Kiki Kita

Audio By Carbonatix

The year 1967 was a stellar one for movies. The marquees at movie theaters that year lit up with titles such as The Graduate, The Producers, In the Heat of the Night, Cool Hand Luke, In Cold Blood and Guess Who’s Coming to Dinner.

The year also saw the release of two major films made in Dallas. They were shot around the same time and hit theaters within just a couple of weeks of one another, and both laid the foundation of Dallas filmmaking. The first was Bonnie and Clyde, the Oscar-nominated drama from director Arthur Penn starring Warren Beatty and Faye Dunaway.

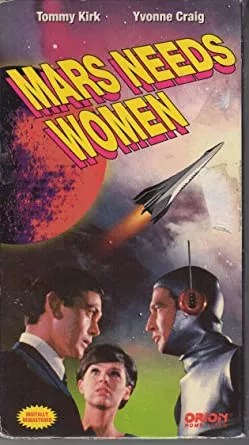

The other was Mars Needs Women, directed by self-described “schlockmeister” Larry Buchanan (who would’ve turned 100 years old on Jan. 31 if not for his death in 2004) and starring fallen Disney idol Tommy Kirk and TV’s Batgirl, Yvonne Craig, in a bizarre story about aliens kidnapping Earth’s most attractive women to restore their home planet’s dwindling population.

Buchanan’s model of cheap and fast moviemaking produced the kind of films seen on drive-in screens, introduced by Saturday night horror hosts on UHF-TV stations or screened on the Satellite of Love for Joel and the bots on Mystery Science Theater 3000. They cemented Buchanan’s legacy as a master of rubber-monster movies.

“You gotta have respect for anybody working with 35mm film or 16mm film and getting a film finished,” says Joe Bob Briggs, the famed drive-in movie critic of the Dallas Times Herald and host of Shudder’s late-night horror movie series The Last Drive-In. “It was the hardest thing in the world. Nothing like today where technically you can not only shoot a film with your iPhone but can also shoot a film with the stuff you can buy at Best Buy and make it look good. It’s a huge barrier of entry to the film business, and these guys broke down the barriers and actually got films released.”

Mars Needs Women was one of Buchanan’s most famous efforts.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan

Buchanan’s Azalea Films imprint, based in Dallas in the late 1960s, released a string of cheesy horror and sci-fi movies for American International Pictures (AIP) with titles such as Zontar: The Thing from Venus, Attack of the Eye Creatures, Curse of the Swamp Creature and It’s Alive!, which starred a fish humanoid with tennis balls for eyes and became his signature film. These are also some of the key productions that jumpstarted the Dallas film scene.

“I actually think that films like these and Lloyd Kaufman’s and Ed Wood’s and what they’ve done, filmmakers should be grateful for the work they’ve done,” says Tom Armer, the city of Dallas’ film commissioner and director of creative industries. “The inventors of indie filmmakers who went out on their own and made a film without a studio, they gave kids who wanted in the industry the hope that they didn’t have to live in Los Angeles or New York to make a film.”

It’s Alive!

Marcus Larry Seale Jr. – who’d change his name to Larry Buchanan when he became a contract player with 20th Century Fox – was born Jan. 31, 1923, in the East Texas town of Lost Prairie to Maude Dove Seale and Larry Seale, a peace officer and guitar player, respectively. His mother died from pneumonia when Buchanan was 9 months old, and not long after his father made the “gut-wrenching decision” to put Larry, his four sisters and brother in the Buckner Orphans Home in Dallas, according to Buchanan’s 1996 autobiography It Came from Hunger!

The strict discipline of the Baptist orphanage’s matrons took a mental toll on him, but Buchanan found solace in the weekly movie nights that inspired him to seek out his own film career.

He hitchhiked to Hollywood in 1942 after high school to pursue his passion, then moved to New York, where he found work as a model for magazine ads and in acting and music jobs. His Texan good looks and trusty Jumbo Martin Dreadnought guitar helped land him a role on NBC’s The Gabby Hayes Show.

“The beginning of my life in film,” he wrote, came when he landed a lucrative job with the Army Signal Corps making training films for the military at the behest of his TV costar, Rod Steiger. He had his first leading role on-screen as an aw-shucks hillbilly Army private in a training film called Homer Goes Hygienic.

