views, while controversial to many, are not as controversial as they may have once been. In March 1991, Gallup polling indicated that 68% of Americans wanted stricter gun laws. Today, that same polling question indicates that only a little over half want stricter laws. Further, in 1991, 43% of Americans believed only policemen should be able to carry guns. Today, fewer than 1 in 5 Americans hold that view.

As state gun laws have become more relaxed, many Americans have become gradually more accepting of guns. “I’m happy and proud to be a little part of that,” Hupp told the Observer, referring to the passage of concealed carry laws. “It makes me feel like there’s some meaning to the deaths of my parents and others.”

In some ways, though, she thinks there is still work to be done.

“One of my real pet peeves, and I have filed bills to this effect, is I think teachers should be allowed to carry,” she says. “The schools are where these creeps go to rack up high body counts.”

When she was interviewed for this story, Hupp said she was worried about her sister, a Texas teacher who was nearing retirement and, like all instructors, is legally barred from having a gun in the classroom.

“She caught her principal and superintendent in the hall and said, ‘What are y’all doing to keep us safe?'” Hupp says. “They told her they put up new security cameras, so my sister laughed and said, ‘That’s great! That way they can watch the rampage from lots of different angles.'”

Hupp laughed a bit, too, then got serious.

“Of course, they didn’t find that funny,” she says. “She wasn’t in the restaurant with us, but she lost her parents. She gets it. They don’t get it. They don’t get it.”

**

Inside the former Luby’s restaurant in Killeen.

Mike Brooks

Historian María Esther Hammack has said there is a “collective amnesia” after mass shootings. In her view, this “mass forgetting” represents “both intentional and subconscious healing for people – a way to desensitize or detach ourselves from the pain and the knowledge of such atrocities.”

“What is interesting – and incredibly telling of how we remember mass shootings and the casualties in their aftermath – is that very few people today actually know about the Luby’s shooting,” she told Reporting Texas.

This may be true for many Americans, and even many Texans. Mass shootings have become seemingly endemic, and in 2014, shortly after then President Barack Obama remarked that such violence was “becoming the norm,” Harvard research showed that the rate of mass shootings had tripled since 2011. Ten years later, after the killings in Sutherland Springs, Santa Fe and El Paso, it’s common to read and hear stories about “compassion fatigue” or “psychic numbing.” The frequency of mass shootings is making some people too anxious or depressed to carry on with their lives in a “normal” fashion, while others are becoming desensitized.

In Killeen, Towers refers to the Luby’s shooting as an “emotional remembrance” that still makes people cautious. Others are still coping with that day.

The day before our conversation, Towers was at lunch with one of the survivors, a woman we’ll call Joan. According to him, Joan still talks about her encounter with the shooter.

Shortly after firing some rounds while still seated in his pickup, Hennard stepped out of the truck and began pacing the restaurant. By all accounts, his victim selection was random; he’d let a woman escape with her child, then shoot the next person he saw hiding under a table.

Eventually, he reached Joan.

“He pointed the gun at her face,” Towers says, “and pulled the trigger.”

Click. The chamber was empty. Or maybe the gun malfunctioned. At any rate, Joan escaped. “She still hears that click whenever she closes her eyes,” Towers says.

For others, particularly newer Killeen residents (the city’s population has more than doubled since 1991), the shooting is just something they hear about on anniversaries. “There’s very little to remember it by,” Towers says.

The Luby’s is now a Chinese restaurant called Yank Sing, and residents are far more likely to talk about the recent rash of disappearances, suicides and sexual harassment at Fort Hood.

“You hear about Fort Hood more than you do anything else,” says Stephen, a Killeen resident who moved to the area in 2019 and asked not to use his surname. He and his wife often dine at the Yank Sing, and until the 30-year anniversary a few months ago, he had never heard of the Luby’s shooting.

“Family and friends will ask about Fort Hood,” he says, “if they ask about anything.”

Memory aside, the consequences of this 30-year-old shooting still linger.

James Alan Fox, a criminologist at Northeastern University, believes there is a link between Hennard’s murders and the modern-day calls for fewer gun restrictions. He also argues that increased gun controls will have little effect on mass shootings but a significant effect on other types of crime.

“The mass shooters generally are deliberate, determined and will find a way to get a gun no matter what we put in their path,” Fox says. “Now, should we make it more difficult? Yes. But those policies that are proposed in the wake of mass shootings would have the greatest effect on the type of ordinary gun violence we have every day.”

