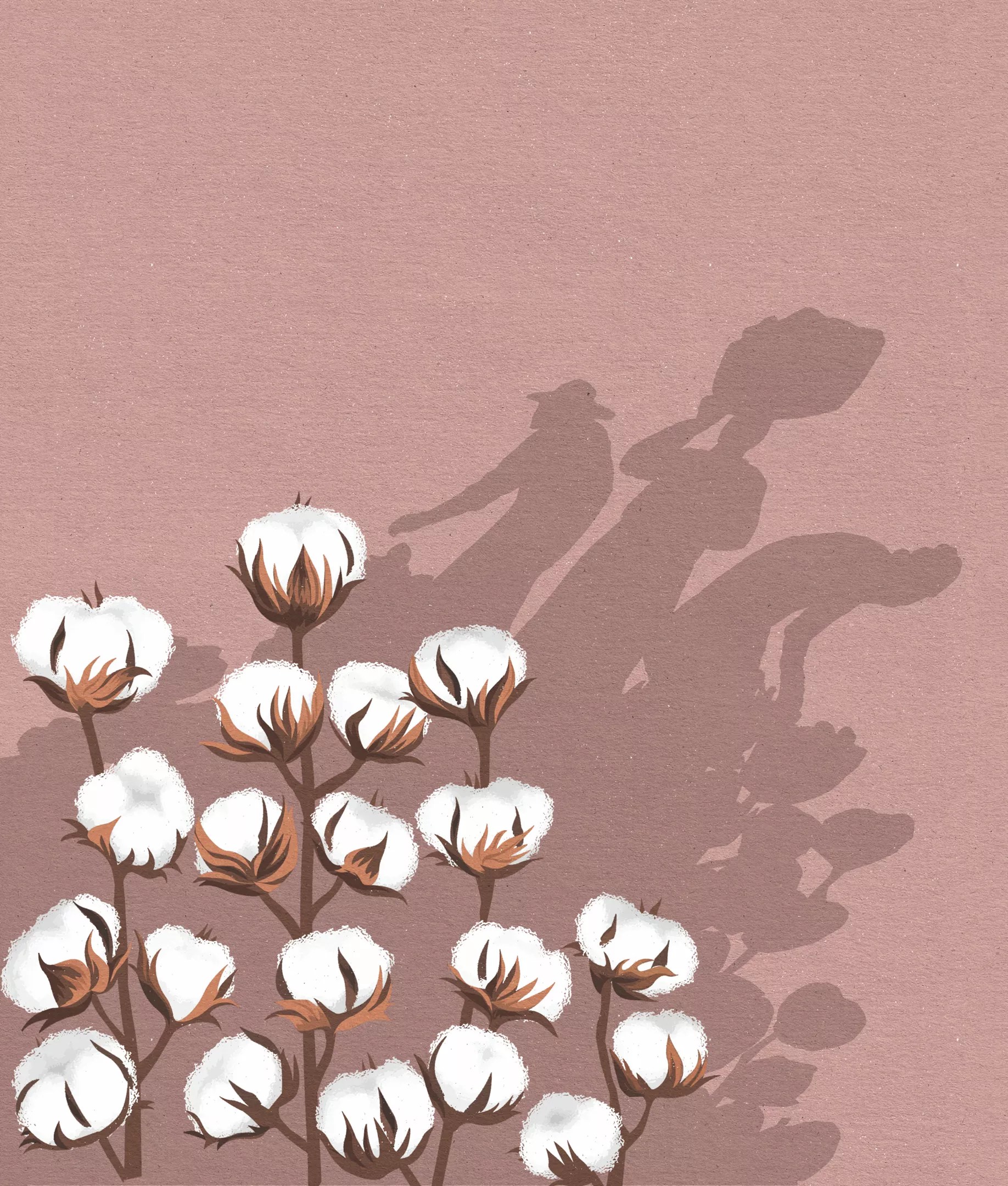

John Holcroft

Audio By Carbonatix

Out on a rural piece of land in Lancaster, Clarence Glover stepped up to a structure that sat on a wooden pallet and was wrapped in a blue tarp. Storm clouds overhead spat out a light drizzle as Glover untangled knotted up bits of bungee cable that held the tarp down. When he was done, Glover revealed what was underneath – a 500 pound bale of white gold, otherwise known as cotton.

