"You're saying I died?"

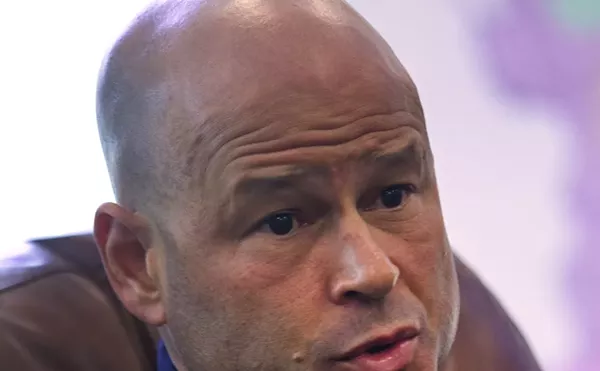

Michael Sorrell was lying in a bed at Methodist Hospital. It was September 14, 2008, and he had been unconscious for the better part of 72 hours. His chest had been sliced open, a battery-operated cardiac defibrillator implanted above his ribs. A nest of wires snaked in and out of his arms and torso.

Iron Man. He felt like Iron Man.

"What happened?"

Doctors tried to explain. He had suffered from a cardiac episode, they said. His girlfriend, Natalie, was by his side. She tried to explain, too.

She had been there that night, at his house in Oak Cliff. She awoke to Michael lurching in the bed, drowning in air. She dialed 911 and pressed her lips to his, forcing air into his lungs and thrusting against his chest the way she learned working summers at the pool in high school. She watched the medics place paddles on his chest to shock his heart. Still, he flat-lined. She looked at his lifeless face and his ashen bald head as they lifted him onto a stretcher and wheeled him down the driveway.

Really, though, his chart said it best.

Michael Sorrell. Sudden cardiac death. Patient had to be revived.

"Death?" Sorrell asked, seething. There were too many reasons why he couldn't die. He was tall and strong and smart and handsome. He had Natalie, who would soon be wearing the ring he'd already picked out. And he had dedicated the last 18 months of his life to Paul Quinn College, South Dallas' Historically Black — and Historically Corrupt and Historically Broken — college. He'd come on as a temp, as the interim guy, and had ended up as The Guy. His changes were just starting to take hold.

"How is this now my life?"

The doctors weren't sure. He might've had a genetic predisposition to an irregular heartbeat, but there was no way to check. His mother, his father and his grandparents were all dead. The doctors agreed that stress was a factor. Too much work, too little sleep. He was only 41, but his heart just gave way.

A year and a half earlier, on a warm spring morning, Sorrell exited Interstate 45 South onto Simpson Stuart Road in South Dallas. He passed a boarded-up gas station and a neighborhood of small, dilapidated houses and made a right onto the driveway that led to the Paul Quinn campus. It was 9:30 on his first day as president. He didn't want to be there any longer than his 90-day term, but he was still anxious. He pulled up a hill.

He noticed the abandoned buildings first. They were everywhere, boarded up, glass smashed out and lying on the ground, tall patches of foliage growing on the roofs. They were visual reminders of the campus' past: For 27 years this was Bishop College, a historically black Baptist school that provided thousands of African-Americans with an education and delivered many of them to Jesus Christ.

Then came the jackals. Embezzlers siphoned thousands of dollars, and the school finally collapsed in 1988. The property was auctioned for $1.5 million to Comer Cottrell, a black mega-millionaire who made his fortune in hair care. Cottrell donated the land to Paul Quinn College, a historically black school down the road in Waco.

Paul Quinn is the oldest historically black college west of the Mississippi, originally founded in 1872 by African Methodist Episcopal preachers. But like Bishop, the school had stumbled financially. Its president promptly moved its 1,000 students to Dallas, where it would theoretically have more students, and more money, from which to draw. But it couldn't populate the buildings, and it couldn't afford to do what probably should have been done: blow them up. So on that March morning, the school's abandoned buildings greeted Sorrell as sentinels, witnesses to two schools' dysfunction.

He took a tour of the grounds. He started in the dorms, where he found rooms with holes in the walls. Not cracks or punctures, but large, gaping holes in the drywall that had been punched through with fists, furniture and bodies. What students he found were mostly still in bed. No wonder the campus felt deserted.

