Meredith Lawrence

Audio By Carbonatix

The death of Botham Jean, a 26-year-old accountant and innocent man, and the trial of his killer, former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger, have challenged Dallas as no event since the 2016 murders of five police officers in one terrible night downtown. Now as then, a big part of this new challenge will be for Dallas to keep its head on straight.

In the wake of an extraordinary display of remorse by the convicted defendant and of forgiveness by a member of the dead man’s family, Botham Jean’s mother, Allison Jean, and her civil lawyers are insisting that Dallas still has a steep price to pay. They would know. They are the ones who will be paid, if they are able to overturn a decision issued a month ago by U.S. Magistrate Judge Irma Carillo Ramirez tossing out their wrongful death lawsuit against the city of Dallas.

The reasons cited by Judge Ramirez in dismissing the suit go straight to the argument that the death of Botham Jean was the fault of the city. Her order directly contradicts the claim in the suit that Jean’s killing was part of a pattern of racist police oppression in Dallas.

In federal court a magistrate judge’s decision is sort of a recommendation, not necessarily binding on the federal district judge who eventually will review it. When this gets to that level, the matter could go the other way, and the lawsuit could be green-lighted to proceed.

In the meantime, however, the residents of the city need to keep in mind that there is a context in which the plaintiffs in this litigation make public allegations. For example, in a speech immediately following the jury’s decision to sentence Guyger to 10 years in prison, Allison Jean specifically addressed key points in the Ramirez order without acknowledging she was doing so, especially the question of training.

