Courtesy of William Waybourn

Audio By Carbonatix

The staccato thud of hammers broke the predawn stillness one morning in 1988. Activists dotted the vacant lot. They carried some 700 hand-painted white crosses bearing the names of Dallas County residents who’d succumbed to AIDS. Members of the Gay Urban Truth Squad (GUTS), a Dallas activist group, drove the wooden stakes into the dirt at the intersection of Lemmon and Cole avenues. GUTS leader William Waybourn remembers the sun crawling over the horizon, its rays catching the crosses. Their shadows stretched across the grassy field, he says: “It was a beautiful day.”

For years, the empty lot was home to a large hole that had filled with stagnant water, an eyesore landmark brought by a development project gone south. The Dallas Morning News had dubbed it the city’s own “Grand Canyon.” Dallas City Council approved spending $500,000 to pack the crater the same year it had devoted just $55,000 toward AIDS funding, according to a 1996 D Magazine article. Media swarmed the makeshift potter’s field, which was featured on the evening news. The city was so embarrassed by the demonstration that they left the crosses up for a couple of days, Waybourn says, laughing.

But it worked. Officials spiked AIDS support to $552,000 the following year.

The group’s genesis rested in another gay rights organization called ACT UP (AIDS Coalition to Unleash Power), which was located in cities like New York, Los Angeles and San Francisco, Waybourn explains. Being the “good Dallas boys that we were,” he says, they asked for permission to use the name. No luck. So, GUTS was born, which some joked stood for “Gay Urban Terrorist Squad.”

“We were not popular,” Waybourn says.

Like the potter’s field, other GUTS demonstrations were equally colorful and effective. They shut down an airport terminal on Thanksgiving Eve. They fashioned roughly 100 dummies out of clothes and rags and dumped them outside the county health department. They sketched chalk outlines outside City Hall Plaza, again representing the ever-increasing number of AIDS cases. Then-Mayor Annette Strauss accused the activists of defacing public property, but she eventually backed down after taking flak, Waybourn says. The macabre contours washed away in the rain.

Activist Bruce Monroe recounted that GUTS members drew some 1,200 outlines during the City Hall demonstration, according to LGBTQ+ history website The Dallas Way. The city threatened to sue them for damages before a donor offered to cover the cleanup. One of the demonstrators, LGBTQ+ community leader Terry Tebedo, was seriously ill at the time and eventually died from AIDS. But Tebedo passed hot chocolate out to participants despite his poor health. “I can still taste it,” Monroe said sometime before his own AIDS-related death last year.

Things shifted after an arsonist razed the AIDS Resource Center in 1989, Waybourn says. Dallas’ gay and lesbian community realized they weren’t as safe as they thought they were. It didn’t happen overnight, but the blaze sparked a “huge awakening” for many. “That was the tipping point, where people realized that you can either sit on your hands or you can get involved,” Waybourn says. “And for a lot of people, it was to get involved.”