The Army Signal Corps became Buchanan’s film school. He learned how to write, shoot, edit, act and even score movies. It’s where he also became friends with fellow aspiring filmmaker Stanley Kubrick, who had just shot his first short film, a boxing documentary called Day of the Fight.

Buchanan decided to move his career from performing to filmmaking. He wrote and shot a short Western in San Angelo called The Cowboy with his brother Earl using a 35mm military-grade camera. The Cowboy screened before the premiere of the film version of Arthur Miller’s Death of a Salesman at the Victoria Theater on Broadway in 1951 and ran for nine weeks. He continued to work on other productions including as an assistant director on the 1952 romantic comedy The Marrying Kind, starring Judy Holliday and Aldo Ray, where he met his wife Jane who worked as an extra.

Inspired by The Cowboy’s success, Buchanan wrote and shot his first feature-length film – a Western called Apache Gold (aka Grubstake) in 1952. He cast actor Jack Klugman as the film’s heavy; Klugman went on to find fame in some of the most memorable episodes of Rod Serling’s The Twilight Zone and as the sportswriter slob Oscar Madison on the sitcom adaptation of Neil Simon’s The Odd Couple. He returned to Texas to shoot the film on either side of the Rio Grande river, but the production ran out of money and the only screen time it saw was as stock footage for TV Western scenes.

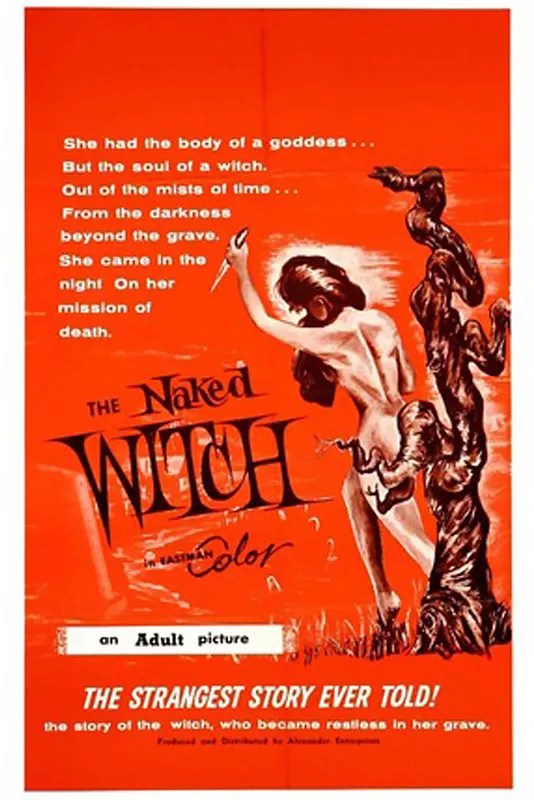

The Naked Witch made a name for Buchanan.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan

For two more years, Larry wrote and produced several off-Broadway productions and toured as an understudy and stage manager with the Broadway company for the Samuel and Bella Spewack comedy My Three Angels that would be remade in 1955 as We’re No Angels starring Humphrey Bogart, Peter Ustinov and Aldo Ray. Then in 1954, Jane gave birth to their first son, Barry. Becoming a father who vowed not to abandon his child like his father did, his priorities had to change. Not long after, he received an offer to run the commercial and documentary departments for the massive Jamieson Film Co. of Dallas.

“There are so many people who were touched by the [Jamieson] company including people who are still working actively in Dallas right now,” says Elizabeth Hansen, managing director of the Texas Archive of the Moving Image. “It’s really interesting how it’s this hub for filmmaking.”

Buchanan hesitated but eventually agreed to take the job if the company would let him make his own features.

“His understanding when Jamieson hired him is that he was gonna continue to pursue his feature film projects and they said, ‘That’s fine,'” says Jeff Buchanan, a writer and Larry’s second son, who spent a lot of time on his dad’s sets and helping on film projects. “They tried to bait him with, ‘Oh, we’ll make a movie’ and we never did, but that’s what brought him to Dallas.”

The Thing from Venus

Larry Buchanan started his Dallas indie film career with a soft-porn flick called Venus in Furs, a movie financed by a nameless, Rolls Royce-driving Texas oil baron for his busty girlfriend, which became “my first real experience in guerrilla cinema,” Buchanan wrote in his autobiography.

The success of other films such as The Naked Witch and Free, White and 21 spread the word that a professional filmmaker was in town who could turn an $8,000 investment into an $80,000 windfall. He started putting together a crew who could do everything a big-budget crew could do, but faster. “I couldn’t let them down,” Buchanan wrote.

