In 2017, the National Football League generated revenue of $14 billion.

When a man sporting five zeroes butts heads with a corporation flexing nine, it’s no surprise who leaves with the migraine.

“It’s really a shame,” Johnsen says between sips of coffee at Company Café on Lower Greenville. “Because I think football needs me more than I need football.”

While America’s most popular sport languishes in a slump partially spurred by its concussion crisis, Johnsen, who believes he has an answer to curtailing the problem, is moving on to his next project. Convinced the NFL has no interest in him or his DNA methodology as part of any health-and-safety solution, Johnsen is redirecting his expertise out of players’ helmets and into DFW’s health-conscious bodies.

Goodbye, Simplified Genetics. Hello, FitLab.

“Look, I approached the NFL with a key to its lock,” Johnsen says. “I told them I could make football safer. I could save lives. I didn’t want a penny, only an endorsement. But they didn’t want to hear it. Wanted no part of it.”

Players taking a knee in protest during the national anthem posed a short-term public relations hiccup for the NFL, but the concussion calamity could prove terminal. Johnsen says he presented the league with a research-backed plan that in 10 years would’ve eradicated new concussion-related brain problems in its sport. By 2040, Johnsen says, no one playing in the NFL would have suffered a single concussion he wasn’t genetically prepared to fully recover from.

Whether that's a groundbreaking, game-changing promise or merely science stretched to fit a business plan, Johnsen says the NFL didn’t take him seriously enough to make a rational determination.

“I don’t have tangible proof that the NFL intentionally shut down my company,” he says. “But let’s not kid ourselves; the NFL intentionally shut down my company.”

While the NFL struggles with protecting its players from violent head-to-head collisions and its former players from the debilitating, often fatal effects of concussion-related brain disease (specifically chronic traumatic encephalopathy), Johnsen now pours his energy and money into FitLab. Boasting itself as America’s first franchise of genetically based group fitness facilities, FitLab will be backed by DNA engineering in the form of “Fitscripts,” which will assign members the optimal exercise, nutrition and supplements geared to their genotypes. FitLab’s flagship location is scheduled to open May 1 in Mockingbird Central Plaza.

But as excited as Johnsen is about his next reincarnation, he may never fully flush the frustration over what might have been with the NFL.

“Honestly,” he says, “I think I scared them shitless.”

From Kung-fu to science

Johnsen, 53, navigated a circuitous path to the doorstep of one of the biggest medical mysteries in the history of sports.His biological mom left before he knew her. His stepmother died of a heart attack in his arms during a convention at Dallas’ World Trade Center. He became a rebellious, adventurous mess of a teen. Drugs here. Suspensions there. An educational road that weaved from Richardson to Jesuit College Preparatory School to military school in Virginia. His studies at Sherman’s Austin College lasted all of six weeks.

Along the way, Johnsen developed a hard bark and a quirky perspective. He dedicated himself to growing up to be either James Bond or the president of a television network.

“If I could control what people watched on TV, I’d be a powerful guy,” he says. “And 007, he’s just fucking cool.”

Johnsen’s grand plan was hijacked by, of all things, kung fu. Fascinated by the ability to both defend himself physically and arm himself psychologically, he plunged into martial arts and eventually ascended to become a Tibetan kung fu master, with expertise in lama yoga, tai chi, chi gong, acupuncture, herbology, jiu-jitsu and meditation in the form of — or so he says — lucid dreaming and out-of-body travel.

Impressive at cocktail parties. Inadequate to pay the bills.

Johnsen reluctantly followed his father’s footsteps into the corporate lighting industry and developed into a successful salesman. He ran offices in Dallas and Huntington Beach, California, and set up shows across the U.S."I think football needs me more than I need football.” – Kurt Johnsen

tweet this

It was lucrative, but after a certain day in 2001, it felt ludicrous. Already scarred by having to make his stepmother’s call to 911, Johnsen was suddenly transformed by 9/11.