He could tell you all about the stuff, like who picked it, where it was processed, and all the possible uses for it. One figure he cites often is 313,600: that’s how many $100 bills one 500-pound bale of cotton can produce.

The white gold built the city of Dallas, Glover said, a fact that he thinks has largely been forgotten. Shedding light on this history and its implications for the city today has become somewhat of a crusade for Glover, a 66-year-old civil rights activist and former history professor. Understanding cotton’s role in our history, Glover said, is crucial to reckoning with the city’s racist past. Without this understanding, he argues that racial and economic justice is unattainable.

“When you’re talking about racial justice, you have to understand it begins with economic justice because of what African-Americans contributed to this city and to this nation and to the world, being the epicenter of the cotton industry in Dallas at the time,” Glover said.

He said Black people didn’t see the fruits of their labor in the cotton industry during slavery. Then throughout the Jim Crow era, they were never compensated fairly for picking cotton while white people profited disproportionately off it. “So, now we have to have a conversation on how do we begin to distribute wealth more equitably,” he said.

Reparations could be the answer, Glover said. Looking at the history of the cotton trade throughout slavery and the Jim Crow era, who picked the stuff and how they should be compensated for that work, could be used to determine who gets how much.

“That’s going to be a difficult conversation, but cotton becomes a concrete object around which we have this conversation now,” he said.

It’s a difficult conversation to have, Glover said, because it’s painful and shameful. It’s shameful for white people to recall because of the part their ancestors played in creating it, and it’s painful for Black people because of the horrors they endured and the inequities in the cotton industry throughout slavery and the Jim Crow era.

One of his messages for years has been that Black people should be proud of their part in the cotton trade because of the instrumental role it played in the global economy at the time. They should also be retroactively compensated for the role they played in the economy. It’s not a very popular opinion, he said, but it’s one he’s held for decades.

Clarence Glover holds cotton in front of his Elm Thicket-Northpark home.

Jacob Vaughn

Glover moved to Dallas from his hometown of Shreveport over 40 years ago. Raised in the historic plantation town Dixie, Louisiana, he picked cotton as a child and heard stories from relatives about doing the same. This filled him with a sense of pride about his family’s history and role in the cotton trade. It’s this sense of pride that led him to create African American Cotton Pickers Day in 2020. Designed to honor African Americans’ role in the cotton trade, it’s observed on the fourth Monday of October during the height of the cotton-picking season in Texas.

In October 2022, Glover hosted an event in Elm Thicket-Northpark, just east of Love Field, for African American Cotton Pickers Day in collaboration with the city of Dallas. About a dozen people turned out to a small room at the K.B. Polk Recreation Center to learn from Glover and discuss the historical significance of the cotton trade in the city.

Glover passed out copies of Jim Schutze’s book The Accommodation and asked everyone to turn to Chapter 3. He read the opening paragraphs, which detail the first in a series of bombings of Black homes in South Dallas. One of the homes was owned by a man named Horace Bonner.

As the book explains, the white working class and middle class didn’t like the idea of people like Bonner having enough money to buy houses in their neighborhood. According to the book, this intolerance led to the bombings.

“When you’re talking about racial justice, you have to understand it begins with economic justice because of what African-Americans contributed to this city…” – Clarence Glover

The Bonner name is an important one in the history of Dallas’ cotton trade, Glover said. Anderson Bonner, Horace’s grandfather, was an enslaved African man who worked the plantations. After he was emancipated he was able to acquire 25 acres of land in Dallas, and his farm eventually grew to 2,000 acres, some of which was used to grow cotton.

Glover suggested that Horace Bonner had the means to buy the house that was bombed at least in part because of the money his family had generated from cotton.

Glover then introduced the small audience to Walter Bonner, Anderson Bonner’s great grandson. Walter Bonner, 78, said when his great grandfather was freed from slavery, he had many skills he used to make money and buy land.

Eventually, people from all over North Texas were picking Anderson Bonner’s cotton, Walter Bonner said. “They’d take it to the gin and make money.

