Mike Brooks

Audio By Carbonatix

Maria Childs was fleeing an abusive relationship when she entered a Fort Worth homeless shelter called Safe Haven. She stayed there as long as she could, 30 days, before she had to move to Austin Street Center, a shelter in Dallas. She had no income, and health problems like a pacemaker and a bad knee kept her from working, but she needed a way out of the shelter. Childs, 71, was able to enroll in a program that would help cover her rent at an apartment in Northwest Dallas for a year.

Her time in the program hasn’t been the best, and now that it’s nearly up, she’s not sure where she’ll go next. The carpet in the apartment she was placed in was a mess. She had bed bugs, and maintenance requests wouldn’t always be answered in a timely manner.

That program is part of a regional initiative called the R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing Initiative, which has a goal of rehousing 6,000 homeless people by 2025. R.E.A.L. stands for Responsible, Equitable, Accountable and Legitimate. The initiative has seen some success, housing more than 2,700 people in two years. The idea is that people in the R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing Initiative will reach some form of self-sustainability once their rental subsidy runs out and their case management is up. That can happen in a number of ways: it could be by reconnecting with family or finding a good job or getting set up with the right assistance to help pay the rent.

But some participants end up in apartments with poor conditions, don’t get the support they need to become independent and are left wondering where they’ll go next.

At first, Childs didn’t completely grasp the finer points of the program. She thought she would be receiving a permanent housing subsidy, not a temporary one like rapid rehousing offers. “That’s how we understood it,” she said.

The organization set her up in an apartment in Northwest Dallas in February 2022. It was far from Child’s doctors, but it was one of the only places the organization could find for her. She said the choice was either to take the apartment or start all over in the system. She was unable to see the apartment in advance, and although she thought she was moving into a one-bedroom unit, she was placed into an efficiency instead.

Lisa Marshall started Fighting Homelessness to help people navigate the housing system.

Mike Brooks

She didn’t like the place, partly because it was far away from her doctors. She told her caseworker that, but it seemed the apartment was the only option. “I told them I didn’t want to stay here. They go ‘Well, you either stay here and move into this apartment or we can’t help you,'” Childs recalled. “I had no choice because I had nowhere else to go.”

So, she signed the lease. She said the carpet was filthy in her apartment when she first set foot in it. The air-conditioning unit was also too loud for her, and the landlord threatened to evict her for asking someone to check it out. She called her case worker, and eventually Childs got a window unit installed in her apartment. But one day she came home to find water on the counters and on the floor.

She said it took days to fix. The water in her apartment was starting to smell, so she stayed at a neighbor’s unit for a couple days, sleeping on their couch. It took several attempts, but the maintenance team at the apartment complex was finally able to fix the leak. “It shouldn’t have taken that long,” she said.

As time passed, more problems presented themselves. One week, the apartment complex didn’t have hot water. There was also a problem with bed bugs in her unit, and she would wake up with bites all over her. Childs initially thought it was mosquitos biting her in the night. But one night as she went to bed she saw little brown bugs crawling along the side of it. “I thought to myself, ‘What the heck is that?'” she said. She looked it up on her phone, and it appeared to her that they were bed bugs.

The next morning she went to her landlord to tell her about the bugs and ended up throwing all of her bedding away and replacing it. The landlord accused her of bringing the bed bugs from the shelter and tried to make her pay for the exterminator to come out and take care of them. “I was going to have to pay $365,” she said. She ended up not having to pay for the exterminator.

Childs’ lease is up on Feb. 12, with a requirement that she give notice in December if she isn’t going to renew it. Her case worker asked if she planned to re-sign the lease.

“I said ‘There’s no way I’m going to pay $1,295 for an efficiency,'” Childs explained. “I can go somewhere else and probably find one better than this place.”

She’s currently looking for a new apartment with help from her brothers, the local organization Catholic Charities and homelessness advocate Lisa Marshall. She’s also considering moving in with a roommate.