Dallas Police Chief Eddie Garcia has also railed against relaxing gun laws. Last year, he joined the chorus of law enforcement officials who opposed the “constitutional carry” bill Gov. Greg Abbott signed into law in 2021. That law eliminated the requirements for people who carry a handgun, including a background check, four to six hours of training and a shooting safety and proficiency test.

“A minimum level of training is not asking too much for carrying a firearm, and it is consistent with the Second Amendment,” Garcia said at a news conference from the state Capitol last May. He and other law enforcement officials had gathered to state their opposition to the bill that Abbott would make law just a couple months later.

Other leaders on hand, including Doug Griffith of the Houston Police Officers’ Union, emphasized that “constitutional carry” poses a safety issue. Safety issues, he argued, should be bipartisan.

“It makes our job, the job of our men and women, more dangerous,” Garcia said. “Gun owners have a duty to ensure that their firearms are handled safely and a duty to know applicable laws. The licensing process is the best way to make sure this message is conveyed.”

Meanwhile, the people who survived the Luby’s shooting have carried on. Those who still live in the area occasionally cross paths.

“It still happens,” Hupp says. “Every once in a while, I’ll run into someone who was there.”

She was speaking at an event in Temple some six years ago when a man walked up to her. It was Vaughn, the same guy who flung his body through the glass, saving her and many others.

“And God love him, he was tearing up and asking to give me a hug,” Hupp says. “People’s lives are so intertwined. You never know how, or what the ripple effects are.”

Towers, who continues to console and counsel those affected by the Luby’s shooting, is now the pastor at Lifeway Fellowship in Killeen. He allows people to carry guns into his services but asks that they refrain from open carry so as not to distract the children. For the most part, he says, people have been cordial and respectful of his wishes. “Attitude people really don’t fit in our congregation,” he says. Still, Towers often thinks about safety and security.

After the 2017 shooting at a church in Sutherland Springs, he added some security upgrades to LifeWay Fellowship. Most of them are not plainly visible, he says. Security guards share space with the lighting equipment in the church’s balcony, which sits above the pews and the pulpit from which Towers preaches. One day, the preacher was talking to his brother-in-law, a veteran and marksman, about the church’s security set-up.

“He said, ‘Do the guys upstairs have a long gun?'” Towers recalls. “And I said, ‘Why would you ask that?’ And he said, ‘Well, there’s 100 feet between them and your position on the platform, and if someone comes up to you on the platform, someone with a pistol isn’t gonna be able to do anything.’ And I thought that was interesting.”

Nowadays, Towers says, the people he talks to in Killeen are more worried about COVID-19 than they are about another mass shooting. Yet the pandemic has inspired a surge in gun sales. As reported by The Trace, the National Rifle Association, which helped popularize the “good guy with a gun” narrative, has contributed to that spike in recent gun interest.

“I hope I survive the coronavirus,” says a woman in a 2020 video released by the organization. “That’s up to God. What’s in my control is how I defend myself if things go from bad to worse.”

Killeen was not immune to that rise in gun sales. In the summer of 2020, local gun seller Damon Cross (whose store is called Texas License 2 Carry) told local news he was limiting customers to only two boxes of 9mm ammunition, his most popular product at that time.

“People think that they’re going to be walking outside and they’re going to come across a group of rioters and that they’re going to want to damage their property or break into their homes, and it’s just not true,” Cross said.

Later that year, the Killeen Daily Herald published a story that asked, “Is Killeen losing the war on crime?” The rate of violent crime has gone up in recent years, the story noted, and the mayor was calling for “a united front.” By the following fall, the rate of violent crime had significantly fallen, yet violence was still top-of-mind for the city’s residents. The mall shooting in early December was the latest incident to take over headlines and local news, and the attempted murder cast a pall over the town.

Local parent Jeff Thompson was perturbed by an automated text he received from the mall not long after the shooting.

“It’s a little odd, because I got a text message from the mall today, telling me about some great deals they had, and it kinda seemed a little odd just to keep going on after so many went through this,” he told a news reporter. “You never know when your loved one is going to be trapped in a school, university or a mall and be a victim to someone who’s lost their marbles. Hopefully, we find out the root cause of this is actually, and we tackle it instead of just putting it under the rug again and say it’s another day in Killeen.”

Other Killeen residents were talking about buying a gun for the first time.

“You never know what it’s like until you experience something like that,” a woman named Marguerite Wright, who was in the mall that night, told a local reporter. “People see it on TV, people see it on YouTube, people see it in the news, but it’s different when it happens to you.”