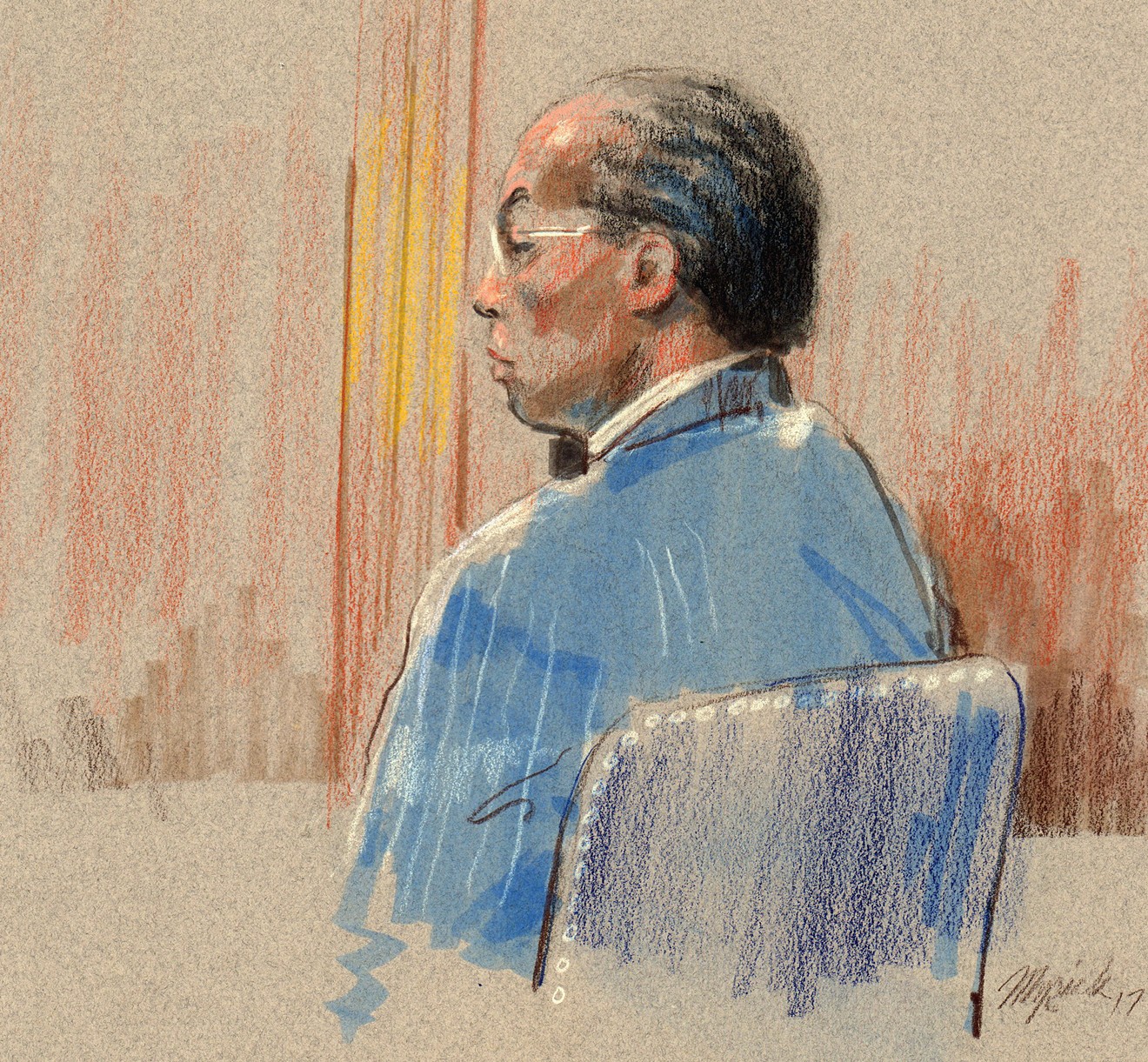

The ongoing Dallas County Courthouse federal corruption trial is taking place at two levels. Last week in the formal courtroom encounter, retired FBI agent Don Sherman and Dallas County Commissioner John Wiley Price never looked at each other, never moved an inch from their seats.

