Nick Metzger

Audio By Carbonatix

7:30 p.m. Wednesday: Updated to include the resolution between the band and Nick Metzger.

Nick Metzger is a local business owner, a part-time DJ and a self-described “vintage audio enthusiast.” About eight months ago, he put up an ad describing some items he was looking to buy: “Reel-to-reel players, tapes and other vintage hi-fi gear,” he remembers, though he doesn’t recall whether it was on Craig’s List or OfferUp.

A man responded, saying he had some old reel-to-reel players to sell, and Metzger made arrangements to come by the man’s house, “somewhere in the mid-cities,” to take a look. Metzger bought three of the players but found something far more interesting: a collection of 50-75 old tapes that had belonged to one of the former owners of the Band Factory, a recording studio in Fort Worth that went out of business in the early 2000s.

Metzger says the seller “seemed pretty uncaring about the whole thing.”

“He said something like ‘Oh, yeah, we used to record all kinds of bands back in the day. You’ll probably find jazz, country, rock, blues, who knows what,'” Metzger recalls.

“You have to remember he hadn’t seen any of those machines or tapes for probably 10, 15 years at least,” Metzger continues. “He only had them in his house because his former business partner left them to him in his will.”

The seller told Metzger that he (and specifically his wife) wanted the tapes out of the house.

“He had left the studio life to go be an IT technician, or lawyer, or something completely different than working in a music studio,” Metzger says of the man, “so I think to him it all just represented his ‘former life,’ and he didn’t seem to have any sentimentality about it. That was just my read on the situation.”

