Lauren Drewes Daniels

Audio By Carbonatix

The news was quite a shock. When my doctor walked into the room in a full face shield and plastic smock that he wasn’t wearing when he left, my first thought was, “Is somebody painting somewhere or something? … Oh shit.”

“You’ve tested positive for COVID,” my doctor said.

It took a while for the news to settle. Once it did, I focused on getting myself home and letting my friends and family know so they could get tested. Fortunately, not a single one came back positive. I turned off Catholic guilt mode and went into self-preservation mode.

Even more fortunate, my case was a mild one. All I had to do is treat this like a serious flu by taking vitamins, staying hydrated and getting lots of rest. I also have to keep clear of people until Christmas Day. Considering the circumstances and outcomes surrounding my health and vaccination status, I’m fortunate that having to miss Christmas Day is the most annoying thing about getting COVID.

The symptoms did not take their time to arrive. My sinuses felt clogged as if by butter. My voice became scratchy and bumpy, turning my normal nasally tone into something like a soulless Morgan Freeman. Then my taste disappeared, and I don’t mean my love for putting stickers on everything and wearing band T-shirts under a sport coat.

My tongue is a blank canvas that cannot be painted. Foods of all kinds register nothing in my insular cortex, the part of the brain that registers tastes. I didn’t panic. I wasn’t even mildly disappointed that I couldn’t indulge in Ben & Jerry’s Mint Chocolate Cookie ice cream, the most delicious way in the world to treat a sore throat. Instead I became fascinated.

Science is still learning the whys and hows of COVID and its variants. This particular curious phenomenon is enlightening. Also, it’s either read up more on it or lie in bed and watch Barker-era Price is Right on PlutoTV until my eyes melt out of my skull.

The loss of smell and taste, also known as anosmia and ageusia respectively, is one of the most common and earliest symptoms of coronavirus. A study conducted by Vanderbilt University found that 73% of patients lost some degree of smell and taste when they contracted the virus.

Another study in the medical journal Cell suggests the virus targets a person’s taste and smell by attacking support and stem cells. Taste receptors “depend on rapid and reliable production” of these stem cells and other components. So when they run out, the sense of taste and smell lessen or disappear altogether.