“My dad very openly dreamed about building a film town out of Dallas, and all these people started coming on board,” Jeff Buchanan says. “‘We don’t need Hollywood, and we can do everything here.’ What he liked about it was the enthusiasm because in LA everyone is so jaded about films, but in Texas, people get excited.”

Buchanan’s films were a byproduct of a hearty appetite for cheaply made drive-in movies.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan

Inspired by the nightclub life he encountered in Dallas, including burlesque dancer and stag film star Candy Barr and the infamous Carousel Club owner Jack Ruby, Buchanan wrote and made A Stripper Is Born, better known as Naughty Dallas, in 1964.

Headlines about conspiracies and crimes inspired future productions such as 1964’s The Trial of Lee Harvey Oswald and 1984’s Down on Us, which examined how the deaths of rock ‘n’ roll legends such as Jimi Hendrix, Janis Joplin and Jim Morrison might have been murders orchestrated by the government. He was the first to turn the life story of Marilyn Monroe into a film with 1976’s Goodbye, Norma Jean.

“He was one of the great headline moviemakers where he takes whatever’s the latest headline and does the movie version of it,” Briggs says. “Obviously, a man of his time.”

Buchanan’s films caught the attention of AIP founders James Nicholson and Samuel Arkoff. They struck a deal to make sci-fi and horror films for television and the drive-in circuit starting in 1967 with Attack of the Eye Creatures, a remake of Ed Cahn’s Invasion of the Saucer Men. These and a string of future films like Zontar: The Things From Venus, Curse of the Swamp Creature and It’s Alive! would become part of Buchanan’s iconic “Azalea Collection” named for his Dallas film studio.

“They used to just have these jam sessions at AIP in the morning and it was Arkoff, my dad, Roger Corman, Jim Nicholson and they would just have sessions and throw out titles and that’s what they’re gonna produce,” Jeff Buchanan says. “My dad told Sam, he just called him and said ‘Mars needs women.’ This was on a Friday morning. Sam said, ‘That’s great. Is that what I think it is?’ He said yes and Sam said, ‘Can you have it over by Monday morning?'”

