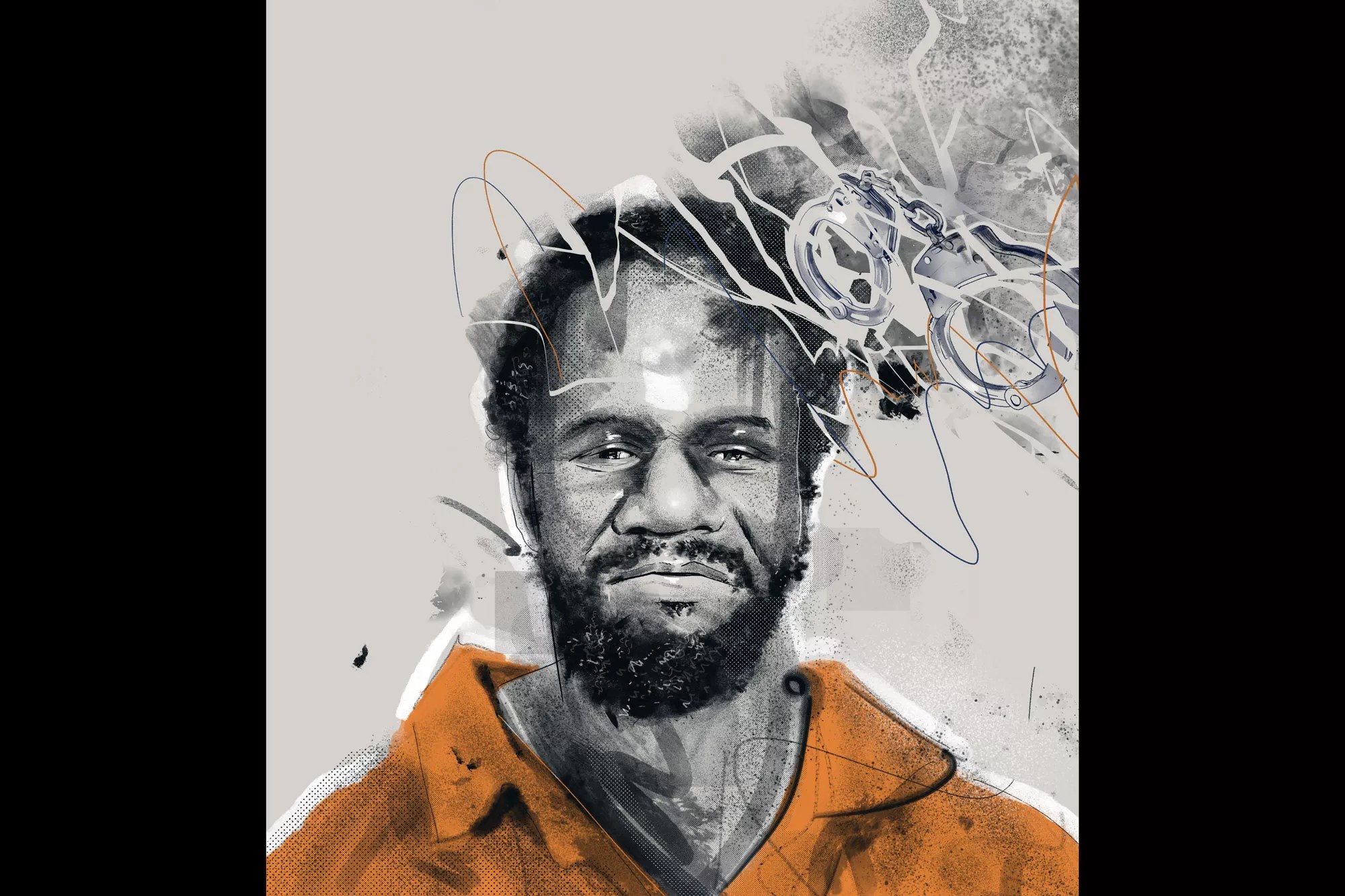

Illustration by John Garrison

Audio By Carbonatix

On a balmy evening last November in Tyler, Enus Lewis finally came undone.

