Cara Campbell

Audio By Carbonatix

Travis Strickland has been fighting the war on drugs for more than a decade. He’s a sergeant in the Lufkin Police Department’s special services division, which includes the street crime and narcotics units. The job used to involve taking apart methamphetamine labs that sprouted like prickly pears around rural Texas. Then Mexican drug cartels took over the meth trade and the labs moved south.

A couple of years ago, Strickland helped bring down two operatives linked to Joaquín “El Chapo” Guzmán’s Sinaloa cartel. Locals still recall the arrest; it’s not every day an army of federal, state and local law enforcement officers with a couple of helicopters descends on the parking lot of a Buffalo Wild Wings for a 26-pound meth bust.

“It doesn’t hurt my feelings that we don’t have any more meth labs because I hated taking those things apart,” Strickland says. “We didn’t know about the phosphorous gas and all the stuff associated with it. We do now. We suit up now. Back then, you just took a chance not to get blown up.”

Strickland isn’t a hardened, swaggering Clint Eastwood type of cop. Clean shaven with a conservative haircut, he could pass for a soccer coach as he takes a seat at a conference table one Tuesday morning in late November at the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas, a nonprofit prevention and treatment center that covers 13 counties. Several drug counselors, including Danna Bailey Watts, Tobin Wells and Brad Bell, join him to discuss what has been called a national emergency: the opioid epidemic.

The epidemic is hard to track, they say, because dealers usually can’t be found standing on street corners or in dark alleys peddling their drugs. Instead, they’re legitimate pain management doctors who, according to a recent federal lawsuit, have been duped by drug manufacturers to prescribe highly addictive narcotics to people suffering chronic pain.

Every day, 145 people in the U.S. overdose on painkillers, and deaths involving controlled prescription drugs have outpaced those of cocaine and heroin combined since 2002, according to the U.S. Department of Justice’s 2016 National Drug Threat Assessment. The epidemic has led several East Texas counties, including Bowie, Titus and Upshur, to file federal lawsuits to hold drug manufacturers such as Johnson & Johnson, Pfizer Inc. and Purdue Pharma Inc. responsible for the economic burden of the opioid addiction, estimated to total $78.5 billion nationally.

East Texas counties aren’t the only ones filing lawsuits. McLennan County, about 100 miles south of Dallas, recently filed a federal lawsuit against the country’s largest opioid manufacturers and wholesale distributors. The move came after county commissioners learned that their county’s rate of prescription opioid distribution was higher than state and national averages, according to an Oct. 31 report by the Waco Tribune.

Dallas County may soon join the tide. Dallas-based attorney Jeffery Simon says his law firm is one of three hired by the county “to vet the issue” and determine whether Dallas County will join nine East Texas counties Simon’s law firm represents in U.S. district court in East Texas. That would put Dallas in a growing trend of local governments around the nation filing lawsuits against drug manufacturers.

“The goal is to try to recoup the cost of the opioid epidemic,” Upshur County Judge Dean Fowler told the Longview News-Journal. “It costs our taxpayers to take care of people who are addicted to opioids, and the cost to the public is very high.”

Although many rural East Texas counties aren’t as densely populated as North Texas or considered high risk for opioid abuse like a metropolitan area, Simon says the financial consequences are sometimes significantly worse because the counties lack resources. That’s why rural Texas counties are stepping forward to file lawsuits.

“I think the thing we’re interested in is trying to recoup some of our indigent health care costs, if we can,” Rusk County Judge Joel Hale told the News-Journal.

At the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas, drug counselors say more than 90 percent of their clients are indigent, many referred by Child Protective Services and the courts. This year, they’ve seen an uptick in the number of people addicted to opioids seeking treatment – from one or two to about seven or eight per month – but still deal with quite a few meth addicts, which many say is the real epidemic still affecting Texas.

“But when someone comes in, they could be using several drugs,” Bailey Watts says. “We ask them what they are using at the time, and if they say meth, we list meth. So, to me, we don’t get a good count.”

Strickland says most of the people his department deals with, often on more than one occasion, have several addictions.

“Meth addicts, cocaine addicts, crack addicts, they also use pills,” he says. “When we hit houses on a meth warrant, we’ll also find Xanax, hydrocodone and OxyContin.”

