Mike Brooks

Audio By Carbonatix

One of the funniest movies ever made remains unmistakable, uncomfortable and proudly not woke 50 years after it was unwanted and almost unreleased.

It was turned down by the likes of Johnny Carson, John Wayne and James Earl Jones. Multiple times during filming, Warner Bros. executives deemed the language and subject matter too cringy and pulled the plug. The name was frequently changed, from Tex-X to Black Bart to Purple Sage.

So what is it about Blazing Saddles, with its decidedly Dallas spice, that makes it simultaneously edgy and enduring? Consider the opening scene.

Before the intro music fully fades, Old West cowboy “Lyle,” played by Dallas native Burton Gilliam, refers to a collapsed Asian railroad worker with a racist slur and demands that a group of Black coworkers sing.

“C’mon boys, where’s your spirit?” Lyle says. “When you was slaves, you sang like birds.” He then drops the movie’s first N-word as he demands a “good ol’ … work song.” And so it begins. Both the squirming and the snickering.

Directed by actor/filmmaker Brooks and co-written by seminal Black comedian Richard Pryor, Blazing Saddles was nominated for three Academy Awards and earned a legacy as one of the most colorful movies ever produced because it never even attempted to tip-toe across the dangerous tightrope between smiles and sensitivity. Instead, it merely shrugged and said, “Aww to hell with it, let’s laugh.”

After the workers fulfill Lyle’s request by breaking into a soulful, jazzy version of Cole Porter’s “I Get a Kick Out of You,” the horseback posse returns the volley with a ridiculous, dancing, arm-flapping version of “Camptown Races.” The impromptu musical battle is interrupted by “Taggart” (Slim Pickens), who urges his white crew to get back to work while dropping another slur about gay people, particularly those from Kansas City. (Apparently, in Brooks’ version of the Old West, Kansas City was the San Francisco of its day.)

Offensive? Maybe if you focus on the word and not the point of the joke.

“It’s one of the funniest movies of all-time,” says Dallas’ Resource Center Advocacy and Communications Manager Rafael McDonnell, who for years has (unsuccessfully, so far) led the fight for the Texas Rangers to finally host a Pride Night at Globe Life Field. “I think folks understand how different things were back then and, of course, that changes how we view it today. What was acceptable then isn’t now. Blazing Saddles is so over the top. … God bless, Mel Brooks was always pushing the envelope.”

As the movie begins, so it goes. No marginalized group is spared as Blazing Saddles gallops ahead, firing arrows into every idiotic “ism” in its path, dropping 17 N-bombs, all but one from the mouths of white characters, along the way. Released Feb. 7, 1974, Blazing Saddles is problematic, full of racial stereotypes, sexist tropes and the most inappropriate of language. It’s also a buffet of belly laughs, with an 88% rating on Rotten Tomatoes and the No. 6 ranking on the American Film Institute’s “100 Years … 100 Laughs” list. It’s a gleefully vulgar spoof of Spaghetti Westerns, with a heaping dose of biting satire on racism.

Laughter is the enemy of fools, and the white characters letting the slurs fly are villains, fools or both. As co-star Gene Wilder’s character the Waco Kid puts it to Cleavon Little’s Black sheriff Bart after Bart gets smacked with a N-bomb from what appears to be a sweet old white woman: “You’ve got to remember that these are just simple farmers. These are people of the land. The common clay of the new West. You know … morons.”

When Harvey Korman, playing “Hedley Lamarr,” the evil henchman to Brooks’ dimwitted, horndog governor, makes a recruiting pitch to assemble a mob, he welcomes “rustlers, cutthroats, murderers, bounty hunters, desperadoes, mugs, pugs, thugs, nitwits, halfwits, vipers, snipers, con men, Indian agents, Mexican bandits, muggers, buggerers, bushwhackers, hornswogglers, horse thieves, bull dykes, train robbers, bank robbers, ass-kickers, shit-kickers and Methodists.”

It’s always dicey to apply contemporary standards to works produced in the past. Before we discard it atop the growing mountain of today’s banned books, consider that Blazing Saddles is from the time of Animal House and “Archie Bunker” and that it attempts to depict and satirize racism rather than endorse it.

Nonetheless, depending on your perspective, it’s either a “Good Ol’ Days” classic or “Cancel Culture” corrosive.

