Marcus Spiske/Unsplash

Audio By Carbonatix

Last week, a small band performed outside a restaurant in a Dallas suburb. The live video of the event showed that none of the members were wearing masks, unlike the small group watching.

A woman, wearing a mask barely covering her nose, waved at the singer, even though they were standing a few feet apart. And then came the awkward body movements, the hesitation as they walked closer to each other in a moment that seemed to stretch out in slow motion. Had anyone else been watching with me, it would have made a great opportunity for a bet: Were they going to hug or not?

It’s the South, so of course they did. Politeness and warmth won out in the end.

As someone generally aware of germs, who’d sooner hug someone than shake their hand, I sympathized, though I still judged them. This isn’t 2019. Not hugging someone back no longer means “I don’t like you,” but the opposite: “I like you, and I’d like for you to live, so if I’ve unknowingly caught coronavirus, I don’t want to pass it on to you or someone close to you.” It’s a bit too high concept for the most mammalian, basic parts of our brains to learn, especially if your brain was made in Texas, where hugging is a standard greeting.

I was confident while watching that exchange that I knew what I would’ve done and what should be done in those cases. We should relearn that politeness now means keeping a respectful distance and not succumbing to peer pressure.

My daughter is severely immunocompromised, so for the past few months, no object (like packages or takeout) has entered my house without being disinfected first. To minimize exposure, only one of my household goes grocery shopping, which makes it a tediously long, methodical task, especially as we have to wipe down everything that might have been touched or breathed on by someone else before we put it away.

It’s like living inside a lab.

We go for walks, and nothing else, and other than when shopping for necessities, hadn’t come in contact with any human beings outside of our household except at a distance of over 10 feet.

Then, this past weekend, I received an invitation I couldn’t refuse. For the first time in months, I saw friends in a public space – a park – where we sat at a distance.

Because my concern with avoiding coronavirus seems to be more consistent than anyone else’s I know, I feel as though it’s almost usurped my entire identity, like we’re in a video game where the sole goal is to avoid getting infected. Except my daughter only has one life.

So I was surprised when my friend walked toward me when I first arrived at the park. “I can’t hug you,” I said. My friend didn’t say anything, and I wasn’t sure if she had even meant to hug me, but regardless I sensed disappointment and felt like a terrible human being who was shunning another.

The uncomfortable quality in that moment was subtle, unlike the one a few weeks prior when I was out for a walk and moved out of the way as a man came near me – and he cussed me out for doing so.

Maintaining a disciplined social distance is not making a statement about anyone else’s hygiene or lifestyle.

Other friends say they’ve felt bullied, mocked or scoffed at for taking precautions, with strangers giving them judgmental looks when they wear masks in public spaces.

“You’re one of those,” said a stranger’s expression, according to one friend.

While most countries are shaming those who violate lockdown orders, harassing those caught walking around the streets, in the U.S., the country with the highest number of coronavirus cases, we are being shamed for trying to avoid contagion.

Maintaining a disciplined social distance is not making a statement about anyone else’s hygiene or lifestyle, nor is it an analysis on their likelihood of carrying the coronavirus. I wouldn’t hug my own mother, and she’s in quarantine. The virus spreads with many never knowing they have it, and the only way to avoid it is by keeping away from everyone.

Even those who are social-distancing might occasionally touch public surfaces or catch the end of a cough in line at the store. Perhaps they live with others who interact with coworkers, who in turn touch door handles and shopping carts at stores and then touch their faces on the way home. Maybe they don’t disinfect food containers when they get delivery.

Observing these strict measures is not an act of paranoia – those are the proven paths of contagion. You don’t need to be particularly daring, negligent or ignorant to catch coronavirus, and since we can’t conduct a risk assessment of everyone we come in contact with, we simply avoid getting near you and touching those things you have touched.

My friends and I had agreed to meet at an open, isolated space, but strangers didn’t agree with our plans.

No one but me was wearing a mask, and keeping a distance did not seem to be a passing thought, let alone a priority.

It was a bright day made sweeter by the fact that the forecast had called for rain. Families walked together, and the illusion of normalcy was so vivid there was simply no room for a monster like COVID-19 to exist. Acknowledging the pandemic would’ve been like searching for killer zombies in a Renoir painting. Not one of those lovely families could possibly be a threat to my life, nor could my friends, could they?

Danger shouldn’t look so blissful. But it does.

There I was in a mask to protect everyone from my germs, even though the probability of my having coronavirus was extremely low. Wearing a mask, while a courtesy to others, in that context, makes you a Debbie Downer. The normal thing to do is take off your mask and participate fully in the illusion that we’re not in the midst of a pandemic – wearing it and denying others the relief of escapism seems inconsiderate, like pointing out that their luxury sheets are full of mites and their epic first kiss was an exchange of 80 million bacteria.

I sat as strangers walked by me more closely than they should have, and I ate cookies out of a store-bought box even though I’d forgotten to bring disinfectant wipes. I felt peer-pressured to forget the big picture, not by anyone in particular, but by the whole Renoir picture, by the afternoon, by the park. By the illusion of normalcy.

The idea that an invisible entity can ravage the lives we’ve built is something we may understand conceptually and something we can observe as death rates rise and businesses crumble. But it has not yet undone the schemata we’ve formed for facing the world and its elements.

Suggesting in any way, verbal or non-verbal, that a person might be infected with a deadly virus is just not polite.

Despite the hyper-awareness of the threats, we have a deep need to avoid offending others. Suggesting in any way, verbal or non-verbal, that a person might be infected with a deadly virus is just not polite, at least in normal times, and some take this perceived offense more personally than others.