“It was like, ‘Wait a minute, what am I doing with my life?’” he says. “I called my sister and told her, ‘We have to do something. Something we love. Something that actually matters. Life is too short for this shit, and we both know it.’”

Days later, the two bicycled around White Rock Lake and promptly quit their jobs — Johnsen as a lighting exec and Jennifer as a chartered financial analyst with KPMG.

“Let’s help animals!” his sister exclaimed.

“Yes,” replied big brother, “if by animals you mean human beings.”

With that, Johnsen committed to stop lighting conventions in favor of illuminating unconventional wisdom. He would demystify and mainstream yoga. Long before he founded his genetics company, he launched American Power Yoga.

“This is my math,” he says. “Kung fu + yoga + Bruce Lee + [self-help guru] Tim Ferriss + personal tragedy + abrupt career changes + full sequence genetic analysis. That’s just who I turned out to be.”

The transition worked. So much so that at one point, even the NFL — via the Dallas Cowboys — embraced him.

As American Power Yoga, a fusion of martial arts into traditional practices, gained traction around 2008, Johnsen grew busy teaching classes, training instructors, cutting ribbons on new studios and engaging in partnerships across the country. He had yoga #trending before hashtags were a thing. One of the businesses that took notice was the Cowboys.

First approached by Kelli Finglass, longtime director of the Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders, Johnsen commenced a business partnership with Charlotte Jones Anderson, the Cowboys’ executive vice president and chief brand officer (and daughter of the team’s billionaire owner, Jerry Jones). Before he could say “downward dog,” American Power Yoga was offered the opportunity to partner with America’s Team. Johnsen instructed the cheerleaders in regular classes and put them on video. The result? Fitness Magazine named Dallas Cowboys Cheerleaders Body Slimming Yoga its best yoga DVD of 2010.

“I was the official yoga instructor for the world’s most popular dance team,” Johnsen says. “We sold out of the video. It was a pinch-me time in my life.”

But as he would later be reminded with all the subtlety of a sledgehammer to the shins, business is business.

While his programs and video were enjoying national success, Johnsen found himself perplexed by gnawing questions posed by students: “What should I do? What should I eat? What should I take?” They wanted to know what type of exercise, diet and supplements would most benefit them.

So in 2010, Johnsen launched APY60, an intense, 60-day program designed to reshape minds and bodies through a sternly scripted plan. It worked for most, but, confoundingly, not all. Uniform programs aren’t designed to produce random results.

“I’d say 75 percent lost weight, toned up, felt better,” Johnsen says. “But some actually gained weight and felt worse. My mind was completely blown. How could people diligently following the exact same exercise and nutritional routines get drastically different results?”

For the answer, Johnsen sought out his father-in-law, molecular biologist Bill Fioretti. He was president and investor in TransGenRx, a now-defunct drug manufacturing facility on the campus of Louisiana State University in Baton Rouge. Unlike Johnsen, Fioretti had a background in science. His deduction was uncomplicated.

“Stimuli is the same,” Fioretti told Johnsen. “It’s the receptors that are different.”

The answer was genetics.

DNA coding provided each APY60 client with information about receptors that would interpret the introduction of identical stimuli — food, exercise, etc. — independently and uniquely.

It was a light-bulb moment that lit a company, Simplified Genetics.

The business headquartered in Mockingbird Station launched with a mission to create, through a blend of genetics, exercise physiology and nutritional understanding, an algorithm that would allow DNA data to be translated and broken down into bite-sized, customized programs for individuals to achieve optimal results. For three years, Simplified Genetics pored over research and tested more than 11,000 customers.

But something peculiar happened on the way to scripting healthier, happy humans: Simplified Genetics stumbled onto a product that Johnsen believes could essentially predict the severity of concussions and, in turn, help save the NFL.

“I’m not a scientist or a board-certified physician,” Johnsen admits. “But you’d have to be blind to not recognize the importance of what we created. We were crusading on how to improve yoga, but we unearthed the cure for the concussion.”

A cure? Not exactly. But a tool that could help predict who should avoid getting repeatedly conked in the noggin? Maybe.