Lyle From Dallas

It also belongs with memorable Dallas-centric movies such as JFK and North Dallas Forty. “Lyle,” after all, grew up in East Dallas, attended Woodrow Wilson High School and fell into the role while working at Dallas Fire Station No. 39 on Shiloh Road.

“I never thought about being an actor until I was one,” Gilliam says. “I get a part in a movie that I still get recognized for around the world 50 years later. Pretty amazing.”

Gilliam was raised in fights, not film.

After graduating from high school in 1956, he boxed in the Golden Gloves and the Coast Guard. Following the family “business,” he became a fireman at age 21.

“Acting was something I never dreamed of,” says the 85-year-old Gilliam, wearing a Blazing Saddles cap during a recent lunch near his home in Allen. “My thing was getting in the ring and punching someone’s face.”

But in June 1972, while reading the newspaper at the fire station, he happened upon an advertisement to meet actor Ryan O’Neal and try out to be an extra for a movie. O’Neal was a movie star and also a boxer, somebody Gilliam always wanted to meet.

So he drove to the old Hilton Inn at Mockingbird and Central Expressway, across from Southern Methodist University, and almost left when he couldn’t find a parking spot.

“I came this close to turning around and going home,” he says with a laugh. “Now wouldn’t that have been something?”

O’Neal wasn’t there. Instead, after standing in a long line in a crowded ballroom, Gilliam met two young movie assistants: future director Gary Chason and a man who would become award-winning actor Randy Quaid. Upon introduction, the two became enamored with Gilliam’s Texas twang, the same one that years later landed him the job as the voice of Big Tex until officials at the State Fair of Texas decided it was too recognizably “Lyle.”

They hurriedly asked Gilliam to read a line: “Make him say ‘calf rope,’ Leeeeeee-roy!”

Giddy with their discovery, Chason and Quaid rushed Gilliam up to a suite. There, he encountered director Peter Bogdanovich, barefoot on a chaise lounge and being fed grapes by a woman who introduced herself: “Cybill Shepherd, nice to meet you.”

“Peter sat up and framed my face with his hands,” Gilliam recalls. “He asked me to read some lines off a script … like four scenes. That was it.”

Said Bogdanovich, “It’s as if it were written just for you.”

Gilliam was officially an actor, landing his first role as “Floyd” the desk clerk in Bogdanovich’s classic Paper Moon.

Three weeks later he received a call from Paramount Casting. The company flew him on Braniff Airlines to St. Joseph, Missouri, where he was paid $100 per diem and $255 in scale for a week’s work.

Gilliam, 34 at the time, hired an agent and began sporadic acting as a side hustle. But then came another phone call to the fire station.

“The guy just says his name and then goes quiet,” he says. “I didn’t know if there was an emergency or what. I’d never heard of Mel Brooks.”

Gilliam was flown first class to Hollywood four times during negotiations for a part in Brooks’ upcoming movie. When he initially balked, Brooks rewrote the script with an expanded role. When he again turned it down, Books had Pryor call to persuade him. When he finally received an offer to make $25,000 in one month for being “Lyle” in Blazing Saddles, Gilliam quit the fire station and moved to California.

He loved the script, despite his multiple slurs. It was a combustible time in America – less than 10 years after the Civil Rights Act and only six years after the 1968 assassination of Martin Luther King Jr. – but he didn’t falter at believing the movie’s comedy would drown out its controversy.

“I knew right away it was going to be funny, and that I could be funny,” Gilliam said. “The fact that word was in it so often didn’t really buzz on me. It was a different time, ya know?”

Dallas comedian Paulos Feerow makes a similar point.

“This was made in 1974. … In 1974 if I walked across the street someone would have called me the N-word,” he says.

But Feerow likes Blazing Saddles. He compares it somewhat to Quentin Tarantino’s 2012 Django Unchained, which, depending on whom you ask, has either 110 or 150 uses of the N-word. Feerow, who’s a fan, points out that the movie is set during the slave-era South. What word do we think white people – the bad ones – used then? Context matters.

As for Blazing Saddles, “the joke is not ‘that’s how Black people are.’… The joke is on these goofy white people.”

Of course, the joke works properly only if people get it. Some white people (see the Waco Kid quote above) see humor involving the use of racial slurs as a free pass to let them use the words themselves. Those people probably use them anyway in private, Feerow says.

Could a Blazing Saddles be made today? Feerow thinks it could, but it would be tricky, and not just because of the racially charged language. Tastes in comedy change. The way the jokes are presented would have to be restructured, and comedy is hard. That’s why Brooks is a genius.