After dark, Lewis left his mother’s house and staggered into oncoming traffic on the busiest road he could find, hoping an oncoming car would kill him.

Months of battling a tidal wave of grief had sharpened Lewis’ schizophrenia. The voices telling him to hurt himself, that others were trying to hurt him, hit a fever pitch. He’d lost his infant son, his lifelong best friend and now his girlfriend of eight years and mother of his children – and it was all too much.

In the months before he stepped into oncoming traffic, Lewis, 39, knew he was unraveling. He showed up at Tyler’s state mental health provider, asking them to admit him to an inpatient psychiatric facility to keep him from killing himself.

Lewis’ mother and friends echoed his pleas, begging the clinicians to see how much his mental state had deteriorated. But they still turned him away.

The Andrews Center, like the 38 other local mental health authorities contracted by the state, operates mobile crisis response teams designed to respond to 911 calls about mental health crises. Their goal is to keep mentally ill people out of jail.

But when 911 callers reported a Black man trying to jump in front of passing cars that November night, police were dispatched instead. For the 40th time since he first sought treatment from the Andrews Center nearly two decades earlier, Lewis wound up in Smith County Jail.

**

Lewis plays with his son.

courtesy Dalila Reynoso

Nationwide, people like Enus Lewis, who live with untreated, chronic and serious mental illness, return to jail or prison more often and suffer far more violence than others while incarcerated. Aiming to avoid locking up mentally ill individuals, public mental health agencies work with police, jails and prisons on a variety of programs designed to redirect them away from jails and toward public mental health services.

In Texas, the Department of Health and Human Services and numerous local private medical care providers work with the Texas Department of Criminal Justice to identify people with mental illness before they’re incarcerated. The hope is to provide treatment and long-term psychiatric care instead.

But since at least 2017, cuts to state funding of these alternative programs and restrictive statewide caps on public mental health services caused Lewis and more than a thousand others like him to be dropped from or denied critical mental health treatment after coming into contact with the criminal justice system.

In 2014, the year before Sandra Bland reportedly died by suicide in Waller County Jail, Texas earmarked $319.6 million in total for diverting people from incarceration and caring for “special needs offenders”, meaning those diagnosed with severe mental illness or intellectual disability.

Bland, who was Black, committed suicide after her arrest by a white Department of Public Safety trooper during a dubious traffic stop. Her death prompted a slew of mental health screening and in-custody care policies and $16-million plus boost for diversion and long-term psychiatric treatment. By 2017, the rate of complaints to the state’s top jail inspectors related to mental or medical care had decreased by 8%.

But in 2017, following two years’ of marked improvement, lawmakers slashed mental health treatment programs’ funding by more than $63 million over the next two years. TDCJ and the Texas Correctional Office on Offenders with Medical or Mental Impairments asked for $35 million of it back in 2019, citing the increasing numbers of people needing psychiatric treatment in their care. Lawmakers responded by cutting treatment programs’ funding by an additional $600,000, and setting what advocates say is an unreasonably low cap on funds to pay for chronically ill patients’ psychiatric medications.

As a result of multiple years of funding cuts, at least 1,320 justice-involved people statewide were dropped from or denied access to long-term counseling, jail diversion and long-term psychiatric care between FY2019 and 2020 alone, according to state data.

“We’re creating a landscape where there’s no choice but to funnel people into the criminal punishment system.” – Krishnaveni Gundu, Texas Jail Project

In Smith County, where Lewis lives, the effects of these restrictions are stark. According to data obtained by the Observer, the Andrews Center provided care for individuals diverted from Smith County Jail 398 times in 2018, 490 times in 2019 and 131 times in 2020.

Today, Texas has the second largest county jail population in the U.S. and ranks 40th in state spending on mental healthcare. Advocates and top state watchdogs meanwhile say treatment for the nearly 20,000 people with mental illnesses currently held in Texas county jails has reached a crisis point.