***

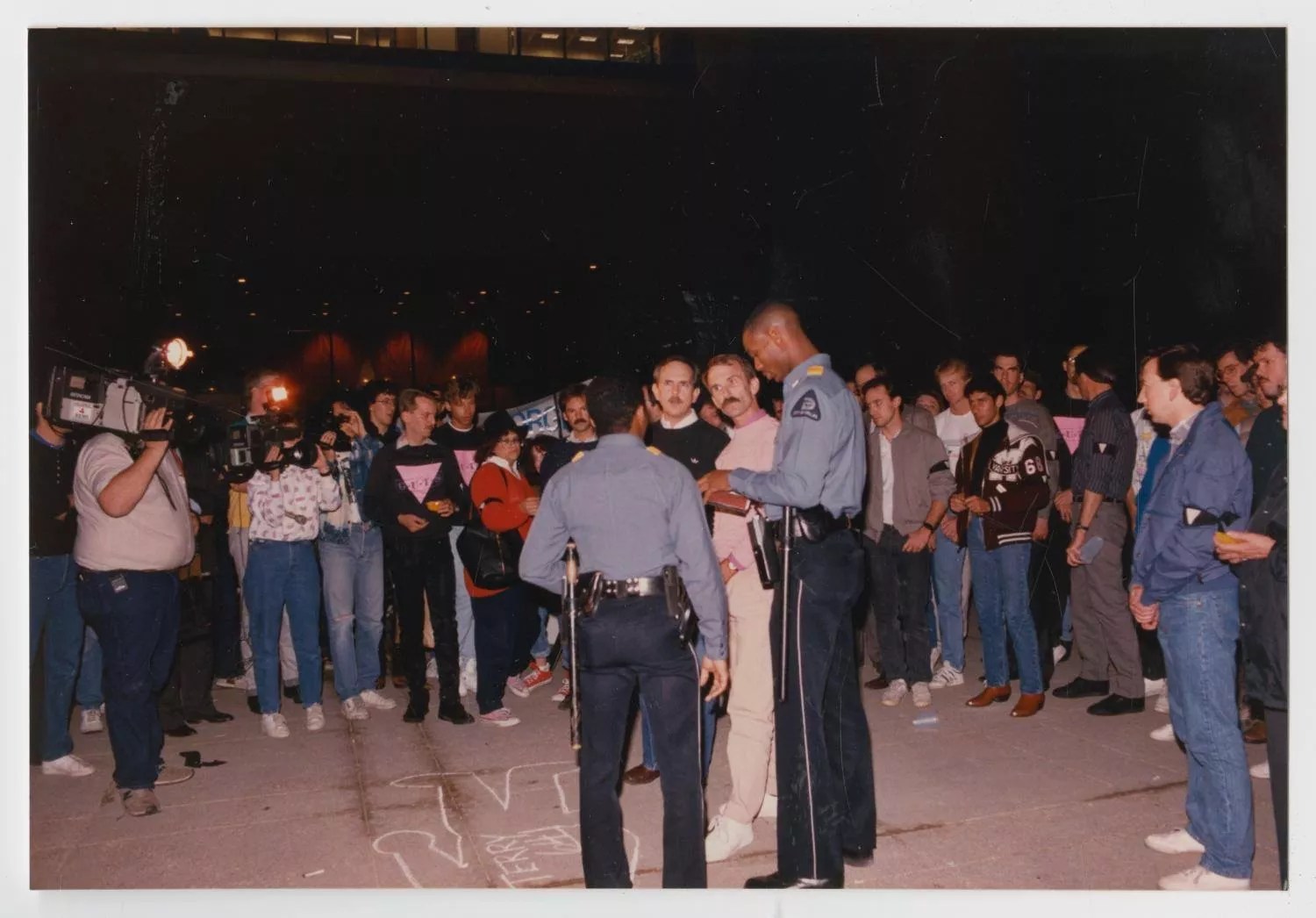

Christmas lights danced on posters demanding District Judge Jack Hampton’s ouster. “Hampton and Hitler Don’t Know Love,” one read. Protesters who’d gathered near City Hall roared: “Hampton must go!” At that point in late 1988, around 1,100 Dallas County residents had died of AIDS since the county started keeping track five years earlier. But days before Christmas that year, protesters with the Dallas Gay Alliance and other groups made it known that they were fed up with the unequal treatment they received under the law.

LGBTQ+ activists accused Hampton of making “anti-gay statements,” according to a Dallas Morning News article published in December that year. They believed he’d handed down a light punishment to an 18-year-old who fatally shot two gay men. Even though the law allowed for a life sentence, Hampton gave the convicted murderer 30 years. He reportedly justified the decision to a local journalist, saying the victims were “queers asking for trouble cruising the streets, picking up teenage boys.”