I wouldn't let my son live here, he thought, even though he didn't have a son. He had grown up in Chicago, an upper-middle-class kid whose parents both owned businesses. His father owned a barbecue restaurant and was dedicated to his store, working or sleeping through all but one of his son's varsity basketball games. His mother owned a social work agency. She was the one who stressed education to Sorrell and his sister.

Sorrell, 6-foot-4 and well built, was recruited to play basketball out of high school. He was the first member of his family to eschew Historically Black Colleges and Universities, or HBCUs, for a "white school," starting at Oberlin, the liberal arts mecca in rural Ohio, and going on to Duke for his master's in public policy. The day of his graduation, his mother hugged him and held him close.

"This is great," she said with pride. "But don't forget you're going to law school next."

He was 40 now, years removed from the bar exam, but he still remembered living in flawless dorms overlooking perfectly manicured lawns. Leaving Paul Quinn's dorms, he noted that no one had even bothered to cut the grass ahead of his arrival.

He walked to the student union. The hallways needed sweeping, and the walls were painted a dark, dirty yellow. In the fitness center, all the bars were bent. He tried to grab lunch in the cafeteria, but the food was repulsive. Students sat on folded, metal chairs and huddled over flimsy card tables to eat.

He made his way back to his office. His phone didn't have call-waiting.

Seriously? he thought. I don't remember the last time I didn't have call-waiting.

He'd bounced around law firms all over Dallas in the 13 years since finishing law school. He'd worked in the White House, on different leadership committees across Dallas, on the Olympic bid committee. Suddenly none of that meant anything.

He called the CFO into his office. He wanted to discuss the year's budget.

"We don't have a budget," the CFO told him.

"It's March. How can you not have a budget?"

He found a copy of the school's course catalog. It listed classes that were no longer offered at Paul Quinn, and some that had never been offered. He met with teachers, who told him they were afraid to go to the bathroom, fearing their purses and desks would get ransacked by students. (It was common at the time for people who didn't attend the college to walk freely around campus.)

Sorrell thought back to Oberlin, where he once had dinner with Johnetta Cole, the president at Spelman College, an all-female HBCU in Atlanta. Ever since then he'd toyed with the idea of being a black-college president, a rainmaker for young black people. Maybe when he was in his 60s, old and fat and not much use to anyone.

But not now, not when he was about to get the Grizzlies. He and some business partners had placed a bid on Memphis' NBA team. News reports characterized Sorrell as the attorney for the group's leader, but he says he was going to be president and rebuild the franchise. He could close his eyes and imagine the apartment where he would live, in a high-rise overlooking the Mississippi.

This was just 90 days of clean-up. Sorrell had a reputation as a fixer. His last position had literally been Chief Problem Solver for a sports management firm called Victor Credo. That's why the chairman of the college's board, AME Bishop Gregory Ingram, had made him the 34th president of the school — the fifth since 2001.

Before he went home that night, Sorrell was handed a set of keys. There weren't electronic locks, so he had to close and secure the door to the building with a padlock, wrapping the links of a heavy chain around the entrance's handles. It was laughable. And yet.

Nowadays, there are no strangers milling about Paul Quinn. This is no longer a school you can just visit on a whim.

To get onto campus you have to drive down Simpson Stuart Road like Sorrell did, and through a 10-foot electronic gate that shuts the school off from the city. It's sometimes operated by one security guard, but usually two, both of whom wear skullcaps and heavy jackets because they have to keep walking outside to head off approaching cars. No one gets in without an appointment, and no one roams untethered.

If a visitor does arrive with an appointment, the nice lady guard calls up to the administration building. She opens the gate, gets in her security sedan and motions for the visitor to follow. At the administration building, she gets out and holds the door, and they walk in together, up the closest flight of stairs, down a couple of hallways with black tile and purple and gold trim. There's not a single student in sight.

After 15 minutes or so, Sorrell emerges.

"Hey, man, how you doing?"

And it's cliché, but he swaggers, with his shoulders kind of bent forward and rolling. He sees an extended hand and grabs it, bends down and pulls in for a hug that's smothering, imposing. And damned if he isn't a good hugger.

His office is cavernous, with plaques, pictures and newspaper articles marking past successes. A gavel balances on a cinder block on the edge of his desk, front and center. There are photos, faced away from him and toward his audience, photos of him, of him with his wife, of him with his wife and President Barack Obama. The desk is dwarfed by his high-backed burgundy leather chair, which looks like it was imported straight from a courthouse. It's tall, but he's tall.

