National Archives / Handout- Getty

Audio By Carbonatix

Editor’s note: Dallas writer Bill Sanderson was 12 years old when he and two friends were freed from school and allowed to come to downtown Dallas to view President John F. Kennedy’s motorcade as he traveled to give a luncheon speech to Democratic supporters. While the boys watched the motorcade pass and then headed off to catch a movie, Sanderson’s mother, the late Eula Mae Sanderson, her husband, J.W., and best friends Don and Betty Ragsdale waited at the Trade Mart for a speech that would never be given.

Pulling from his mother’s journal and recollections from Betty Ragsdale and his friends Robert Strange and Darrell Dixon, Sanderson has stitched together this personal account of the day in Dallas 60 years ago that an assassin’s bullet ended Kennedy’s life and changed U.S. politics forever.

On Nov. 22, 1963, I was just a kid and didn’t know that Dallas was ground zero for political extremism. “Nut country,” JFK groused to his wife, Jackie, that morning after seeing the slur in a black-bordered full-page ad in The Dallas Morning News (according to William Manchester’s book Death of a President). I only knew that my buddies Darrell and Robert and I had our parents’ blessing to ride the bus downtown to see the president and afterward go to the Majestic Theatre for McClintock, starring John Wayne.

Government overthrow via assassination had played out a year earlier in the film The Manchurian Candidate. My friends and I joked about someone trying to kill JFK while we waited for his motorcade on Main Street. This was only a few minutes before he was slain on Elm and always added an eerie personal dimension to the historic crime.

Suddenly, a square-shouldered CIA type loomed before us on the sidewalk. He had unusual sunglasses and an ultra-thin attaché case concealing, we were sure, his collapsible sniper rifle, like the kind James Bond employed in the novel On Her Majesty’s Secret Service. Lacking only a belted raincoat, the guy exuded intrigue.

We elbowed each other in the ribs and cast knowing looks, goofing on the idea that he might be a Russian agent here to do a deadly job.

My friend Darrell, who claimed authorship of the unthinkable notion, doesn’t remember it as so carefree.

“Where did that fleeting dark thought come?” he recalls. “I’d never been close to a president and maybe, who knows, maybe Abraham Lincoln popped into my mind. I guess it was the darkest thought that you could think of at the time and I gave voice to it, and it’s kind of haunting now that you look back at it. And it added to some confusion later in the day.”

While we were downtown, my parents, J.W. and Eula Mae Sanderson, and their lifelong Democrat pals Don and Betty Ragsdale waited at the Trade Mart, just two miles up Stemmons Freeway.

Dallas had never hosted such an event, and 2,000 Democrats, more conservatives than liberals – the Gov. John Connally and U.S. Sen. Ralph Yarborough camps – showed up to see the charismatic president and his glamorous wife. Tremors of excitement seemed to shake the city, and had for days.

Tickets were a hot item. Manchester’s book notes that U.S. Attorney Barefoot Sanders “had been up early, distributing the last 25 luncheon tickets allotted to Dallas Democrats. At this hour they would have to be delivered by messenger, and some would not arrive until noon. Their elated recipients would be on the streets, fighting their way through the traffic around the Trade Mart as the motorcade reached its climax.”

My father snagged a last-minute ticket for Betty Ragsdale via Eugene Locke, a civic leader/lawyer who would later become ambassador to Pakistan and South Vietnam.

“We were thrilled to be going. I never dreamed I’d get to go. It’s the best thing that ever happened to me – absolutely,” Ragsdale remembers.

In her journal, my mother wrote: “None of the four of us had ever been so lighthearted. Here we had been good friends for the past 14 years, and this was something we were all doing that we’d never dreamed of. I shall never forget how beautiful the Trade Mart looked. Yellow roses everywhere – beautiful bouquets on all the tables, along with flags, Texas’ six flags.

“As we went into the Trade Mart, we were checked out by security and had to show our identification about every 6 feet. We were to sit on the second-floor balcony, sort of to the left and looking down at the table where the president would come. Betty had a tremendous seat – she was sitting with the Locke delegation.”

Ragsdale was excited about her seat. “They (J.W., Eula Mae and Don) could have just died. They thought it was the coolest thing that I got to be the one in the crown seat. I got to sit with Barefoot Sanders, that old red-hair. We had quite a conversation. I thought I was queen for a day.”

Ragsdale was easily the greatest JFK fan of the group of friends.

“The women loved him,” she recalls. “He had charisma. I think the women probably got him elected – I really do. I was crazy about the president, but when I told Don who I was going to vote for, I thought he was going to have a cow.”