“Pro-opioid doctors are one of the most important avenues that [drugmakers] use to spread their false and deceptive statements about the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use.” – lawsuit against drugmakers

Sales pitch

According to Upshur County’s lawsuit, the opioid epidemic can be traced to advertisements, or “pain vignettes,” as they became known, that depicted patients in physically demanding jobs and indicated that opioids offered long-term pain relief and functional improvement. They were part of a “deceptive marketing scheme” and one of several practices the county claims drug companies such as Purdue Pharma used to change doctors’ views toward opioids.

This change became evident from the increase in private insurance claims in opioid-related diagnoses in Texas from 2007-16, with San Antonio showing the largest increase at 141 percent, followed by Dallas at 41 percent, according to data from Fair Health, a nonprofit organization that tracks health care costs and health insurance information.

Doctors weren’t the only ones changing their views. The National Institute on Drug Addiction reported that teenagers nationwide viewed prescription opioids such as Vicodin and OxyContin as less dangerous than heroin. But according to a 2016 report by the Texas Department of Health Services and The Council on Alcohol & Drug Abuse, “a person addicted to prescription drugs needs a stronger dose each time to experience the same sensation of euphoria, and that stronger pull can lead to heroin, which is additionally alluring because it costs less [than opioids] and is easily accessible.”

Over the past two decades, the typical dosage of opioids prescribed per person increased dramatically in the U.S. and Canada, from 180 morphine milligram equivalents – the unit used to measure opioids – in 1999 to 640 MME in 2015. The drugs were more often prescribed in rural communities among white populations, according to the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. During the same time period, more than 183,000 deaths from prescription opioids were reported in the U.S., and millions of Americans are now addicted, says a June 2017 letter to the New England Journal of Medicine written by several researchers from the University of Toronto, the Institute for Clinical Evaluative Sciences, the Li Ka Shing Knowledge Institute and Sunnybrook Research Institute.