He leans all the way back and speaks barely above a whisper. He looks through his glasses and down the bridge of his nose and finishes almost every sentence with "Right?" He talks about his days playing basketball, and offhandedly reveals that he was one of the best players of all time at his college. He could've been even better if he hadn't gone to Oberlin.

"I didn't look at it and say, 'I'm going to be the best basketball player I can become.'" He pauses. "I looked at it and said, 'That's the best man I can become.'"

"You said that at 18?"

"I was 17."

When he took over Paul Quinn, Sorrell says, the school had 30 days of cash left. The Southern Association of Colleges and Schools was preparing to put the school on probation that summer. (He'd have to sue SACS to keep the school from closing.)

Enrollment had fallen below 600, and in Sorrell's first week on campus, it was about to fall further. There'd been a fight at school, and 11 students were suspended. They came before Sorrell, in this very office, to make their cases for staying. It was a chance to keep enrollment steady while he righted the ship.

"Listen," he recalls telling them. "Let me apologize to you. If you have been led to believe that you are what a college junior should look like, you have been deceived."

The boys showed up late to the meetings, Sorrell says. Most were wearing wrinkled clothes, like they'd just gotten out of bed. Some didn't bother to shower or comb their hair. The appeals documents themselves were horrific, full of bad grammar and misspelled words.

"And while I didn't know you, you were at my institution and I accept responsibility for that. But you are not what this institution is going to produce."

He kicked them all out.

Summer approached. His 90 days were winding down. Sorrell says he was ready to get back to the Grizzlies, but in the meantime he attended Friendship West Baptist Church. The pastor there, Freddie Haynes, was on the school's board of trustees. Every Sunday, Sorrell says, he would sit in the pew, and Haynes would find him from the pulpit. Their eyes would lock as Haynes spoke about the importance of people following God's plan.

And then the Grizzlies bid fell through. So he just kept working.

"August, we couldn't even pay our full payroll, right?" he says, leaning back, semi-supine. "I had to cut everyone's salary for that whole next year. I cut my own salary by 25 percent. The VPs got their salaries cut by 20. Our directors 15, 10 percent for our faculty — everyone took a pay cut."

He says they grumbled, but it's hard to know. The school's website provides no information about or contact information for its faculty, and efforts to interview staff are met with reams of red tape. Lori Price holds the tape. She's Sorrell's friend of 17 years and his chief of staff. She refers to him only as President Sorrell. He calls her Lori.

It's Price who gives a tour of the grounds, during which there is no interaction with anyone but her. She also arranges all interviews, which she schedules back to back in a glass conference room with hand-selected faculty and students.

Dr. Kizuwanda Grant, the school Vice President of Academic Affairs, says Paul Quinn was her calling. "If I ever felt like I was going to accomplish something, it was going to be at Paul Quinn."

Maurice West, Dean of Men, is a Paul Quinn alum from the last of its Waco days. He coaches track and teaches, among other things, business etiquette. (He also offers his visitor an unsolicited appraisal: "Your collar needs pressing.")

The students come next. When Sorrell took the job, Paul Quinn had open rolling enrollment, which meant that if you could pay or get a loan, you could attend, no questions asked. The policy was a throwback to the years after the Civil War when HBCUs were created for black kids who had no other higher-education options.

When Sorrell took over, only five seniors were eligible to graduate. Students were coming to school just because they were kicked out of their homes, were bored or had no place to go. They would enroll, grossly unprepared, and would fail, get in fights or just stop showing up.

He implemented an admissions policy and created an admissions department to enforce it. To be considered, applicants needed a 2.5 GPA, a 500-word entrance essay, a letter of recommendation, an interview and, oddly, a headshot. Failing students didn't get in. Students who couldn't write didn't get in. Some students sent photos of themselves in T-shirts or wielding guns. They didn't get in, either.

It was also common for students to enroll for just long enough to receive their loan checks. As a result, the school had almost $1 million of uncollected student receivables, which had destroyed the school's credit rating. So every student who owed money got kicked out.

Some of the remaining students are paraded into the conference room. They're upperclassmen who stuck around when Sorrell was cleaning house, when their friends packed up and left in droves. They recall the way he enforced a business-casual dress code, punishable by a $100 fine or 40 pushups, for which students had to push up from the floor, clap once, and catch themselves. They remember Sorrell laughing as students grunted their way through the calisthenics, cackling, "Catch yourself or break your face!"

