"If you want to think of human origins as a straight line, then there has to be a missing link, but what we're finding is a braided stream with several species existing at the same time," says Dr. Becca Peixotto, the director of the Perot Museum of Nature and Science's Center of Exploration of the Human Journey. "It's branching off and joining back in and eventually through 6 or 7 million years, it comes to where we are now on the planet."

Two recently discovered sets of remains — including a 2-million-year-old skeleton called Australopithecus sediba, aka "Karabo," and a 200,000-300,000-year-old specimen called Homo naledi, aka "Neo," from excavations from South Africa — have added another branch to the complex, twisted tree of human evolution and development. Both of these delicate specimens are on display at the Perot Museum for their first public appearance in the country as part of a limited exhibit called Origins: Fossils from the Cradle of Humankind. The limited exhibit is open and runs until March 22.

"This is one that all others will be compared to for that species, and that's something that just doesn't happen very often if ever," says professor Lee Berger, the renowned author and paleoanthropologist from the University of Witwatersrand (Wits University) in Johannesburg, South Africa and National Geographic explorer-at-large who oversaw the excavations.

Peixotto and Berger discovered Neo and Karabo, respectively. Berger's then 9-year-old son Matthew discovered Karabo's remains at an excavation site in Malapa, South Africa. Five years later, Peixotto unearthed Neo after a pair of cave hunters first came across the remains in the Rising Star cave system at the Cradle of Humankind World Heritage Site, located northwest of Johannesburg."The significance of this exhibition is really to investigate our shared human journey and understand what we really still have to learn about our human origins and where we came from." — Dr. Linda Silver

tweet this

Some of the entrances to the Rising Star caves are as narrow as 7 inches wide. Teams had to put out a call on social media for slender volunteers to enter the cave as "underground astronauts," Berger says.

Getting these stunning, groundbreaking remains to the museum required a great deal of planning and care. The remains are not only physically delicate but they are also under strict heritage protection laws. Berger approached the university in 2018 about bringing the remains to the Dallas museum after meeting a major museum donor, says Zeblon Vilakazi, the deputy vice-chancellor for research at Wits University.

"Initially, I thought it can't be done," Vilakazi says. "These are protected by national and global heritage laws, which mean to move them is a high risk project. Lo and behold, professor Berger had the confidence and he had spoken to people and he had done his homework."

It took over a year of transportation and legal planning to get the remains from Africa to America, and when it came time to do the physical transport, extra steps had to be taken to ensure their safety, including official documentation and even armed guards.

"We traveled with diplomatic letters from the people of South Africa through Dubai and here to Dallas," Berger says. "They were escorted with armed police escorts at every point. We were met in Dubai by the same and met here by the wonderful TSA agents and officials at the DFW Airport who helped us bring these precious and fragile objects seamlessly. It's a great welcome for some of these individuals who are 2 million years old."

