No one disputed that, but some people are still wondering if the jury that acquitted him might have said something different. Those discussions come down to the government’s basic theory of the case.

The best thing the federal government had going for it in previous landmark public corruption trial victories in Dallas was the one it did not have in the just concluded bribery and tax evasion trial of the 67-year-old Price – a big enough flip.

Some small-fry collaborators gave evidence. But no key co-conspirator turned against Price, Dallas County’s longest-serving and highest-profile African-American elected official. Not the rich white people who were the source of the “stream of benefits” the government described as bribes that bought his vote. Not the two black co-defendants who were the people most intimately involved in the commissioner’s political and financial life. In more than a decade of investigation and legal chess moves, the FBI, IRS and U.S. Justice Department failed to get a single one of those to budge.

That meant during the seven-week trial concluded last week, not one person at either end of the stream – people handing out the money, people raking it in – would sit in front of the jury, confess to the whole thing and tell how it worked.

The jury ground through eight days of deliberations and finally rendered verdicts Friday that gave Price a ragged but nevertheless momentous victory. He was found not guilty on seven counts of bribery and fraud. The jury told the judge it was hopelessly deadlocked on four remaining tax evasion charges.

Prosecutors told the jury that the alleged bribery, fraud and tax evasion scheme only touched the tight circle of Price, his administrative assistant, Dapheny Fain, and his political consultant, Kathy Nealy.

The government’s version was that Price leaned on would-be contractors and other companies doing business with the county to hire Nealy as their political consultant and pay her fat fees. The companies that paid her, the government said, did so without any inkling or suspicion that she might be passing some of that money on to Price.

Nealy gave Price the money as bribes, the government said, so that he would do things – vote or pressure other commissioners to vote certain ways – that would make her look good to her clients. Nealy was the only bribe-giver and Price the only taker. Fain helped hide the money, according to the government.

Therefore no companies came to court confessing to bribery and telling how it worked, because they weren’t accused of bribery. Nealy and Fain didn’t flip. Nobody gave an inch.

Former U.S. Attorney for the Northern District of Texas Paul Coggins, now in private practice, compares this trial with two big previous federal trials of prominent African-American politicians in Dallas – the 2000 trial of Dallas City Council member Al Lipscomb, now dead, and the 2009 trial of City Council member Don Hill, believed to be dying of cancer while serving an 18-year federal sentence.

Coggins was U.S. attorney during the Lipscomb trial. He observes that both earlier trials, considered to be direct antecedents of the Price trial because of connected evidence, included testimony from guilt-admitting bribe-payers.

“It’s fair to point out that in the Dallas City Hall case [the Hill trial] you had the bribee being tried and the briber cutting a deal and testifying against him. In the Al Lipscomb case, you had the bribee going to trial and the briber pleading guilty and testifying against the bribee.” (Libpscomb's conviction was later overturned on appeal.)

Coggins says the government would always prefer to do it that way, in spite of credibility issues with bribe-payers who have flipped to save their own skins. At least that way, he says, “You do have the other side of the transaction cutting the deal.”No companies came to court confessing to bribery and telling how it worked, because they weren’t accused of bribery. Nealy and Fain didn’t flip. Nobody gave an inch.

tweet this

He suggests the government probably didn’t come to court in the Price trial without a flipped witness because it hadn’t tried to flip somebody. “There might have been a thought when they got into this that they were going to be able to flip one of these two women, either Miss Fain or Miss Nealy,” Coggins says. “And frankly, when that doesn’t happen, when they hang together, when they stick together, those are tough cases.”

But that leaves the other end of the stream, the original sources of the $1 million in illicit income the government claimed Price raked in over a decade. In the Hill trial, a rich white man took a guilty plea for bribery, then told the jury exactly how it had gone down.

The government brought some rich white people to the Price trial who confessed to things that certainly sounded naughty, as in paying Nealy to get Price to help them torpedo a much-needed economic development project in Price’s own district. But their testimony fell short of anything remotely criminal, and the government seemed disinclined to tug or push them over that line.