The men of the group of friends that day were not smitten by the Kennedy magic and had supported Lyndon Johnson’s bid for the presidential nomination at the 1960 Democratic Convention.

My dad, a diehard Democrat with conservative stripes that faded later in life, refused to say who he voted for in the 1960 general election and took the secret of his choice to his grave.

Darrell Dixon’s dad was a Teamsters Union official, serving both as president of the Texas Conference of Teamsters and secretary/treasurer of the Southern Conference of Teamsters.

“I can’t say he liked Kennedy, because of the conflict with Jimmy Hoffa,” Darrell says of his father. “Attorney General Robert Kennedy was investigating corruption in the Teamsters Union, and as a result of those investigations the teamsters, instead of being supporters of Kennedy for president that year, they turned and supported Richard Nixon.”

As the adults settled in to await the president’s arrival, it happened.

“I saw all of these photographers running,” Betty Ragsdale remembers. “We sat and we waited and we waited, and then finally Sanders said to me, ‘The president’s been shot.’ We knew it at the table before they made the announcement. That’s something that’s burned in you, and you will never, never forget it.”

Earlier on Main Street, my friends and I were hugely enjoying the bright day and sidewalk diplomatic immunity from attending seventh-grade classes at San Jacinto Elementary School. I had squeezed to the front near the curb and to my everlasting good fortune locked eyes with the first lady. That moment so riveted me that I don’t remember seeing anyone else in the motorcade. It was over in a breath, then the limousines continued on at 10 mph, heading to the dogleg turn at Houston and back to Elm, in the shadow of the Texas School Book Depository.

My friends and I disagree on several details occurring that day, but not on the exotic beauty of Jackie Kennedy.

“My first sighting was of Jackie Kennedy’s pink hat, Darrell Dixon says. “I was mesmerized by how attractive she was – she looked like a movie star.”

About 12:30 p.m. we ambled a short block to the Majestic Theatre on Elm Street. I heard wailing sirens just as we entered the theater, which reminded me of a promise to call home and leave word that all was well.

Our family housekeeper Bertha Roberts broke the news. “Governor Connally got shot, and they shot the president, too.” It wasn’t possible, I told her. A minute ago I had waved at them. “I just saw it on TV,” she said.

Unbelievable as her story was, there could be no argument with the truth of TV. And you could count on Bertha not to exaggerate and not to lie under pain of death. Armed with the truth, I flew down the aisle, but Darrell and Robert just couldn’t swallow a story that our imaginations had concocted only minutes before.

“My reaction at the time was, ‘Come on, quit kidding around.'” Darrell says. “And this goes back to the dark moment I had about how horrible it would be if the president was assassinated in Dallas.”

The movie was beginning, and I was making a bit of a scene. My friends told me to sit down and shut up, and I said I would not unless they admitted that they believed me. We struck a grudging agreement, and I got quiet, but I knew they didn’t accept the unbelievable truth. There I sat, bewildered and alone somehow, in the sheltering darkness of the movie house.

Burdened by a reality that no one around me knew about or acknowledged, I thought that the Duke was a colossal fake in this movie. Standing atop the mudslide in what would become a famed cinematic brawl, John Wayne’s cowboy character, George Washington McClintock, says, “Somebody oughta belt you right in the mouth … but I won’t … I won’t … the hell I won’t,” and he wheels, swinging from the floor with a haymaker of a punch. We all saw it coming; not only did he telegraph his punch, he telegraphed his line. And all of his macho bluster then in this suspension of time seemed bogus.

Not much of the U.S. would be in the dark about the assassination for long. Manchester called it the greatest simultaneous experience that any nation ever shared. By 1 p.m. Dallas time, he wrote, 68% of all adults in the U.S. – more than 75 million people – knew of the shooting. The people in this movie and at the Trade Mart were among the last to learn.

At the Trade Mart, Betty Ragsdale was the first among her friends to get the news. “I thought, I’ve got to get to J.W. and Eula Mae. They were a couple of tiers up from me and I got up there and couldn’t hardly talk, saying, ‘You’re not going to believe it.'”

In her journal, my mother wrote: “My thoughts were, ‘Why doesn’t she tell me, why doesn’t she speak what she has to say?’ And then she said: ‘Somebody who is in the law firm with Mr. Locke came to the table and told his mother-in-law that the president and Gov. Connally had BOTH BEEN SHOT! And he said that there might be a conspiracy to overthrow the government and they were leaving.’