He said: “Believe me, cotton built this city. If there hadn’t been cotton, there wouldn’t be a Dallas.”

This is the message Glover has been trying to get out for years. To illustrate this, he took us around one day to see remnants of the cotton trade scattered throughout North Texas. One of the first places Glover wanted to go to was the home of William Cochran, the man often credited for bringing cotton and wheat farming to what later became Dallas.

We met at Glover’s house in the Elm Thicket-Northpark neighborhood in early December. Glover was wearing a traditional sack used for storing cotton as it was picked in the fields. Inside the faded white sack were clumps of hand picked cotton. His neighborhood is part of Dallas’ cotton story too, he said.

In the 1860s, emancipated African Americans in Texas began moving throughout the state. Some of these freed men and women created their own communities in and around Dallas. These freedman towns included Joppa, Tenth Street, and Elm Thicket-NorthPark. Many of those men and women likely worked on cotton plantations when they were enslaved and would continue to do so in the following years as sharecroppers.

Elm Thicket-NorthPark was a mostly Black neighborhood when Glover moved in over four decades ago. More white people have moved there in recent years, some into new houses that tower over the small single-family homes like Glover’s that used to make up most of the neighborhood. Some of Glover’s white neighbors walked past his house as he demonstrated how slave owners would whip their slaves. Wielding a leather whip, Glover waved his arm in front of him and flicked his wrist. The whip shot out several feet in front of him and made a menacing crack that echoed throughout the neighborhood. As a neighbor passed by walking a dog, Glover smiled and waved before we headed to the home of William Cochran.

The Peters Colony was formed in 1841, bringing people like William Cochran to North Texas. Stephen F. Austin, the “father of Texas,” led people like Cochran to colonize the area. Around the time his family got the Texas land, Austin noted the importance of the cotton trade and how it would only be profitable through slavery. According to the Texas State Historical Association, Austin wrote in 1824, “The principal product that will elevate us from poverty is cotton and we cannot do this without the help of slaves.”

Cochran moved his family to North Texas after seeing a sample of soil from the area. The family was given a land certificate in the Peters Colony in March 1843. The city of Dallas had just been established two years earlier and Dallas County would be established in 1886. Cochran was elected as the first Dallas County clerk. He later became the first to represent Dallas County in the state legislature. He established a farm where he grew wheat and cotton, as well as fruits and vegetables. The family would later build a corn and cotton mill on their land.

The Cochrans also had a cotton plantation on land that became Dallas Love Field. Glover said the cotton picked at this plantation would be processed in the Cochran family’s gin. The U.S. Army purchased 670 acres of this land and turned it into a flight training base to prepare pilots for World War I. The Army stopped using the facility in 1919 and the land was then leased back to the city and turned into Love Field. The family’s home still stands today and is a Texas Historical Landmark.

“Believe me, cotton built this city. If there hadn’t been cotton, there wouldn’t be a Dallas.” – Walter Bonner

The next stop was Anderson Bonner Park.

Anderson Bonner and his family were some of the few Black people who were able to benefit from this booming industry at the time. Dallas dedicated a park west of Medical City Hospital to Anderson Bonner, naming it after him in 1976. Last year, a sculpture was placed in the park to honor him.

The sculpture is called “Sankofa” and it was created by an artist named Andrew Scott. On his website, Scott explains that Sankofa is a word in the Twi language of Ghana that means “go back and fetch it.”

Glover interprets like this: “You must know where you come from to know where you’re going.”

The sculpture depicts a bird holding down an egg on its back with its beak. In the center of the bird’s body is a sculpted portrait of Anderson Bonner with a brief biography on the other side. It’s written in first person, explaining how Anderson Bonner and his brother were listed on an inventory of property by their slaveholder Willis Bonner. They were living in Alabama at the time. When Willis Bonner died, his wife moved to Dallas, bringing with her Anderson Bonner and his brother Lewis Bonner. The two were emancipated in 1865. A few years later, they registered to vote in Dallas County’s Precinct 5.

Clarence Glover explains the meaning behind Sankofa sculpture at Anderson Bonner park. It was created by the artist Andrew Scott and depicts Anderson Bonner.