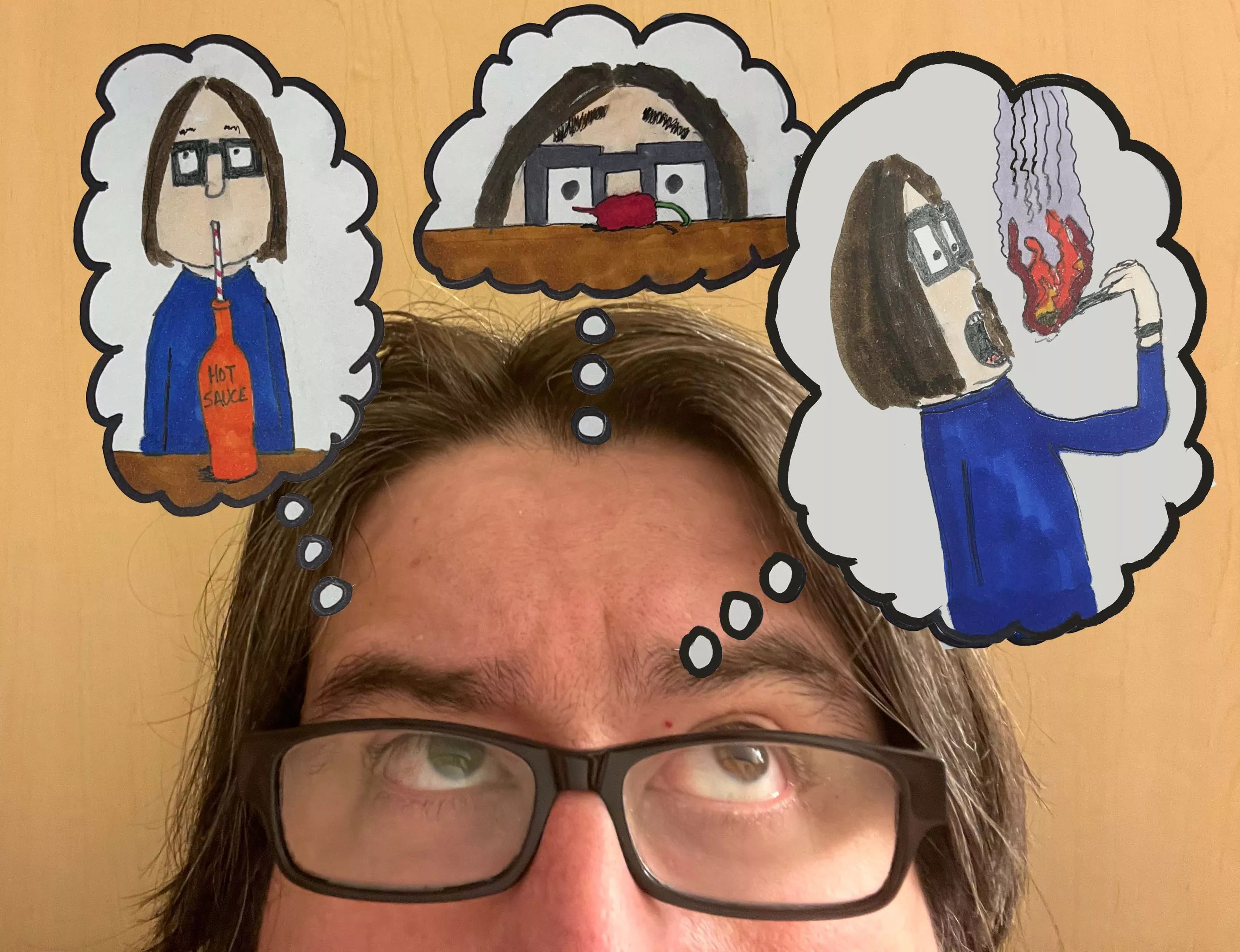

Yes, we had to tell Danny not to test his tasteless tongue by drinking hot sauce, chewing a Carolina Reaper pepper or eating fire.

Photo and drawings by Danny Gallagher

As soon as I realize my medical stage, I started trying stuff I had in my pantry and from the care packages friends and family dropped off. No matter what I tried, the blandness remained, but it felt like my brain was trying to remind me of memories of how things taste to replace the lack of a signature on my tongue. It’s like some kind of weird “phantom tongue” syndrome.

One reason for this could be because of a mental process called conditional taste aversion. The brain, nose and tongue are intimately connected to memories of flavors. According to a 2018 study in the World Journal of Otorhinolaryngology, these learned flavors are recorded to protect us from foods that made us feel sick or discomfort.

So this might explain why my brain reminds me of the cold rush of my favorite ice cream or the richness of a hot bowl of tomato soup. What happens if I taste something a little stronger?

“I could feel the pinching pain from the Atomic FireBall and the slight puckering from the Sour Patch Kids on the edge of my tongue.” – Danny Gallagher

My girlfriend dropped off a care package with a big bag of Sour Patch Kids gummies and a 100-count jar of Atomic FireBalls, a classic and underrated spicy cinnamon hard candy. The tastes were not as present when my receptors ran low on stem cells but the physical feelings they produce still jumped around my mouth. I could feel the pinching pain from the Atomic FireBall and the slight puckering from the Sour Patch Kids on the edge of my tongue. I even had to spit out the fireball at one point because the pain got too annoying, even if doing so threatened my masculinity.

I wanted to take it to Evel Knievel-sized heights of daredevil gustation. I asked my editor if I should eat a Carolina reaper, one of the hottest peppers on the planet with a Scoville level of 1.4 million. It’s something I’ve always wanted to try even if it kills me because I have a lot of pent-up adrenaline to burn but not enough spare change for a motorcycle. She suggested I dial it back a bit. So I bought the second, next scariest thing: yellow squash.

Squash is the one vegetable I cannot stand unless it’s hidden really well in other ingredients, but none of those ingredients can be any variety of squash. My mom used to boil it as a side for dinner and the squash’s nutty rind mixed with its blobby interior of blecch always made me feel physically ill. Squash, especially the yellow kind, sends my conditional taste aversion straight to DEFCON 1.

My blood pressure spiked as I ripped open the package and pulled a fresh yellow squash up to my mouth. I closed my eyes and took a healthy bite aaaaand … nothing. No gagging. No coughing. It tasted like any fresh vegetable even as my brain was trying to tell me that I’m basically eating the equivalent of farm-to-table poison.

It’ll take a while for my taste and smell to come back to their full ability, approximately four weeks depending on which study you’re reading or doctor you ask. Maybe it’ll teach me to be more open to foods farther out of my taste range and take the time to appreciate the things I eat and experience more once they return. Maybe it’ll make healthier things taste sweeter or more complicated.

The only thing I know will happen when my taste buds return is that I will consume every tasty thing in sight until I immediately regret doing so.

None of those things will be squash.