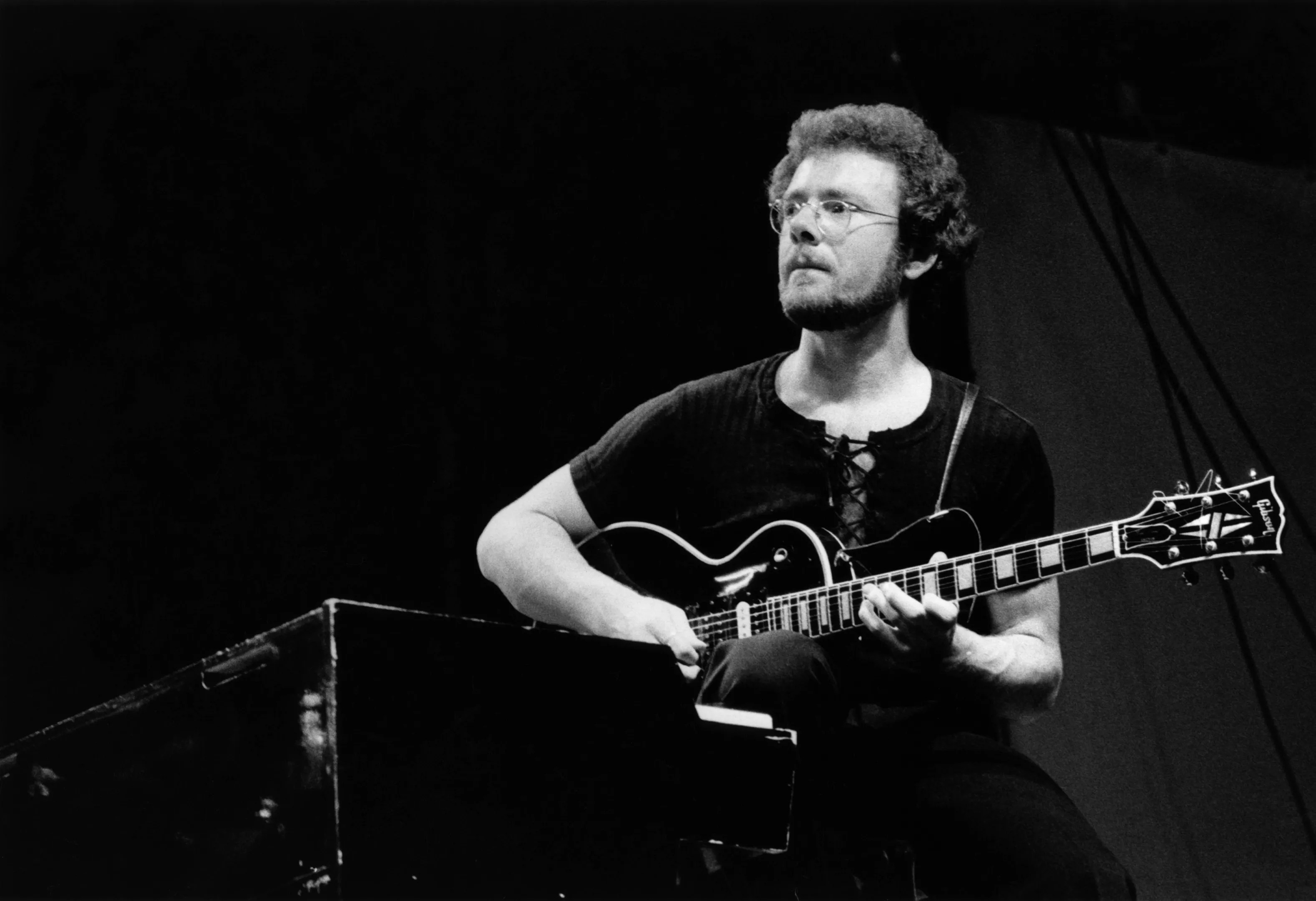

David Redfern/Getty

Audio By Carbonatix

What is a perfect band? Is it one like The Beatles, whose universal influence is nearly matched by their timeless popularity and maintained by their four distinct, iconic and deified personas? Is it one like AC/DC, whose carnally dependable brand of rock ‘n’ roll is so perfectly appealing to people of all ages that the band will be damned if they alter their formula by even one iota between albums? Or is it a band that has spent more than 50 years actively avoiding any semblance of sonic similarity, consistent membership, audience expectation or commercial success of any kind whatsoever?

For a good while, artists have championed the idea that playing by one’s own rules, living outside the expectations of others and simply existing as a vessel for the creative intersection of personal expression and intellectual exploration are the pillars of being an artist. So, by this definition, is King Crimson the perfect band?

King Crimson, which just announced a July 30 stop at the Will Rogers Memorial Auditorium in Fort Worth, has played in North Texas only twice in the last 40 years (by comparison, the group has played Buffalo six times in the same amount of time).

To those who skirt the third circle of music exploration (usually encountered after you’ve discovered Pink Floyd has more than four albums worth listening to), King Crimson remains a dragon in a mountain sitting atop a pile of gold, a dark secret in a locked room. Only those with the most formidable souls can unlock the door or access the riches without waking the beast.