“Perhaps five or 10 minutes from the time that Betty told us, Erik Jonsson, a civic leader and later the mayor of Dallas, came to the mic and said, “‘Ladies and gentlemen, we have just received word that the president and Governor Connally have been shot. We don’t know to what extent they have been hurt.’

“Then he called on Luther Holcomb, president of the alliance of churches, to lead in prayer. I shall never forget the feeling – the simply profound feeling of deep prayer that 2,000 people joined in to. The complete reverence was so evident.

“Looking down from our balcony, you could see disbelief and grief on everybody. I remember seeing great big colored waiters crying, some even sobbing. Then in another five minutes they reported again that they thought Gov. Connally would live but he was in much pain, and they were giving the president blood.

“Later it was announced that the president was dead. Stunned, crying, incredulous people filed out of the Trade Mart. Policemen were huddled together. One of them told us that a policeman was DOA in Oak Cliff. He thought it had nothing to do with the president. We later found out it did.”

Back at the the Majestic Theatre, the manager walked onstage and said slowly and matter-of-factly: “I don’t know if any of you have heard or not (long pause), but President Kennedy has been shot, and he is dead.” No gasps or moans, just a gathering of whispers that grew to a great hissing sound that eclipsed all sensory memories of my life. A voice from the crowd asked something, and the manager answered, “Yes, Governor Connally has been shot. Don’t know if he’s dead.”

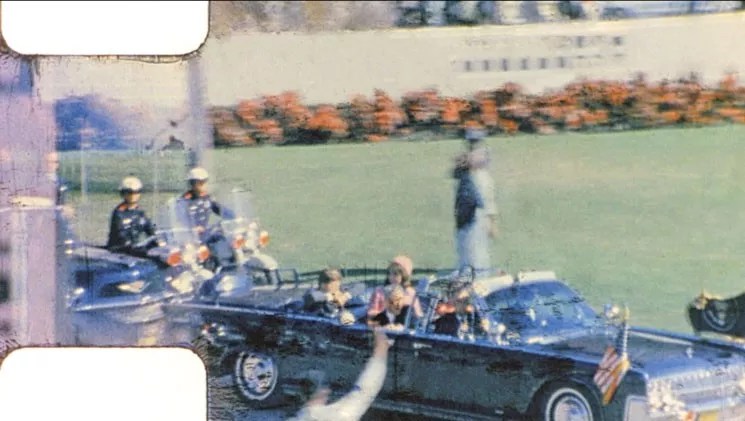

In an image from the Zapruder film, President Kennedy reacts to being struck by an assassin’s bullet.

Zapruder Film © 1967 (Renewed 1995) The Sixth Floor Museum at Dealey Plaza

“John Kennedy was kind of my hero because I had something personal to do with it when I pulled the lever that voted for him in 1960,” my friend Robert Strange remembers.

His mother had insisted he come to vote with her and enter the voting booth.

“Mother said, ‘Now Robert, who would you vote for?’ I said John Fitzgerald Kennedy, and she told me to reach up and pull the lever for JFK,” Robert remembers. “I had pulled the lever when he got elected and I felt the magic of Camelot, felt that something really good had happened and got to be a part of it.”

Later on TV, I watched Walter Cronkite when he broke up. I knew that something died that would have been great for America. It was gone and a feeling hit me hard that evil does exist, and I remember thinking about that. I have a hard time not getting emotional every time I talk about this.

So the malevolent fears of the early ’60s – the Cuban missile crisis, the instructions for lining your home’s hallway with phonebooks to insulate against radiation, the muted turmoil of meanness and bigotry – had all become flesh in a twinkling. Sorry and sad. And we didn’t grasp how sad that day; more it felt like slow-motion chaos, with little to be done or said.

I’m not sure we ever got over it in Dallas. Five years later, I was a teenager attending the International Key Club convention in Montreal, Canada, and a glib conventioneer, noting my hometown badge, cracked: “Are there any national historic landmarks in Dallas – other than the Texas School Book Depository?”

The murder had bumped Ford’s Theater, where Abraham Lincoln was slain, down to second place as the building thug of history. The National Parks Service declared the Dealey Plaza Historic District, which includes the building with its Dallas County offices and the Sixth Floor Museum, a national historic site in 1993. Now the Texas School Book Depository is neither joke nor insult, but the seven-story bookmark of a nation’s memory that will forever hold its stories – and its secrets.

Back row: J.W. Sanderson, holding his daughter Sally, and Eula Mae Sanderson. Front row: Bill Sanderson, Patti Gibbs and Dennis Geddie.

Courtesy of Bill Sanderson