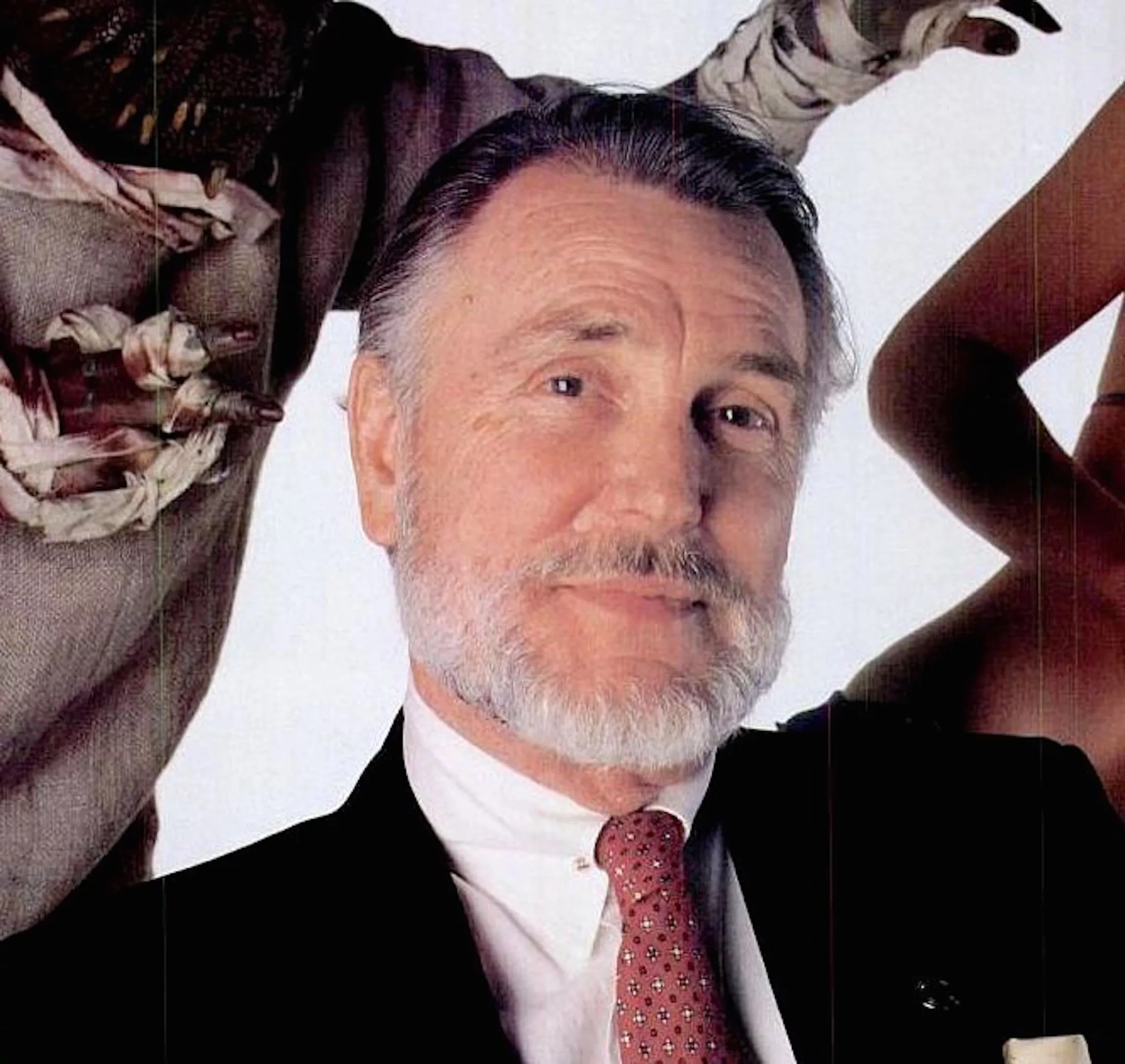

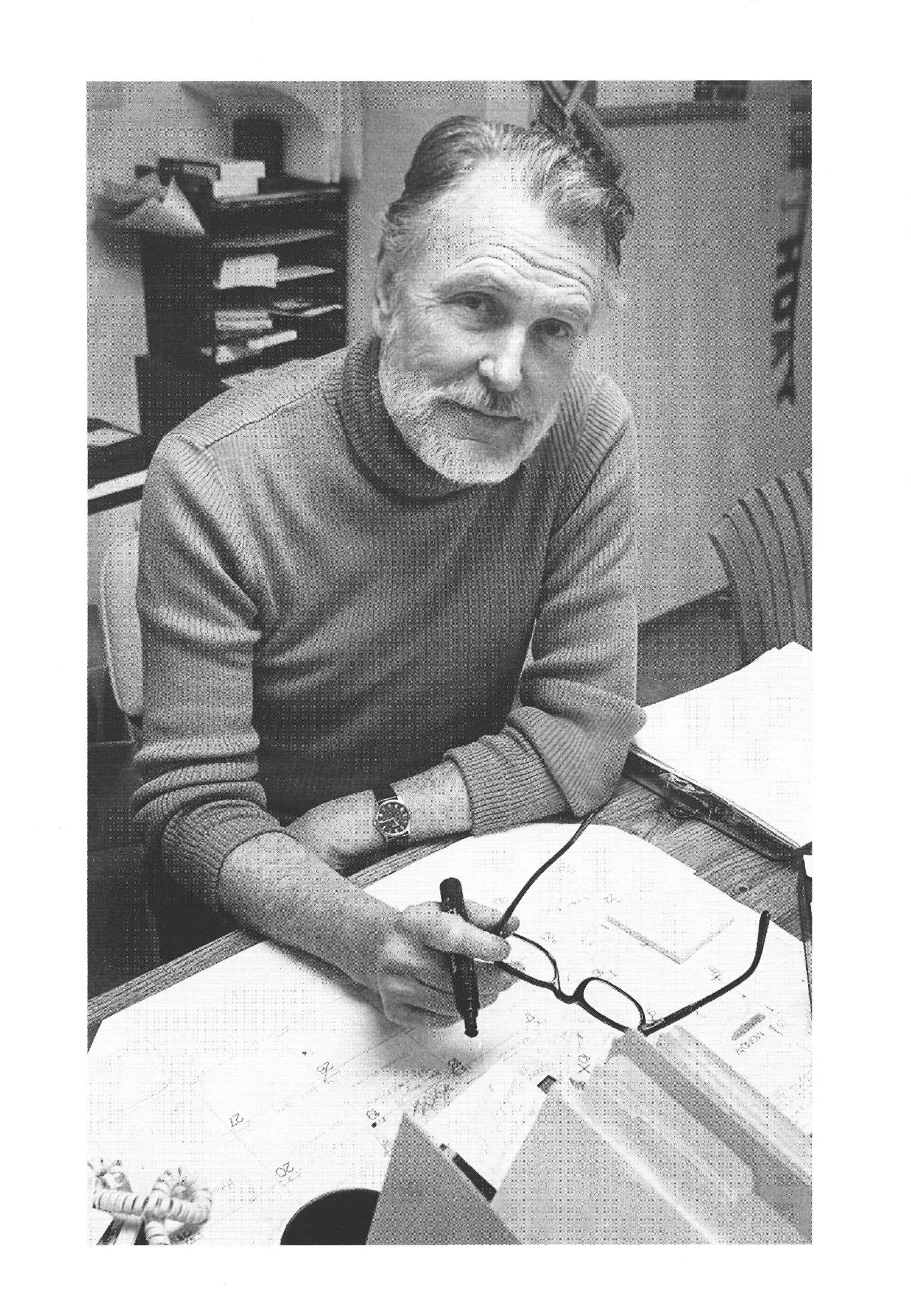

Larry Buchanan in the 1980s.

courtesy Jeff Buchanan

Creature of Destruction

Buchanan achieved what he wanted with his AIP deal. He had a steady stream of projects for his crew and a small film empire in Dallas, but his drive to create pushed him to do more than just recycle familiar film plots.

“I had reached my pain threshold in the remaking of bad scripts, and I told the heads of AIP that, as a breather, I wanted to do my own script, Mars Needs Women,” Buchanan wrote. “Had they balked, I would have walked … but they loved the script.”

Arkoff’s only condition was that he put actor Tommy Kirk in the picture, which Buchanan did with a role as an alien named Dop. Kirk had found fame as a child actor in Walt Disney Pictures hits such as Old Yeller, The Absent Minded Professor and Swiss Family Robinson until Disney fired him after learning that Kirk was gay and was seeing a 15-year-old boy while Kirk was 21. Buchanan also cast Yvonne Craig as his sexy leading scientist, Dr. Marjorie Bolen. Craig, who attended high school in Dallas, would go on to play Barbara Gordon, aka Batgirl, on ABC’s Batman.