To Childs, the rapid rehousing program has been fine in most ways. It’s allowed her to get on Social Security and save up for a new place to live. She would have gotten on Social Security sooner, but she thought she’d be going back to work until her health worsened. Her current living situation is an improvement over where she was not all that long ago. But, she added, her case worker is supposed to come check on her once a month, and she’s only seen her about three times since she’s been in the program. She said she’s called her caseworker repeatedly over the last couple of weeks, but she hasn’t gotten an answer.

While things will be tight, Childs thinks she can make it on her own now, but she’s less sure about others in the program.

“There are all these people that are going to have to move, and they don’t know what they’re going to do because they don’t have the income to pay for it,” she said. “So, I don’t know what some of these people are going to do on housing.”

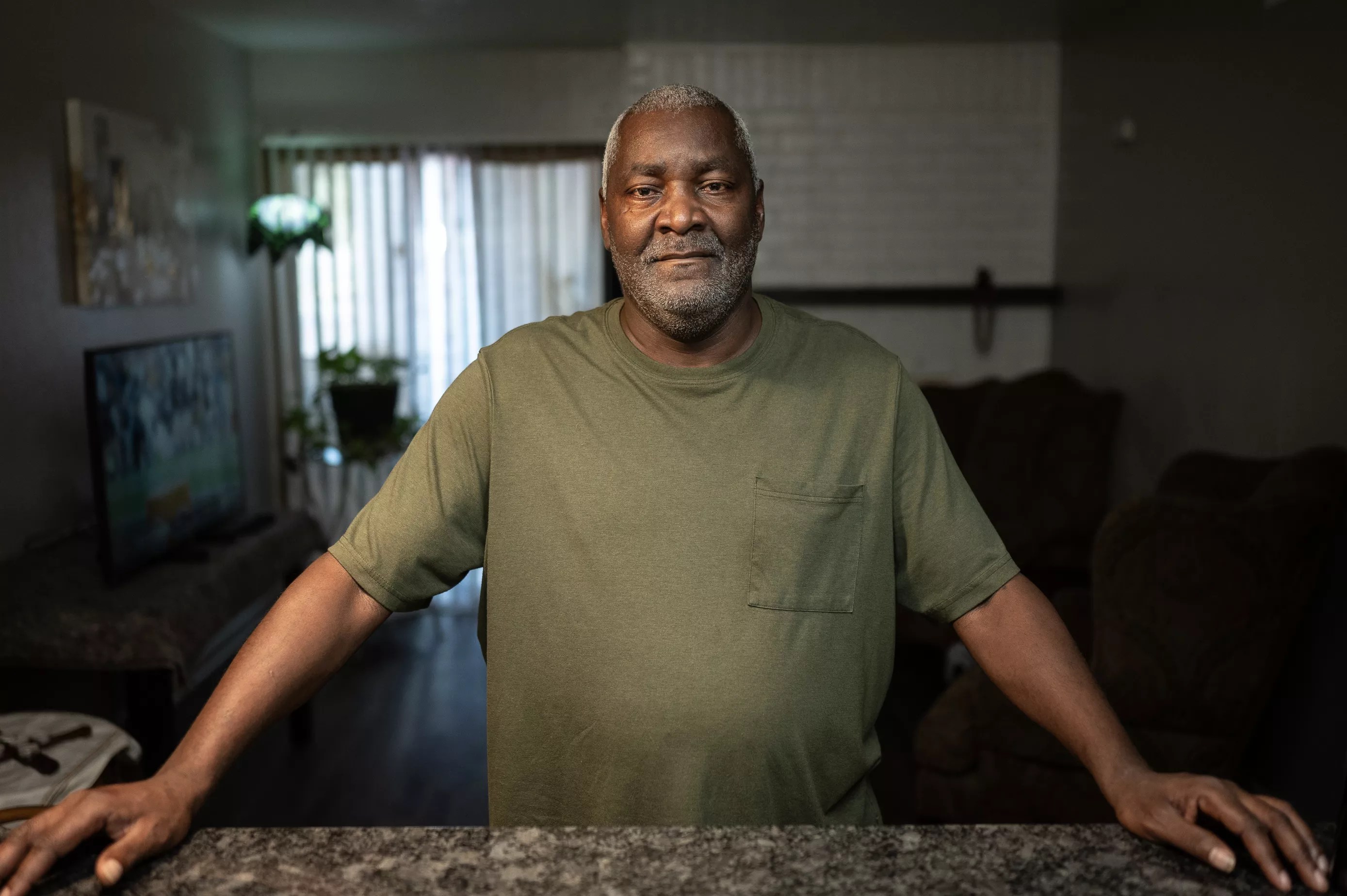

Kevin Harrison is unsure about his future

after his housing subsidy runs out.

Mike Brooks

While the R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing Initiative has had success with rapid rehousing, this intervention isn’t for everyone and it doesn’t always work. A 2021 article in the journal Housing Policy Debate identifies some issues with rapid rehousing as a cure for homelessness.

The article dives into a rapid rehousing program in Salt Lake County, Utah, where about 70% of people in the program obtain permanent housing within three months, but some 10%-50% become homeless again within two years. Participants noted several reasons, citing medical emergencies, unreliable or low-paying jobs, transportation issues, criminal charges and substance abuse as factors that made it difficult to stay in housing.

Kevin Harrison, 60, who also participates in the local R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing Initiative, isn’t sure what will happen to him when his rental subsidy runs out. For him, the experience with rapid rehousing has been positive so far. Before joining the program, Harrison was bouncing from shelter to shelter.

“It’s better than where I was at,” he said.

Most recently, he stayed at Austin Street Center. Before that, he lived at St. Jude’s Senior Center off Forest and Josey lanes. And before that, he lived at The Bridge, another shelter in Dallas. Today he’s living in a one-bedroom apartment partially paid for through the rehousing initiative. Because he receives about $915 per month from Social Security, he has to put 30% of his income toward rent, about $274.

