So long, pressed pants and lost claim tickets. Hello strong boxes and shrink-wrapped bundles of cash.

Sinking into his leather seat on the private plane, Baccus told one of his friends on the flight, "This is first class. One of these days, I'd like to own one of these."

No reason to think it couldn't happen.

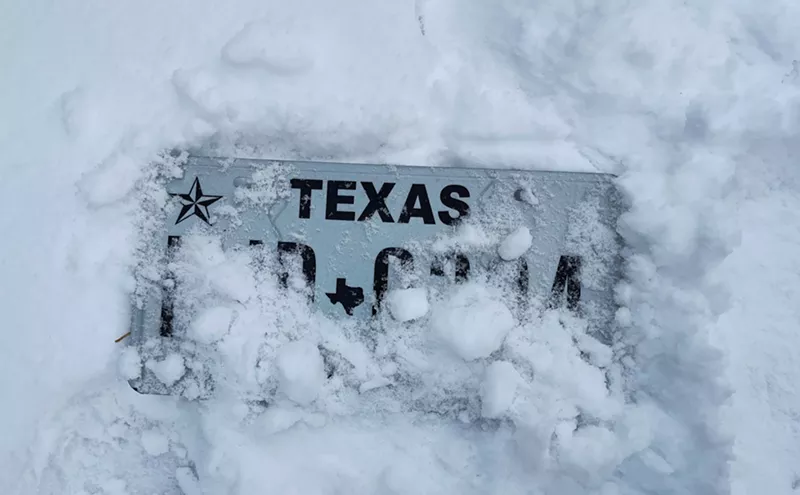

The flight originated at the Jet East Inc. hangar at the south end of Love Field and touched down on a little airstrip in Alpine, near the Davis Mountains in scenic West Texas. At 550 mph, it took about an hour.

Baccus and about a half-dozen other passengers returned east on the Lear that same day, landing in Monroe, Louisiana. From there, several associates continued on to Puerto Rico, where so-called warrants--which look like cashier's checks--with face values totaling $1.7 billion were to be deposited in a branch of a major Spanish bank in a suburb of San Juan.

It was a jaw-dropping sum. And this would be an unbelievable story if its central points were not spelled out in multi-count federal indictments handed up in Puerto Rico last December and in Dallas last May.

Beginning in April 1996, Baccus and four friends--three black men and a Latino--joined forces with the Republic of Texas, a separatist group that claims Texas is a sovereign nation and they are its legitimate government. Within months, these five Dallas-area men were moving in the Republic's top ranks, huddling with de facto leader Richard McLaren at his headquarters outside Fort Davis and chairing its well-attended public meetings. Mostly rural in membership and style, the Republic attracted a crowd you don't find very often in South Dallas: right-wing militiamen, self-styled "patriots," tax protectors, hate-group adherents, and the like.

"When I first heard of them, I thought they were a bunch of bubbas running around in the woods with shotguns," says Steve Crear, a 37-year-old former security guard and self-styled minister who became the Republic's vice president and only black officer. "Once I got into it, they treated me fine, even if it's 99.9 percent white," he says.

How these strange bedfellows slipped between the sheets, how the Republic of Texas went on to join forces with an oddball black separatist group in Louisiana called the Washitaw Empire, and how Crear and company began living large on private jets and plastic money--buying more than $150,000 worth of computers, clothes, guns, and such--are part of a wild, to-date-unexplored chapter in the history of the Republic of Texas.

It is a story whose general outlines are clear, although some details will become more sharply drawn next month, when Baccus, Crear, and company are expected to go to trial before U.S. District Judge A. Joe Fish.

Crear and Baccus, who have forsworn lawyers and are representing themselves, and codefendant Mark Hernandez, who has a court-appointed attorney, spoke at length several times with the Dallas Observer about their adventures in the Republic. They admit passing the bogus warrants, but say they believed the checks were legitimate and backed by various trusts--including an alleged lien that claimed to confiscate all of Texas' assets.

Their use of the warrants and participation in the smuggling trip to Puerto Rico are listed in a federal indictment charging Baccus, Crear, and Hernandez with conspiracy, mail fraud, and aiding and abetting. Baccus is charged with bank fraud as well. The three, along with alleged co-conspirators Joe Reece and Erwin Brown, were released on personal recognizance after their indictment was unsealed in early May.

McLaren, who with his wife, Evelyn, tops the 25-count federal charge, was at the center of the bogus checks scheme, authorities allege. He surrendered to Texas Rangers on May 3 and has remained in state custody in Marfa following his arrest on kidnapping charges at the conclusion of a six-day stand-off with state troopers. McLaren and six others--none of them Dallas men--had taken two neighbors hostage and held them for 12 hours as "prisoners of war."