Kirk “would be a draw to at least bring an audience,” says Dallas film producer Don Stokes, whose father worked alongside Buchanan at Jamieson and spent lots of time on both of their film sets when he was a kid. “So the people who loved him with the Disney audience, those are people who would be willing to forgive him in this other thing. Then, fill it with other actors who are competent and good and maybe not as recognizable.”

Mars Needs Women was filmed entirely in Dallas and included scenes of the White Rock pump station and the planetarium in Fair Park standing in for “Houston.” It would become Buchanan’s most recognizable film.

“It’s relatively speaking the most polished of those,” says Gordon K. Smith, a Dallas film historian, teacher and writer for the Turner Classic Movies channel. “It’s sort of in big quotes a ‘sequel’ to Pajama Party, in which Tommy Kirk played a Martian with a different name. It’s probably the most widely seen of those.”

It became one of the featured films in the 1982 comedy documentary It Came from Hollywood, mocked by Dan Aykroyd, Gilda Radner and Cheech and Chong alongside the works of Ed Wood and the Danish monster epic Reptilicus. The musical group MARRS sampled a vocal track of the film for the 1987 house music hit “Pump Up the Volume.” It’s been referenced in songs by Frank Zappa, Rob Zombie and The Chemical Brothers. It’s been optioned for big budget remakes, a sequel and even as a Broadway musical.

“Larry knew what he was doing, but he wasn’t ashamed of what he was doing,” Stokes says. “He was proud.”