“Dallas bears the shame for every day [Hampton] sits there, and the world is watching,” said Waybourn, who served as Dallas Gay Alliance president, according to the News. “It is not the first time that gays and minorities have been brutalized and victimized by the Dallas County judicial system.”

Discrimination also wormed its way into the workforce. People would lose their jobs for being gay, Waybourn tells the Observer. Lone Star Gas fired male waiters assigned to the executive dining room for fear they would expose the bigwigs to AIDS. Servers were still allowed to work in the employee dining rooms, though, Waybourn says.

“You didn’t go to T-ball practice. You went to learn how to sink an IV.” – William Waybourn, GUTS

Republican President Ronald Reagan long avoided talking about AIDS, mentioning it for the first time publicly in September 1985, more than four years after taking office. (What would come to be called the AIDS epidemic was reported as early as June 1981. Later that summer, the public began referring to it as “gay cancer.”) The stigma surrounding AIDS made it difficult to find accurate information, and the county was limited in what it could say, so the Dallas Gay Alliance launched its own education program to teach people about how to stay safe. “Really, we were the only source of information that was reliable and truthful,” Waybourn says.

Some believed that the gay community had created AIDS via its “alternate lifestyle,” the University of North Texas’ library notes on its website. HIV- and AIDS-positive people were often shunned because of misguided fears about casual transmission. For a time, conspiracy theories spread that it could be contracted like the common cold.

Lyndon H. LaRouche Jr., an influential and frequent presidential candidate known for his homophobic and anti-Semitic views, speculated that the U.S. government had lied about the truth behind AIDS. “There is no known case, in which any research institution has conducted tests to determine whether AIDS is or is not actually transmitted by coughing, kissing, or insect-bites, for example,” he wrote in a 1987 Democratic campaign pamphlet. Fervent LaRouche followers once fought for political power in Dallas County. GUTS would stage protests to confront his supporters, counteracting propaganda with accurate AIDS information.

In 1981, one person reportedly died from the disease in Dallas County, according to a decades-old news package. The annual death toll ballooned from there: 78 in 1984 to an estimated 129 the following year.

Crossroads Market, Dallas’ de facto LGBTQ+ community center, had 12 partners when it first opened, Waybourn says. Only two remained by the time they sold it roughly a decade later in 1991: Waybourn and his boyfriend. Everyone else had died. Funerals were frequent. “Two a week, sometimes three a week,” Waybourn says. “And you didn’t go to T-ball practice. You went to learn how to sink an IV.”

Medicine left behind by the deceased was given to those in need.

Dallas Gay Alliance sued in the late 1980s with claims that Parkland Hospital had just one physician who managed more than 700 AIDS patients every month. The waiting list for treatment grew and grew. Seven people reportedly died before they could get care. Waybourn remembers that at the time, the Dallas Chamber of Commerce had invested heavily in a tourism promotion campaign. Yet the greatest resource someone with HIV could receive was a bus or plane ticket to a city with better services, he says.

Parkland now has neighborhood clinics all over the city, Waybourn says. Officials realized that it was better to put medicine where the people were. “There’s a lot more savings in wellness than there is in illness,” he says.

***

After years of demonstrating and correcting misinformation, Waybourn set his sights on public office. Ann Richards recognized that EMILY’s List, a political action committee supporting Democratic women, had helped her secure the Texas governor’s mansion in 1990. LGBTQ+ people needed something similar, Waybourn thought.

So he started the Victory Fund.

Waybourn drove to Washington, D.C., in April 1991 with his dog Pepper, a German shepherd and lab mix. His longtime partner, Craig Spaulding, headed that way months later, bringing along the couple’s two cats, Yuri and Buford Pussy. A basement office served as headquarters, which housed a cheap computer and printer, according to The Dallas Way. Soon, the Victory Fund began petitioning for donations. If they received $200, they’d give half to candidates and half to the fund. It led to the creation of a national mailing list featuring prominent people in the queer community.