Genes linked to head trauma

In their continuing attempt to wrap their heads around the concussion conundrum, NFL owners approved a new rule last month that will penalize any player for lowering his head to initiate contact. In essence, it will now be a 15-yard penalty for using a helmet as a weapon instead of a shield.The league has wrestled with this since 1994, when then-Commissioner Paul Tagliabue formed something called the Mild Traumatic Brain Injury Committee in response to players’ growing concerns about head injuries. The league initially downplayed the problem, even once claiming its players had “toughened up” and “evolved” beyond the dangers of concussions. By 2010, pressured by a flood of damning evidence, the NFL donated $30 million to brain research. A year later, however, 4,500 former players filed a class-action lawsuit claiming the league had withheld knowledge about the severity of concussions. In 2013, the NFL settled the case for $765 million but adamantly refused to admit any wrongdoing or mishandling of information.

The high-profile deaths of former stars such as Frank Gifford, Mike Webster, Junior Seau, Ken Stabler, Andre Waters, Dave Duerson and Aaron Hernandez have kept concussions in the headlines. Those players, in the end, talked irrationally, had dramatic mood swings, acted erratically with spontaneous violence or died of unnatural causes — even killing themselves or others."We were crusading on how to improve yoga, but we unearthed the cure for the concussion.” – Johnsen

tweet this

Posthumously, all were found to have suffered from CTE, a debilitating brain disease caused by repeated trauma.

Duerson and Seau, both in their mid-40s, shot themselves in the chest, sparing their brains for research. “Please see that my brain is analyzed by the NFL’s brain bank. Please,” Duerson wrote in a note.

Last year, Boston neuropathologist Dr. Ann McKee examined the brains of 111 deceased NFL players and published her findings in The Journal of the American Medical Association. All but one suffered from CTE.

“It is no longer debatable whether or not there is a problem in football — there is a problem" she wrote in her findings. "But there’s a lot to learn about CTE. Who gets it, who doesn’t, and why?”

According to Johnsen, concussions have nothing to do with toughness and little to do with equipment, and recovery from them has everything to do with genetics.

“CTE is too late," he says. "With the help of DNA, we can stop it before it starts.”