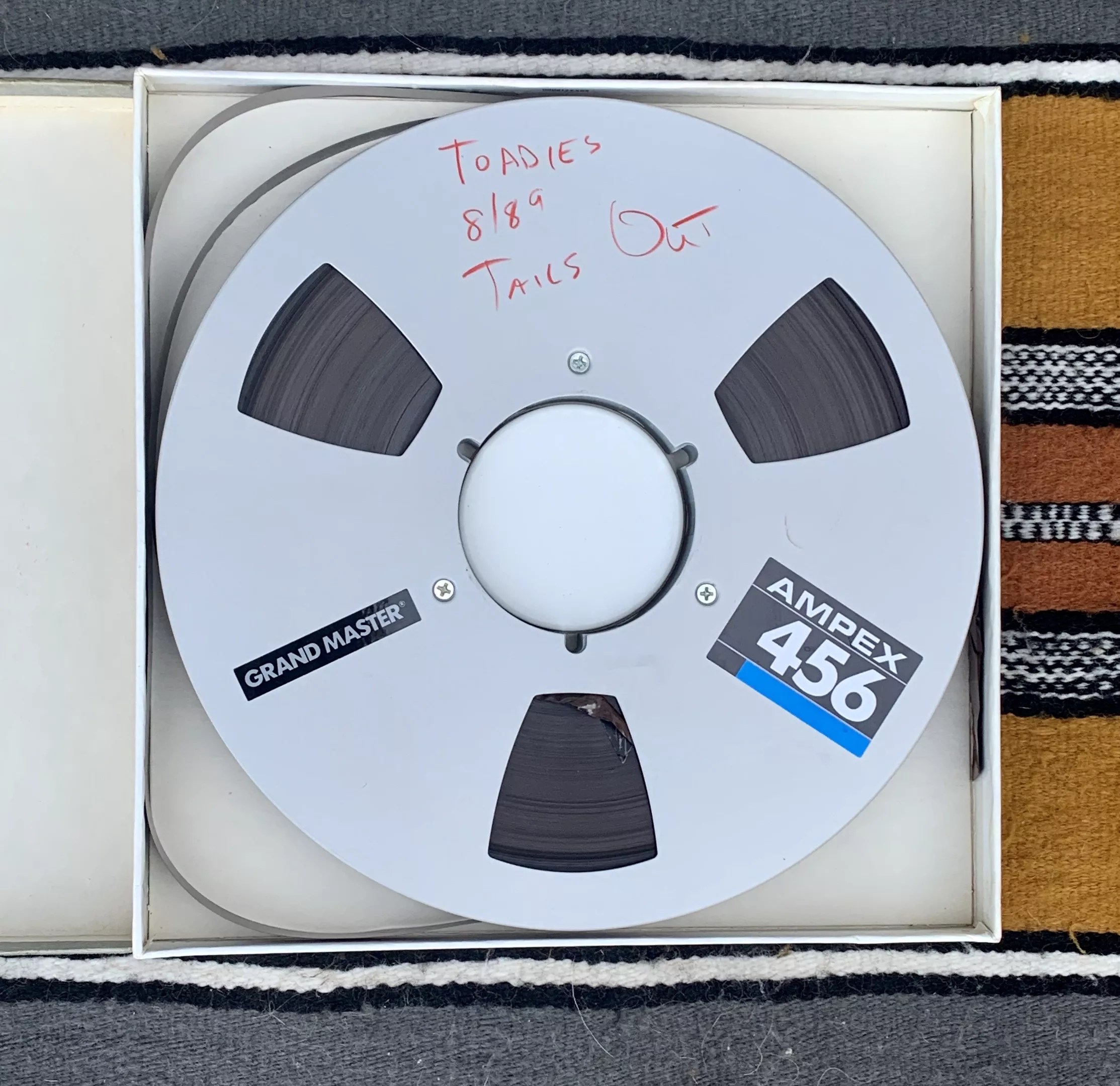

Metzger pored through the tapes and found most of the recordings were from unknown bands, emulating the sound of rockers like Rick Springfield. He found one shiny bit of treasure, however: a recording from 1989 by the Toadies, a DFW-based band that was hugely popular in the ’90s and is still a successful touring band.

The master tape includes four tracks off the band’s first EP, Slaphead, one of which, “I’m Away,” was re-recorded as “When I’m Away,” in the Toadies’ hit 1994 album Rubberneck.

“Obviously I was excited when I found the Toadies tape,” Metzger says. “All monetary value aside, I think it’s a really important piece of DFW music history, and to unearth something like that is really special. And I guess you could even argue a really important piece of rock history as a whole.”