The gist of the Dallas group's defense, which they mix with huge doses of the Republic's anti-government cant and charges of racism, is that they didn't know that what they were doing was a crime. "I thought this was all backed up," says Crear, referring to the phony warrants that all five are accused of passing to either banks or credit card companies. "They had documents that showed there was money behind them."

Says Baccus, chuckling at his own words, "I guess we were brainwashed." He insists his only goal was to open a bank to give interest-free loans to South Dallas' legions of poor--which he went about doing in a very public way.

A federal official close to the case says the government has evidence that the men "knew [the warrants] weren't good," which is why they were shipping them out of the country and attempting to pass them through a foreign bank. "They actually believed that the state of Texas was going to pay their credit cards?" the official asked incredulously.

Even after U.S. Secret Service agents arrested two co-conspirators who tried passing the warrants in Puerto Rico, Baccus attempted to deposit about $3 million worth of warrants in two Dallas banks, and Crear continued sending them off to American Express, where he'd run up a $112,800 bill.

Several other Republic of Texas leaders say they, too, were in a position to join in McLaren's warrants scheme. They not only declined, but say they warned Crear that the increasingly erratic McLaren was leading them on a path to jail.

"I think they were dupes," says Darrell Franks, an ostrich rancher from Shiner, a tiny town between Houston and San Antonio, who held the position of treasurer and split with McLaren last October, around the time the bogus warrants were beginning to fly.

Baccus, Crear, and company may have been taken in and misled by McLaren's confident ranting, but they went along willingly, he says. "As far as I could see, they were more interested in money than freedom," says Franks, who remains a Republic of Texas adherent but is not aligned with any of the three factions into which it has divided. "They were going for the bucks."

Steve Crear is a large man, as one might expect of a former starting linebacker for South Oak Cliff High School. In the team picture in the school's 1979 yearbook, he has a slim, athletic build. Eighteen years later, the former No. 65 is a hefty 265 pounds, and he makes easy work of a plate of smothered chicken at Lady Di's, a Grand Avenue soul food restaurant where he has come to talk over lunch.

He is, for the most part, a friendly, personable man, but he can get out of sorts when asked about the parts of his story he obviously is editing out.

Crear introduces himself as an evangelical minister, married with two kids. He was basically unemployed, making a few dollars selling tapes of his own sermons on a religious radio show--"One Minute Till Midnight" on KGGR-AM--when he first heard of the Republic of Texas in March 1996, he recalls. The group's co-founder, Richard McLaren, a 43-year-old former organic vintner who looks a lot like the Three Stooges' Larry Fine, was talking on a radio broadcast out of Waxahachie. Within a few days, Crear telephoned the group asking for more information, and he was invited to attend a meeting at the Grand Kempinski Hotel in far North Dallas in late April.

More than a thousand people showed up. Several who attended say it was jammed with the R.O.T.'s typical adherents: militia members, eccentric-sounding "common law" specialists, the economic walking wounded. But Crear recalls a far spiffier crowd. "I saw a well-coordinated platform for intellectual people, college-educated people...people with a love for freedom," he says.

Crear addressed the group for a few minutes to talk about what a new Texas regime might mean to blacks. "I told them black people know a thing or two about losing their freedom," he recalls.

Afterward, he introduced himself to Franks, treasurer of the so-called provisional government's leadership council, and Archie Lowe, a computer technician from Rice who was to become the group's president.

Crear started sending away for videotapes of movement speakers--one, for instance, on how the U.S. money supply is part of a conspiracy to keep people in debt--and attending more R.O.T. get-togethers. Almost immediately, he says, talk with Franks began focusing on opening a South Dallas bank underwritten by the Republic.

For help with that, Crear turned to Baccus, whom he'd met three years earlier.

Baccus, a bantam rooster of a man, balding and gravel-voiced, is a familiar figure in South Dallas. As chairman of the board of the Pylon Salesmanship Club, a black business organization, he is a popular source of quotes for parts of the Dallas media--as often as not blasts at the white business establishment.

Dust-covered sports trophies, family photos, and antique dry cleaning equipment drift up in Baccus' shop, which for the past 37 years has been in the same stone building. It is run these days by three of Baccus' 14 kids; another son runs a second location in Lancaster.

Among the photos on the walls are snapshots of the three women who have divorced Baccus over the years, the latest under circumstances that only added to his reputation as a ladies' man, or so the gossip goes. He also is music director at the Cedar Crest Church of Christ, which he attends regularly. Once he began attending Republic of Texas functions, Baccus often would be called on to deliver the opening invocation.