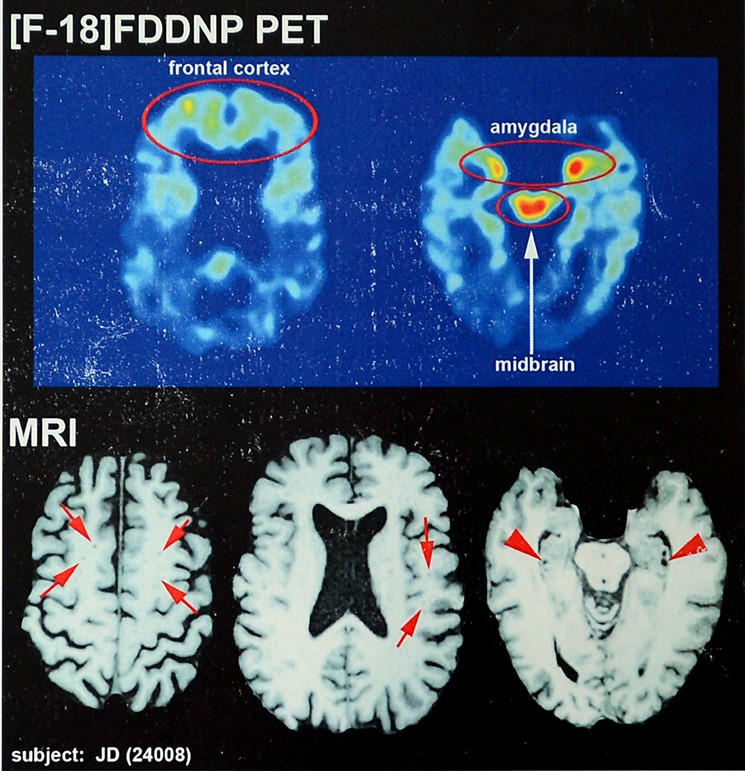

During Simplified Genetics’ research, the company consulted two brain specialists — Dr. Daniel Amen (neuroscientist and 10-time New York Times best-selling author) and Dr. Bennett Omalu (the forensic pathologist who discovered CTE in deceased NFL players and inspired the movie Concussion). Both directed Johnsen toward Apolipoprotein E (ApoE). ApoE is a protein produced by the body that helps transport fats between tissues. It has several subtypes, and one of them, ApoE4, has been correlated to the development of Alzheimer's disease and effects on the brain’s ability to recover from trauma.

Everyone is born with two sets of the gene that codes for ApoE subtypes, ranging numerically from 2 to 4. Possession of two ApoeE2 genes has been linked to the body's ability to repair damaged neurons, but those with two Apoe2 genes may be more likely to develop heart disease.

Those with even one ApoE4 gene (approximately 23 percent of the population) are eight times more susceptible to concussions, with elevated risks of dementia and Alzheimer’s and a lowering of the age of onset by 12-15 years. (The ApoE4 gene has been called the "Alzheimer's gene.") Although some studies have found a link to possessing two ApoE4 genes and the likelihood of developing CTE, ApoE4 is a long way from being nailed as a smoking gun.

Johnsen’s effusive marketing of his discovered link between genes and concussions lies somewhere between an evangelist and the guy at the State Fair of Texas Midway urging you to “step right up,” but science is more conservative.

Studies of ApoE have found correlations among the subtypes of the protein, Alzheimer's, heart disease and recovery from brain trauma, but they also note that other factors in the body's complicated chemistry are at work and not fully understood. For instance, not everyone with two ApoE4 genes ends up developing Alzheimer's. Not every retired NFL player who suffered CTE carried the genes. Other genes and other factors — the age a player took to the field, the number and severity of hits, how long he played, substance abuse — could be implicated.

There's still a lot of slow, meticulous research to be done. It's complicated by the fact that right now the only way to diagnose CTE is after death, so postmortem studies of NFL players' brains have a built-in bias. In the meantime, for parents choosing whether to let their kids knock heads in peewee football or NFL players trying to decide how many head shots they're willing to take before stepping off the field, knowing that their DNA puts them at higher risk could be invaluable information — or not. In a 2017 article on the website Medscape about the correlation between ApoE4 and CTE, some doctors pointed out that getting kids to exercise is hard enough, and keeping them off the field based on an inconclusive genetic test could have unintended consequences: Junior might die young and fat from a heart attack or diabetes, but with a pristine brain.

Johnsen isn't letting scientific caution hold him back.

“It goes back to our APY60 study,” Johnsen says. “Different football players can absorb the exact same hit to the head, but — based on their DNA and receptors — respond to it extremely differently. I’ll tell you this, if I had a son who was 4/4 [had two ApoE4 genes], I’d buy him the best golf or tennis lessons, but there’s no way I’d let him play football.

"Our whole point is that every parent should be armed with that vital information about their children. Think of it this way: If you were warned with 100 percent certainty that you would be 600 times more likely to have a car crash if you drove down a particular highway, wouldn’t you find an alternate route?”

Simplified Genetics’ new product was a test kit called Simply Safe, designed solely to determine potential athletes’ susceptibility to concussions and, more important, their ability to recover from them. For a one-time, $250 cheek-swab, Simply Safe purported to inform parents if their children were likely to be prone to long-term, concussion-related problems.“It is no longer debatable whether or not there is a problem in football — there is a problem. But there’s a lot to learn about CTE. Who gets it, who doesn’t, and why?” – Boston neuropathologist Dr. Ann McKee

tweet this

“It gave a concrete answer to the question on every parent’s mind,” Johnsen says. “Should I let my kid play tackle football? If we got the correct information and made the correct correlating decisions, in our lifetime, CTE in the NFL would be a thing of the past.”