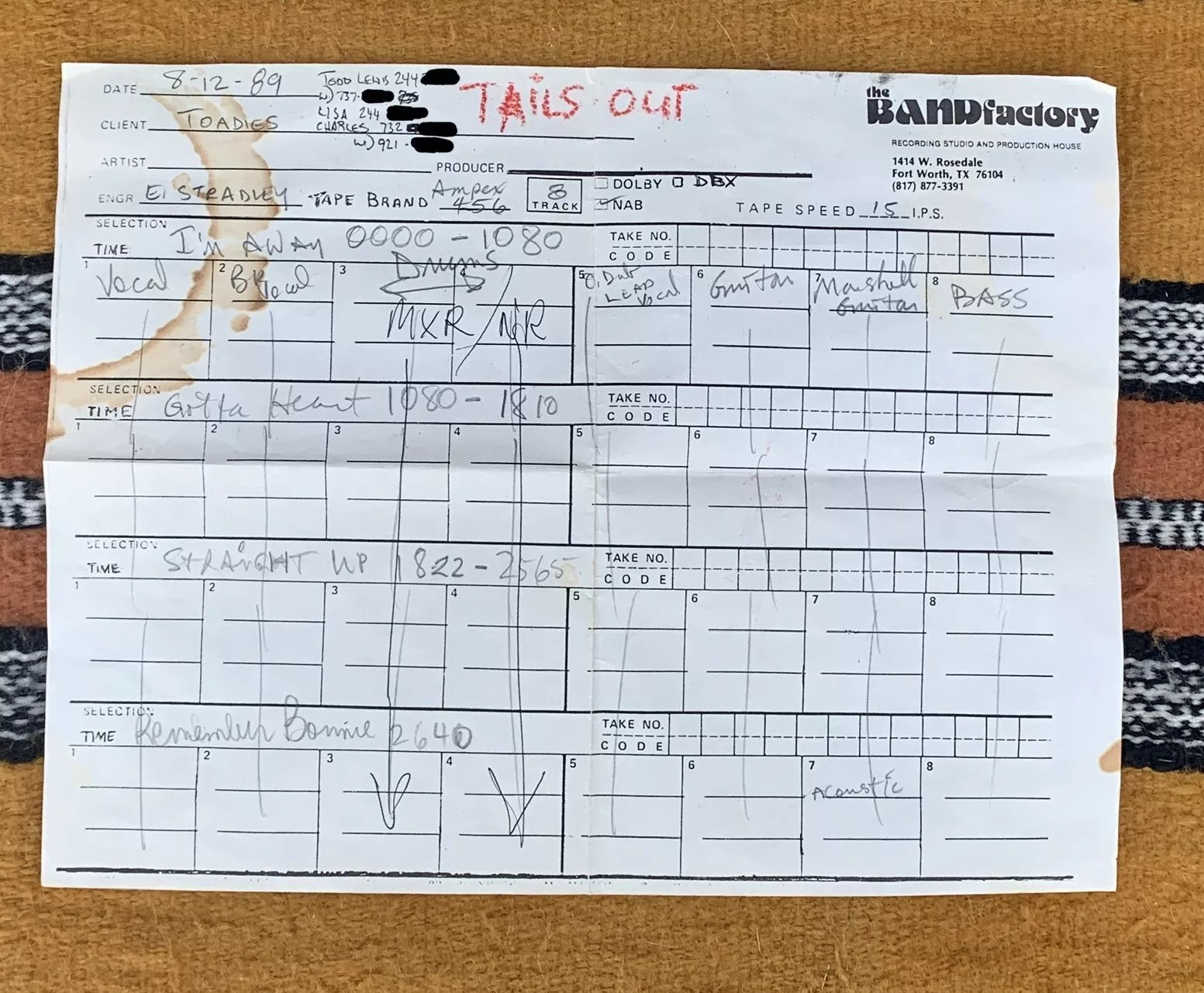

The tape is a 1/2-inch eight-track. It came with a tracking sheet from the studio, which notes each track’s instruments and vocals, and has a list with the band members’ names and phone numbers.

Metzger says he contacted Vaden Lewis, the band’s lead singer, on Aug. 4.

“I contacted him under my wife’s Facebook account because she’s friends with him on Facebook and I’m not,” Metzger says. “I sent him a few pics of the tape and sheet, gave him a mini explanation of the situation and said I’d love to talk to him about it if he was at all interested. I gave him my direct cell number as well.”

Metzger says he made no mention of money in that message, “because I just wanted to talk.”

He says Facebook noted that Lewis had read the message, but Metzger says when the singer didn’t reply he made other plans.

“I figured he didn’t care,” Metzger says, “So I went along with listing the tape on eBay.”

“All monetary value aside, I think it’s a really important piece of DFW music history, and to unearth something like that is really special … And I guess you could even argue a really important piece of rock history as a whole.”– Nick Metzger

This past weekend, Metzger put up the tape for auction on eBay. “This is an incredible piece of history in its own right,” the listing read. “It even has Vaden Todd Lewis, Lisa Umbarger, and Charles Mooney’s (presumably old) phone numbers on the sheet!”

In the listing, Metzger explains that each track is on an individual channel: “For instance, vocals are one track, drums are one, bass is one, etc. If you want to listen to this tape in its full glory you will need an eight-track reel to reel machine like a Tascam 80-8 or Otari MX5050.”

He also explains on the listing that he went to a friend’s house to hear the tape and confirmed that it was a legitimate recording. “It’s especially cool because you can hear the band members talking and chatting in between track takes,” Metzger wrote on the description.

On Aug. 15, Metzger says he heard from the Toadies’ management.

“I got my first message from an eBay user who presented herself as Tami the manager of the Toadies,” Metzger says. “She said she would be happy to pay the ‘buy it now’ price of $200 for the tape. I responded the $200 was the starting bid for the auction and not a ‘buy it now’ price. I then quoted her what I thought was a very fair buy-it-now price for a band the size and prominence of the Toadies.”

Metzger says he heard back from Tami Thomsen, who represents the band, on Monday.

“She sent me a much more terse email telling me my offer was both quote ‘unreasonable’ and, quote, ‘not cool.'”

Thomsen, Metzger says, “further explained that she believes the band retains full copyright of the tape and in essence, my procurement of the tape was somehow illegal or unauthorized.”

Thomsen says the band was willing to give Metzger some compensation for his find but was not willing to match his initial offer.

“I saw the listing over the weekend, too,” Thomsen tells the Observer in an email. “I messaged Nick then and let him know that the band would like the tape. … After all, it is theirs and they have already paid for it once! I offered Nick his eBay starting price of $200. He replied back that he would ‘accept $3,000.'”

“It’s our belief that the studio didn’t have the right to sell it to Nick and that Nick doesn’t have the right to sell it to anyone else,” she wrote. “I’ve sent him a second note attempting to sort it out reasonably between us. If he continues with the sale we will be turning it over to our attorney. We would ask Toadies fans/anyone else not to bid on the item.”

Toadies frontman Vaden Lewis playing Rubberneck’s 25th-anniversary show at Southside Ballroom.

Andrew Sherman

The band declined to comment.