Within two months after Crear first heard McLaren's high-pitched voice on his radio, a delegation of R.O.T. leaders traveled to a church in South Dallas. There, McLaren talked with Baccus and Crear about the bank, which would offer no-interest loans to poor people and make its money through small fees, and in late June, Baccus--along with Crear and three friends--drove to Shiner to sign an application for a Republic of Texas bank charter. A photo taken to mark the event shows a smiling Baccus handing the balding Franks a $2,000 check sealing the deal.

Within a week, a signed contract shows, Baccus put $5,000 down on a contract to pay $700,000 for a bank building at 3300 Commerce Street, at the edge of Deep Ellum. It once housed a for-real Republic Bank.

In late July 1996, Baccus invited about 200 people to a press conference at the Baby Back Shaq, a little South Dallas ribs place, to announce the coming of the South Dallas Republic of Texas Bank.

"Most of the time, we [blacks] are the last ones to get in on something good," Baccus told the crowd. "Now we're the first ones to get in."

Catherine Ghiglieri, the Texas banking commissioner, told reporters that day that the Republic did not have the authority to issue bank charters. But Baccus, sounding well versed in the Republic's revolutionary spiel, told The Dallas Weekly, a black newspaper, that the commissioner's statement was just "a scare tactic."

"Anytime that you're out trying to help somebody and it's going to hurt the people that's been crooking and taking from you all these years, they're going to be hollering," Baccus said, echoing the anti-banker language that saturates the Republic's rhetoric.

Behind the scenes, Franks had signed up dozens of individuals for bank charters, but he told Baccus that the South Dallas bank would be the first to open--as a test case. Baccus recalls Franks telling him the new nation would use his bank to store its reserves of silver and gold.

The way South Dallas residents reacted to Baccus' announcement depended on what they thought of him already, and how much they trusted the idea of a crew of middle-aged white guys from the boondocks riding into South Dallas to loan them money, free of charge.

Joe Howard, editor of The Black Economic Times, says he laughed when he heard Baccus had hooked up with "these bandit white boys that store arms and talk about how they're put upon."

In Howard's opinion, the strange alliance was particularly ironic because Baccus had always been quick to blame whites for black Dallas' economic ills. But people did believe Baccus, he says. "You stay on the same corner for long enough, and people think you know what you're doing."

Says Dean Watson, a South Dallas bookkeeper who plays golf with Baccus and has known him for almost 20 years: "He has a good reputation. He works with a lot of different civic organizations. I thought that bank was something real going on."

But there are people with longer memories who remember that Baccus almost went to prison for another scheme more than 20 years ago. According to federal court records, Baccus and another man, a Baptist pastor, were tried in 1975 and found guilty of setting up a sham consortium to train hard-core unemployed to work in the dry cleaning business.

Baccus and the minister contracted with the U.S. Department of Labor's Manpower Administration to be paid $1.2 million to train 450 people. The dollars flowed, but the training did not, testimony showed. At Baccus' trial, a subcontractor testified that he showed up at the minister's church, where the training sessions were to be held, and all he found was an empty, unfurnished room.

Later that day, the subcontractor testified, he met with Baccus, the minister, and several other men who knew them. Someone in the room--he couldn't say who--told him he had better get lost if he wanted to "continue to be in good shape." He recalled for the jury someone telling him, "We are going to get you, whitey."

Baccus went on to appeal the conviction and the five-year prison sentence U.S. District Judge Sarah Hughes imposed on him. He won a reversal on a purely technical matter. Baccus' indictment, the appeals panel ruled, was handed up several months beyond the five-year statute of limitations, based on when he signed the government contract. Nothing in the court record indicates what ever happened to the contract money.

Asked now about the case, Baccus says: "I was no-billed on that. I got a good Jewish boy as a lawyer, and I was no-billed."

Says a friend and occasional golf buddy who plays with Baccus on his frequent outings to South Dallas' public courses and private clubs, "Jasper's life is an open book...Sometimes he's been on the other side of right."

While Baccus was moving ahead on the banking front, Crear was getting ahead in his own way. He was politicking his way into the Republic's vice presidency.

In the June issue of the organization's magazine--which featured on its cover a cartoon of a man, smoking shotgun in hand, hanging up the dead carcasses of wolves labeled FBI, IRS, and ATF--Crear wrote of his admiration for McLaren, Lowe, Franks, and several others: "I realized these people were not crazy but some of the greatest men and women who are the true[est] seekers of freedom that I have ever met in my life."

Sarah Lowe, the Republic's first lady, says she and her husband pushed to integrate the organization and bring in blacks, Hispanics, and Jews. "My husband thought Steve was a godly man bent on liberation of his people," she says, adding that she and her husband considered themselves Crear's most ardent supporters until a split earlier this year.

After Crear was sworn in at an August 1996 ceremony at the Big Texan, a steakhouse tourist trap in Amarillo, "there was a lot of tension about it," Sarah Lowe recalls. "We were surprised by how much bigotry there was."

