Jesse Bernal

Audio By Carbonatix

The witches, or at least those among them who called themselves that, gathered under tents lining the side streets of Denton’s downtown square selling handcrafted wares – jewelry, plant terrariums holding foraged animal bones, paintings, homebrewed teas, elixirs and baked goods. Tarot card readers offered spiritual insight through cartomancy or by breaking down astrological charts, while others waited in line for craft cocktails by the Hemlock Fox mixologist.

This was the Beltane celebration at the Every Witch Way (EWW) market, one of the eight Pagan sabbats celebrating the peak of springtime and heralding the coming summer. The market, next scheduled for Oct. 14, prides itself on being “an intersection of all spiritual paths” open to anyone with an interest in the mystical and magical.

But you won’t find any pointy hats here, nor broomsticks, bubbling cauldrons or hexes for sale. There was one cauldron at the event, but the only things swirling around inside it were raffle tickets to win a gift bag from EWW’s sponsor and Denton’s resident metaphysical shop, Bewitched.

Founder Elizabeth Bernal watched over the raffle cauldron when she wasn’t floating among the vendors’ tents, checking on how they were faring in the heat and helping to hold down tent poles against sudden gales of wind, her close-cropped, electric-blue hair gleaming under the afternoon sun. Nearly two years ago, she put out a call to local practitioners of witchcraft and mystical arts in an attempt to find others like her, or perhaps build a coven, if you will. She thought maybe there would be enough people to fill a shopfront on the sidewalk. Instead, she was flooded with vendor requests, and submissions have held strong for every market since.

This is just a small sampling of the growing population of neo-pagans, Wiccans, witches and other revived folk magic traditions. An exact count of self-identified pagans and witches is difficult to determine, but Italian Catholic-witch and author Antonio Pagliarulo estimates that he is one of over a million Americans practicing the craft, as he wrote in an op-ed for NBC about witchcraft making a comeback. As of last fall, #WitchTok videos on TikTok have accumulated over 30 billion views as creators and users share modern methods of witchcraft and find community among their kind.

Pam Grossman, practicing witch, author and host of the Witch Wave podcast, attributes the uptick in mystical and occult interest to people looking for alternative sources of empowerment during a period when many are mistrustful of institutional power structures. In this digital age of spending so many hours in a day in front of screens, the embodied, sensual experiences of witchcraft help people find a sense of connection missing from their lives, according to Grossman.

“Witchcraft is incredibly embodied as much as it’s about spirit and visualization,” she says. “It’s also about connecting with the earth, connecting with the cycles of the seasons, of the body, all of these highly sensory and natural experiences of what it means to be human.”

Each new wave of feminism over the last few centuries has brought with it a rise in the occult, as Grossman points out. Witchcraft has ancient, divinely feminine associations dating back to the earliest incarnations of the figure Lilith in the Sumerian civilization and goddesses across other early human mythologies, like Hecate of ancient Greece. Since the women’s marches of 2017, the latest wave of feminists has been rallying around cries, “We are the daughters of witches you couldn’t burn,” and, “Hex the patriarchy.”

Powerful as those slogans are, they don’t quite capture the dark underbelly of witch history that still impacts people today. Including my own family.

My maternal ancestors were charged and tried as witches during the Salem Witch Trials of 1692. Two escaped prison and fled for their lives, eventually returning to Salem once the hysteria had died down. But Bridget Bishop, my ninth great-grandmother, was the first to be executed by hanging on June 10, 1692.

A memorial for Bridget Bishop, the author’s ancestor, who was tried and executed as a witch in Salem.

Darby Murnane

Despite the trove of TV shows and books exploring alternative, dramatized histories and versions of Bridget’s character and her descendants, she was not a witch. She was a woman trying to survive until she couldn’t.

The idea of witches can be empowering for those, like me, who have felt othered and outcast. The witch is a powerful and defiant character who stands as a symbol of rebellion against oppressive forces and a manifestation of one’s own internal power. But the word “witch” comes with a massive body count that continues growing to this day.

The mysterious, romantic allure of witchcraft in this modern era does not erase the lethality of accusations. Experts estimate 40,000-50,000 people were murdered during European witch hunts between 1450 and 1750. In the 20th century alone, the death toll of killings related to accusations of witchcraft is believed to have surpassed that of all the combined 300 years of European hunts. In Tanzania alone, 40,000 accused witches were murdered between 1960 and 2000. In 2021, the United Nations passed a resolution condemning witchcraft accusations around the globe.

“When you think of witches, you think of your society’s conception of women,” says Rachel Christ-Doane, education director at the Salem Witch Museum in Massachusetts. She calls witchcraft a “gender-related crime, but not a gender-specific crime.” From 75% to 80% of the victims during the European hunts were women, and the majority of those killed today are women. Still, almost a quarter of victims in the past were men.

I traveled to Salem, Massachusetts, two summers ago to see the memorials dedicated to the victims of the trials, the site of the executions and the graves of the magistrates who signed Bridget’s death warrant. She was arrested on April 18, my birthday 306 years later. That might as well have been the day she died, because the moment her arrest warrant was signed and the irons clapped around her wrists, Bridget was no longer a person to the court, her neighbors and her accusers. She was a heretic, a monster and a blight to be eradicated.