Former Dallas County Commissioner Maureen Dickey, herself wealthy, white and Republican, thinks that in concentrating on Fain and Nealy the government was squeezing the wrong end of the toothpaste tube. The people who were the original sources of the money, Dickey believes, might have been easier to squeeze.

Without pressure from the government, Dickey says, “They didn’t really have anything to lose. But if they had had something to lose, they wouldn’t have wanted to protect him.

“People like Dapheny just loved John Wiley. People didn’t realize how loyal folks could be to him, because he was such a charismatic character. But people who didn’t have any loyalty to him, rich white people, if they had been in any kind of jeopardy, they would have testified in a nanosecond to save their own skin.”"People who didn’t have any loyalty to him, rich white people, if they had been in any kind of jeopardy, they would have testified in a nanosecond to save their own skin.”

tweet this

Fain was found not guilty on the only two counts against her, for lying to FBI agents and for helping Price conceal income from the IRS. Nealy, who is charged with the same bribery and fraud charges that Price faced and defeated, is to be tried separately later.

Friday’s outcome draws sharply different reactions from different observers. Dickey, who sparred with Price when she was on the commissioner’s court from 2004 to 2012, says she is “saddened” by the not guilty verdicts, but she says she respects the jury for its long hard slog.

Michael Sorrell, president of Paul Quinn College, a historically black institution, does not sound saddened when he talks about the outcome: “I think it means a lot,” he says. “I say that because it has symbolic value on several fronts. First, from a historical perspective, you’ve not seen something like this before. You’ve not seen an elected official prevail, once this path was established. That’s not an inconsequential outcome.

“I think in terms of the lore of Commissioner John Wiley Price, this is another big chapter. In terms of sustained advocacy, we’ve not seen someone who has been this forceful, this impactful to so many people for so long.”

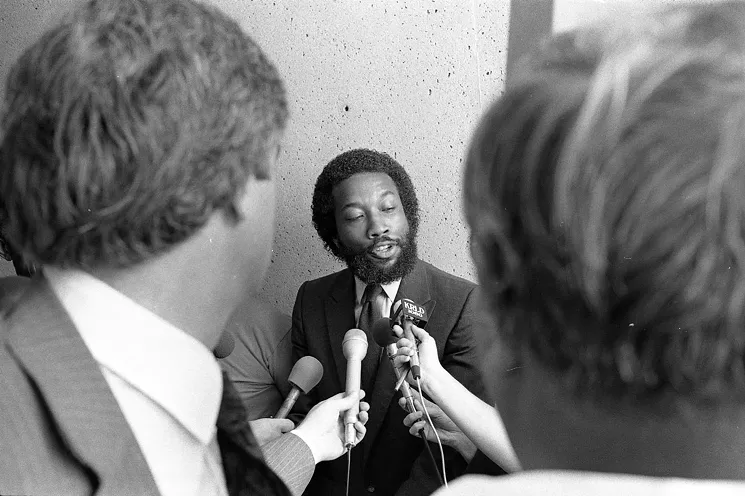

John Wiley Price speaks to reporters on June 23, 1981.

Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library

When he was a school kid, enough cotton was still hand-picked from the black clay fields around Forney to produce a large crop every fall, harvested mainly by black laborers dragging long sacks down endless rows. Most of those field workers were descendants of black families who had been ensnared in a system of debt-peonage from the end of slavery to the Second World War. On the farms around Forney in the 1950s and ’60s, the links to slavery were still direct, visceral and, when the fields were full, visual.

Price has told reporters over the years he remembers being hauled out of his segregated school in Forney every fall to work the cotton harvest with other black children while the white kids remained at their studies. Perhaps those memories shaped his lifelong conviction that hard labor was the wrong path forward for black people.