But not all white comedians pushing the envelope on race are, Feerow says. He has seen white comedians with little experience delivering loaded jokes. It didn’t work.

“Maybe you’re not seasoned enough to tell that joke,” he says. (Feerow had a message to anyone ready to light him up online for being a comedy snob: Try getting on stage sometime.)

Cleavon Little and Gene Wilder in a scene from Blazing Saddles.

Warner Bros./Courtesy of Getty Images

The Last Round-Up

Initially, Brooks wanted Lyle to wear a mustache and emote a sinister vibe. Enter the trademark twang.

“I wasn’t going to play him like that,” Gilliam says. “I made Lyle a lovable goofball.”

For a six-week shoot in a California desert and a shoestring budget of $2.6 million, Blazing Saddles became a vintage flick that to this day has generations reacting, if not always laughing.

Today, critics on social media occasionally lambaste the movie’s frequent use of slurs, particularly the N-word. But maybe in their focus on particular words, they miss the point.

The View host Whoopi Goldberg made that point when she defended the movie in 2022. Blazing Saddles had come under fire on Twitter (now X) after Mindy Kaling, a star on the sitcom The Office, observed that her show wouldn’t fly in today’s era of heightened sensitivity.

“It deals with racism by coming at it right, straight, out front, making you think and laugh about it, because, listen, it’s not just racism, it’s all the isms, he hits all the isms,” Goldberg said of Blazing Saddles, according to Entertainment Weekly. “Blazing Saddles, because it’s a great comedy, would still go over today. There are a lot of comedies that are not good, OK? We’re just going to say that. That’s not one of them. Blazing Saddles is one of the greatest because it hits everybody.” The fans Gilliam comes across tend to agree.

“My favorite thing is when the grandmother and her grandson come up and ask to take a photo,” Gilliam said. “Before you know it, we’re all reciting lines and laughing.”

Blazing Saddles generated $26.7 million during its initial showing, and a total of $119 million in revenue including re-releases in 1976 and ’79. It won the 1975 Academy Award for Best Supporting Actress (Madeline Kahn), Best Song (“Blazing Saddles”) and Film Editing. It also received two thumbs up from Siskel & Ebert, which in the 1970s was worth a gazillion Yelp reviews in today’s currency. In 2006, the movie was deemed “culturally, historically, or aesthetically significant” by the Library of Congress, and was selected for preservation by the National Film Registry.

The world premiere 50 years ago took place at the Pickwick Drive-In Theater in Burbank, with co-stars Wilder and Cleavon Little watching on horseback.

In the movie’s zany climax (What’s the statute of limitations for a spoiler alert?), a pie fight at a modern-day Hollywood studio spills into the street, forcing Lamarr to take cover in an adjacent theater where he winds up watching the premiere of, you guessed it, Blazing Saddles.

After winning the confrontation with Lamarr and saving their town, Black sheriff “Bart” (Little) speaks to the people in the newly integrated town of Rock Ridge: “I’m going where I’m needed … wherever outlaws rule the West,” Bart says. “Where innocent women and children are afraid to walk the streets. Where a man cannot live in simple dignity. Wherever a people cry out for justice … ” “Bullshit!” the townsfolk yell.

“All right, you caught me,” Bart admits. “Speaking the plain truth: It’s getting pretty damn dull around here.”

