We’ve had many new terms worked into our daily vocabulary since the pandemic, such as flatten the curve, pivot and social-distancing. Now “compliance” is on deck. It was brought up several times last week at the Dallas County Commissioners Court meeting while Dr. Philip Huang, the director of Dallas County Health and Human Services (DCHHS), briefed the court on COVID-19 trends. A major factor to changing the trajectory for the spike is “compliance” or its lack.

In June, the county health department and Parkland Health and Hospital System launched a contact-tracing plan that involved hiring more than 250 people to work in a 27,500-square-foot office building that was previously home to a telecommunications company. The $10 million to fund the project came from federal coronavirus relief money.

The plan is to carry out a massive contact tracing effort allowing for real-time data on hotspots, ultimately blunting the spread of the virus. Contact tracing is a widely supported model, especially by the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. After masks and social distancing protocols, and until we have a vaccine, contact tracing is a major player.

The DCHHS and Parkland plan involves contacting via text, phone call or email those who have tested positive for COVID-19. They’ll receive a health survey that requests information on people they were close to just before getting sick. It’s all confidential, and the person doesn’t have to give their identity to their close contacts.

Then, the center contacts those people and, according to its site, asks them if they have symptoms and offers guidance on testing, treatment and self-isolating.

Timing is crucial with contact tracing. Test results need to be turned around in 24 hours, allowing the tracers to track down the contacts quickly. (Bill Gates told Wired magazine that if a company can’t turn around a test result in 48 hours, they shouldn’t be paid for it, calling results after two days “garbage.”)

Also, dealing with several hundred new cases a day is much more reasonable than dealing with the anticipated cold-weather surge of 1,000 new cases a day. In a commissioners court meeting in August, Assistant County Administrator Charles Reed said the program was built based on a model of 192 cases a day.

Finally, the surveys must be completed and returned quickly so the tracers can do their jobs. Herein lies a problem: Of the more than 48,000 surveys that have been sent out, only 19,000 have been completed.

“We’re not even at 50% of people who we’re sending them out,” Commissioner John Wiley Price said, clearly agitated last week.

Price pressed Dr. Huang on how we get that response rate higher. Huang implied the program is still sputtering to a full start, adding that getting all the data merged and streamlined is very complicated, but once everything is in place, it will be a “state-of-the-art” program. The commissioners kept bringing up the word “compliance,” the one factor no one can control. Voluntary compliance is a harbinger here.

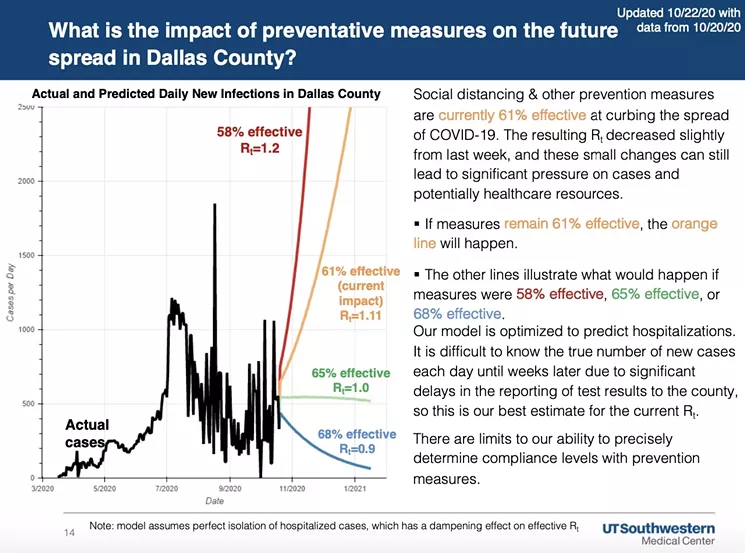

This chart shows the effectiveness of preventive measures at different levels of compliance.

UT Southwestern Medical Center

Last Friday, UT Southwestern updated case projections through the end of the year. They also looked closely at prevention measures, such as social distancing and face masks, and estimated those things are 61% effective at curbing the spread of COVID-19.

At that rate, their modeling projects 1,200 new cases a day by Nov. 3, climbing to 2,500 cases by the end of the year, a catastrophic scenario for the local healthcare system and public.

However, with just a four-point increase in the effectiveness level to 65% — by persuading people to follow the measures — cases flatten at just over 500 per day then slowly trend down. At 68%, the cases drop like the far side of a roller coaster.

The final line of UT Southwestern report tells all: “There are limits to our ability to precisely determine compliance levels with prevention measures.

"Further, as we head into winter, the community’s continued compliance with physical distancing, masking, hand hygiene and crowd management policies are especially needed to ensure healthcare capacity remains available.”

And part of that compliance means answering the health survey should you get one. But, even that may be too late already.