Jacob Vaughn

The biography on the sculpture doesn’t note that Anderson amassed 2,000 acres, an omission that Glover said diminishes his accomplishments.

Now, Medical City Hospital sits on some of the land he owned and Central Expressway cuts right throughout. Glover said he’s advocated for a cultural center to be built along Central Expressway in honor of Anderson Bonner. “Central runs through his land,” Glover said. “I’ve told the family, I’ve told the city, we should have the Anderson Bonner Center on the expressway, a cultural center with his history and life.”

We drove through Deep Ellum to our next stop, the Continental Gin Building.

Before U.S. inventor Eli Whitney patented the cotton gin, Glover said enslaved African people handpicked the cotton and separated it from its seeds. “It took all day. It was laborious,” Glover said. “Once the cotton gin was invented, it made it far easier to separate the seeds, so you didn’t need people doing that job any more. So, you put those people over there picking more cotton while the gin separated the seeds.”

This increased the volume of cotton picked and processed.

When a man named Robert S. Munger moved to Dallas around 1885, he brought with him something he’d been calling his improved cotton gin. Three years later, he started the Munger Improved Cotton Machine Co. “That revolutionized the gin making process, the machines that separate the cotton,” Glover said. “The railroads would come in there, take those gins out” and ship the machines elsewhere.

Munger built a cotton gin factory on Elm Street that is now known as the Continental Gin Building. Just down Elm Street was the Southern Rock Island Plow Co. building where the plows needed to grow the cotton were manufactured. The building was later turned into the Texas School Book Depository, which is now the home of the Sixth Floor Museum

“On one end you had the plow company, on the other end you had the gin company,” Glover said. “Elm Street became an industrial cotton mecca for America.” The Dallas Cotton Exchange was downtown. It was the largest inland cotton exchange in the country and made Dallas a hub for the booming cotton industry.

Author Sven Beckert argues in his book Empire of Cotton: A Global History that all of this action in the cotton industry helped shape global capitalism during the Industrial Revolution, more so than steam or steel.

This industry allowed white people to accumulate generational wealth while Black people were stuck in a loop of generational labor from which they’d never see the full benefit, Glover said.

“All this was cotton at one time. When I look at these fields, I see people.” – Clarence Glover

After hours of driving around Dallas, explaining to a young, white reporter the extent to which cotton is interwoven cotton is in the city’s history and the plight of the people who picked it, Glover walked into the Continental Gin Building. What was once the largest manufacturer of cotton gins in the world is now a retail and office space with a small coffee shop. Still wearing a traditional cotton sack, Glover walked up to the register at the coffee shop to order a hot chocolate and a cookie. He saw a piece of merchandise the shop was selling that said, “Don’t be a cotton-headed ninny muggins.” He was a little offended, but he laughed it off and asked the barista what it was supposed to mean. She laughed nervously, saying she didn’t know and that she only worked there.

It seemed to be a reference to a scene in the movie Elf in which Will Farrell refers to himself in a disparaging way as “cotton-headed ninny muggins” because he can’t build toys as fast as the rest of Santa’s elves.

The website for the Continental Gin Building includes the history of the place. The site explains that it housed Robert Munger’s company until 1900 when it was bought by Alabama’s Continental Gin Co. The history is there, and cotton is used in some of the branding for the building now, but it all feels a little whitewashed to Glover.

Clarence Glover stands next to a 500-pound bale of cotton.

Jacob Vaughn

He tried not to let it bother him as we headed to our final stop in Lancaster. A friend of his owns land in the city and lets Glover keep his 500-pound bale of cotton there. On the way, Glover points out large swaths of land that were once dedicated to cotton.

“All this was cotton at one time,” he said. “When I look at these fields, I see people.”

On his friend’s land, Glover grows mustard greens and collard greens and keeps up with his bale of cotton. He said it likely would’ve taken just a day and a half to pick all of the 500 pounds. Imagine how things might have been different had the people who picked it been fairly compensated, Glover said.

“If we were properly compensated, my gosh, what would have happened?” he said. “What would America look like? Where would we be today?”