Baccus recalls, "They started calling meetings and didn't let [Crear] know about them."

For most of last summer and into the fall, Crear and Baccus were regular fixtures at Republic meetings, which were run under parliamentary rules, as if they were running a government.

The two men drove or flew to San Angelo, Amarillo, Tyler, Houston, Waco, Beaumont, and Midland. And they enlisted three close friends into the cause.

One was 28-year-old Mark Hernandez, who was working at the time as an equipment technician at Children's Medical Center. Hernandez says he met Crear 10 years ago at the hospital, where Crear worked as a security guard between about 1986 and 1995.

"Steve said he could have paid staff," says Hernandez. "I was supposed to make $120,000 a year as advisor to the vice president." He says he was planning to continue his studies at Brookhaven Junior College, but he thought a two-year stint with the Republic would leave him enough to pay the bills.

Top officers like Crear were supposed to be pulling down either "50,000 ounces of silver per year" or $250,000, depending on who is talking.

Crear also brought in Edwin Brown as an aide. He also had met Crear while working at Children's.

Baccus introduced another man to the mix, Joe Reece, 57, who Baccus says was supposed to help him landscape his bank building--a three-story 1970s-era concrete, glass, and brown brick edifice surrounded mostly by parking areas and drive-through lanes. Reece, state court records in Tarrant County show, was arrested by a multi-jurisdiction drug task force in Fort Worth and indicted for delivery of more than 14 ounces of cocaine in 1990. Under a plea bargain in 1991, he was convicted of possessing more than 14 ounces and sentenced to 10 years in Texas prison.

He served less than a year. (Reece could not be reached for comment.)

By last fall, nearly everyone in the Republic was talking about money in one way or another--or so it seems from the reams of faxes the group issued, notices in its magazine, and a videotape of a leadership meeting in Temple in early October.

It started at the top, with McLaren, who in his lean-to/trailer in the arid mountains had no visible means of support. "I must have given him $35,000 over a period of a few months there," says Franks. "He always needed money."

Franks, too, was talking money, although in more theoretical terms. Franks put out an announcement that "treasury bonds or certificates will be issued" against the so-called "eminent domain lien." This was one of the Republic's preposterous phony documents that Crear and company say they thought were good simply because the Texas Secretary of State's office file-stamped it and put it on record.

The lien lists as debtors "the United States Inc., d.b.a. State of Texas" under "their CEO William Jefferson Clinton operating through its lower agent George W. Bush." Taking up five pages of redneck gobbledygook, the document makes claim to the state's treasury and all its assets: buildings, air space, natural resources, roads, bonds--everything "on, over or under the soil of Texas."

(The validity of liens--which are used to collect legitimate debts--is determined in the courts, not by recording offices that put them in the public record, says Lorna Wassdorf, deputy assistant secretary of state. The Texas Legislature passed a law this year making it a crime to file bogus liens such as the Republic's "eminent domain" claim.)

Franks also told Baccus, in a memo attached to his bank application, that the South Dallas bank would be capitalized at $100 million, and that he was working to "access clean lawful funds and money" from something called the Central Dominion Trust.

Sarah Lowe and others in the movement now say that the Central Dominion Trust was a mythical creature--but Franks was constantly telling people to be patient, that the funds would come.

By October, McLaren was out of patience. He had asked council members to organize their budgets, and they presented their lists of wants and needs at the October meeting in Temple. Secretary of Defense Ralph Turner, a barrel-chested man from Pottsboro, announced only half-kiddingly that "I've always wanted an F-16." The former member of the Texas Constitutional Militia said $35 million would be enough to get his "defense forces" through the end of the year.

McLaren, who held the title of ambassador, said a staff of 200 would be enough for him to begin implementing his plan to put "satellite uplinks" in the back rooms of an unnamed "worldwide chain of restaurants," through which people around the world could learn about "the nation called Texas."

Following the main budget session--which ended in the Republic of Texas equivalent of a continuing budget resolution to hash things out later--the group repaired to a smaller meeting room at Temple's Holiday Inn.

There, McLaren gave the run of the meeting to a 41-year-old from St. Mary's, Kansas, named Ronald Griesacker, aka "Arthur." Darrell Franks brought Arthur into the organization as a "legal and banking consultant," and he came with a heavyweight reputation in militia-freemen circles. Sarah Lowe says she came to view him more as "just a mean little man."

Dressed in a wrinkled work shirt and jeans, his face covered in a close-cropped beard, Griesacker spewed rivers of arcane banking language and legal malarkey for the standing-room-only crowd. Talking with a kind of wide-eyed glare, he described himself as an expert in "admiralty law, common law, ecclesiastical law, and the law of necessity." A videotape of the meeting shows Baccus, dressed in a dark suit and Oleg Cassini tie, listening intently to Griesacker for a while, then becoming impatient and bored.