But at the second, subliminal level, the two ancient adversaries circled and menaced like shadow puppets, alone at last on the field of battle, glowering and taking each other’s measure.

Sherman, who has pursued public corruption in Dallas for a quarter century, is now humbled physically by injuries from a severe stroke in 2012. But on the stand last week he was sharp and wary as ever, fending off shots from young lawyers as if brushing away mosquitoes.

For anybody thinking of handicapping the outcome already in this trial, which is expected to go on for months, the first week showed Price and his team also have sharp arrows in their quiver. Even though federal investigators from multiple agencies have spent a decade piling up a fortress of financial evidence to prove Price and his assistant are crooks, lawyers for both defendants have already opened what seem like significant holes in the government’s case.

The government has amassed multiple terabytes of evidence to show that Price’s assistant, Dapheny Fain, and a political consultant, Kathy Nealy, who will be tried later, funneled almost a million dollars in cash, land and fancy cars as bribes paid to Price in a period of about a decade. For reference, Yahoo Answers tells me that one terabyte of data is equal to 86 million single-spaced Word document pages.

In the very long run-up to this trial — the investigation is 10 years old and it has been almost two years since the defendants entered not-guilty pleas — the sheer massiveness of the federal evidence has been taken by many as an indication of invincibility. Then again, as I watched the thing slowly unfold last week, it occurred to me that, if it really worked that way, the judge could just put both sides’ evidence boxes on a scale and award the victory to the side that weighed the most.

Here is the main question the Price/Fain lawyers opened: Price, Fain and Nealy traded checks and maybe cash back and forth like kisses at a teenage house party. And … well, we’ll wait for more on that aspect to emerge at trial. But the fact is, the checks went back and forth a lot. So did Price come out with more kisses?

When Sherman, the grizzled warrior, took the stand last week, he stated flat out that Price came out way ahead in those exchanges. He seemed to suggest that the back-and-forth part was pretty much a subterfuge to muddy the waters. That way, the two women could slip bribe money to Price that originally came from county contractors and other businesses with an interest in influencing outcomes at the county commissioners’ court.

In the Fain/Price transactions, Price’s lead lawyer, Shirley Baccus-Lobel, asked Sherman how he knew Price hadn’t simply been lending money to Fain’s advertising specialties business, called MMS, so the business could buy products to sell. The point there would go not only to the bribery accusation but to some of the tax charges against Price. Since loan repayments are not considered profit, Price would have committed no violation by not reporting those payments as income as the government has charged.

“We observed Mr. Price making injections of capital into MMS,” Sherman said.

“You saw money going from Mr. Price to MMS,” Baccus-Lobel corrected. “If that was immediately going to buy products, did you see those two things and connect them?”

“It would have been documented in that work product [his investigative notes] if we saw it.”

“Did you see it?”

“Without looking at that work product, I could not tell you with certainty.”

In fact, whenever Baccus-Lobel or her associate Christopher Knox pressed Sherman on exactly what he saw and did not see in the financial transactions between Fain and Price, Sherman answered with suave obfuscation — “If that is what the record shows, I would not deny it,” and so on.

I may have been imagining it, but I thought Sherman, who walks with a cane and has trouble seeing, caught a bit of a break on some cross-examination, especially where his memory was concerned. I couldn’t tell if he knew that and was playing it. And who am I to cast stones at old people?

But the gloves came off and the obfuscation was over when Fain’s lead lawyer, Tom Mills, took over the cross-examination. Maybe because he’s at least as old as Sherman, Mills, who is white-mustachioed and dignified, seemed to think he had a license to bring up the stroke thing. And he did.

“I wanted to ask you about your memory,” Mills said.

Two floors below the real courtroom where I sat in an annex with other reporters watching it all on closed-circuit TV, I thought I could feel a certain mild stirring among the senior members of the press corps, as if to say, “Oh, boy. Old guy fight.”

“Do you have access to a normal long-term memory in your opinion?” Mills pressed.

“I believe so, yes, sir. From what I understand, my long-term memory is intact.”

“Do you, in your opinion, have an intact short-term memory?”

“I think it would depend on what you’re referring to more specifically, sir.”

“Do you remember before lunch when we saw each other, you said you were glad to see me, ‘Bob?’”

