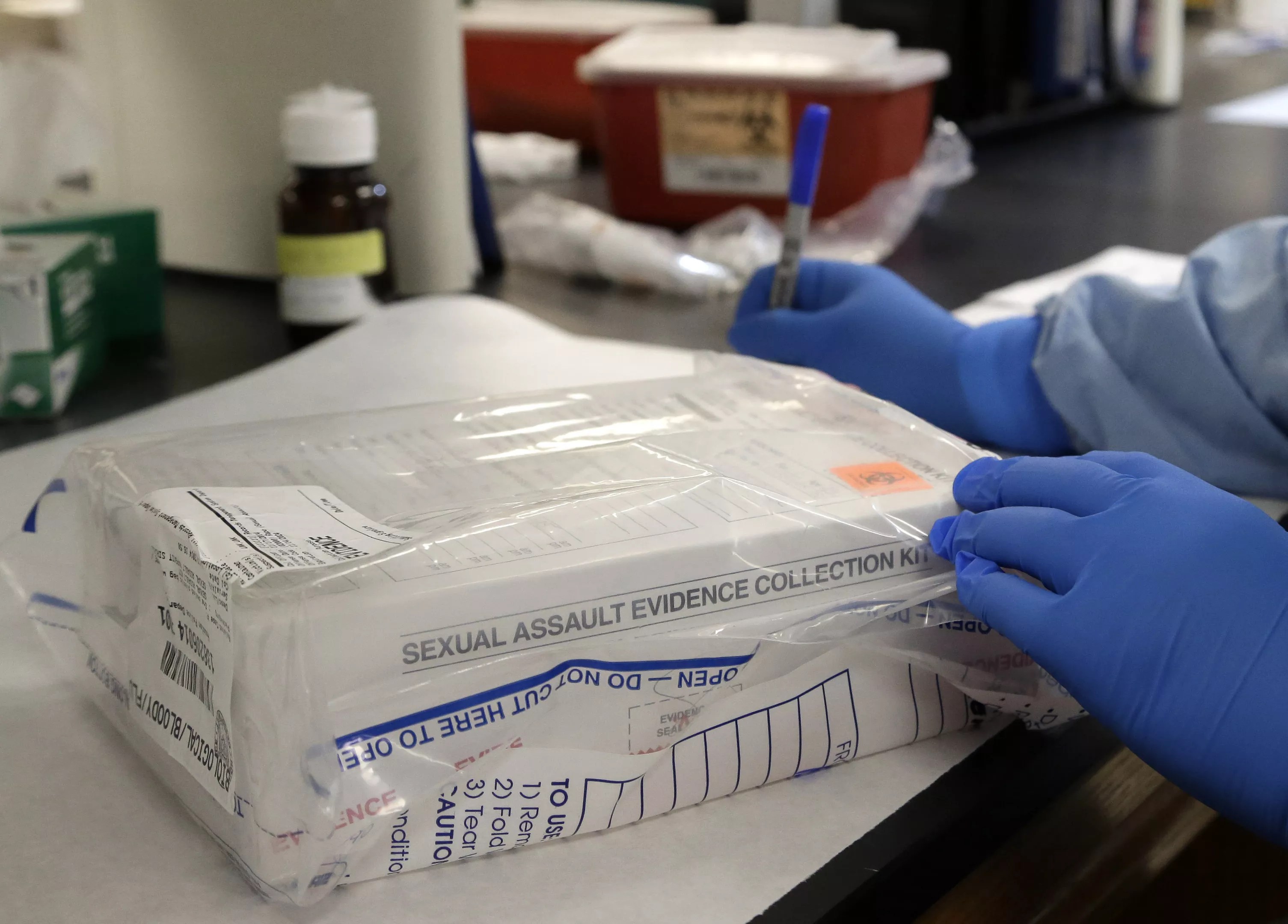

AP Photo/Pat Sullivan

Audio By Carbonatix

A year ago, the number of untested sexual assault kits in Texas, and especially in Dallas, was rather staggering. The pandemic, staffing shortages and a lack of funding were the primary reasons law enforcement agencies, including the Dallas Police Department, gave for the backlogged kits reaching into the thousands.

To think of the catastrophic emotional impact a sexual assault has on the life of one victim is nearly unbearable. Multiply that by thousands and add to that the search for answers and, possibly, closure for each victim with their name on an untested kit, and it was a problem of titanic proportions. In 2021, it was reported that Dallas had the largest backlog of untested rape kits in the state of Texas.

Over the course of 2023, however, a certain amount of progress has been made to reduce the number of untested sexual assault kits throughout Texas and in Dallas. That’s thanks in part to $2.3 million approved by the Dallas City Council in December 2022 to test the backlogged kits.

In Dallas, the backlog was divided into two groups. One group is sexual assault kits from 1996 to 2011, which are being tested at Virgina-based lab Bode Technology and paid for by federal grant funds. The other group consists of kits from 2011 to 2019 that are being tested locally at the Southwest Institute of Forensic Sciences (SWIFS).

Will you step up to support Dallas Observer this year?

At the Dallas Observer, we’re small and scrappy — and we make the most of every dollar from our supporters. Right now, we’re $14,500 away from reaching our December 31 goal of $30,000. If you’ve ever learned something new, stayed informed, or felt more connected because of the Dallas Observer, now’s the time to give back.

At the beginning of 2023, there were 1,880 sexual assault kits waiting to be tested between the two backlogs. According to an email from a spokesperson with the Dallas Police Department, all of the kits in the 1996-2011 backlog were sent to Bode Technology for testing in 2023, and all of the kits from the 2011-2019 backlog have been sent to SWIFS for testing, leaving the DPD shelves empty at this point.