A common descriptor of the band is: “No two of their albums sound the same.” That’s true, but it can also be said of Dire Straits, Kings of Leon or Sparks. It’s not difficult to carve out an identity for each set of songs birthed, but it is an accomplishment to make each album so radically different from the one that precedes it that you guarantee at least one listener will ask themselves whether they bought the right album.

Crimson is a band whose sole identity is change and whose relatives are variation, attrition, subversion, surprise and shock. Thirty seconds into their 1969 debut album In The Court of The Crimson King, the listener is startled by an assault on the senses: a previously unthinkable fusion of slippery jazz and blistering metal (especially surprising considering “metal” technically hadn’t been invented yet – Black Sabbath’s debut was still four months away). Seven minutes later, pastoral flutes lull listeners back to their senses, like the warmth of the morning sun caressing your face after you wake from a nightmare. And that’s just the first two songs.

King Crimson’s compulsion for spontaneity can be directly attributed to their very own crimson king: lead guitarist and sole constant member Robert Fripp, whose totalitarian grasp on the band is responsible for its attrition and attention to detail. From day one, the ethos he imposed on the band was a variation of “if it sounds like something that already exists, we can’t sound like that.”

After their second album was a little too stylistically similar to their first, Fripp started cracking skulls. Drummer Bill Bruford, who defected to King Crimson in 1973 from fellow prog rockers Yes, called King Crimson “a terrifying place” and described Fripp’s demands from him as follows: “Whatever you do before you join King Crimson, please don’t do it while you’re in the band.” Despite the pressure, or perhaps because of it, Bruford remained the band’s drummer for more than 25 years, between 1972 and 1997.

By no means has the brotherhood of Crim been a stable or loving one. In their 50-plus years of existence, King Crimson has gone through six lead singers, seven bass players, eight drummers (with three drummers in the band at this moment), three guitarists, two saxophonists, a violinist and a percussionist whose arsenal included a trash can lid and later left the band to become a Buddhist monk.

There is no “definitive” or “classic” lineup of King Crimson like there is for, say, Fleetwood Mac. In fact, King Crimson never made two albums back-to-back with the same lineup until 11 years into their career.

Many members couldn’t handle Fripp’s authoritarian regime and fled for sunnier (and more lucrative) pastures. This includes the band’s entire original lineup minus Fripp: founding vocalist/bassist Greg Lake quit midway through the recording of the band’s sophomore album to find immense success as a part of the chart-topping but critically reviled Emerson, Lake and Palmer; founding saxophonist/keyboardist Ian MacDonald quit King Crimson to start Foreigner; and founding drummer Michael Giles later found a steady income backing disco stalwart Leo Sayer.

In some ways, King Crimson was a proving ground for musicians to show off their chops and ability to work under pressure, and even then, KC alums aren’t always virtuosos of the art world. Late vocalist/bassist John Wetton eventually found himself (in ’82) on MTV as the voice of supergroup Asia (anyone who’s seen The 40-Year Old Virgin can dig that) and the band’s current drummer (one of the three) is none other than Pat Mastoletto, who first made a name for himself as the drummer for ’80s schlock-rockers Mr. Mister – yes, “Broken Wings” Mr. Mister.

Now that band is planning a return to North Texas – and at the risk of incurring the wrath of every King Crimson enthusiast with internet access – here are 10 King Crimson songs to get acquainted with the band

Literally every song from In The Court of The Crimson King

Any album that Pete Townshend calls “an uncanny masterpiece” and Robert Christgau calls “ersatz shit” is worth checking out. Considered by many music scholars as the first true “progressive rock” album, every musical quality that slapped the psychedelia out of people’s heads in the ’60s and led the way to the turbulent ’70s is on full display on the five songs that make up King Crimson’s 1969 debut. Not to mention, “Moonchild” will make Christina Ricci’s tapdancing scene in Buffalo ’66 much cooler. Man, what is it with Buffalo and King Crimson?

“Cadance and Cascade” from In the Wake of Poseidon

Greg Lake was gone, and in his place was a student of R&B named Gordon Haskell. Take a composition meant for Lake’s folksy croon and give it to a blue-eyed soul singer who had more in common with Van Morrison than The Moody Blues and you get possibly King Crimson’s single most accessible song. Bonus points if you can learn it solo and acoustic; you’ll reap many rewards around campfires if you can pull it off.

“Sailor’s Tale” from Islands

For an album emblazoned with an exploding nebula, Islands is very much a seafaring album. Its opener and closer both evoke the tranquility at the point where earth meets the sea, wherein between, seas are rough. The second track on the album, “Sailors Tale,” is as turbulent as high seas can be, with massive swells of Boz Burell’s bass and rogue waves of Mel Collins’ sax threatening to throw even the most skilled of listeners overboard. Somehow, though, that thrill of danger is what keeps them hanging on.