“Yes, sir, Tom. Mr. Mills.”

Then Mills walked him through a series of test questions — when did he graduate from college, when did he enter the FBI, when did he retire? I was ready to give myself a pretty poor grade on some of the same questions and starting to feel sorry for Sherman, until I saw that Sherman was firing back at Mills with days, months and years for all of them.

And then, aha! I got it. Mills wanted the jury to see that Sherman, cane or not, shuffle or not, is sharp as ever and knows exactly what he does and does not remember. It was a point that became even more important the next day when an FBI forensic accountant, David Garcia, took the stand.

As soon as the direct examination of Garcia by his own side was over, Price’s lawyer, Baccus-Lobel, got him to admit that Sherman, his boss in the investigation, was already telling him years ago, before Garcia had even begun to analyze the Price/Fain/Nealy transactions, that Sherman intended to get Price indicted. Baccus-Lobel even got Garcia to admit that Sherman was putting the cart before the horse.

“What I am asking you,” Baccus-Lobel said, “is, [if you] form a conclusion before you have looked at what the facts are, that is not the proper order of things, is it?”

“That’s correct,” Garcia said.

Then the defense began firing its sharpest arrows. The cross-examination of Garcia was taken over by Mills’ associate Marlo Cadeddu, a former international banker and second vice president at JP Morgan Chase, before she graduated magna cum laude from Georgetown Law School.

Cadeddu, who thinks and talks so fast she has to slow herself down for the court reporter, walked Garcia through an entire series of transactions — many of them involving checks with “loan repayment” written in the memo lines. None of the ones she cited had been included in the FBI’s summaries.

She wrote each amount on an easel and then asked Garcia to add them up himself with either a calculator or his phone, I couldn’t see which. She came to various totals, but I thought Cadeddu got Garcia to admit to a total of more than $43,000 in omitted transactions. If I missed a beat, the amount may have been much more.

When she asked him if his summaries were not missing a lot of data, Garcia said, “Yes, but I would like to have a chance to double-check some of those numbers.”

“You are still missing a significant amount of money,” she said.

“Correct,” Garcia said.

“You agree with me based on the transactions, these numbers here [his own summaries] are missing some of the numbers.”

“I don’t want to really admit to that,” he said.

Two floors down in the annex room where I could not be heard by anyone in the real courtroom, I laughed out loud, because, no, I wouldn’t want to admit that, either. But, c’mon. The accusation that Price came out ahead only works if you count all of the money, not just the part that makes your case for you.

However long the rest of this trial takes will be plenty long enough for the defense to get the rest of the shadow play in front of the jury: Don Sherman bagged his first Dallas City Council man, Paul Fielding, and packed him off to prison in 1996.

Fielding was in cahoots with former Dallas City Council member, the late Al Lipscomb, whom Sherman took down four years later on 65 bribery counts. (Lipscomb’s conviction was overturned on appeal.) The Lipscomb investigation led Sherman to former Dallas City Council member Don Hill, whom he put away in 2009 for the rest of Hill’s adult life.

But all those guys were just bait in the real hunt, in Sherman’s long game, the stalking of John Wiley Price, who is either the biggest baddest crooked son of a bitch in Dallas history or the city’s greatest hero.

It’s very early. For all I know, the holes opened up last week by the defense will be bricked up solid by the government in the weeks ahead. But, look, if not, here’s the deal: If Sherman and his team spent all that time cherry-picking those numbers instead of honestly adding them up, then the terabytes may work against them with the jury, not for them. The time, the gritty determination, the sheer length of the hunt: That’s the real shadow play.

[

{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Inline Content - Mobile Display Size",

"component": "18855504",

"insertPoint": "2",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "2"

},{

"name": "Editor Picks",

"component": "17105533",

"insertPoint": "4",

"requiredCountToDisplay": "1"

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - MediumRectangle - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105532",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 8,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "7",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Inline Links",

"component": "18349797",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

},{

"name": "Air - Leaderboard Tower - Combo - Inline Content",

"component": "17105535",

"insertPoint": "8th",

"startingPoint": 12,

"requiredCountToDisplay": "11",

"maxInsertions": 25

}

]