“To respond directly to Tami’s accusations, I would like to, as respectfully as I can, claim that she’s wrong,” Metzger says. “I did not procure the tape from the studio directly. By the time I procured the tape The Band Factory Studio had been out of business for at least 10, 20 years. I bought the tape from a private individual who worked at the studio in its early days, but was not even an employee of The Band Factory when it closed in the ’90s/early 2000s. The only reason he had it was because of an estate inheritance from the death of his former business partner.

“I’m certainly not a copyright lawyer but copyright is not simply a matter of who originally sang/played on the tracks – as we have recently learned from the Scooter Braun/Taylor Swift master tape debacle. If it was only a matter of who sang on what tape, then Taylor Swift would have been given her tapes back by the courts the same day,” Metzger says.

Last year, non-musical people learned the meaning of “master tapes” through persistent headlines about Swift’s legal fight for her own body of work, which was bought by Justin Bieber’s manager Scooter Braun when record label Big Machine sold off the rights to her catalog. Swift claimed she had not been given a chance to buy her masters, and instead had received an offer from Big Machine to “buy back” the masters of her first six albums if she signed a 10-year contract with the label.

Despite her resources, legal efforts and widespread support, Swift famously lost the case.

“The commercial distribution rights remain with the Toadies and/or Vaden Todd Lewis,” Metzger says. “Whoever owns the tape, including myself, could not legally duplicate it and sell it for commercial profit. Those rights remain with the singer/songwriter/band, et cetera. However, the original physical media is a different story. Owning an original piece of physical media with no intent to commercially distribute is well within the law.”

While Metzger doesn’t plan on publishing the songs, he says, the Toadies would be within their right to do so if they acquire the masters, which Metzger believes have the potential for the Toadies to make a larger profit.

“The Toadies may think the ‘buy it now’ price I quoted them is unreasonable and uncool and, again respectfully, they can have that opinion,” Metzger says, “but let’s be honest, once they have that tape, they’re more than likely going to take it into a studio, remix it, remaster it, and release it via digital and physical media. And whenever COVID ends they could even take those songs and create a tour or show based on them.

“In other words, they will almost assuredly make money on the songs,” Metzger continues. “To ask a band as big as the Toadies for a reasonable compensation for finding their master tape that they can turn around and monetize does not seem unreasonable nor unfair to me. I don’t think I even have to mention the Toadies have toured the world and played for hundreds of thousands of screaming fans at festivals and events. They’re not exactly some unknown bar band that never left Fort Worth.”

George Gimarc, a longtime radio host, music archivist and historian, has found and sold many master tapes, including recordings by Glen Campbell, Steve Vincent and Hank Williams. With the latter find, which was particularly rare, Gimarc consulted an “expert on all things Hank,” who approached the singer’s estate. The group worked together to get the album released. Gimarc was satisfied with his compensation, and mostly with the fact that the album won a Grammy in 2015. Gimarc was one of the recipients, as the academy listed him as a “researcher,” he says with a laugh.

He says Metzger’s story is a “pretty standard tale.”

“There are record collectors and music archivist like myself that find things,” Gimarc says. “There are some of them who will try to get them to market, and some of them will do it legitimately.”

Gimarc says that many buyers seek to make a profit of bootlegging themselves, or by selling it to someone with that end goal. Or, that tapes could go back into obscurity.

“And they’ll sell it for the highest price to a collector who wants to have that trophy of saying I have this unique song in my collection that nobody else does, and they get a good price, and then it disappears down the rabbit hole into somebody else’s collection and it never sees the light of day, and the fans never know it exists,” he says.

Gimarc estimates that he has 300 to 400 master tapes, “Some of which were abandoned with me.” He now holds or is negotiating the sale of tapes by Steve Miller, Freddie King, Peter Frampton, The Ramones and a Neil Young demo from 1967.

“I tried to place this on two compilations of Buffalo Springfield,” he says of the Young tape, “and, you know, Young stuff over the last 20 years, and both times Neil has swatted it down. He didn’t want the song out there … because it’s kind of clear he’s ripping off Bob Dylan in the song. I think it was a little embarrassing.”

Gimarc says that while he doesn’t know the specific legalities of the Toadies tape, he estimates its worth at “at least four figures.”

He doesn’t find Metzger’s ask of $3,000 excessive.

“It’s called a negotiation,” Gimarc says.