“Islands” from Islands

On the closing title track on King Crimson’s fourth album, an island is depicted as a place of loneliness just as much as it is an extension of the self. The final contribution to King Crimson by lyricist Pete Sinfield, the song spends every moment of its nine minutes hesitating as to whether the future is out at sea or Earthbound. King Crimson’s only piano ballad, “Islands” is not only a highpoint in the band’s discography, it is undoubtedly one of the most underrated songs in the 20th century rock canon. “Touch my island, touch me.”

“Larks Tongues in Aspic, Pt 1.” from Larks Tongues in Aspic

This is the King Crimson people warned you about. A radical collision of extraordinarily precise orchestral rock with the atonal rhythms of Tibetan gamelan music results in this, King Crimson’s most challenging and fascinating piece. It’s impossible not to be hypnotized by Jamie Muir’s opening marimba-like percussion made mostly of “found” pieces of metal and other random household objects, only to be scared back into one’s senses by David Cross’s menacing violin and finally assaulted by Fripp’s beast of a guitar riff. As Idris Elba says in Star Trek Beyond: “This is where the frontier pushes back.”

“Exiles” from Larks Tongues in Aspic

King Crimson’s discography is marked by a constant push and pull between musical beauty and ugliness. While the ugliness is marked by the band’s more explosive, improvisational moments, the beauty is among some of the most breathtaking in rock music. “Exiles” marks one of the most beautiful moments on an album perhaps most known for its deep musical probing into the unknown. “Exiles” emerges from a roiling stew of dark musical uncertainty and slips back into it occasionally, but each time it threatens to shed its beauty, Cross’s violin and Wetton’s voice illuminate the darkness. Wetton’s performance is particularly cathartic, a highlight of his oeuvre with or without King Crimson. It’s a wonder he was not more regularly hailed for his pure vocal talent – outside of his semi-stardom with Asia.

“The Night Watch” from Starless and Bible Black

Frank Zappa once said that writing about music is like dancing about architecture, but what does it sound like when you sing about a painting? Most of the Starless and Bible Black album is the aftermath of live improvisation later overdubbed in the studio, resulting in an intentionally challenging and often frustrating album (see “Frakture,” for God’s sake), but “The Night Watch” remains another one of Wetton’s highlights as a melodic interpreter of song. The song’s narrator, embodied by Wetton, is awestruck upon viewing Rembrandt’s titular painting, imploring the listener to appreciate the beauty found in such works through lyrics such as: “And so the pride of little men, the burghers good and true, still living through the painter’s hand, request you all to understand.”

“Starless” from Red

In 1974, Fripp saw the writing on the wall and decided that it was time for King Crimson to die. Punk rock was on its way, and sonically explorative bands like King Crimson were quickly going the way of the dodo. What better way to go out than in a blaze of glory? Pitchfork‘s Sam Sodomsky once described “Starless” as “Crimson’s own self-immolation” and, frankly there is no better description for the band’s original intended farewell statement. Fripp had no idea that King Crimson would be resurrected in six years (with a new lineup, of course), and on the closing track on the band’s most decidedly metal album, you can hear King Crimson playing what is essentially their own requiem, like Mozart dying from sheer artistic fatigue in Amadeus. King Crimson walks out, drops the match and lets the flames finish the job.

“Frame By Frame” from Discipline

Hearing Talking Heads for the first time clearly had an effect on Robert Fripp. In 1980, the same year Talking Heads released their undisputed masterpiece Remain in Light, Fripp decided to come out of semi-retirement to form a “new” group with King Crimson drummer Bill Bruford, session bassist Tony Levin (whom Fripp had met playing with Peter Gabriel) and guitarist/singer Adrian Belew, who was responsible for a large number of the more extreme guitar sounds on Talking Heads songs such as “The Great Curve.” Once the musicians realized that the group carried King Crimson’s adventurous spirit, the old name was applied to the new band. If Talking Heads would be brainteasers, the new King Crimson would operate with the same speed and precision at which neurons fire within the nervous system. “Frame By Frame” is King Crimson at their most shameless brain-scrambling. Strangely enough, though, once you’ve heard the song enough, it ceases to be scrambling. You expect every delayed drum hit; every shifted rhythm becomes part of one writhing musical organism, and you’ve just gotten a little smarter.

“Matte Kudasai” from Discipline

That same brain-scrambling lineup had to prove that they weren’t just all challenge, so they wrote the closest King Crimson has ever come to a straightforward love song. The title literally translates from Japanese as “Please wait.” In a case of reverse logic, perhaps writing something so straightforward was as radical and adventurous to them as writing an experimental piece is for most other bands, so for King Crimson, this was a huge leap. Leave it up to the band responsible for “21st Century Schizoid Man” to write something this placid and pristine. The only difference between this and previous moments of serenity in King Crimson’s discography is that whereas “Cadence and Cascade” and “Islands” were essentially acoustic songs based around solo guitar and piano, respectively, “Matte Kudasai” is a lush soundscape of layered electric guitars, all guided by Bruford’s gentle yet intricate drumming. Try asking a wedding band to play this after “Color My World.”