It is difficult to tell whether anyone but McLaren and Griesacker knew what they were talking about with all the banking jargon and legal mumbo-jumbo being tossed around. But both men announced they were looking to construct a way to use "warrants" to tap into an unnamed supply of money.

"Let's get a clearinghouse into place, and let's roll it," the lanky McLaren said excitedly. Predicting exactly what would happen over the next month, McLaren said the warrants "will come in from various directions...People will be depositing them in their accounts...and we have the ability to bring some in offshore."

After the council voted to establish the clearinghouse--and bickered for hours over the language of their resolution, including where to place a couple of commas--Crear called Baccus to the head table to offer a prayer.

"What we have accomplished today is worthwhile," Baccus told the group as he bowed his head and began. "We're so thankful, our heavenly Father, for this meeting tonight."

Around this same time, Crear, Baccus, and company were helping to write perhaps the most bizarre chapter of all of their revolutionary tale: their alliance with Verdiacee Tiari Washitaw-Turner Goston El-Bey, self-anointed Empress of the Washitaw Empire.

Just think of the Washitaw Empire as the Republic of Texas' like-minded, next-door neighbor who happens to be black.

It is led by the history-obsessed, dreadlock-wearing Empress, a lady in her late 60s who reigns from her second-floor apartment in a working-class section of Monroe, Louisiana, a city of 55,000. Like McLaren, the Empress has a thing for revisionist history and the issuance of official decrees.

"Return of the Ancient Ones," her 460-page unpublished jumble of personal recollections, irrelevant historical documents, antique maps, and rambling observations sets out the Washitaw Empire's claim to being North America's original inhabitants: "Across the Atlantic they came to the Gulf of Mexico, up the old Mississippi to the Washita, the blacks of African descent came. A highly intelligent race of ship builders, masonry [sic], a tribe of Israel, black and bushy-headed. They were the Washitaws."

The text gives no evidence of this migration, which is supposed to have occurred before 2000 B.C., except to say it is so. Similarly, the Empress claims to be recognized by the United Nations.

The ancient people, she writes, built villages of octagonal dirt mounds, and lived to be 120 years old. "They were indigenous, not Indians...the ancient black nation was here in the Washitaw de Dugdahmoundyah." The word "Dugdahmoundyah" means that they were people who dug mounds, the Empress explains in a brief interview.

"Before Columbus," she writes, "the Black Moors traded with the ancient ones via ships of Shitta. Ware-shittinwood or water-shitta=Was=shita--now Washitaw...The Europeana then came to the new world to rule over the colonies for themselves and started a slave trade to hide what they were doing to the black Moors or Muurs already here."

The 1803 Louisiana Purchase, in which France sold the United States lands between the Mississippi and the Rocky Mountains, was part of that plan of oppression, the Empress believes. In fact, she insists that the Washitaw Empire still owns the entire area.

Much like the Republic of Texas' lien that purports to take back Texas' assets, the Empress has demanded that the United States pay her empire "eighty quadrillion USD" for "relief of the debt owed" for the Louisiana Purchase lands.

Last month, the Empress printed up a demand "subpoena" on the nation's letterhead, which is topped with the group's name in the same Nazi-style typeface used in many of its documents and its newspaper, the Washitaw Post.

The letter is stamped with a gold seal: the word "LOVE" surrounded by the group's name.

Contacted on the Empire's toll-free number (1-888-WASHITAW), the Empress declines to comment on Crear, Baccus, and their friends, although she concedes that she knows they are under federal indictment.

Crear, Baccus, Hernandez, and others say they made multiple trips to Monroe to meet the Washitaw leadership, to whom they were first introduced by Reece.

They say they were opening up "diplomatic relations" with the Empire, but they joined up as well and now also claim to be "of indigenous aboriginal heritage." Crear, pulling a photo-ID Washitaw "international motor certification" from his wallet, says the Empress "brought out a chart showing that I'm related to her on my mother's side."

Hernandez says he joined the Washitaw too, setting up a dual allegiance to the Empire and the Republic of Texas. Baccus says he was planning on joining as well, but "I just haven't sent in my application."

Using a private prop-driven plane provided by Treasurer Darrell Franks, McLaren and Franks, along with Baccus, Crear, and friends, flew from Meacham Airport in Fort Worth to Monroe to meet the Washitaw leadership last fall. "They talked about bringing some currency through their [the Washitaw's] banking institutions," says Crear, declining to elaborate further.