Openly LGBTQ+ members were now running for office – like Craig McDaniel, who was elected to Dallas City Council in 1993.

But Waybourn never actually ran himself: “I’d make a terrible candidate,” he says, chuckling. Still, he wanted to launch the Victory Fund to make sure contenders would understand what they were getting into and how to respond to the day’s pressing issues. “People don’t care about who you’re sleeping with as much as they care whether or not the potholes are going to get fixed,” he says.

“You have to turn anger, fear and grief into action.” – Ricardo Martinez, Equality Texas

Dallas City Council has recognized June as Pride Month for years, and rainbow flags now fly outside City Hall, Fair Park and Dallas Love Field Airport. Earlier this month, council members unanimously voted to commemorate the late, legendary gay rights activist Don Maison with street toppers. Texas could also soon gain its first Black lawmaker living with HIV: Dallas-based Victory Fund endorsee Venton Jones will be the Democrat on ballot for House District 100 in November.

Mayor Pro Tem Chad West has earned the Victory Fund’s backing, too, and said it was meaningful because of the group’s thorough vetting process. Diversity makes communities and elected bodies stronger, he says, and it’s important for LGBTQ+ people to have representatives who can speak for them.

“The Victory Fund recognizes that,” West says, “and they help candidates who might not otherwise have a platform or … a strong support network to get started.”

***

The quilt panel was crafted from white cloth with hand-cut black letters and spelled out a grim message. “My name is Duane Kearns Puryear,” it read. “I was born on December 20, 1964. I was diagnosed with AIDS on September 7, 1987 at 4:45 PM. I was 22 years old. Sometimes, it makes me very sad. I made this panel myself. If you are reading it, I am dead …”

Puryear, who died in 1991, had been active as an organizer with GUTS and participated in the potter’s field demonstration, according to The Dallas Way. He aspired to be “the first person to make his own panel for the AIDS Quilt,” a grand memorial honoring AIDS victims. Today, the quilt has nearly 110,000 names stitched into some 50,000 panels, according to the National AIDS Memorial.

Equality Texas CEO Ricardo Martinez has read about the quilt and says when he was a teen, he was inspired by organizations like ACT UP. (Eventually, Waybourn says, ACT UP embraced GUTS and the group updated its name to GUTS: ACT UP.)