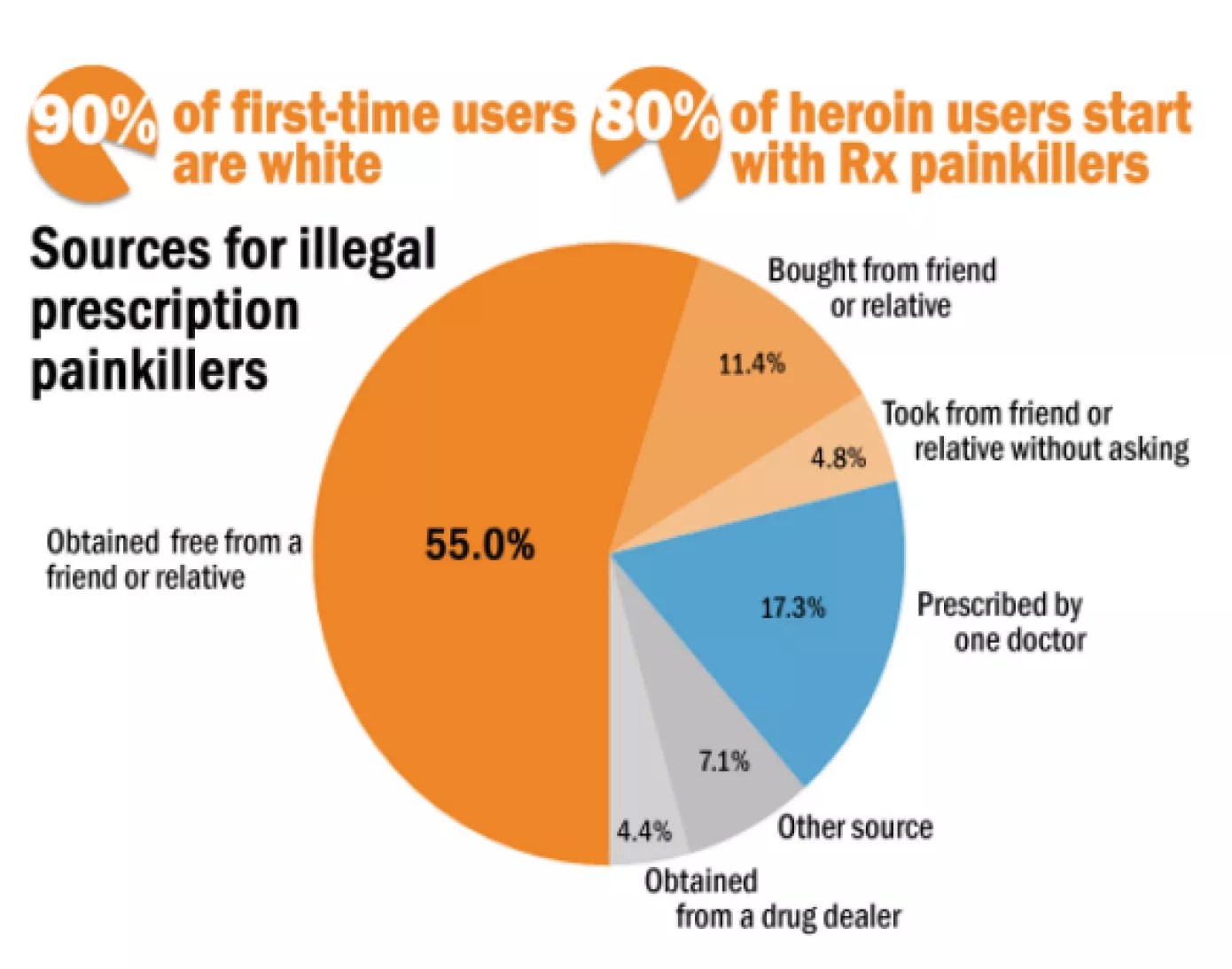

Sources for Illegal Prescription Painkillers, 2016

Source: Texas Health and Human Services Commission, 2016

“The crisis arose in part because physicians were told that the risk of addiction was low when opioids were prescribed for chronic pain,” they wrote.

Before the 1990s, doctors generally prescribed opioids for pain related to surgery recovery, cancer or end-of-life care. Using them for chronic pain, the lawsuit points out, was discouraged. Not enough evidence showed that opioids improved a person’s ability to overcome chronic pain. To change these views, certain drug companies used branded and unbranded advertisements that, according to the lawsuit, showed the purported benefits of opioids for chronic pain patients. The companies also employed sales representatives who marketed directly to doctors and medical staff, and they hired speakers who gave the false impression that they were “providing unbiased and medically accurate presentations when they were, in fact, presenting a script prepared” by drugmakers.

“You go to the doctor after back surgery and he gives you medicine, you trust that he is doing you right.” – Sgt. Travis Strickland, Lufkin police

“The marketing efforts of certain drug companies coalesced with what was called the pain management movement of the 1980s and 1990s, where the thesis was that the epidemic of untreated pain and the people who were suffering with pain was inhumane and the aversion that physicians had to prescribing narcotics to treat moderate pain should be modified,” Simon says. “They should be more liberally prescribing narcotics – opioid medication – as a standard treatment protocol.”

Certain drug companies also funded doctors known as “key opinion leaders,” or “KOLs,” whose professional reputations became dependent on promoting a pro-opioid message. They wrote articles and books supporting opioid therapy for chronic pain, participated in favorable research studies suggested by drugmakers, and served on committees that developed treatment guidelines and on boards of pro-opioid advocacy groups and professional societies.

“Pro-opioid doctors are one of the most important avenues that [drugmakers] use to spread their false and deceptive statements about the risks and benefits of long-term opioid use,” according to the lawsuit. “[Drugmakers] know that doctors rely heavily and less critically on their peers for guidance.”

Strickland characterizes it this way: “If you go on a dark street corner in the middle of the night and find some heroin and shoot it up, you know you’re doing the wrong thing. You go to the doctor after back surgery and he gives you medicine, you trust that he is doing you right – only to later realize that you’ve become an addict.”

It’s a realization that East Texan Cameron McAdoo made in the summer of 2016 when he sought treatment from Hiway 80 recovery center in Longview. McAdoo says a doctor prescribed opioids because he suffers from chronic pain caused by neurofibermitosis type 1. He soon found himself taking more than he was supposed to take in a day. He says the pain medication made him irritable and unpleasant to be around. He lost his house, his kids and his wife before he decided to seek treatment.

“Well, one thing I [had to] do in order to be honest with myself and doctors is tell them I am an addict and not to give me opiates,” he says. “Addiction is an everyday battle, and it’s not easy.”

OxyContin is one of the opioid medications adding to issues in Texas counties.

George Frey/Reuters/Newscom

A series of epidemics

At the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas, Strickland compares the opioid epidemic to the crack epidemic of the 1980s.