Krishnaveni Gundu, co-founder and CEO of the Texas Jail Project, said she has observed an increase in denials issued by local mental health authorities. “We’re creating a landscape where there’s no choice but to funnel people into the criminal punishment system,” she said.

In a recent meeting of the Judicial Commission on Mental Health, the executive director of the Texas Commission on Jail Standards, the state’s county jail watchdog, decried the current state of mental health services in county jails. “If we can’t have more of an impact and prevent our county jails from being the de facto mental institutions of our time,” he said, “then I’m afraid we’ll be like Nero, watching Rome burn.”

**

Lewis with his daughter at a dance

courtesy Dalila Reynoso

Hurtling along a lonely stretch of Interstate 20 between Tyler and Dallas one day in late 2000, Enus Lewis was jolted back to reality. “I was driving up to Dallas, thinking that I’m going to go see my son,” he said. “But I realized, I’m just driving to nowhere.”

In December 1999, Lewis noticed that his 13-month-old son Jared was struggling to breathe. After checking Jared into Dallas Children’s Medical Center, doctors told Lewis that his son had been born with an enlarged heart.

For some weeks after, Lewis drove back and forth with Jared’s mother between Dallas and Tyler to visit Jared in the hospital. During one visit, Jared’s condition started to plummet. As he watched doctors working on Jared with increasing urgency, Lewis couldn’t quite believe what was happening.

Within hours, Jared was gone. Even as he and Jared’s mother wept in the hospital waiting room, he couldn’t fully accept it. “It was still just unbelief, just unbelief,” he said.

In the two years that followed, Lewis said his mental state declined rapidly. He grieved, numbing himself with drugs and alcohol. But something else “just wasn’t right with me,” Lewis recalled.

He found his mind racing with voices he wasn’t sure were real. He started noticing large gaps in his memory of day to day events. He felt increasingly suicidal. More than once, he’d started the drive to Dallas to see his son in the hospital and only recalled that his son had already died once he was well on his way.

By 2002, Lewis had grown desperate for help. “I just told my mom, ‘Mom, something’s just not right with me.'” They went together to the Andrews Center, where Lewis tried to explain his background: the trauma of son’s death, intense mood swings, hearing voices and an older brother diagnosed with both schizophrenia and bipolar disorder (both diseases have genetic components).

But the clinician, Lewis said, barely listened to him. “She just blew me off, and said, ‘Well you’ll be fine,'” he said. He received no further screening or care options after this initial assessment.

That day, Lewis left without much hope. He figured he had to weather what has since been diagnosed as schizophrenia and bipolar disorder without medication or outside therapy. He’d just been turned away by the public provider and didn’t have the money to pay a psychiatrist. “I kind of just figured OK, this is what my life is now, so I just have to deal with it,'” he said.

For the next nine or so years, Lewis worked on and off at warehouses and on construction sites through a local temp agency. More and more, he depended on drugs and alcohol to get through the day. He landed back in Smith County Jail at a dozen times between 2002 and 2007 alone on public intoxication and possession charges, records show. Every time he was booked, Lewis told jailers about his mental health problems, and asked to see the jail’s in-house mental health provider. He was denied every time, he said.

Jared’s death plagued him. “I’d just remember him looking back and forth from me to his mom, from me to his mom, like saying goodbye, like he knew it was his time,” Lewis recalled. Year after year, as the anniversary of Jared’s death approached, “I’d just lose it. And I wind up in the county jail.”

**

In 2007, Texas senators passed landmark legislation aimed at keeping people with mental illness out of jails by identifying them during booking.

The law established a statewide data sharing system that requires jail employees to check whether an individual being booked has previously been hospitalized in a state psychiatric facility or received services or assessments from their local mental health authority before.

If the individual has had contact with either the local mental health authority or the state psychiatric hospital, jail employees must contact the local mental health authority in their county to link the individual to treatment resources. The sheriff must also notify a county judge.