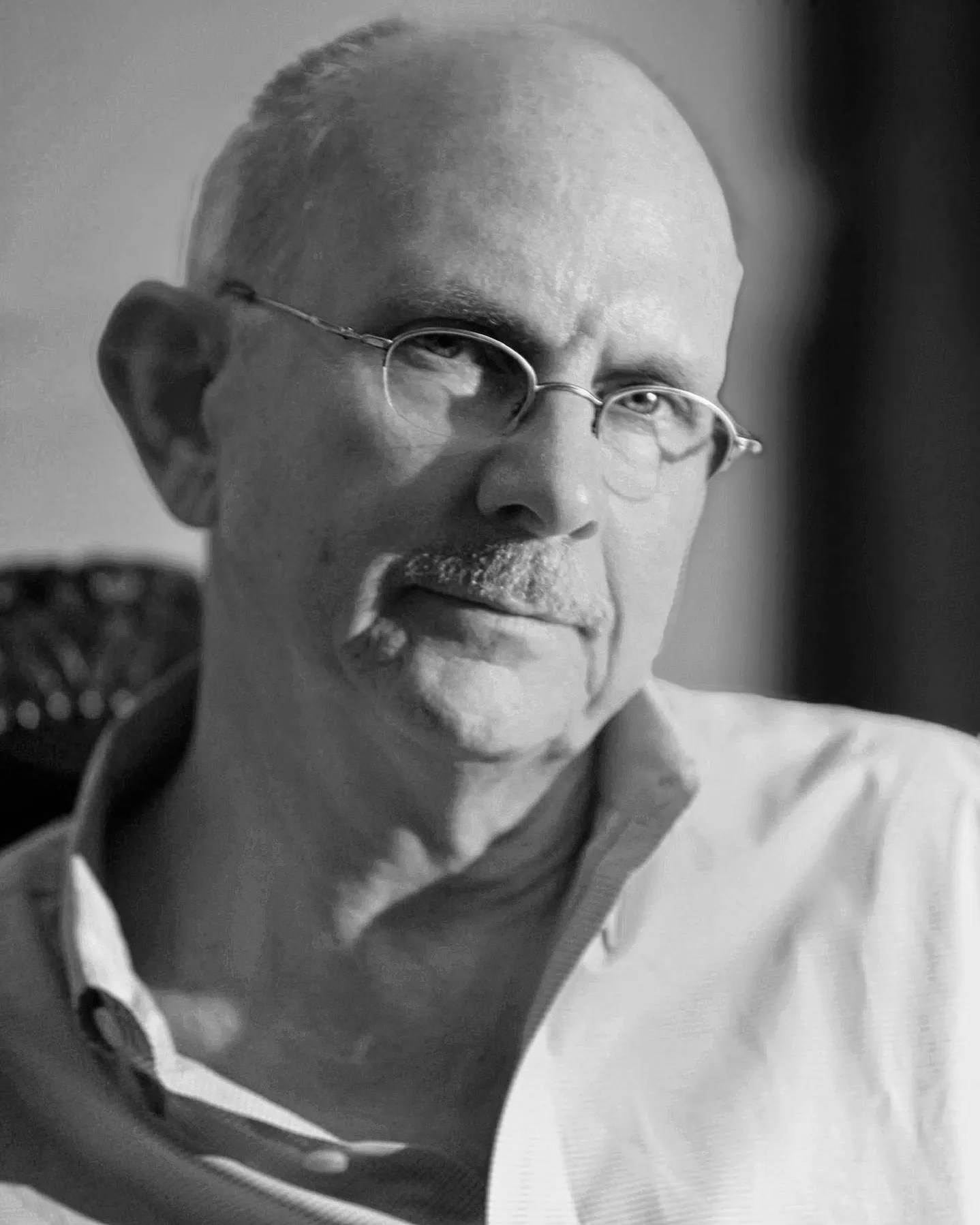

William Waybourn lead the Gay Urban Truth Squad (GUTS) in the late ’80s in Dallas.

courtesy William Waybourn

Even though the LGBTQ+ community has made progress over the past several decades, those gains need to be defended, Martinez says. Texas has turned increasingly combative toward gay and transgender rights during the past two years. Lawmakers have banned trans kids from playing on the sports team that aligns with their gender identity, and some want to outlaw family-friendly drag shows.

Martinez believes we’re living in a historic moment, and that many are feeling its heaviness. But people need to participate in whatever way they can, he says. They can’t just stay home and expect it to all work out.

Around 70% of Texans agree that discrimination against LGBTQ+ people is wrong, but they need to live out those values. “That means show up,” Martinez says. Referencing a famous ACT UP-affiliated quote, he adds, “You have to turn anger, fear and grief into action.”

Many advocates say Texas has turned back the clock on gay rights. Still, Waybourn is optimistic and thinks today’s kids are “going to see through this.” Children learn prejudice from their families or friends or churches or schools, he says. They aren’t born with it.

Earlier this year, Irving ISD school board trustees declined to renew MacArthur High School teacher Rachel Stonecipher’s contract. The North Texan had served as an adviser on the school’s Gay-Straight Alliance. She came under fire after putting rainbow stickers on her classroom door, indicating a safe space for LGBTQ+ students.

Prejudice is spreading in Texas and beyond, Waybourn says, but it’s not acceptable to simply roll over. Asked for his solution to mounting intolerance, Waybourn takes a beat and softly sighs. Then, he offers a succinct reply: “Act up and fight back.”