They also tell stories of Sorrell's kindness. Keeston McKinnon went into Sorrell's office his freshman year before the 2009 Christmas break. McKinnon lived in Detroit, and his family didn't have enough money for him to travel. Sorrell set up a traveling stipend for students who couldn't afford to travel.

"He's bought my ticket every year," McKinnon says. "He's never asked for anything in return."

Ronisha Isham tells another story. One time, Sorrell was speaking in the student union during an event in the grand lounge. He noticed one student in the front row squinting.

"How many kids can't see me right now?" he asked. He remembered being nearsighted as a kid.

It turned out 10 percent of the student body needed glasses. He raised $5,000 in 10 days through Facebook and Twitter to outfit them with eyewear.

Isham also has a severe walking disability. She has to take a step, open up her hips, and swing her trail leg all the way around, before repeating on the other side. She was having trouble getting around campus. He bought her a bike.

Today, there are fewer than 200 students enrolled at the school, and more than 90 percent of the staff is new. The ones who Price allows to be interviewed are fully bought in, automatons of righteousness. Sorrell wants 2,000 kids enrolled by 2020. He even has a name for them: Quinnites.

North and South Dallas have long existed as separate entities, sharing only a name. Their jurisdictions stop at the river, and rarely do the two overlap. When they do, it's usually for a nice dinner or a political clash. And when there's a clash, there's a cadence that follows, a dance that everyone knows and respects.

It happened last summer. The city, facing a budget shortfall, proposed a law that would require every commercial trash hauler to reroute their trucks to McCommas Bluff, the city-owned dump. The law would earn the city as much as $18 million a year in tipping fees. The cost: Every commercial hauler would now trudge through South Dallas, to a dump less than two miles from Paul Quinn.

Those who know the cadence know what happened next: Out came a small but vocal faction of activists, who tried to rally an oft-exploited community. Then came the olive branch, stretching south across the river and studded with dollars.

"When black people get hot, City Hall gives the preachers some money to cool them down," says civil rights activist Reverend Peter Johnson, who scornfully calls South Dallas preachers "the city's firemen." The preachers in turn soothe their congregations, cutting the legs from under the fighters.

"That's the Dallas way," he says. "That's as much a part of Dallas culture as cowboy boots."

This time the cool-down came with a name: the Southeast Oak Cliff Stimulus Fund. To appease South Dallas, the city promised to redirect up to $1 million from the new revenue into the fund. With any luck, whichever South Dallas residents who knew or cared about the shit mountain headed their way would be won over by the stimulus fund.

But then the black kids showed up.

Sorrell first heard about this plan — the city calls it "flow control" — from a reporter looking for a scoop: "How do you guys feel about the fact that the city is going to reroute all the garbage from the city to the McCommas Bluff Landfill a mile and a half from your campus?"

"What?" Sorrell asked. He had never heard of flow control.

"Did anyone bother to fill you guys in?"

At the time, Sorrell was teaching his Introduction to Quinnite Servant Leadership course to 13 incoming freshmen. Quinnites among Quinnites.

After hearing from his reporter friend, Sorrell addressed this class.

"This is a big deal," he remembers saying. "All the garbage in the city is going to be a mile and a half from our campus. I signed up to go speak down at City Hall during a hearing on this." The hearing was during class time. No problem. He told the class they were coming, too.

Sorrell arrived at City Hall flanked by Quinnite Nation. The 13 freshmen attended, as well as most of the summer faculty — about 45 people in all.

"Where's the impact study?" he railed. "What happens to the community when you make this decision, right? How does it affect the quality of life? How does it affect development prospects? How does it affect us?"

The city postponed a decision to get more feedback from the public, so the freshmen decided to host a town hall meeting in the Paul Quinn student union. Sorrell supported the idea, but he warned them.

"If you're going to do this, the issue you're concerned about is turnout," he remembers saying. "You don't want to hold a town hall meeting with 12 of your best friends and think that people are going to take you seriously."

They had the meeting on campus in the grand lounge in the student union. More than 250 people showed up. Deputy Mayor Pro Tem Tennell Atkins was on the panel, as was the head of the city's Sanitation Services, Mary Nix; and Assistant City Manager Ryan Evans. It was the largest South Dallas community meeting anyone could remember. The Quinnites even live-streamed it, and the panel took questions from the audience via Facebook, Twitter and text message.