Crear says that he and Baccus and other Republic officials flew to Monroe several more times. By late October or early November, McLaren had printed a supply of bogus warrants, and all the theoretical talk about a new Texas government and a new banking system was about to become what federal authorities claim was a conspiracy to commit bank fraud and other major financial crimes.

As a matter of philosophy, Republic of Texas adherents and freemen groups like them believe that U.S. money--federal reserve notes backed by the full faith and credit of the government--is worthless. "They figure the government creates money out of air, so nobody's money has value," says Joel Dyer, editor of the Boulder Weekly and author of the recently published book Harvest of Rage.

Dyer's book, which explores America's late-20th-century radical right, puts forth a thesis that farm foreclosures and factory closings have turned decent, hard-working Americans into conspiracy theorists, many of whom believe the government is in league with the devil. Because banks, lawyers, and government officials are the ones believed to be inflicting this economic pain, they are mistrusted and hated, Dyer says.

While researching his book, Dyer happened to be in McLaren's Fort Davis compound early last November, when Griesacker and McLaren were hard at work at their warrants scheme. "They spent a lot of time and energy figuring out how it would work," he says.

By that time, Dyer says, McLaren and Griesacker had split with Franks, who had another idea about how Republic monetary policy was going to work.

Jeff Katz, the Republic's secretary of science and technologies, printed up a batch of 1,375 warrants for Franks in mid-October, according to an invoice from Unltd Sply, Katz's Carrollton printing company. He says his batch--for which Franks paid him $1,100--was never circulated, and at least three other sources agree.

The Franks-McLaren split turned out to be a policy rift over which banking fiction, which paper myth, they were going to follow. Franks says he opposed writing warrants that drew on the "eminent domain" lien. In his view, "the state is broke." He wanted the new government's system to be backed by gold, so he put his warrants "in a safe place" and permanently split with McLaren in late October. A flurry of faxes in which the two men condemn each other--and disavow each other's warrants--backs up this version of events.

During that fall, Crear says, he started using his own Spearhead Ministries' corporate American Express gold card for tens of thousands of dollars of purchases, believing he was going to be reimbursed by the Republic. "I know it seems wild, but they said they were going to reimburse us for my expenses and salary," he says of the two or three people above him in the movement.

He claims that about 90 percent of goods he bought were for the Republic of Texas--computers, radios, guns, tents, camping gear--although he declines to show receipts. "Maybe 10 percent were things I bought for myself and my family," Crear says.

In a note dated October 15 sent from Franks' fax number and signed by the treasurer, Franks asked Crear to "submit a list of priority expenses that need to be paid immediately...If this list is not received by [October 18] your office will have to wait until the next issuance of warrants."

That was about a week before Franks says he pulled out of the group.

Hernandez says he, too, started running up his American Express gold card, chartering private jets for flights from Dallas to West Texas and Monroe. The idea, says Hernandez, was that the Republic and Washitaw Empire were going to work together to turn the warrants into U.S. dollars, what was called "monetizing the lien." "I'm just a hospital tech," says Hernandez. "You think I thought this stuff up?"

A man named Donald Calhoun, who lists in court papers a Los Angeles address and an office on Wilshire Boulevard, emerged as the Washitaw's point man in the scheme. He had the title of the Empire's minister of finance, according to Crear, Hernandez, and Franks.

On one trip last fall, Hernandez and Baccus say they accompanied Calhoun by commercial flight to Los Angeles, where Calhoun told them he ran a financial planning office. "It looked like a real office to me--there were lots of people in there," says Baccus.

He says Calhoun carried a batch of warrants into a branch of the Bank of America, but that he is not certain what transpired. "I know he didn't come out with any money."

Meanwhile, Crear started sending warrants that were made out and signed by McLaren to pay his hefty bills from American Express. The federal indictment lists the face value of the warrants Crear sent: "$12,000 on Nov. 4, $30,000 on Nov. 23, $38,000 on Dec. 20; $150,000 on January 3." The warrants, which look like checks, are marked "payable on sight" and backed by the "full faith and credit of the people of Texas."

Crear says his notices would come back marked paid, then his account would be debited again in later months--apparently when the warrants failed to clear. All along, Crear and Hernandez say, McLaren insisted that the only problem with the warrants was that the credit card companies and other institutions were not processing them correctly. In all, a spokesman for American Express says, the company lost $150,000 in the Republic warrants scheme.

Hernandez, who is charged with sending a $42,000 bogus warrant to American Express, says he also mailed them to nine other companies--including CompUSA, Best Buy, and Montgomery Ward--for consumer debts, including a bill for a $3,800 Toshiba laptop computer. At least one bank credited his account and, 10 months later, continues to say the payment was good. In an August 1, 1997, letter, Beneficial National Bank, which held his CompUSA account, wrote him that his payment of $1,000 was received in November, "making balance on account $0.00."