In 1985 in his first year as a county commissioner, Price said, “Black people in Dallas need to acquire capital instead of jobs. They need to recognize that you don’t own a job, a job owns you. But the route to doing that is through achieving true, full enfranchisement in the political arena and financial independence in the business arena.”

In 2009 Price used his position and power to stall a major shipping project called The Inland Port in his own district, even though the project promised tens of thousands of new jobs for Price’s own bitterly poor and chronically unemployed constituents.

Dickey remembers that chapter with particular dismay and bitterness: “I saw John Wiley do everything he could to keep the Inland Port from coming to fruition. I saw the Inland Port as a huge economic generator for Dallas County and the Dallas metroplex, and I saw it as a huge generator of jobs for the people of South Dallas, and I’m talking 30,000 or 40,000 jobs.”

At the time, Price voiced disdain for the promise of hourly wage manual work for his constituents, repeating the mantra he had expressed nearly a quarter century earlier: “During slavery,” he said, “everybody had a job. It all comes down to slavery. The nickname that most African-Americans call their job, they call it slavery.”

What he did not say but multiple witnesses testified to in the trial was that Nealy was being paid by interests associated with the wealthy and powerful Perot family, who control a rival shipping center, the Alliance Logistics Hub, in Fort Worth. Witnesses associated with Hillwood, a Perot company, testified in the trial that Hillwood viewed the Inland Port as a direct competitor and serious threat. They also testified that they had no idea Nealy was passing money on to Price and would never have considered hiring her had they known.

Price’s life story has always involved a love of money and a certain affinity for rich white people. In 1991 former journalist and Dallas Mayor Laura Miller wrote a profile of Price for D Magazine titled “The Hustler,” in which she described his early career after coming to Dallas in 1968 at age 18. Handsome and glib, he started off as a successful appliance salesman for a major department store. Soon he caught the eye of a white politician who got him a county job, and Price was in the thick of things.

Ironically, many of the traits and behaviors Miller marshaled in her portrayal of Price as a hustler could have been offered as exculpatory evidence in this trial to explain some of the wealth he has acquired while working for the county. As Miller conveyed, Price always loves hard bargaining, never buys anything at full price, always sells high and transferred those skills quickly from buying suits to buying cars to buying and selling real estate.

In Miller’s portrait, there is what could be taken as a contradiction: For all his disdain for hard labor as a way forward, Price has always been famously hard-working himself, a lifelong teetotaler, a predawn riser whose desk is stacked with technical papers and blueprints for his county road and bridge district, all of which he has read, understands and can quote from effectively in an interview or during a debate at the dais. As soon as he can get home in the evening he straps on a tool belt and works for hours rehabbing houses he has bought.

John Wiley Price meets with Dallasites in June 1981.

Dallas History and Archives Division, Dallas Public Library

His rich white admirers included mega-developer Dave Fox, now deceased, a stalwart of the private Dallas Citizens Council, who was county judge when Price first went on the commissioner’s court in 1985. Impressed with Price’s intelligence and charm, Fox told Miller he had hoped at one point to make Price the first black mayor of Dallas.

But whenever white men tried to make something of him, they soon learned Price didn’t want to be made – not by them. When he was still 23 and new in town he was picked out by white leaders for a flattering appointment to the board of a new black community center. But Price bit that hand by accusing his would-be benefactors of corruptly conspiring to suppress black influence over the center.

A second shot at white acceptance came a couple of years later when he was appointed by white leadership to another city board. Not long into that tenure, he was kicked off the board summarily after going to the FBI to report the city for vote suppression and fraud.

A consistent theme in his story has always been the interweaving of idealism with personal gain, not to mention the odd equanimity, almost approval, that his self-seeking has drawn from white mentors. Clearly his life has been a kind of secret key to the larger puzzle that is Dallas.