He moved to Dallas from Phoenix in 1995 for a home-remodeling job, but when the job was complete he had trouble finding employment. His money ran out and he soon found himself hopping from motel to motel and, eventually, shelter to shelter before getting on rapid rehousing. He now suffers from a lung disease called sarcoidosis, which prevents him from working.

When his time in the program is up he’ll have to re-sign the lease or find another place to go. If he doesn’t, he could end up right back in the shelter. He doesn’t suspect he’ll be able to stay in his current apartment because he won’t be able to pay for it without a subsidy. He said his case worker is helping to ensure he still has a roof over his head when his lease is up. The program has allowed him to put some money away, but it will likely never be enough to pay for another apartment, he said.

“It is what it is,” he said. “There are a lot of people out there that need more help than I do.”

If he has one criticism about the program, it’s that people should be given more than a year to get back on their feet.

“There are all these people that are going to have to move, and they don’t know what they’re going to do because they don’t have the income to pay for it.” – Maria Childs

“That’s not a lot of time,” he said. “There are some people out there that don’t have income. … And a lot of people are in bad health, so they really can’t work. Or they’re trying to get their Social Security or disability or something. They’re trying to get started within that year’s time and by the time it does kick in, it’s time to move.”

Asked how many people remain housed after being on a R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing subsidy, Housing Forward’s CEO Joli Robinson said Dallas and Collin counties are above the national average. Housing Forward is the lead agency for the homeless response system in the two counties. Robinson recently announced she’ll be leaving the organization to become CEO of Chicago-based Center on Halsted, a service center for the LGBTQ community in the Midwest.

“The national average for any program is about 80% remain housed, and we know that we are above that from the last quarterly report,” Robinson said. “We try all we can so that the system isn’t just churning people back out into the homeless response system.”

Even so, some 18% of participants end up reverting to homelessness. The statistic is worrying to Lisa Marshall, a local advocate who started an organization called Fighting Homelessness. She’s concerned that some people are being put on rapid rehousing when they should be given a permanent housing subsidy.

Marshall questions how people like Childs and Harrison will get by on their own with the cost of living as high as it is.