County jail staff are also required by law to screen all incoming detainees for mental illness by completing a standardized screening form issued by the state’s jail watchdog agency. If a detainee shows any signs they may attempt suicide, or if the arresting officer has reason to believe they are suicidal, jail employees must immediately notify their supervisor, a local magistrate and the mental health authority.

The way mental health authorities are involved in screening, flagging and diversion processes looks different from one county to the next. In Dallas County, which is served by the North Texas Behavioral Health Authority, “care coordinators” are embedded in the jail, said Jessica Martinez, the authority’s chief clinical officer. “Those care coordinators are able to provide information to the jail staff about the client, do the crisis assessments, and we also get them connected to care,” Martinez said.

“I’d just lose it. And I wind up in the county jail.” – Enus Lewis

The authority embeds care coordinators in the six county jails it serves, including Dallas. In the rural counties like Van Zandt, Henderson and Smith that the Andrews Center serves, though, mental health services in the jail are often less robust.

“Because this is a rural area, some of our rural folks don’t have a lot of access to psychiatric care for their inmates,” said Kathy Wakefield, director of forensics at the Andrews Center. “So we go in, and we do the assessments.”

The number of patients the Andrews Center can serve is also restricted by a cap that is mandated by the state. Andrews Center division director Laura Newsome said the Center is typically “serving over the target given to us by the state.”

The Andrews Center has never exceeded the state’s cap so much so that it was sanctioned, Newsome clarified.

Smith County, because it is the largest of the five the center serves, contracts with another third-party medical provider that conducts mental health screenings inside the Smith County Jail, Wakefield said.

Turn Key Health Clinics, an Oklahoma City-based corrections healthcare provider, secured a $2.86 million annual contract in February 2021 to provide medical services to those held in Smith County Jail. Under its contract with Turn Key, the Smith County Jail has expanded its mental health and medical coverage for those in custody, Smith County Sheriff Larry Smith told ABC’s Tyler affiliate, KLTV.

Turn Key is facing at least eight separate lawsuits filed by families of people who were seriously injured or died in Oklahoma county jails following alleged medical negligence by Turn Key staff. (The Smith County Sheriff’s Office didn’t respond to inquiries as to why it chose to contract with Turn Key.)

**

Lewis and his son work on a car together.

courtesy Dalila Reynoso

At first, Rokesha Williams thought Lewis was just talking on the phone when they were hanging out at her place last summer.

Williams, Lewis’ ex-girlfriend (“We’ve always remained close, close friends,” she said), was providing solace: a month or so earlier, a former girlfriend, with whom Lewis had been for some eight years, had died of COVID-19.

Not long after arriving at her place one afternoon last June, though, Lewis had jumped up and hustled out the front door. She could hear him talking to someone outside.

When she opened the door to check on him she found him locked in a heated argument. But there was no one else there.

“Just come inside, lie down,” she told Lewis, trying to calm him.

“That next morning, when I took him to his mom’s house, that’s when I really realized, oh, he’s having a mental breakdown,” said Williams.

She was all too familiar with Lewis’ struggles with schizophrenia by that time.

They’d met in 2011, and quickly connected as friends.

“He’s just very kindhearted. Doesn’t talk mean, or talk down, he tries to encourage people,” she said. Within six months, they were dating.

“When we first met, I didn’t really experience or see any of that with his mental health,” said Williams. It was only later on in the relationship that she started seeing Lewis doing “little strange things” such as talking to an empty room or staring blankly into space for long periods. “Then he would kind of just snap out of it, and it’d be fine, it’d go away,” she said.

For the most part, though, they had a good relationship.

“He’s a cleaner,” she said. “When he was home, the house was spotless. Like he’s sweeping all the way into the corners, clean, clean, clean. When he’s not himself, though, he’d just sit there. Even if he saw me cleaning. That’s how I would know he was not himself.”

Lewis was still drinking a lot and using drugs, “but he’d do it behind my back, never in front of me,” said Williams. “Not until here recently, when it really has gotten worse.”