There was some skepticism about their enthusiasm, and Sorrell's role in it. Bob Weiss, the chairman of the school's board, says he heard accusations that the students had taken money from waste haulers. "You cannot tell any historically black school not to be involved in social justice," he says.

There's also suspicion that Sorrell has something bigger planned: a run for Dallas city council or some other office. He had been prepared for office, from his Harvard fellowship to his public policy days at Duke to the four boards around Dallas on which he serves. He had bided his time for the last four and a half years, the theory went, and this was his coming-out party as a champion for the poor and underrepresented.

"It takes my breath away," Weiss says of the skepticism. "For whatever reason, people don't want to see Paul Quinn succeed."

Or maybe they just don't believe it can. Paul Quinn, like Bishop College before it, has a rich history of presidents and politicians stealing from it. (James Fantroy, a city councilman, died in 2008 shortly after a prison stint; he was convicted of embezzling more than $20,000 from the school.) It's because of this toxic reputation, Sorrell says, that he reflexively kept people at arm's length.

When Peter Johnson met with Sorrell in 2007, Johnson says he had already lined up materials and manpower to fix the crumbling roads in and around Paul Quinn. Johnson says Sorrell showed up two hours late for the meeting, didn't apologize, and never spoke to him again.

Sorrell says he doesn't remember the meeting happening, but that it could've happened. Johnson also claims the 10-foot gate was his idea.

"When we got started, things were extreme," Sorrell says. "There were lots of people who came by, telling me we could do lots of things. Ninety-nine percent of those people couldn't do jack." The experience made him judicious when he met with suitors in his presidential office, he says.

"I didn't have a margin of error, right? I couldn't get it wrong. A lot of people try to come in and make money off of us. And I am very clear: 'We're not paying you jack.'"

It didn't appease his skeptics that Sorrell then accepted money from philanthropist Trammell S. Crow. Crow donated $1 million to Paul Quinn in 2010, the largest single gift ever, for Sorrell to demolish 15 abandoned buildings. (Crow refused to be interviewed, citing a previous dispute with this newspaper.)

"The money was great, and we appreciate it," Sorrell says of the donations. "But what meant the most to me was, here's this guy who doesn't have to believe. But he got it, right? He believed. And I'm one of these people, if you believe, I will run through a wall for you." They went out to lunch when Sorrell was new to the school, and they've been friends ever since.

The perception was compounded when Bob Weiss was voted in as chairman in January of 2010, two months after his employer, the Meadows Foundation, donated $500,000 to the school. The college had never elected a chairman who wasn't a member of the African Methodist Episcopal Church. Weiss is a Jew from North Dallas.

"I don't think those schools can survive having to depend on white corporate dollars," Johnson says. He wants the black schools to be supported by the black community, "and not be dependent on whether or not we piss some white man off who'll cut the money off."

Flow control would eventually be shot down by the courts, but not before Sorrell got one more march in. When the 2011 school year started, Sorrell showed up at City Hall again, and this time he brought the whole campus. They even wore custom-made shirts. They read, "I Am Not Trash."

"I almost bought it," Sorrell kept saying in that hospital bed. "I almost bought the farm."

When most men would have taken time off, maybe moved to Tahiti, Sorrell kept working, and he kept skipping out on sleep. He even started teaching. It wasn't until he married Natalie and had his first son, Michael, that he listened to his doctors.

But even then he kept teaching.

Last fall, during the first week of his Business Seminar class, he assigned his students to read the Sunday New York Times. They'd be quizzed on the paper on Monday, he said. He'd pick one article. If they could properly demonstrate they'd read it, they'd get an A. If they couldn't, they'd fail.