Today, Salem makes about $140 million every year off its reputation as “Witch City” and the so-called “dark tourism” industry that’s sprung up around haunted tours and occult shops. There’s a fine line between remembering the massacre of the trials and romanticizing the violence behind the city’s infamy. As a journalist, I ponder the ethics of how the stories of the trials and the victims are told, of embracing the title of “witch” among those who practice the craft. My ancestress was murdered because of the word, and had my other relatives at that time not escaped, I would not be here. I don’t want to undercut the innocence Bridget died trying to defend or that of women still shunned as witches in today’s world.

Still, I understand the pull to that narrative. Part of the appeal of witchcraft is the decentralized nature of the practice without hierarchy. Grossman is fond of saying that the craft posits that we are all magical beings and anybody has access to this power because it exists inside of all us. But as with most faiths, it also serves to connect practitioners with something greater than themselves, which Grossman calls the “capital S, ‘Spirit.'”

“That Spirit is in us and in everything,” she says. “But it’s also something I believe we have a responsibility to.”

To understand the positives of what modern witchcraft has to offer and gain insight into the local witch community, one need to only turn to the founders and co-organizers of the EWW market.

When Natalie Kirby was 7 or 8 years old, she fell on the way to school one morning, shredding her palms and knees. She had already walked almost four blocks away from the house and sat alone and bleeding, dripping red all over the white, chalky gravel of the empty country road. But within five minutes, her grandmother found her and patched up Kirby’s wounds. Her grandmother knew Kirby was hurt, the same way she knew a lot of things, just like Kirby’s mother.

The women in her family call it “the knowing.”

“We all have it, Kirby says. “I imagine it’s like being dialed on the same radio station.”

To the Kirby women, the phenomenon was as a natural and practical as their menstrual cycles syncing up. Kirby’s mother fell in with the New Age cultural movement of the late ’70s and early ’80s and raised her daughter with a wide sampling of mythologies and beliefs from around the world.

Kids at school often asked Kirby, “Is your mom a witch or something?” Every time, she and her mother would roll their eyes and say, “What a bunch of dorks.”

“We didn’t have these labels, the way everything’s labeled now,” Kirby says over coffee at the West Oak Coffee Bar. “That was not really the way. I would say if we had a magic, it was telling our stories to each other.”

With EWW, Kirby reads tarot cards and astrological charts. She calls herself a tarot storyteller instead of just a reader. She doesn’t claim to tell fortunes from the cards or tap into some unseen knowledge to which only she has access, but insists that those who come to her already know on the inside what they see in the cards – they just need permission to put the pieces together. For her, the market represents a community of misfits and rejects making a home together.

“That’s fundamentally how the witch stuff really became the ‘other,'” she says. “What we’re made up of is a bunch of others.”

Cassie Smith, a Hemlock Fox mixologist and special events/community outreach coordinator for the market, believes that true magic lies in authenticity.

“The more true you are to yourself, the more magic you’re going to have,” she says. “But if you aren’t learning to like that authentic part of yourself, you’re not ever going to be able to tap into that magic.”

Smith grew up in a Baptist family, attending a small church where her grandfather was a deacon. But she didn’t see her family upholding the morals and beliefs they espoused in church on Sunday. The hypocrisy she perceived didn’t sit right, and she never felt connected to the Christian faith.