In 2013, Lewis and Williams had twins. Soon after that, though, their romantic relationship fell apart.

Lewis moved out; the twins stayed with Williams but still saw their dad often. “Like I said, we’ve always remained friends, and when he’s around, we just do like one big happy family,” she explained.

Soon after, Lewis was in a new relationship with a woman named Feonca, working temp warehouse gigs, hanging out most days with his best friend Tori.

Still, Williams remembers Lewis’ mental health getting worse in the years after they split; more conversations with no one, more staring off at nothing.

She also remembers his seeking help year after year from the Andrews Center and being vexed when he was declined time after time.

“He would tell me, ‘I need help, I need help, I need help,'” she said. “A lot of people don’t ask for it. And here’s a person who’s asking, and asking and acting out for it, and not getting [any help]. That kind of puzzled me.”

In the five years after they split, Lewis was booked into Smith County Jail and administered a mental health screening 11 times. Williams said he would show up at the Andrews Center after being released, often with his mother alongside him to vouch for the truth and severity of his symptoms.

Five days before the anniversary of Jared’s death in 2018, Lewis was stopped by Tyler police officers for public intoxication. The interaction ended with officers charging Lewis with assault on a peace officer. Later, he was convicted and sentenced to two years in state prison.

Then Tori suddenly died. When Lewis was released on parole in August 2019, “Once again, I went back to Mom and said, ‘Something’s going on, something’s not right,'” he said. They returned to the Andrews Center, but yet again he left without treatment, he said.

“He really hadn’t just fully grieved over his son passing, then after losing his best friend, that he was with every single day, that’s when his mental issues really kicked in,” Williams said.

Lewis continued falling apart, rocked by Tori’s loss. Then one day last summer, Feonca came home from dialysis, coughing and shaking. Within days, she was dead.

**

Lewis and his longtime friend Dalila Reynoso

courtesy Dalila Reynoso

Lewis’ mother knew her son was in crisis when Rokesha Williams dropped him off at her house that morning last June. She got him in the car and sped off for help. This time, she decided she’d had enough of the Andrews Center and brought Lewis straight to the inpatient mental health crisis unit at the University of Texas-Tyler.

At UT Tyler, Lewis was finally diagnosed: bipolar II and paranoid schizophrenia, the same as his brother.

He left after a week, new medications in hand. But they were far from enough. For the next four months, both he and his mother begged the Andrews Center to commit him to an extended inpatient psychiatric hospital, both fearing he would kill himself without it.

Lewis was never admitted to any emergency psychiatric facility after he left UT Tyler. When police apprehended him attempting to throw himself into oncoming traffic that November night, the officers didn’t divert Lewis to the Andrews Center or any other psychiatric facility. Instead, they carted him straight to Smith County Jail and booked for allegedly assaulting the arresting officers.

When Lewis was released on Jan. 4, his lifelong friend Dalila Reynoso was there to pick him up. He’d been told he did not qualify for continuity of care services; the Andrews Center would not be covering the price of his medication. Reynoso grew up with Lewis in Tyler and now works as an advocate with the Texas Jail Project in Smith County.

“Even in fifth grade, at TJ Austin Elementary, he was just sweet and patient and was really, really good in math,” she said.

That night, she drove him back to UT Tyler for another short inpatient stint in their mental health crisis unit. “He was actually excited, hopeful,” she said.

Today, Lewis is back in custody in Smith County Jail. After leaving UT Tyler, Lewis relapsed and flew into another schizophrenic episode. He was arrested after breaking into a Walmart after hours. He says has zero memory of the break-in, arrest or booking, and only became aware again once he was already back in jail.

“I told the sheriff, ‘Please, don’t judge my friend, this is not who he is,” said Reynoso. Recently, Lewis tested positive for COVID-19 and was placed in isolated quarantine.

Lewis emerged from quarantine last week. Jailers had started offering the vaccine while he was isolated, and he decided he wanted to take a dose.

“I was a little nervous of the shot but I just said fuck it, why not. Better late than never. They will not let me die in here.”