“Technically speaking, he doesn’t have the right to press them, to duplicate them, to do anything, except he could sell it as a collectible,” Gimarc says. “[Toadies] have the publishing rights on writing, even the performance rights, but [Metzger] actually owns a master, and they ought to be happy that he does, because if he got to where this whole thing got too heavy for him he might sell it to a collector in Japan, and then they go real hard. … That could happen, and they wouldn’t have anything. They couldn’t do anything about it.”

Ownership can be hard to determine, Gimarc says.

“That can vary greatly,” he says. “And things get a lot more wiggly when it’s going back a couple of decades and nobody’s got a paper trail.”

Ultimately, he believes that unless the musicians can prove their masters were stolen, it’ll come down to a “finders keepers” rule.

“It’s called a negotiation. “– Music historian George Gimarc

“I would think possession of the tape counts,” Gimarc says.

His protocol, Gimarc says, is to first make contact with the band. He occasionally will contact bands with releases he’s found and return them in exchange for lunch, but that’s when the value of their tapes is more sentimental than monetary.

He’s personally had disputes over ownership during past sales, like with an old Beatles release. He also notes a famous case in which Paul McCartney took an old school friend to court when he tried to sell an early Beatles recording of a Buddy Holly cover of “That’ll Be the Day.”

“Paul McCartney went after him … with the 8,000-pound sledgehammer legal team that Paul McCartney carries, and the result was the guy had to give the tape to McCartney,” Gimarc says. “And this is a guy who was just one of the lads from Liverpool. He didn’t have any money and he gets bullied by his old friend Paul, and he saved this thing,” Gimarc says of the record.

“He’s kept it, he’s treasured it. He’s kept it safe for decades when it was abandoned by the Beatles. And there’s a ton of us out there in the music world who think that McCartney was just was such a bastard for doing that because he could have easily thrown this guy a really decent chunk of change for hanging onto this.”

Gimarc thinks the Toadies are “lucky” their tapes are in the hands of Metzger and not a label like Universal.

“They’re negotiating with an amateur at this point, so they ought to realize they are lucky to be doing this because the tape could fall into the hands of somebody who just wants to screw them. This guy’s clearly not doing that,” Gimarc says of Metzger. “At minimum, you could say this thing’s been in a storage vault for 20 years. They paid $100 a month for that storage, $1,200 a year, times 20. What’s the storage fee to keep this thing safe? Somebody paid that.

“The Toadies just need to freakin’ chill out,” Gimarc says. “They ought to be thrilled that the thing exists and it didn’t end up in the trash. Most of this stuff gets trashed.”

Metzger says that, for now, he has removed the listing from eBay and is unsure about his plans for the recordings.

“I decided to end the auction because I am not interested in a protracted legal fight,” he says. “The Toadies have made it abundantly clear they are interested in the tape, and I am happy to make a deal with them for the return of their tape. As a gesture of good faith I reduced my asking price to a number that would be well within the budget of even a struggling band, of which I know the Toadies are not. If they accept my offer I will return the tape.”

Metzger still takes offense at the band’s unwillingness to negotiate and says he was made to feel “like a criminal,” when, he says, he found the tape in good faith.

“I must note the hostility and outright rudeness I received from Toadies manager Tami Thomsen, who has sadly sucked the joy out of what I was hopeful would be a fun and joyful moment in DFW rock history,” he says. “During our one and only phone conversation this afternoon, Tami verbally berated me and more than insinuated that I was some kind of criminal who illegally stole something from the band.”

Like Gimarc, Metzger says master tapes often go missing or get damaged in storage.

“I can imagine a lot of bands who would be thanking me profusely for rescuing their master tape,” he says. “… The Toadies were lucky that I was the one who found the tape because I was able to recognize the historical significance and did my best to contact the band prior to listing it on eBay. It’s disheartening to me they don’t recognize that and are treating me like an enemy.”

Update:

Metzger says he and the band have come to a resolution via a third party.

“My friend has a close relationship with [Toadies label] Kirtland Records, and he offered a compromise solution to satisfy both myself and Toadies management,” Metzger says. “My friend and I negotiated a fair payment for the tape this evening and we made the exchange. My friend has pledged to immediately donate the tape to Toadies management/Kirtland Records as a gift… I’m happy both parties could come to an amicable solution and I could play my small part of DFW rock history.

“I want to thank both Toadies management and The Toadies themselves for contacting me and coming up with an amicable solution for both parties. The matter has been fully resolved,” Metzger says.

The studio notes that accompanied the tape include the band members’ old phone numbers.

Nick Metzger