In her 1991 D Magazine profile, Miller revealed things that should have been enough to blow Price out of the water the day the story came out. On the barely legal but totally outrageous side, Price and Nealy for years engaged in a “consulting” business that Miller exposed, trading on skills Price had sharpened in flamboyant grass-roots campaigns against liquor companies and other entities he believed profited by oppressing black communities. In other cities far from Dallas, Price and Nealy worked the other side of the tracks. They hired themselves out to the rendering plant industry, for instance, to help shut down community opposition when rendering companies wanted to open new plants or allow old ones to keep burning dead dogs in black neighborhoods.

On what feels like the illegal side of things is a tale that seems like better evidence of corruption than anything in this recent trial – the saga of his career as a gas station owner. Price, then a county commissioner, bought an Exxon station with a partner. Price’s idea of salesmanship was going around to companies with large fleets that wanted to do business with the county and leaning on them to agree to gas up their fleets and have their vehicles serviced at his own Exxon station.

But Fox, the county judge who was Price’s would-be mentor, did not express anything like outrage when Miller revealed Price’s purchase of the Exxon service station to him and asked for comment. In fact Fox told Miller he had personally financed Price’s share of the station, and his only concern seemed to be that Price had been late with a couple of payments to him.

That embrace – the warm tight embrace of white money – was always there for Price, as it was always there for anybody else in town who had become prominent, acquired power or influence and also had the ability to cause problems. All a person had to do was play ball. White leadership wanted John Wiley Price and other young comers to be rich, happy and corrupt.

It was fine with them if he had his own service station and used it to bleed money out of county contractors. In fact they would finance it for him. He could make money selling out black neighborhoods to rendering plants. And he did. He took all the bait they offered.

The trick, the secret, the anomaly that was Price was this: He took the bait, but then he showed up a week later leading a protest in front of one of the city’s revered white institutions or businesses. And there was nothing ritual or fake about his protests. He went out there and literally kicked ass.

In the early 1970s when Price was just beginning to be a presence, Dallas was still decades behind the civil rights movement cities of the Old South. Major social and business events downtown were all-white except for wait staff. Black people averted their eyes and spoke to white people with a reserve that expressed fear.

In his street role, when Price was at the barricades in some new protest with news cameras rolling, he performed an often violent street theater that said, “This is how to be unafraid of white people.” His protests, always lavishly televised, frightened the socks off white people and brought cheers straight up out of the hearts of black people.

He was fearless. If somebody tried to push him out of the way with a car, Price leaped snarling at the windshield and snapped off the windshield wipers. One man made the mistake of trying to beat him up and wound up instead in a heap on the street with broken bones.

That was the part the white leadership could not control and could not ignore. By the time Miller interviewed him in 1991, Fox was already beginning to wash his hands, describing Price’s taste for confrontation as suicidal. It was the only explanation Fox could imagine. A black man who acted like that in Dallas had to be trying to get himself killed.

“It may be too late,” Fox told Miller sadly. “He may get his wish, if he has a death wish. He says he doesn’t. But if that’s true, then what is this?”

But Price did not die. He did not stop goading whites in public, nor did he stop flirting with white money behind the scenes. In fact that tempo quickened as Price’s power grew. White television audiences and newspaper readers who knew Price only through his public role couldn’t understand why he wasn’t already locked up or sent to hell. Meanwhile the white establishment figures who did nitty-gritty business with him were glad he was still around.

A few days before the end of the trial, a prominent white Dallas businessman, speaking not for attribution because he is in a business that depends on local government, recalled being sent 20 years ago as a student to attend a speech Price was giving at the university where he was an undergraduate:

“My dad said to me, ‘You have to understand, John Wiley Price is a role that Mr. Price plays in public and that he thinks he has to play to achieve his ends. But we know him as a really good guy and a smart man that you can deal with. You need to know him.’”"John Wiley Price is a role that Mr. Price plays in public and that he thinks he has to play to achieve his ends. But we know him as a really good guy and a smart man that you can deal with."

tweet this

Price’s view of white people is idiosyncratic. Tom Mills, who was Fain’s attorney in this trial, was the lawyer in 1996 for the only other local official anyone could think of this week who beat a massive federal mail fraud case in Dallas. It also happened to be a federal case in which nobody flipped.