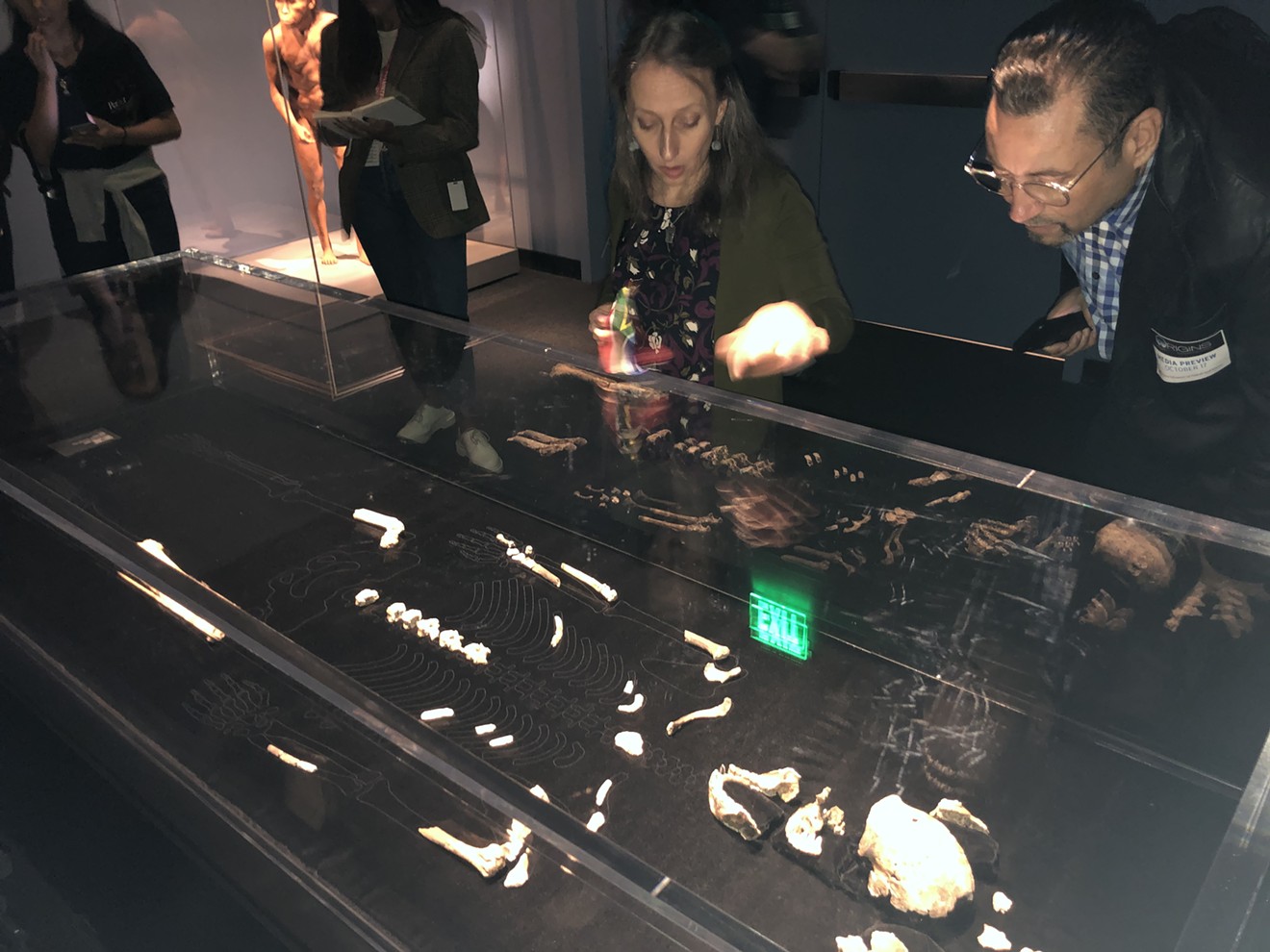

The Perot Museum's exhibit shows more than just these new species of humanity's ancestors. The exhibit also explains the methods and challenges of finding and excavating the remains, significance of these findings, and the contributions made to the further understating of human development and evolution. Guests can even see a team of researchers examine, test and study the remains as part of a research project underway at the museum.

"The significance of this exhibition is really to investigate our shared human journey and understand what we really still have to learn about our human origins and where we came from," says Dr. Linda Silver, the Perot Museum's Eugene McDermott chief executive officer.

A researcher studies newly discovered remains of human ancestors as part of a new exhibit at the Perot Museum.

Danny Gallagher

Vilakazi says these newly discovered remains can unlock answers to the development of humankind, about the biology to its behavior. For instance, Berger notes that the discovery of Neo came about from a dig site where 25 individuals' remains have been found, leading to the possibility that these separate human species "deliberately disposed of their dead."

"The entire story of human evolution is a scientific story," Vilakazi says. "So what the scientists here led by professor Berger in Johannesburg do are try to pick up some of the missing clues of what makes us as human beings. They dig up old fossils to try and put together all the evidence of the history of human evolution that's taken place. It's very important for us to understand human nature itself. You cannot know your current self if you don't know your past."

Berger also believes these discoveries should be examined and studied by everyone, regardless of their scientific credentials. He says it's important that the public get the opportunity to see these and other significant scientific discoveries for themselves.

"I am a firm believer that science should be done in front of people," Berger says. "For too long, scientists have done science in black boxes and ivory towers and we have lost touch often with many of the public who we are just telling the results out instead of sharing the entire process. That's why these fossils have been shared with the world from their discovery through the analysis of them like we're doing here and then putting them on display.

"How can we understand that we are part of this natural world and have a deep connection to it and a deep connection to each other without sharing it?"