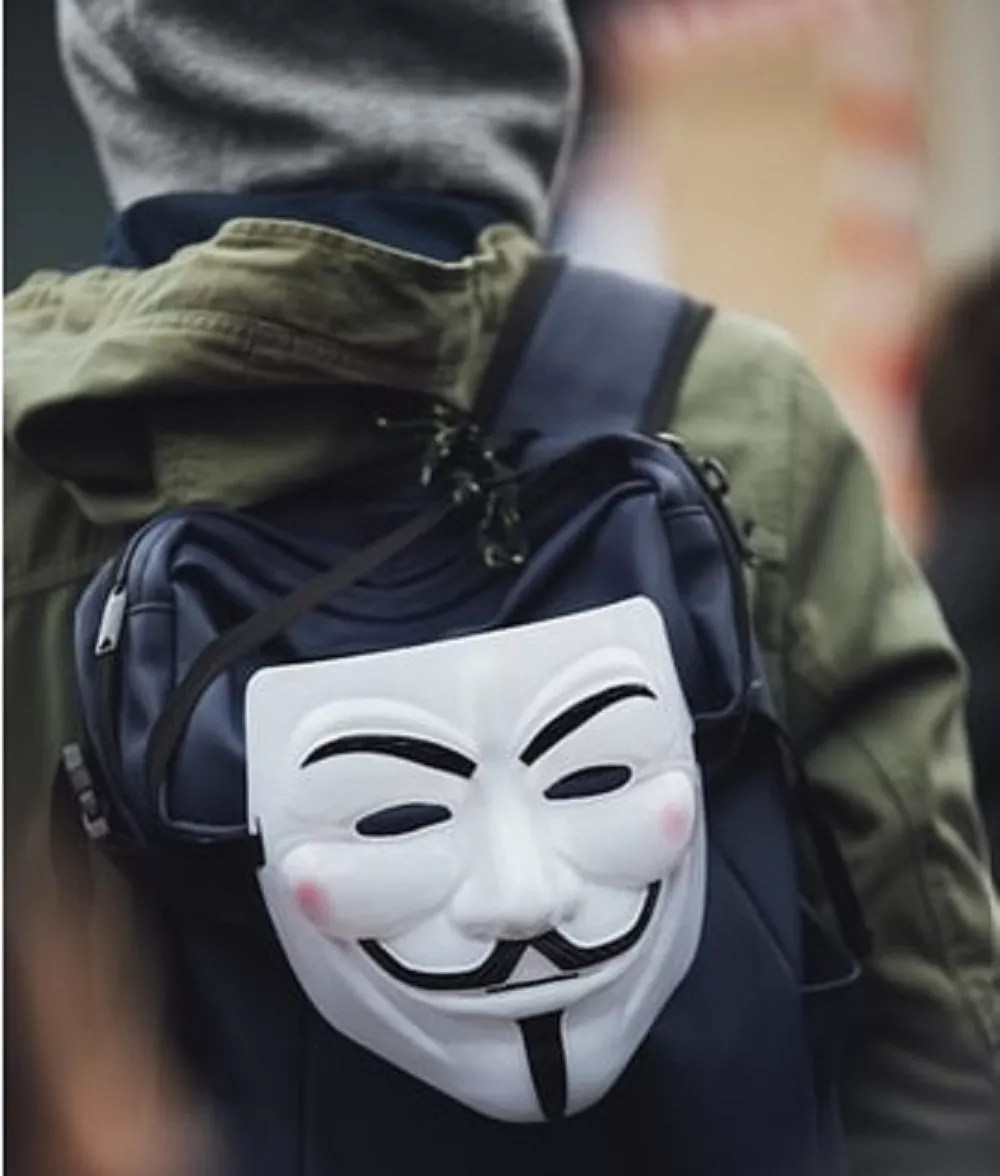

Wearing a mask has somehow turned into a political insignia, because in Trump’s America even disease is politicized.

As reopeners rally to end shutdowns, the tribalist chants escalated quickly from “I need a haircut” to “Bring all the guns” to “Fuck you, mask wearer.”

There are valid reasons to worry about shutdowns and their effects on the economy, but protesters need to come up with a better platform than “I need a haircut.” Advocating to reopen bars to people who will not maintain social distance (definitely not after a few drinks), and resuming other business as usual because you need a haircut is as shallow as someone advocating that businesses remain closed because they don’t want to start showering again before going to work. Replacing a thoughtful argument for the life-or-death consequences of a worldwide recession with a demand for a haircut is insulting in its petulant self-interest.

We find ourselves at a standoff between a colossal loss of livelihood and a health crisis.

The protests, however, show an embarrassing parade of white victimhood, paradoxically presented with the display of assault rifles and occasional swastikas as protesters proclaim their rights are violated by screaming in the faces of those concerned with reducing the 3,000 daily deaths projected for June.

In the world of corona denial, wearing a mask is interpreted as flashing of an enemy gang sign, the “proof” that the wearer drank the Kool-Aid.

Meeting a non-masked person as you wear one yourself puts you at a moral standstill of mutual resentment. Masks are uncomfortable and they make talking harder. Yet you’re wearing it for your cohorts’ and for strangers’ benefit while they’re not showing you the same courtesy. Even if reopeners believe coronavirus to be a hoax, screaming in the faces of those masked to protect their neighbors is double the insult.

Making the call for nonessential businesses to open back to 25 percent capacity is a ploy similar to a child’s asking to stay up 10 more minutes. They know no one is watching the clock. Those 10 minutes stretch as parents fall asleep first.

The 25 percent capacity is a number that no one will enforce, because if people like me, a mother who would go to any lengths to protect my child from death, get so intoxicated on the high of social contact that I can barely stay 6 feet away from an unmasked friend, then it’s extremely unlikely that bar patrons will adhere to strict guidelines.