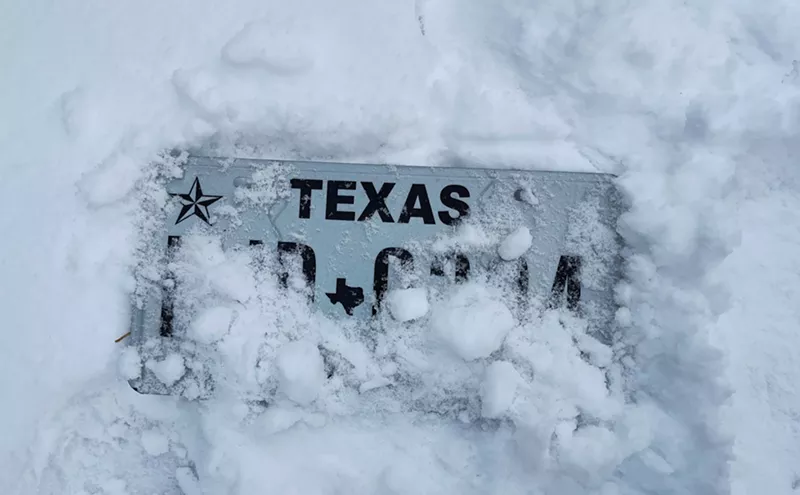

That Sunday morning, the students piled into cars in twos and threes and headed to the nearest newsstands, but they couldn't find the paper. Two friends, Ryan Carrington and Valette Reese, were the most tenacious. They checked every gas station and convenience store they knew in South Dallas. They drove north on U.S. 75, stopping at every exit, until they reached a Walmart 10 miles north. They kept driving, searching, and couldn't find the Times anywhere. They showed up in class on Monday empty-handed, fearing Sorrell's wrath, an F, a batch of Quinnite pushups.

Sorrell just laughed. He knew his students wouldn't find it. Not in South Dallas. He wanted to test their persistence and to see if anyone would actually cross the Trinity on their quest. And he wanted them to think about what it meant that something so ubiquitous on one side of the river was practically nonexistent on the other.

There's something else his students can't find that nags at Sorrell: food. He tells the story of Dexter Evans, Paul Quinn's student-body president, an Army Reservist and the most recognizable face in the small student body. In his first year, Evans lived off campus, in a nearby low-income apartment complex. He didn't have a car, Sorrell says, so he walked to class everyday. To buy food he had to walk down Stuart Simpson Road, past the boarded-up Popeye's, deserted but for the occasional foraging stray dog, and to a convenience store.

"It was personal to Dexter; it was real to Dexter, right?" Sorrell says."He lived this experience."

That Sorrell might try to use Paul Quinn to water South Dallas' food desert makes sense to anyone who's traversed it. But not how he did it. Not at an HBCU. Not in Texas.

It started in the spring of 2007, when he did the unthinkable: He cut the school's football program.

"With athletics, you have to ask yourself, 'Can we ever be great in this?'" he says. "'Do we have the resources to allocate to it to be able to be great? And even if we were great, would anyone care?'" The team underperformed in every area, was at the center of most disciplinary problems and burned $600,000 a year. Dead weight; they had to go.

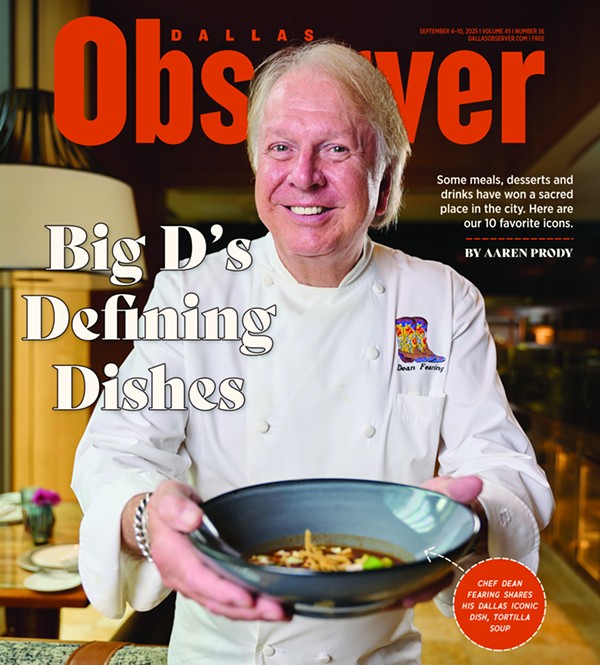

Then, in May 2010, in a sort of Texas-style reverse-Field of Dreams move, he dug up the football field and turned it into a farm. The school promised 10 percent of its yield — kale, spinach, potatoes, watermelon, arugula and more — to neighborhood families and food banks.

"We're adding a greenhouse, solar panels and irrigation to the farm, right?" Sorrell says. Within the next two years, he hopes to open up a Quinnite-run grocery store. It will be the school's coming-out party, he says, its redemption for years of corruption and uncertainty.

For now it's just a farm. Still, that old football field is almost unrecognizable. All that's left are two goal posts, a bleacher stand and an old scoreboard.