To this day, Hernandez says he doesn't know whether the warrants were good or not, but he stopped using them in early November, just after the Puerto Rico adventure.

"It was activity between two governments." That's how Crear describes the trip to the Caribbean, which a federal indictment alleges was made by Mark Hernandez's father, Jose Hernandez of McAllen; Donald Calhoun, the Washitaw's money man; and two people the feds allege Calhoun hired in Florida to find them a bank.

Mark Hernandez says he rented a jet in Dallas, traveled to West Texas with Crear, Baccus, and company, and then went on to Monroe. Baccus, asked about his presence on the flight, says, "I didn't know anything about the warrants." He acknowledged in another interview that the warrants were on the plane.

Parts of the trip--such as the boarding of the jet--were videotaped by Hernandez, says Crear, adding that he is certain federal prosecutors have a copy of the tape.

Baccus and Crear claim the warrants were provided by another Republic of Texas member, Richard Kieninger, whom they knew as the trustee of Republic of Texas Trust. Kieninger carried the warrants and handed them to the Empress in Monroe, Crear and Baccus say.

Kieninger, who on Republic budget documents from last October is listed as an underling of Archie Lowe, concedes that that was his role. "But I haven't done anything wrong...The warrants were legitimate. They were going to fund the Republic," he says.

He adds that Crear and Baccus were the activists in the organization. "Everybody was speculating and philosophizing," says Kieninger, a resident of Quinlan in East Texas. "They were the only ones who went out and tried to get something done."

Mark Hernandez says he was supposed to go along on the last leg of the Puerto Rico trip to act as a translator, but he was due back at his job setting out medical instruments on trays at Children's. So his father, who identified himself later to authorities as a Republic member, agreed to take his place.

A sworn affidavit by Javier Saldana, special agent for the U.S. Secret Service, provides an outline of what happened next.

On November 12, Carmen Vega, described in court papers as head of Orlando, Florida-based "Global Consulting," and a man who later described himself as a bodyguard visited a number of banks in the San Juan area. Vega told the agent later that she had been hired by Calhoun to establish "banking relationships in several states and countries with the purpose of opening bank accounts for and on behalf of the Republic of Texas." The deal promised Vega $1.5 million for the first account successfully opened, and 10 percent of all the warrants deposited, a copy of her contract with Calhoun states.

On November 13, Jose Hernandez and Calhoun opened a commercial checking account under the name KDMMF Associates at the Banco Bilbao Vizcaya, which Vega had visited the day before, and presented a Republic of Texas warrant for $5 million. The manager there thought the check looked suspicious and alerted the Secret Service, which has jurisdiction over counterfeiting and related crimes.

That same day, the service's financial crimes division and the Comptroller of the Currency in Washington, D.C., verified that the warrant was fraudulent. The Secret Service immediately brought Hernandez and Calhoun in for questioning and, after obtaining a search warrant to open Calhoun's briefcase, found $1.5 billion worth of Republic of Texas warrants inside.

Vega, who was not charged, surrendered $192 million more.

Most were made out to "Cash" for amounts such as $100 million or $25 million.

Calhoun told the agents that he would do whatever is necessary to "get money away from the government," and that all it would take was a phone call to get more checks.

Apparently he was not boasting. Less than six days later, federal agents arrested Calhoun again at a Ramada Inn in Monroe. He had been driving around in a Lexus 400SC, attempting to buy expensive things with more bogus Republic of Texas checks, government investigative documents allege. The shopping spree included five new Chevrolet Suburbans and $2 million worth of property located in nearby Winnsboro, Louisiana. He told the agents that he was purchasing the property for Verdiacee El-Bey, the Washitaw Empress.

Even though he had just been arrested days earlier in San Juan with the warrants, Calhoun told the agents a familiar tale: He said he was a victim in the scheme, ignorant of the fact that the warrants were worthless fakes.

The next month, a federal grand jury in San Juan indicted Calhoun and the elder Hernandez for conspiracy and bank fraud--to which Hernandez has since pleaded guilty under an agreement in which prosecutors said they would not oppose a request for probation.

Calhoun's case is pending, federal officials in San Juan say. A week before the Puerto Rico indictment was delivered, Baccus was doing a little banking of his own in Dallas.

On December 3, he deposited a $525,000 warrant in NationsBank, and the next day a $2.5 million warrant in Bank One on East Mockingbird Lane. Kevin Robbins, head of a South Dallas small business consulting firm called the PIC Association, even wrote a Bank One officer a letter of introduction. "Mr Baccus is entering a new business venture and is very cautious of this transaction," Robbins wrote. "Please take normal precaution to protect all concerned. For example, please restrict access to deposits until all funds have been collected."