“One day everything was fine,” he says. “Then, overnight, everyone got murdered.” He says Lufkin had 17 murders in a year at the height of the crack epidemic in the late ’80s, and nearly 10 percent of its 32,000 residents were heavily involved in drugs and alcohol, according to a 1989 study by the Lufkin Police Department. It led to the formation of the narcotics unit.

The story was much the same when the meth epidemic cut a path like a twister across Texas in the late 1990s and early 2000s and the media began to publish reports about meth and its devastating effects.

“Everyone who is using it is going to die, but that is not really true,” Strickland says. “There is a lot of hype, but the thing about opioids is it’s always been here. Think about it. Everyone has taken a pill – a pain pill or muscle relaxer – out of grandma’s closest. It’s always been available. I just think now, for whatever reason, the media is really grabbing onto it and exposing the fact that it is a problem. I don’t think it’s become a problem. I think it’s always been a problem.”

Government officials have been trying to deal with the issue in part by holding drug manufacturers responsible for implementing prescription drug monitoring programs. In May 2007, Purdue Pharma, the manufacturer of OxyContin, and its three senior executives – top lawyer Howard Udell, former medical director Paul Goldenheim and President Michael Friedman – pleaded guilty to federal criminal charges that they had misled regulators, doctors and patients about the risk of addiction associated with OxyContin, which garnered $2.8 billion in revenue between 1995 and 2001, according to a New York Times report. They agreed to pay $600 million in criminal and civil penalties, one of the largest amounts ever paid by a drug manufacturer.

“Nearly six years and longer ago, some employees made, or told other employees to make, certain statements about OxyContin to some health care professionals that were inconsistent with the FDA,” according to a company statement. “We accept responsibility for those past misstatements and regret that they were made.”

Robert Josephson, a Purdue spokesman, says the company has taken several steps since 2007 to limit and monitor the marketing of its FDA-approved opioid pain medication. It has reformulated OxyContin with abuse-deterrence technology, supported national and community-based efforts to prevent opioid abuse, and imposed strict internal compliance programs to hold employees accountable.

“We are deeply troubled by the opioid crisis,” Josephson says. “We are dedicated to being part of the solution.”

To do so, the company has given grants to the National Sheriffs Association to provide officers with the overdose rescue drug Naloxene and committed $3 million to help form private-public partnerships with the Commonwealth of Virginia to enhance its prescription drug monitoring program. It recently announced a partnership with Project Lazarus and Safe Kids North Carolina to support statewide medicine disposal activities and conduct research to evaluate the effects of community-based prevention programs on opioid-related overdoses, abuse and diversion.

It also donated $1 million to the National Association of Boards of Pharmacy to establish PMP InterConnect, a system to help states share prescription data to help deter doctor-shopping across state lines. It’s used in more than 40 states, Josephson says.

In addition, Purdue has developed Researched Abuse, Diversion and Addiction-Related Surveillance, known as RADARS, a system to measure rates of abuse, misuse and diversion across the nation. It’s also partnering with the Connecticut Governor’s Prevention Partnership to run public service announcements about the risks of prescription opioids.

Josephson pointed to an editorial that appeared in the Wall Street Journal earlier this year that claimed state attorneys general are simply using lawsuits to pad their budgets.

“Governments are farming out the legal work to trial attorneys who front the bills in return for a share, typically 20 [percent] of the reward,” the Journal‘s editorial board wrote. “States used this contingency-fee model to squeeze $206 billion from the tobacco companies in the 1990s, and the ringleader of that effort, former Mississippi Attorney General Mike Moore, is assisting with the opioid raids.”

The Journal further claimed that although Ohio argues that prescription opioids are a gateway to street drugs and that deceptive marketing practices “resulted in the explosion in heroin use,” the vast majority of patients who take prescription painkillers don’t get hooked on heroin.

Purdue filed a response to Ohio’s lawsuit in September, saying it should be thrown out because the U.S. Food and Drug Administration approved OxyContin for use as a painkiller and its safety warnings.

“Unlike suits brought against tobacco makers … cases focusing on opioids are targeting a government-regulated product,” according to a Sept. 9 Bloomberg report. “That means judges must defer to the FDA’s finding that the painkillers are safe and effective, and that Purdue properly disclosed addiction risks on its warning label, according to the company’s filing.”