The late Dan Peavy, a school board member, was charged in 1996 with taking $459,000 in kickbacks from an insurance broker who became his co-defendant. Neither man turned on the other, and both were acquitted.

The year before his trial, Peavy, who was white, had been audio-recorded by a neighbor who listened in on his cordless telephone calls. When the recordings went public, they included foul-mouthed racist ranting by Peavy. Mills says now, “Dan would say many racist things. Nigger. Bad, bad stuff.”

A week before Peavy’s mail fraud trial was to begin, Mills ran into Price, whom he had known for years. Mills says, “He said, ‘I love Dan.’ I said, ‘Why?’ He said, ‘I love Dan because Dan tells the truth. He’s a racist. The people I hate are white people who say they’re not racist but they are.’”

Price agreed immediately to testify as a character witness for Peavy. Mills then purposefully kept five black jurors on the jury, including one who became foreman. He said Price came to court and repeated what he had told Mills about Peavy.

“He said, ‘He’s an honest man. He would not commit mail fraud. He’s absolutely a racist. But he tells the truth. All white people are racist. But Dan tells the truth.’

“The jury found him not guilty of 42 mail fraud counts.”

Somewhere in the complex moral bargain Price has struck with himself, he has earned the overwhelming approval of his constituents, who elect and re-elect him by mile-high margins no matter what he is accused of, no matter what’s going on behind the curtain. In southern Dallas, John Wiley Price is politically bullet-proof.

In the trial, prosecutors ripped back that curtain and showed Price and his associate, Nealy, helping the wealthy white Perot family of Dallas sabotage the Inland Port. In his closing argument to the jury, Assistant U.S. Attorney J. Nicholas Bunch explained carefully and explicitly how Price had worked to stall a special tax district designation that the Inland Port project in his own district needed in order to go forward:

“Commissioner Price engineered pulling it from the agenda,” Bunch told the jury. “Commissioner Price’s actions delayed this from the fall of ’06 to March of ’08. He met with the Hillwood folks and told them he was pulling it from the agenda.

“Why did he do that? Because Kathy Nealy was on retainer at Hillwood.” Bunch told the jury Price sabotaged the Inland Port, “despite the fact that this development going forward in his own district would have brought significant economic growth.”

In the pews at the back of the courtroom while Bunch spoke, two luminaries of local black history, the Reverend Zan Wesley Holmes, pastor emeritus of St. Luke Community United Methodist Church, and former City Council member Diane Ragsdale both appeared to be soundly asleep.

Former County Commissioner Dickey says she is saddened by the verdict because of the moral damage she says she has seen Price wreak on county government. “Otherwise good people that worked for the county were doing things that I think were unethical or illegal, because they made a devil’s choice.”

She says Price’s influence on county government has been a dark force coercing good people to do bad things. “I think they were under a huge coercion. A lot of them are people I know were good folks. I really feel sorry for those people, because they were under a great deal of stress. It’s not fun to have to do things that are probably against your ethics all the time.”

She calls the loss of the Inland Port project, as it was initially envisaged, one of the worst economic and social blows ever suffered by the city. “This would have been the nexus of trade for the United States,” Dickey says, “and we threw that away by letting a politician and political influences keep that from happening. I see that as a huge betrayal of the city of Dallas and the people who supported Commissioner Price.”

Sorrell of Paul Quinn College finds a very different way to look at this outcome in particular and at Price’s role in the history of the city generally:

“I think when we really stop and analyze the contributions that John Wiley Price has made to our city and our county, you absolutely have to ask yourself if he isn’t one of the five most influential leaders in Dallas of all time.

“I think if you’re capable of performing that analysis from an impartial standpoint, just measured on impact, there is no way you don’t come out thinking that the answer isn’t just yes, but you struggle to come up with five people who have been more impactful.”