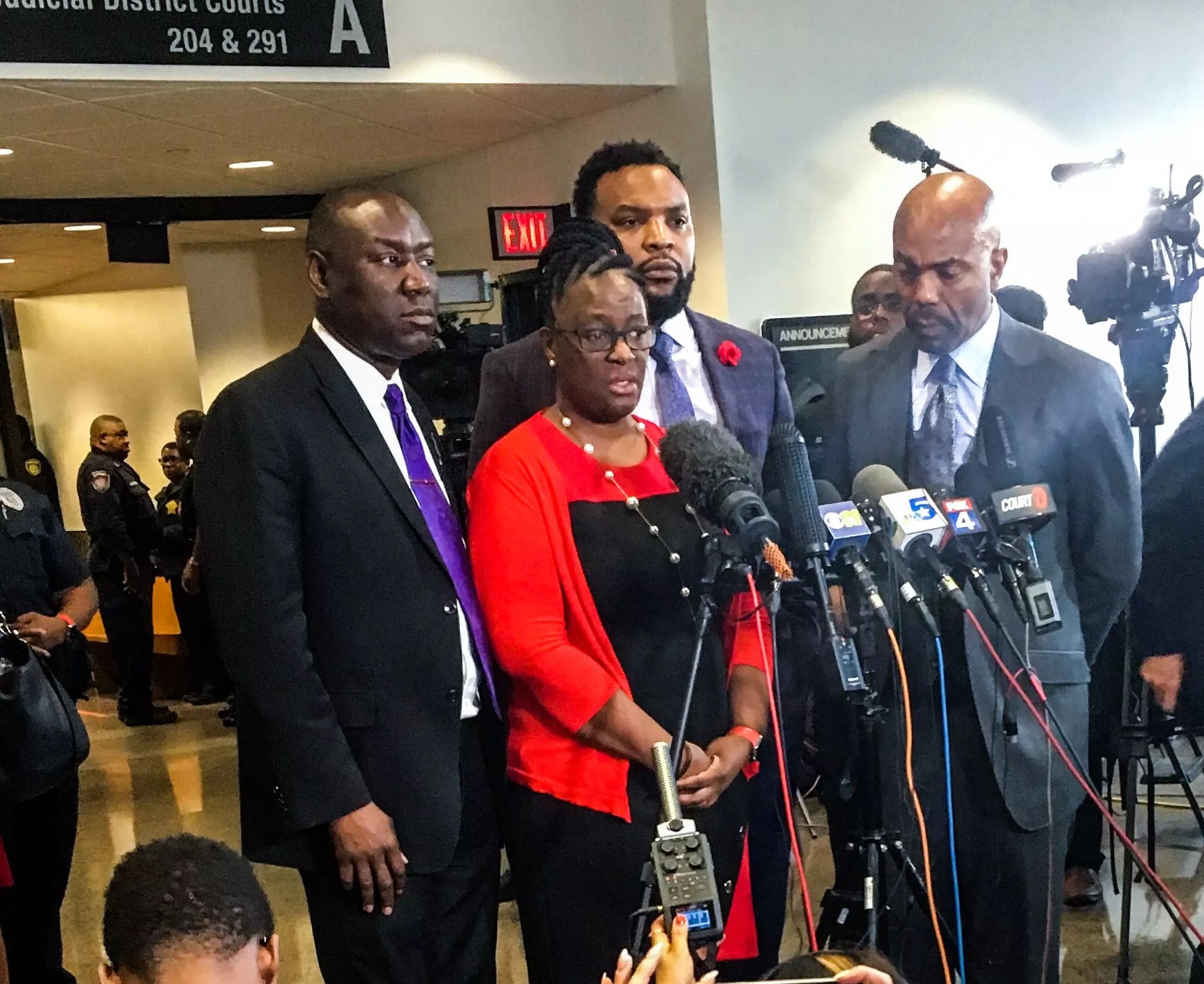

With her three civil lawyers at her side, Jean spoke to a battery of reporters: “The poor training or the poor use of what should have been training is what we see coming out of this case,” she said.

“That should never ever happen again. And if this was applied in the way it ought to have been taught, my son would have been alive today.”

Police training is the key hurdle in the way of the Jean family’s lawsuit. Under the magistrate’s order, the training question is what stands in the courthouse door barring their entry.

“The poor training or the poor use of what should have been training is what we see coming out of this case.” — Allison Jean

As Ramirez recites in her order, Dallas, as a municipality and creature of the state, is immune from suit except under certain conditions, one being a policy or pattern of behavior that deprives people of their constitutional protections. Grinding that down a little finer, Ramirez points out that bad police training, lack of training, bad police policies or bad patterns of behavior all have been a windows in the past through which litigants have successfully penetrated the fortress of municipal immunity.

Put simply, if the cops are depriving people of their rights on purpose and as standard operating procedure, the city can be sued for it. It doesn’t have to be an official policy on paper. It’s just what they do.

The problem for these plaintiffs, Ramirez found, was that they didn’t come close to establishing the policies or the patterns sufficient under existing case law to justify suspending the city’s immunity.

The complaint filed by the Jean family cites seven incidents in a four-year period when Dallas police officers shot unarmed minority people as a result, the plaintiffs allege, of “the lack of training and official custom or policies of the DPD.”

In her order tossing the lawsuit, Ramirez said the cases cited by the plaintiffs did not constitute a discernible pattern of behavior by Dallas cops because they did not fit with the Guyger case. Most of the seven were cases in which police had confronted suspects who struggled with them, presented other resistance or tried to escape.

“Although the cases cited by Plaintiffs and Defendant involved shootings of unarmed minority individuals by police officers, they are not ‘fairly similar’ to Jean’s shooting inside his own home. None of these cases involved an off-duty officer approaching what he or she believed to be a burglary taking place in his or her own home at the time of the shooting,” Ramirez wrote in her order.

“Because these other incidents relied upon by Plaintiffs are distinguishable from the instant case and do not establish a pattern, they are insufficient to show a custom or policy supporting municipal liability under the theories of failure to train, supervise, or discipline.”

And it gets worse for the plaintiffs. Ramirez says further that, even if the cases cited by the defendants did fit more closely with the facts of the Guyger case, seven still wouldn’t be enough:

“Even assuming for purposes of this motion only that the seven prior incidents Plaintiffs cited are similar enough to reasonably infer a pattern sufficient to establish a custom or policy of insufficient training, supervision, or discipline by DPD because they involved unarmed minority individuals shot by police officers, the incidents occurred over a four-year period between 2012 and 2017.