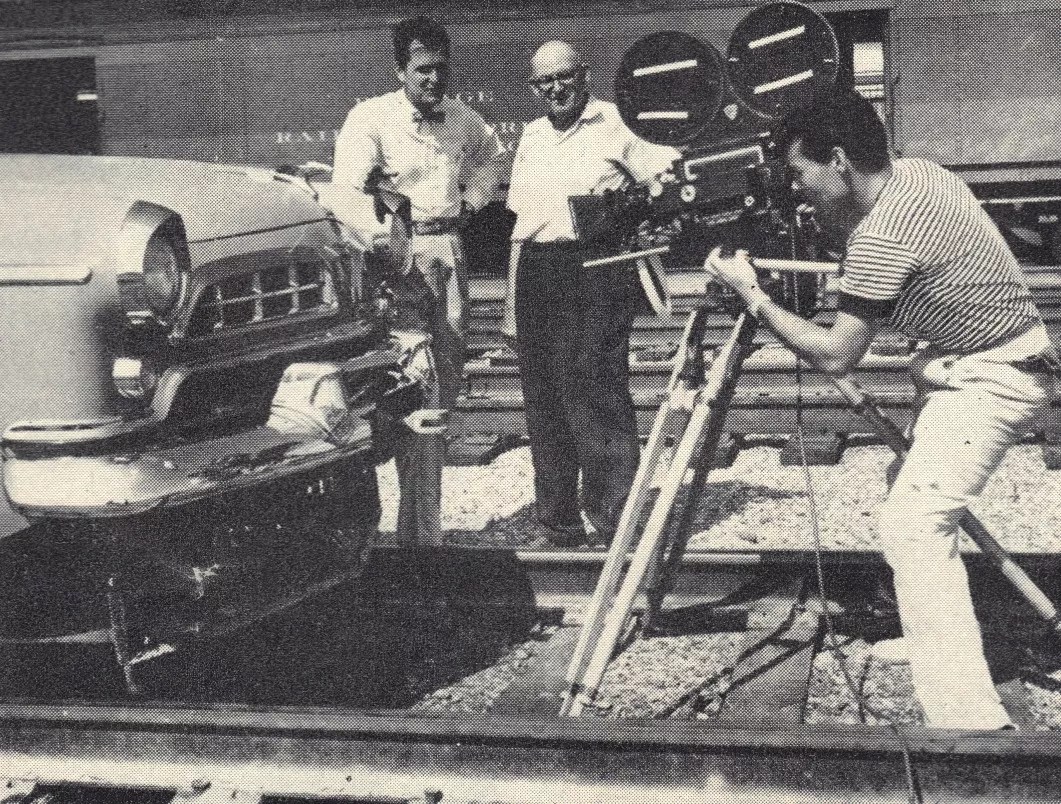

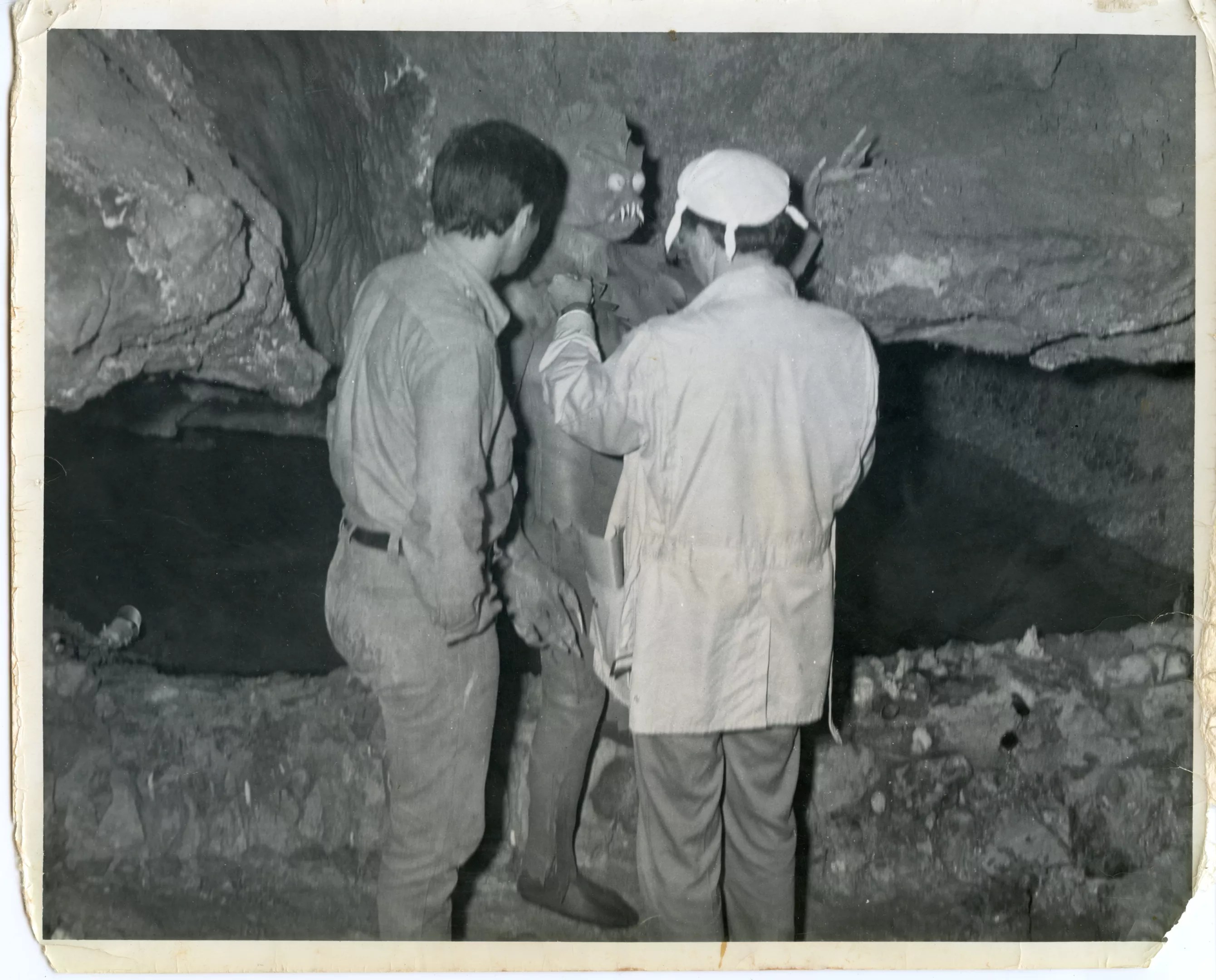

Director Buchanan at work on a close-up shot.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan

Larry Buchanan had low budgets, fast timelines and few special effects to make his movie monsters come to life.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan

Down on Us

Buchanan continued to make movies throughout the ’70s, ’80s and ’90s, but the movies of his Azalea period like Mars Needs Women followed him. Jeff Buchanan says he relished every review of every movie, good or bad.

“The case in point is Goodbye, Norma Jean,” Jeff says. “When that came out, it made Playboy‘s top 10 worst films of the year. I said, ‘Dad, doesn’t this bother you?’ He said, ‘Look at the other films. If Playboy knew how little money we made this for, they would’ve been embarrassed for putting it on here.'”

He tried to shake his reputation as a B-movie monster maker after the 1969 release of It’s Alive!, a project Buchanan called “all anguish and no fun.” He pursued weightier projects like the crime drama A Bullet for Pretty Boy and 1971’s Strawberries Need Rain, an Ingmar Bergman-inspired tale about a young woman who makes a deal with death for one more day of sexual exploration – which some theatergoers mistook for Bergman’s work.

They all made money, just like the projects he produced fast and cheap with rubber monster suits and minimalist space suits, but the images of those movies followed him into every pitch meeting.