Robbins, who says he wishes Baccus would refrain from circulating his letter, says he has only good things to say about Baccus, whom he calls a close friend. As for the warrants, "We didn't see some of the things that were there," Robbins says, declining to be more specific.

McLaren then wrote the banks as a representative of Republic of Texas Trust--which was supposed to make good on the warrants--and told them they had received the funds, the indictment alleges, which was yet another act of fraud.

When the banks told Baccus the funds were uncollectable, he says, McLaren insisted the banks simply weren't processing the paperwork properly.

Crear says that when his American Express bills didn't clear, McLaren sent him a letter that he, in turn, forwarded to American Express. In it, the government alleges, the Republic threatened to "file the enclosed application for a letter of reprisal against your company, its assets and the personal assets of everyone connected to the fraud in this action."

By last February, the Republic of Texas had split into at least three factions--with Crear sticking it out with McLaren and taking the title of acting president. "Everybody heard about McLaren loading warrants into a plane and sending them off to Puerto Rico with a bunch of black guys," Jesse Enloe, a leader of one of the splinter factions, recalled last spring. "That got people real mad."

By that time, Crear and Baccus say they had let matters rest at the banks and American Express. The company had sent Crear a statement in April showing his account had been credited with the warrants--a total of $112,816. The next month, his wife, Johnetta, requested a refund for a $28 overpayment, and the company sent it along on May 29, documents show. In late April, Franks returned Baccus his $2,000 check for the bank charter.

That was just two weeks before Crear, Baccus, and their three associates were arrested at their homes by swarms of federal agents, including IRS criminal investigators and postal inspectors. When the indictment was unsealed, U.S. Attorney Paul Coggins described the warrants scheme as an attempt to "rip off our residents and then ride into the sunset by wrapping themselves in militia double-speak."

Mark Hernandez, who had worked for Children's Hospital for 10 years, was fired the day of his arrest--receiving a dismissal letter saying he put the hospital in a bad light by associating with alleged criminals. Crear, who normally has plenty to say, remembers he was speechless when Judge Fish told him at the arraignment he could be sentenced to 185 years. "I don't know how I got into it that deep."

As alleged co-conspirators of the headline-grabbing McLaren, Baccus and Crear face a grave situation in the courts.

Still, instead of hiring lawyers to push their "I-didn't-know-these-things-were-fake" defense, they have waged a philosophical battle laced with right-wing rhetoric, allegations of racism, and pronouncements about being sovereign citizens of the Washitaw Empire beyond the reach of these "illegal" courts.

"So that's what all that says," says one government lawyer, cracking wise about the impenetrable briefs Crear, Baccus, Brown, and Reece have loaded into the court file.

Crear, who carries a Black's Law Dictionary to interviews and quotes from it liberally, says he is getting help from some unnamed "legal counselors"--and it shows. His writings have the tell-tale ring of far-right do-it-ourself law: allegations that federal courts practice some sort of military law, assertions that the gold-fringed flag in the court has a sinister meaning, quibbling over whether one's name can be capitalized, blasts at lawyers as evil agents.

Crear has added one new twist. In a three-page "demand to transfer" filed in the court in August, he asserts that he is of "indigenous aboriginal heritage" and insists his case be heard by Verdiacee El-Bey, the Washitaw Empress in Monroe.

Baccus, meanwhile, wrote letters to Bank One and NationsBank last month telling them he intends to sue because they have neither returned the warrants nor deposited funds in his account.

In unguarded moments, Baccus and Crear concede they were finished with the Republic of Texas some time ago. "I was through with it. I felt I'd been used," says Crear. "Nobody returns my calls now...Everybody's trying to hide, because lots of people were in on the warrants."

And from other files in the courthouse, it appears these men aren't quite as aggravated with the legal system as their briefs indicate--that is, as long as they are the ones looking to gain. In the past four years, Crear has filed three different civil suits seeking damages against various companies and people.

He unsuccessfully sued a DART contractor in 1993; a towing company in 1994; and this past April, a mere week before his arrest, he filed a case against a Dallas streets contractor. Crear alleges in that latest trip to the courthouse that he stepped on a manhole cover near Children's Medical Center in 1995. It "slipped off and caused him to fall into the manhole," causing him "severe bodily injuries" and "great physical and mental pain," his suit for an unspecified amount of compensation alleges.

Baccus too has litigation pending. In September 1996 he sued a Dallas couple, alleging they caused an auto accident that left him with injuries to his back, neck, head, and shoulder and caused "nervousness, tiredness, dizziness, and nausea." Opposing counsel labeled the suit an attempt to "extort a settlement."

"Oh," says Crear when asked about his pending civil claim. "I was gonna have that transferred to the Washitaw too. I haven't had time...I'm a little tied up now with this thing in federal court.