Josephson says that Purdue, Johnson & Johnson, and some lawyers for cities and counties want the more than 60 federal lawsuits filed in the U.S. so far to be combined. U.S. District Judge Sarah Vance of Louisiana warned that states and local governments faced serious legal hurdles that could derail their big-tobacco style bid for a multibillion-dollar payout, according to a Nov. 30 Bloomberg report.

“There are serious threshold issues when it comes to whether these governmental entities can sue for these damages,” Vance told attorneys.

“Meth addicts, cocaine addicts, crack addicts, they also use pills. When we hit houses on a meth warrant, we’ll also find Xanax, hydrocodone and OxyContin.” – Sgt. Travis Strickland, Lufkin police

Tightening the pipeline

The U.S. Drug Enforcement Administration placed hydrocodone combination products and other opioid drugs in a more restrictive category in October 2014, making them harder for doctors to prescribe and patients to obtain. Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas drug counselor Bailey Watts was working for a methadone clinic in McKinney when the DEA made the change.

“I think the schedule change made it a bigger problem,” she says. “We noticed a change in heroin users who were saying they were using it because they couldn’t get their pills anymore.”

Prosecutors around the country also began incarcerating more people, including parents, for opioid use. The Good Men Project, a media company, said in a June 29 report that this has placed a greater burden on the struggling foster care system. On any given day in the U.S., roughly 450,000 children are in foster care. Arizona, Florida, Georgia, Indiana and Minnesota accounted for 65 percent of the foster care increase, “much of it due to the opioid crisis,” according to the report.

“Just looking at the headlines in every state, one can see that data showing that our foster care systems are bursting at the seams with the increases of children coming into care,” Connie Going, the CEO of the Adoption Advocacy Center, is quoted as saying in the report.

Strickland points out that drug courts were established in 2001 to help people who commit crimes like theft to fuel their addiction. All Texas counties with populations exceeding 550,000 received federal and other funds to establish the drug courts, according to the Texas Department of Criminal Justice.

The Criminal Justice Policy Council released a study in 2002 that found individuals who complete the drug court programs have considerably lower recidivism rates over three years. “It’s pretty successful and more so than I thought it would be, especially if you are stealing to support your habit but not if you are a drug dealer,” Strickland says.

The DEA also implemented a national prescription drug takeback program in 2004 to provide a safe and convenient means of disposing of prescription drugs, as well as education about the potential for abuse. The program has collected more than 8.1 million pounds of drugs in 13 years. Last April, more than 450 tons of prescription drugs were collected at nearly 5,500 sites, including the Broadway Square Mall in Tyler, the parking lot of the Kilgore Police Department and the Church on the Rock in Daingerfield.

Texas legislators passed a law in 2009 to strengthen the prescription monitoring program, and the state pharmacy board has adopted, modified and recommended several changes to improve the program over the years. For example, a rule was adopted in September to require pharmacists to enter dispensing information in the program’s database within one business day of dispensing controlled substances. The board is also developing red-flag indicators, to begin in January, for potentially harmful prescribing patterns or patient activity.

The state now requires programs like the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas to start sending their clients with opioid addiction to medically assisted treatment centers such as methadone clinics to help them kick their habits. Most treatment centers, however, require clients to be detoxed first, and there are no longer any detox clinics in the Lufkin or Beaumont areas because of a lack of funding, Bailey Watts says.

Instead, counselors send clients to Austin, Dallas, Houston, Tyler or Waco. The waiting list for detox is usually two weeks, so county jails and prisons have become, by default, major detox centers, according to the 2017 regional needs assessment by the Region 5 Prevention Resource Center, which covers 15 East Texas counties.

“So for all of us who have been in the field a long time, it’s hard to get our head around it,” says Wells, who’s been working at the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas for more than a decade.

Strickland says pharmacists and doctors in Lufkin participate in what’s known as the triplicate program. It requires doctors to give each patient a hard copy of a prescription to be taken to a pharmacy instead of faxing it or calling it in. Some pharmacists require a patient to sign for the medication, but Strickland says they can’t force patients to sign it.

“You don’t have to sign for OxyContin, but you’ve got to sign for Sudafed,” he says.

For the past five years, doctors in this part of East Texas have also been requiring patients to sign pain management agreements promising they won’t get any type of pain medications from any other doctors in town.

“Not all doctors jumped on board at first,” Strickland says. “But over time, because of the liability, they are now usually the ones who call us first.”

Drug counselor Tobin Wells (left) talks with counselor intern Brad Bell and counselor Danna Bailey-Watts.