When approached, neither Children’s Medical Center nor the Cerebrum Brain Center, a brain research and rehab center in Dallas, produced a doctor or scientist to speak to the intricate relationship between DNA and concussions or Simplified Genetics’ specific research and product. (As a rule, UT Southwestern doesn’t comment on outside studies.)

Enter Dr. Paul Roberts, a Birmingham physician who practiced for 20 years but since 2014 has been independently studying traumatic brain injuries. Roberts, who was previously aware of Simply Safe, said the test should be a mandatory part of routine physicals before children younger than 15 are medically cleared to play football.

“The data is conclusive; the evidence is definitive,” Roberts said in a recent phone interview. “If not [Simplified Genetics], some other company should be administering this test.”

Parents turning away from football

Football without violence is as unfathomable as a season of Ellen without vests. But Joe Theismann’s broken leg healed; Seau’s broken brain didn’t. The collisions still create highlights and attract fans, but the ensuing carnage is driving away players, alienating media and — most troubling for the sport — stifling youth participation.

“The NFL has real structural problems. I have an 8-year-old son, and there’s no way I’m letting him play football,” Dallas Mavericks owner Mark Cuban said during a local radio interview last October. “You can’t just sweep something like CTE under the rug.”

Former NFL player Ed Cunningham abruptly quit his 20-year career as an ESPN football analyst before the 2017 season, citing a mounting disdain for the violence.

“I can just no longer be in that cheerleader’s spot for football,” said Cunningham, who played with Duerson and against Seau. “In its current state, there are some real dangers: broken limbs, wear and tear. But the real crux of this is that I just don’t think the game is safe for the brain.”

Even respected NBC Sunday Night Football host Bob Costas delivered a hard-hitting take on the game’s state during a 2017 appearance on HBO’s Real Time with Bill Maher: “CTE is bad, potentially devastating news for the NFL. Football has to perfect equipment and rules and techniques to prevent the brain from rattling around inside a helmet, or maybe we’ll just get to a barbaric point where the players willingly assume the risk and we’re somehow OK with it, like the Roman circus with the gladiators fighting to the death. We’ll pay to watch it, but we won’t let our kids play it.”

In Johnsen’s Utopian NFL, the players are not predisposed to concussions and are essentially immune to any debilitating aftereffects. By making its players safer, Simply Safe would have made the NFL safer.

But what about current players and longtime veterans? Johnsen believes the potential fallout from that question led to his product’s premature demise.

In a 2013 position paper, the American Academy of Neurology wrote that NFL players with multiple concussions and the presence of ApoE4 should be “counseled into consideration of retirement.” The statement — endorsed by the NFL Players’ Association and American Football Coaches’ Association — echoed Johnsen’s premise: Playing football with ApoE4 is akin to wearing a defective helmet.

The pre-emptive defense of Simply Safe seems undeniable, but breaking the news to a veteran player that he is ApoE 4/4 would be daunting because no real evidence exists to suggest that players can halt — much less reverse — the inevitable onset of CTE caused by repeated concussions. Widespread testing of current players could potentially lead to mass retirements among those revealed to have at least one set of ApoE4 genes. The quitting of high-profile, aggressively marketed players such as Cowboys quarterback Dak Prescott because of heightened, personal long-term dangers would be a public relations nightmare for the NFL.

Johnsen believes the NFL feared not the eventual two steps forward his product would prompt but the potentially devastating one step back.

“I would imagine most of the families of the victims of CTE would’ve liked to have known about the player’s ApoE before or during their career,” Johnsen says. “Had he tested 4/4, Seau might have chosen a different sport. Shame, because he’s a football Hall of Famer. But on the other hand, he might be alive today.”

No sale

One of the 111 NFL brains that McKee studied belonged to a former linebacker for the Houston Oilers and Kansas City Chiefs named Ronnie Caveness. He died in 2014 from melanoma but also suffered a long bout with Parkinson’s disease, which has been linked to the CTE McKee identified in his brain. In college, he was an All-American who helped the University of Arkansas go undefeated and win the national championship in 1964.Caveness’ teammate and captain on that Razorbacks title squad was a man who recently — despite the growing mountain of scientific evidence — labeled any connecting of the dots between concussions and CTE and mental health problems and suicide as “absurd.”