“Accordingly, they are not ‘sufficiently numerous’ to demonstrate a pattern sufficient to support such a custom or policy.”

In her order, there are quote marks around “sufficiently numerous” because it’s a quote from another important earlier court decision. She’s not working from her own hunches. These questions about training have been ground down to a pretty fine powder by the courts in earlier precedent-setting cases. There are specific standards for how many instances are enough to establish a pattern, and Ramirez says what the plaintiffs are offering here doesn’t get close.

The Jean family’s lawyers offered the court a workaround. It’s called the “single incident exception,” and it applies to a case in which bad training may not be a department-wide problem but the training in one particular instance is bad enough to make it an issue. And, again, remember that the plaintiffs have to make training an issue in order to get back into the federal courthouse.

But again, Ramirez shoots them down. She says in her order that under existing case law, “the exception is generally reserved for those cases in which the government actor was provided no training whatsoever.”

Former Dallas police officer Amber Guyger, 31, shot and killed 26-year-old accountant Botham Jean, mistaking his apartment for her own.

Nathan Hunsinger

The hail Mary in the lawsuit – a claim repeated by the prosecutor in the criminal trial – is an allegation that official Dallas police policy and training are fake, anyway. What Dallas says officially and on paper does not reflect, the plaintiffs allege, what Dallas really teaches its cops and wants them to do. Instead, the plaintiffs claim, the real Dallas policy is, “Shoot first, ask questions later.”

“Although the cases cited by Plaintiffs and Defendant involved shootings of unarmed minority individuals by police officers, they are not ‘fairly similar’ to Jean’s shooting inside his own home.” — U.S. Magistrate Judge Irma Carillo Ramirez

But as Ramirez lays out in her order, the law has a highly developed system, almost a machinery of precedent designed to precisely measure that exact claim. In a city of 1.3 million people with between 2,500 and 3,000 cops on the force at any given moment in time, an actual policy of “shoot first, ask questions later” should show up at a certain rate over time.

Even if we accept the seven instances in four years cited by the plaintiffs as fitting a pattern with Guyger, which Ramirez does not, we’re still way short of the number needed to prove a pattern, she says. And taking Guyger alone, as Ramirez does, we have only one instance.

I think we’re allowed a certain common sense here. If the real policy of the Dallas Police Department is to shoot first and ask questions later, then the vast majority of the city’s cops must be disobeying orders all the time.

On the other hand, we wouldn’t want to use the statistical problem here as an excuse for callousness. If there were only seven instances of minority citizens in four years shot and killed by racist white cops, would that mean we shouldn’t care? We’re off the hook?

And does Allison Jean not have a right and a moral duty to ask that her son’s death have meaning? Mrs. Jean and the whole Jean family carried themselves with a wonderful intelligent dignity throughout this awful saga, and Dallas owes them a great debt for that.

But as I said at the top, Dallas also owes it to itself to keep its own head on straight. We have to recognize that there is an ecosystem out there – I do not include the Jeans because they’re not from here – made up of people with a vested interest in convincing us we have made no progress on institutional racism since a white cop murdered 12-year-old Santos Rodriguez here 46 years ago.

That’s not just absurd. It’s obscene. In the Guyger trial, a black judge presided before a majority-minority jury while a white cop was prosecuted under the regime of a black Dallas County District Attorney, in a city with a black mayor.

In Santos Rodriguez, all of that picture was inside out. All of the authority was white. The white district attorney promulgated a written book of instruction for his staff on how to keep minorities off juries. Printed. Distributed. Without an ounce of shame.

Owning the progress we have made as a city does not mean we are done. Allison Jean spoke truth when she said Dallas has a long road ahead between this moment and justice.

But in this case, denying the progress we have made may be cynical. And in a larger sense, dismissing real progress would dismiss the reason for working toward progress. It would devalue the pain, courage, suffering and generosity that have pulled us forward from that moment almost a half-century ago to this moment today.

Dallas properly has a lot on its conscience right now. But Dallas also has a lot for which it must be justly proud. The challenge of this moment will be keeping all of that straight.