“I wanted to redeem my father and produce something where he could direct a small masterpiece,” Jeff Buchanan says. “We were working on a script I still very much love called Hurry Sundown. It’s like American Graffiti, but it’s the last night of a drive-in theater before it falls to the wrecking ball and they have an all-night marathon of Larry Buchanan films. For all the crap he put out there, he was a very sensitive man, highly intelligent, had a phenomenal understanding of the history of film and always hoped to do important films and had a couple of scripts and tried to get them going, but his reputation always preceded him in every meeting.

“This is the guy who makes the schlock. He never got to redeem himself.”

Buchanan’s reputation isn’t just what shows up on the screen at midnight movie marathons around the world or on the TV screens of beered-up movie nerds who think they’re Tom Servo mocking what they see from the comfort of their couch. It’s reflected in the crews who work on big-budget commercial, TV and film projects, because Buchanan gave some of them their first to work in Dallas, whether it was playing a fish monster, working on set as a grip or, in many cases, both.

“They used Larry’s movies as a stepping stone to bigger projects, and I think that’s a testament to Larry who provided those stepping stones,” Stokes says. “I’m sure he wasn’t thinking in those terms. It was a moment that helped a lot of people do what they wanted to do and what they wanted to achieve later in their lives.”

In his autobiography, Larry Buchanan described his life from the orphanage to Hollywood to New York.

Courtesy of Jeff Buchanan