His name is Jerry Jones, and Johnsen suspects his influence is partially why Simply Safe is no longer on the market.

Equipped with his company’s revelations and ready-for-market product, Johnsen took the first step in December 2015 toward his goal of having the test kit not only widely available but also endorsed by the NFL. He emailed old acquaintance Anderson with details about Simply Safe.

“My whole thing was to get some awareness,” Johnsen says. “I didn’t need any funding for research. I just needed a stamp of approval.”

According to Johnsen, Anderson immediately acknowledged receipt of the email and promised to “be in touch.”

“That in itself was a big relief and a sort of accomplishment,” Johnsen says. “At that point, at least I knew that the NFL knew.”

The next day, he received a call from Jennifer Langton, at the time the NFL’s senior vice president of health and safety.

“It was like my life flashed before my eyes,” Johnsen says. “All the time and effort and research and money and hope. I got pretty emotional.”

The conversation that took a lifetime to arrange lasted all of seven minutes. Langton informed Johnsen that the league had already issued its grant money for concussion-related research.

“No, you don’t understand,” Johnsen says he told Langton. “I’ve analyzed the research. I’ve already got the product. I don’t need money or grants, just some exposure. Some good press. To let parents know they can get accurate information on whether to play football through a simple, one-time test. An endorsement from the NFL would open so many doors. I’ve got your long-term fix for concussions. Right here. Right now.”

By Johnsen’s account, Langton was polite and professional and … never heard from again.

What came next was an email from the Food and Drug Administration. In Johnsen’s assessment, it was a stern reminder about the nine zeroes having its way with the five.

Johnsen says two days after his Langton call, he received the electronic missive from the FDA, directing Simplified Genetics to participate in a conference call.

“I knew I was screwed,” Johnsen says. “I felt like the NFL ratted me out to the principal’s office.”

To make matters worse, Simplified Genetics’ chief medical officer was attending a family funeral and couldn’t join the call. Immediately, Johnsen says, the episode deteriorated into Butch Cassidy and the Sundance Kid holed up in that tiny corner as the entire Bolivian Army amassed in the courtyard of their imminent graveyard. Only without Butch Cassidy.

“I knew I was screwed. I felt like the NFL ratted me out to the principal’s office.” – Johnsen

tweet this

“I’m not exaggerating; there were 12 doctors and two lawyers on the other end of my phone, all reciting their degrees and commendations and aiming them right at me,” Johnsen says. “It became clear this wasn’t going to be an open discussion or any constructive dialogue. This was nothing but an intimidation tactic. A very effective one.”

Johnsen might as well have been trying to sell online advertising to an Amish bookstore.

He says the FDA’s platoon accused Simplified Genetics of illegally dispensing medical advice, questioned whether the company’s DNA swabs were FDA-approved (they were) and passive-aggressively warned him not to take on the NFL.

The FDA did not respond to an email request for comment.

“We had done everything right, above board and in line with regulations,” Johnsen claims. “But the FDA could shut down McDonald’s if it wanted to. My little company couldn’t afford one week in court against their lawyers. At that point, we had sold less than $1,000 of Simply Safe. I wondered why the FDA was wasting its time on us, but all I really worried about after that call was not having the whole company shut down.”

Johnsen immediately removed Simply Safe from his website and halted plans for an extensive marketing push.

“I didn’t exactly go out guns a-blazin’,” Johnsen says. “But my plan was to surrender the battle, then to win the war later. I know our product could help the NFL. I still wonder the real reason they didn’t at least hear us out.”

He never again heard from the FDA, but with his signature product shelved, Simplified Genetics ceased operations two years later.

“I don’t have a clue. It makes no sense," Roberts said regarding the reasons Simplified Genetics didn’t receive support from the NFL or FDA. "You’d think a company aiming to make a sport safer for children would be welcomed with open arms.”