In 2022, the Observer published a feature that examined why so many untested sexual assault kits (SAK) had piled up across the state. That was the same year that more than 14,000 sexual assaults were reported in Texas, according to the DPS. Even with House Bill 8 having been signed into law in 2019, there were many thousands of untested sexual assault kits in Texas when our 2022 article ran.

“I know we’ve come a long way and I applaud that, I’m grateful for that, but still, I don’t see the excuse of having any kits on the shelf.” – Lavinia Masters

HB 8, also known as the Lavinia Masters Act, was designed to address the backlog throughout Texas by dictating a timeline for SAKs to be tested and for the kits to be preserved throughout the period covered by the statute of limitations. But the sort of progress that Masters, the law’s namesake, had hoped to see in the first few years following the bill’s enactment had yet to be made as 2022 ended.

Masters was raped in her Dallas home in 1985 when she was 13. She waited for more than 20 years for her SAK to be processed before her case was finally reopened, only for the statute of limitations to have already passed. Her attacker went on to commit other rapes. For years prior to HB 8 becoming law, Masters campaigned for sexual assault kit reform, lobbying the state government and becoming an advocate for sexual assault victims.

“One kit on the shelf is too many,” Masters told the Observer in August of 2022. “That’s somebody’s life hanging in the balance. That’s a rapist on the streets who is free and thinking they can violate someone else.”

Although Dallas may have sent its entire backlog off for testing over the past year, that’s not necessarily the case across North Texas. According to a spokesperson with the Fort Worth Police, the department has sent about 400 sexual assault kits to be tested in 2023, but still have approximately 200 that have not been tested. The Observer reached out to police departments in other large Texas cities, including Austin, with questions about the number of untested rape kits in their possession but did not receive responses after multiple requests.

In September, the Texas Department of Public Safety was awarded more than $3 million in grant funds to reduce a backlog of untested DNA and rape kits. According to a September report from the Texas DPS, “turnaround times for sexual assault kits (SAKs) remain under 90 calendar days for DPS labs across the state.” Additionally, the report notes, older SAKs that have never been processed continue to be handed over to labs for testing.

Speaking with the Observer now, more than a year after the last time she spoke to us about the number of untested sexual assault kits in Texas, Masters hasn’t wavered from the belief that she has championed for so long.

“I still say that one is too many,” Masters said in a recent interview. “I know we’ve come a long way, and I applaud that, I’m grateful for that, but still, I don’t see the excuse of having any kits on the shelf. I know you tell me it’s about training or funding, or outsourcing the testing to different labs, but having so many kits on the shelf just doesn’t rest well with me, it just doesn’t.”

State Rep. Victoria Neave Criado, a Democrat from Mesquite, authored HB 8. She understands where Masters is coming from and she, too, wants to see the remaining untested kits dealt with soon. But she’s willing to acknowledge that reducing the backlog more over the past year is a step in the right direction.

Lavinia Masters continues to push for police departments to test rape kits in a timely manner.

Mike Brooks

Neave Criado, who recently announced she is running for the District 16 state Senate seat against Democrat incumbent Nathan Johnson, said she is encouraged by what cities like Dallas have done so far. She also pointed to House Bill 1729, a 2017 law she spearheaded that enabled anyone applying for or renewing a Texas drivers license to donate $1 to go towards testing backlogged sexual assault kits when discussing the advancements in the cause.

“I just got data back that, thanks to the generosity of Texans, we have raised over $5.2 million,” Neave Criado said. She added that such crowdfunding measures should not have to do the heavy lifting for getting older kits tested, but that it’s a sign that the public sees this as a major concern.

“The Lavinia Masters Act really made Texas a leader in rape kit reform,” Neave Criado noted.

Masters, however, isn’t ready to hang a “Mission Accomplished” banner for the wrongs that have only started to finally be righted. For one, she’s not happy to hear that when faced with the backlog, Dallas Police sent the newest kits out for testing first, giving those a greater priority than the oldest ones. Hearing of Dallas’ approach brought back painful memories of the harrowing waiting game she was forced to endure.

“You have to find a balance,” she said. “You can’t say that we [sexual assault victims with older, backlogged rape kits] aren’t a priority. This time next year, you could have another thousand rape kits from victims that come forward, and what happens then? The new cases now will be the old cases then.”

Although Dallas police do not currently have any backlogged kits waiting to be sent out for testing, the department is still waiting on the results for hundreds of them. For their part, a DPD spokesperson told us “the testing of all kits is of the utmost importance and will be done to completion.”

There’s also the matter of how to keep the progress moving. The more distance that each passing year puts between the pandemic and the present is helpful in just about any walk of life. That seems especially true when it comes to rape kit testing, thanks to an increase in the staffing and funding that many agencies say wasn’t the case in 2020.

The state recently reauthorized the Debbie Smith Act, which aims to help police collect and test sexual assault kits in a timely manner, while also improving the capacity of state and local prosecutors to try such cases. But progress in 2023 aside, Masters wants to know about what the future might look like should the world find itself in yet another set of “unprecedented circumstances.”

“Nobody expected COVID to hit, but who’s to say COVID or something like it won’t hit us again?” Masters asked. “I went into a panic because COVID happened. I thought ‘what about all those victims of sexual violence?’ I knew kits were not going to get tested, but rapists aren’t afraid of COVID or any other sort of pandemic.”