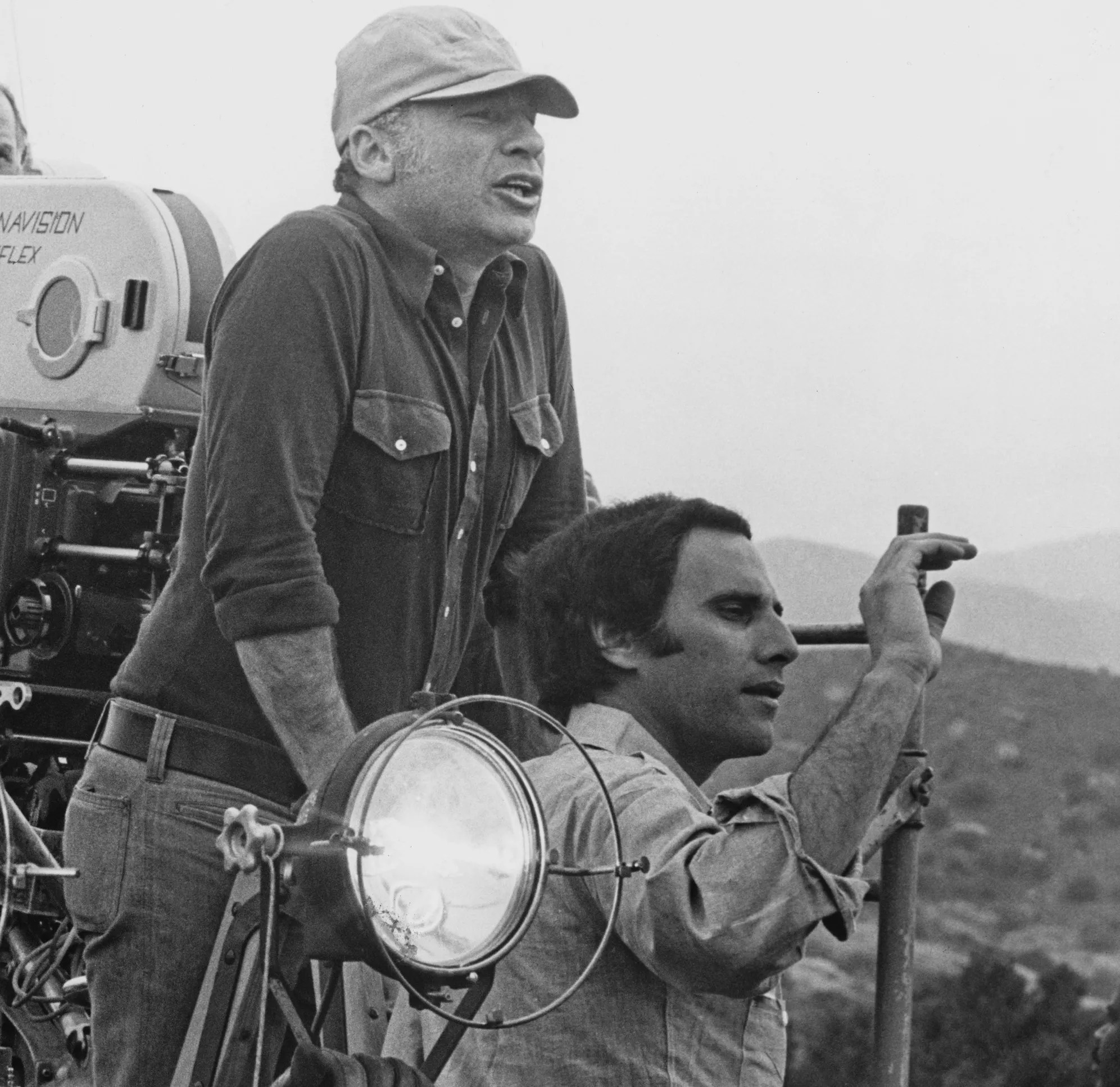

Director Mel Brooks (left) and producer Michael Hertzberg on Blazing Saddles’ set in 1974.

Warner Bros./Courtesy of Getty Images

And with that, he rides off into the sunset … in a limousine.

Almost everyone from the all-star cast is gone. Korman died in 2008; Wilder, 2016; Kahn, 1999. For decades, Brooks and Gilliam called each other after the death of one of their colleagues to reminisce about the actor and their movie.

There will be no more calls. Gilliam and the 97-year-old Brooks are the last two standing. “Between you and me,” Gilliam jokes, “I hope I’m the one that has nobody left to call, not Mel.” From the most humble and unlikely of beginnings, Gilliam parlayed his acting impulse into a career filled with more than 50 movies, 200 TV shows and countless commercials.

Though he gets recognized regularly, won a Reel Cowboys career achievement award in November in Los Angeles and even gets invited to appear as “Lyle” to chili cook-offs (with beans), he sees Blazing Saddles‘ journey as a sad sign of a society so busy being offended it’s forgotten how to laugh. How enduring and endearing is Blazing Saddles? Gilliam, who estimates he’s watched the movie 300 times, still receives royalty checks totaling $2,500 per year.

“We wouldn’t release the movie as is today, no way,” Gilliam says. “It’s been 50 years and we’ve evolved in the wrong direction. Stay on this same trajectory … in another 50 years we’ll all be afraid to talk to each other. A country of saints and mutes. No thanks.”