“The reason that’s important to me is I have some friends in the graveyard for the right to vote,” he says. “This didn’t come easy. This came with bloodshed and funerals. It took a long, long time. It was a very difficult fight.”

Johnson moved to Dallas after the death of Martin Luther King Jr. He was a young man on a mission to promote a documentary about King’s life and raise money for the slain civil rights leader’s family. But Dallas wasn’t having it, so Johnson stayed.

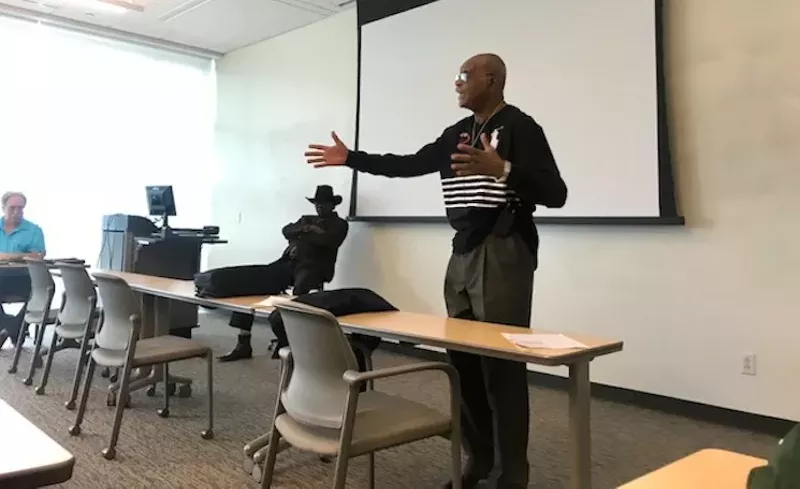

Now in his 70s, he has an adjunct position teaching a course titled The African American Civil Rights Movement 1954-1970, along with Walt Borges. The class explains the history of the movement as well as the philosophy and theology behind it, Johnson says. It also gives him the opportunity to talk about what he saw and how it affected him.

Some memories he still finds painful.

Johnson begins the class talking about Selma, in Dallas County, Alabama. He shares how King passed through Selma on his way to court Coretta Scott — but not without stern warnings from his elders to be extra careful.

Selma became part of the movement “because of hardheaded college students like yourself,” Johnson tells the class. “Students were the foot soldiers of the civil rights movement.”

Students had been in the area trying to help people overcome their fears of going to the courthouse so they could vote, Johnson says. Each student strove to get just five other people to join the protest.

“There were no emails, no computers, no cellphones,” he says. “I tell people it was all in God’s hands, but we were able to mobilize thousands of people based on the concept.”

As Johnson talks, his cousin, blues singer Ernie Johnson, listens. A brown western hat, pulled low, hides his face. Every now and then, he utters an “uh-huh” or “mmm," lending the class a gospel-like atmosphere.

Ernie Johnson recounts opening for BB King, buying gas for 10 cents a gallon and looking into the audience and seeing a young Stevie Ray Vaughan.

“You can pull me up. You can Google me,” he says. “I’m probably in the Bible by now.” Later, he autographed a student's CD.

“There were no emails, no computers, no cellphones. I tell people it was all in God’s hands, but we were able to mobilize thousands of people based on the concept.” – the Rev. Peter Johnson

tweet this

Peter Johnson continues with a story about one New Year’s Eve in Dallas when black people gathered in a Lutheran church and threatened a protest to block the city’s segregated Cotton Bowl Parade on national television if then-Mayor Erik Jonnson refused to meet with them. TV stations ran clips of people in the church preparing to block the parade. Johnson says the police instructed them to leave the church because of bomb threats.

“My position was, they can’t run them out of the church,” Johnson says. “But they could arrest them on national television for being in the church.”

The churchgoers weren’t arrested, and shortly before midnight, the mayor called to say he would talk.

“Now, we couldn’t have done that with guns," Johnson says.

Johnson didn’t talk with the mayor that night because he didn’t own a home in South Dallas; he says he thought it was important for the people to speak for themselves. But he recalls telling the group, "If they ain't no negros in that parade tomorrow, we still going to stop it.”

The next morning, Johnson watched the Cotton Bowl parade on a hotel room television in Shreveport, Louisiana, as a newscaster pointed out Dallas’ mayor and then said, “and I don’t know who that negro man is standing next to him.” Segregated parades had come to an end in Dallas.

Cynthia Pitts, a visitor in the class, shares that she was a child in Birmingham, Alabama, when her aunts came running into the house one day, saying, “They turned the hoses on us.”

Johnson pulls back a sleeve to reveal scars from dog bites. At times during the discussion, his voice takes on a hard edge. But when Johnson talks about music and his close friend Donald Byrd, his eyes are filled with happiness.

“Music ain't got no color,” Johnson says the jazz musician once told him. “It’s just music.”