Anderson declined to be interviewed. Through a Cowboys spokesman, she said she remembers Johnsen from the cheerleaders' yoga training but doesn’t recall any encounter or communication pertaining to DNA. Per protocol, according to the spokesman, Anderson refers all health and safety issues to the NFL office in New York.

The NFL didn’t respond to an email request seeking comment on its dealings with Simplified Genetics.

“Turns out I funneled my information through the right person,” Johnsen says, “but the wrong daughter.”

Jerry Jones weighs in on science

After its alleged stiff-arm to Simply Safe in 2015, the NFL continued grappling with CTE.By 2016, it had been seven years since the league publicly admitted the possibility of a connection between repeated concussions and CTE; five years since the gruesome, eye-opening suicides of Duerson and Seau; and three years since the league paid its record settlement to former players.

In March 2016, Langton’s successor as the league’s health and safety czar, Jeff Miller, was asked at a hearing on Capitol Hill in Washington if there was a definitive link between football and degenerative brain disorders like CTE.

“The answer to that is certainly, yes,” Miller said.

It wasn’t, however, a unanimous decision.

Jones won three Super Bowls. He positively affected the sport as much as any owner in NFL history and was enshrined last summer into the Hall of Fame. He turned his $140 million investment to buy the Cowboys in 1989 into the most valuable sports organization on the planet, valued by Forbes at $4.2 billion.

But at the NFL owners’ meetings just 10 days after Miller’s seemingly definitive pronouncement, the Cowboys owner sat in defiance of science.

“We don’t have that knowledge and background, and scientifically, so there’s no way in the world to say you have a relationship relative to anything here,” Jones said when asked about CTE and Miller’s statement. “There’s no research. There’s no data. … We’re not disagreeing. We’re just basically saying the same thing. We’re doing a lot more. It’s the kind of thing that you want to work … to prevent injury.”

An incredulous reporter pushed him, asking if the owner believed in the scientifically proven correlation between repeated brain trauma and flawed, fatal decision-making by former players.

“No, that’s absurd,” Jones snapped. “There’s no data that in any way creates a knowledge. There’s no way that you could have made a comment that there is an association and some type of assertion. In most things, you have to back it up by studies. And in this particular case, we all know how medicine is. Medicine is evolving. I grew up being told that aspirin was not good. Now I’m told that one a day is good for you. … I’m saying that changed over the years as we’ve had more research and knowledge.”“We don’t have that knowledge and background, and scientifically, so there’s no way in the world to say you have a relationship relative to anything here.” – Cowboys owner Jerry Jones

tweet this

To the chagrin of Johnsen, one of the most powerful men in all of sports refused to realize that DNA doesn’t waver.

“When it comes to who you are and what you are, the building blocks of your genetic code are pretty damn rigid,” Johnsen says. “Zero wiggle room, in fact. He’s right in that the medicine used to treat CTE will likely evolve. But the correlation is there. On that there’s no going back. My path to get the NFL to validate our DNA concussion test went right through Jerry, a man who still doesn’t believe there’s a problem.”

A year later, during his Hall-of-Fame induction speech in Canton, Ohio, Jones took particular time to praise his daughter.

“She’s as much a part of securing the future of our game regarding health and safety, respectively, as any person in this country,” Jerry said of Anderson. “I’m deeply grateful that the NFL gives her the opportunity to be involved at the league level to make a difference. For some of the mothers that are thinking about signing that permission slip for football, you need to listen to Charlotte and observe what she does to ensure a safe future for our sport, certainly at the level of youth.”

Health and safety? Mothers and permission slips? Safe future and the level of youth? Johnsen said he cringed at the speech, remembering all too well what Anderson did and the NFL didn’t do with Simply Safe.

“To want to use my test and not have it is a shame. But to have my test and not want to use it is a crime,” he says.

In 2018, the NFL anticipates revenues pushing $15 billion.

In 2018, sales from Simply Safe will be $0.