“I get it. You want people off the street,” Marshall said. “We don’t want to see them homeless on our streets. That’s the message. So, get them in rapid rehousing. Get them into housing. Get them stable. They’ll be all better.”

According to Marshall, the problem with that line of thinking is that “there’s no safety net for when the money’s gone.”

Paula Baines is excited about rapid rehousing.

Mike Brooks

Paula Baines, 54, is determined not to be part of that 18%. She’s in a rapid rehousing program run by the local organization Under 1 Roof, a group that is also part of the R.E.A.L. Time Rehousing Initiative. Baines is in her second month in the program after moving into a place in East Dallas called The Flats on Bryan in October. Before The Flats, Baines had been staying at Austin Street Center since January. She’s excited about rapid rehousing.

“I feel at peace,” she said. “This gives me the opportunity to start from the ground up and work my way up to where I can be, and I’m grateful for the opportunity.”

Baines had just been kicked out of her apartment, and she didn’t know anything about rapid rehousing when she started living at the Dallas shelter. “I did not have anywhere else to go,” she said. “I was just that, seeking shelter.”

She moved into her last apartment on her own in December 2021. But the complex was sold, and during the transition, she didn’t sign a new lease. She paid month-to-month even though she was already having trouble covering her rent. Luckily, she was able to get rental assistance from the county and nonprofit organizations, which prevented her landlord from evicting her.

The rent payment during the lease term was $981, but it went up to $1,720 on a month-to-month basis under the new ownership. Once her rental assistance ran out in November 2022, her landlord kicked her out.

This is what brought her to Austin Street Center, where she was assigned a personal caseworker from January to May 2023. She was put through an interview process to determine what assistance she qualified for and what the best match was for her. Under 1 Roof was that match.

She was in the shelter from January through the first of October, and it was an experience she will never forget. Baines now knows a thick skin is needed to make it in a homeless shelter.

“Shelter life is not for the weak. Homelessness is not for the weak,” she said. “No one ever plans to be homeless. No one ever plans to go to a shelter and basically have someone to tell you what to do – when to go to the bathroom, when to eat, when to stand up, when to go through this door, what time you need to be back from this door. … It’s a totally different animal. I totally understand why there are people that would rather be out in the elements versus in a shelter.”

“Shelter life is not for the weak. Homelessness is not for the weak.” – Paula Baines

Under 1 Roof set her up with another case worker and moved her into The Flats. Her case worker is willing to help her in any way she needs, but the main focus now is returning to school so she can get her degree or some certifications. That way she might be able to get a good job and pay for an apartment on her own. But she’s not sure if she’ll be staying at The Flats. “To be honest, I personally know that I will not be staying after this year because the cost of the rent is insanely expensive and it’s unrealistic,” she said. Her rent is $1,640 a month.

She’s two classes away from a bachelor of arts degree in communications. Communications, radio and television is where she has always wanted to work, although her employment history is primarily in customer service.

“The degree that I can obtain will open up doors,” she said. “I’m so close, I could touch it.”

Her place at The Flats is a one-bedroom, one-bath unit with a full kitchen. Under 1 Roof also supplied her with a dining room table, a couch and a queen-sized bed. She doesn’t get along with management, but other than that she doesn’t have any complaints about the apartment.

While she was in the shelter, she heard horror stories about rapid rehousing. She talked to people who said they’d been in three rapid rehousing programs and returned to the shelter after each one. She’s confident she’ll eventually be able to make it on her own, but these conversations gave her doubt. “It was discouraging, honestly,” she said. “That made me think this is a one and done, meaning I will not be homeless again ever in life. Never again.”

She thinks she could pay for something closer to the $1,300-$1,400 range. The days of paying under a thousand dollars for rent are over, she believes. “Things have changed,” she said. “Money has changed. The cost of living is different.”

If she’s going to pay $1,640, which is what it costs at The Flats, she’d like something like a townhome. Her apartment at The Flats is nice, but it’s basic, she said, and certainly not worth $1,640. She said she’s willing to consider a roommate, but she’d rather live on her own.

Asked how she feels about the future, she said, “I have no choice but to be optimistic.”