Cara Campbell

More addicts, more business

About 10 years ago in the Lufkin area, drug dealers selling opiates (drugs derived from the poppy plant) and opioids (manufactured drugs that mimic opiates) were mostly white, but that “old stereotype is no longer there,” Strickland says. He still sees more white people using opioids and opiates but claims more minorities are dealing them because the potential for making money has grown as obtaining prescriptions has become harder. OxyContin sells for $40 to $50 a pill, depending on its strength.

“Sometimes there is a lull where it is hard to get Oxy or something like that,” Strickland says. “It is probably the most fluctuating price that we have. Most dope, you can buy crack for this much, meth for this much, heroin for this much. It’s almost set in stone. But the pill market fluctuates on the amount that is in town and how much is readily available.”

When the lull happens, Strickland says, pharmacy burglaries increase.

Wells says some clients describe vans full of people that travel to Houston and drop each passenger off at different pain management clinics. He or she would answer a few questions to get a prescription for pain pills and Xanax, an anti-anxiety medication, or what Wells calls “the cocktail.” Then they would rotate until each person had visited all the clinics.

“That’s how they feed their habits,” Wells says.

In 2015, federal authorities claimed two Dallas men, Stanley James Jr. and John Ware, implemented a similar technique when they used drivers to pick up homeless people to pose as patients at various pain management clinics. Ware owned a series of clinics in North Texas that federal authorities claimed he operated as “pill mills.” James pleaded guilty in May 2016 to one count of conspiracy to distribute a controlled substance. Ware pleaded guilty in April.

At the Alcohol & Drug Council of Deep East Texas, counselors used to see only one heroin addict each month, but now they’re seeing four or five. “We’re relating it to that it is so much harder to get the pills, that the pill pusher is turning their clients into heroin addicts,” Wells says.

Most dope, you can buy crack for this much, meth for this much, heroin for this much. It’s almost set in stone. But the pill market fluctuates on the amount that is in town and how much is readily available.” – Sgt. Travis Strickland, Lufkin police

But Strickland says it’s the opposite locally. “They can’t get their heroin [which comes from the Dallas area], and they’re reverting to pills,” he says. “They’ll tell you right now that the pills aren’t as good as their street-level heroin. They would rather use heroin instead of crushing pills and shooting it.”

The first big opioid and opiate dealer to hit the Lufkin area came from Fort Worth a couple of years ago. He was visiting a friend and couldn’t find any pills or heroin to buy, so he moved his operations to East Texas. Strickland says it’s hard for law enforcement to bust these type of dealers. No one wants to snitch, he says, because it’s harder to get opioids and opiates. The dealer operated for about three months until one of his clients overdosed and a family member came forward to alert law enforcement.

“The [prescription form] opiate dealers is the fastest-growing form of narcotics trafficking we are seeing,” Strickland says. “There is a growing demand for these type of prescription drugs, and our local dealers are accommodating the demand by having the supply available.”

The Centers for Disease Control and Prevention reported that overdose deaths involving opioids have quadrupled since 1999, but Strickland says in a rural setting like East Texas, it’s harder to track overdose deaths because there’s no medical examiner. Justices of the peace sign death certificates when people die outside of hospitals.

“A lot of overdoses are maybe listed as a heart attack,” he says. “Autopsies cost money. If you are the JP, you have a budget and can only do so many a year. We want to save those autopsies for murders.”

Strickland and the drug counselors point out other ways they’re trying to combat the opioid epidemic in East Texas. They mention the difficulty of dealing with low-income families who receive government assistance and continue the addiction cycle because, in East Texas, they live in what Wells calls “plumes” – basically, little pockets of family living next to each other. That makes it harder for clients who want to get clean because they can’t escape their environment.

They also mention Leo the Drug Lion, who goes to the local schools to educate children about the dangers of addiction. They call him a rock star.

Strickland says his department is working five or six active investigations involving pill dealers and buying 200 to 300 pills at a time, but like many law enforcement officials, he’s frustrated with the system’s inability to differentiate between dealers and users and says authorities need to make the pills more unattractive to sell. He’d like to see stiffer penalties for opioid dealers, similar to what laws did with mandatory minimums when the crack epidemic swept across the country in the 1980s.

But even then, he’s not sure it will make a difference.

“We’ve lost the war on drugs,” he says. “We’re just trying to win a few battles here and there. As long as there is a demand for narcotics, there will always be drug dealers.”