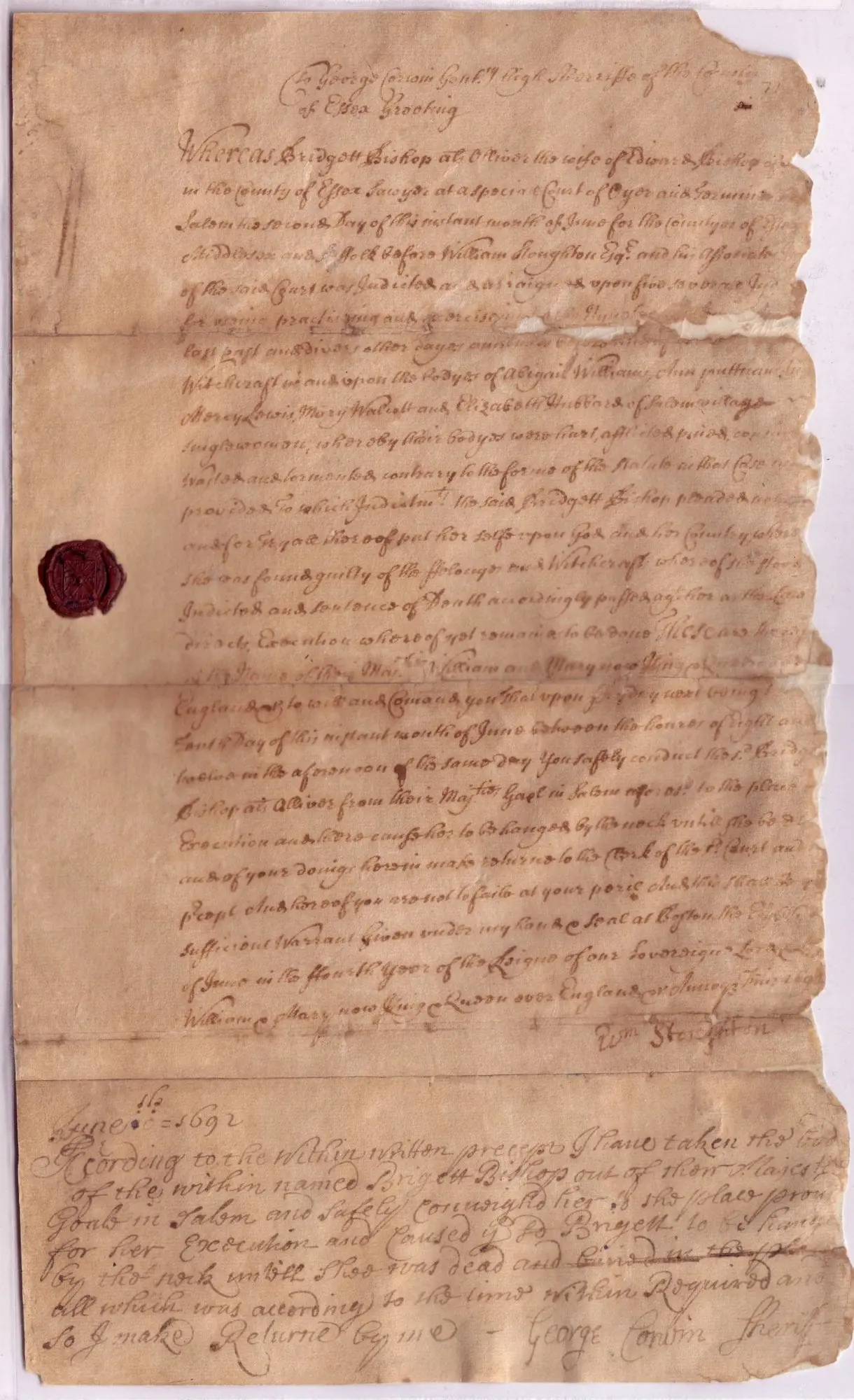

Bridget Bishop’s death warrant from the Salem Witch Trials.

Darby Murnane

“I felt much more in tune and connected to nature,” Smith says. “Anytime I was around trees or plants, I felt much more myself; I like that magic within me.”

She considers herself more of a green witch, one who cultivates the earth and practices with nature. Smith is an avid gardener and grows all her own herbs and fruits that she uses to make her Hemlock Fox cocktails. Her mixology is a form of her craft: working with natural ingredients to concoct her boozy potions.

Like Smith, Bernal also grew up in a devoutly Baptist community and rebelled against the social constraints of its teachings as a teen. She remembers causing a small scandal at school when she was the only one to refuse to sign a virginity pledge to stay abstinent until marriage. But at home, Bernal was surrounded by “magical thinking,” reading books about fairies and making wish boxes. Even her grandmother’s cooking process was magical in its rituals.

“My grandmother would roll over in her grave, though, if she knew that this is what I do for a living now,” Bernal says with a laugh.

In conjunction with the market, she runs a small business called Woolen Witch Crafts. Bernal forages animal bones from nature and uses them to make ethereal home décor, such as vintage lamps suspended from preserved vertebrae. She also sells woolen animal familiars as keepsakes, and some filled with catnip as toys for pets. Despite the consistent presence of witchcraft in her life since childhood, Bernal felt a deep discomfort around Pagan spaces for years until she understood the feeling of excitement and curiosity for the unknown and unfamiliar. Stepping into that world, she says, was like coming out of the broom closet.

“The minute I gave in to that, that’s when things kind of started to fall into place,” she says. “That’s when I was like, it’s fine that I’m different. Let me just play to my strengths instead of trying to hide them and trying to do what everybody else wants me to do or things I ‘should’ be doing.”

Grossman doesn’t think it’s necessarily unique to witchcraft that when we see ourselves in others’ work, it can feel like a “bit of a permission slip to be even more truly ourselves.”

Christ-Doane, from the Salem Witch Museum, remembers growing up in the ’90s exposed to the explosion of witch characters in popular media and seeing the witch become a coming-of-age symbol, particularly for young women.

“It’s this idea that you’re going to wake up one day and realize you have superpowers and you felt different your whole life, and this is the reason why,” she says.

Most marketgoers and vendors have come to EWW with much of the same gratitude and generosity Grossman has witnessed on a national level in response to her work.

“The vast majority of people who encounter my work … have felt as if they are being given some kind of affirmation about things they know to be true about themselves,” she says.

Despite the threats some Pagan and witch festivals or gatherings have faced in recent years from the religious right scrabbling for footholds among the changing social landscape, EWW has received a mostly warm and eager welcome from the DFW community. A handful of people have approached Bernal with rude comments or declared, “You don’t look like a witch.”

She only replies, “What does a witch look like?”