Mike Brooks

Audio By Carbonatix

The northeast exterior wall of Deep Ellum Self Storage, at 3215 Hickory St., is a 6,300-square-foot canvas covered in graffiti. The wall has 20 panels cloaked in letters drawn so intricately that only a graffiti artist could read them. That lettering is embellished with 3D styling and abstract, surrealist and semi-surrealist art by the best graffiti artists nationwide. Artist Pilot adds highlights to his work. Mike Brooks

Next to the lettering, classic New York-style graffiti colors the view from Interstate 30. A few panels down, an Aztec warrior princess crowned with a teal headdress confidently glares into the horizon. Soon, two Quetzalcoatl, feathered serpent gods, will join her. To her right, a meticulously detailed bison and horse navigate a mountainous landscape.

Across South Trunk Avenue, a 4,000-square-feet of brick wall is embellished with nostalgic touchstones: There’s Ella, from the 1988 psychological thriller Monkey Shines; Toy Story‘s Babyface; and Star Wars‘ Boba Fett.

This year, make your gift count –

Invest in local news that matters.

Our work is funded by readers like you who make voluntary gifts because they value our work and want to see it continue. Make a contribution today to help us reach our $30,000 goal!

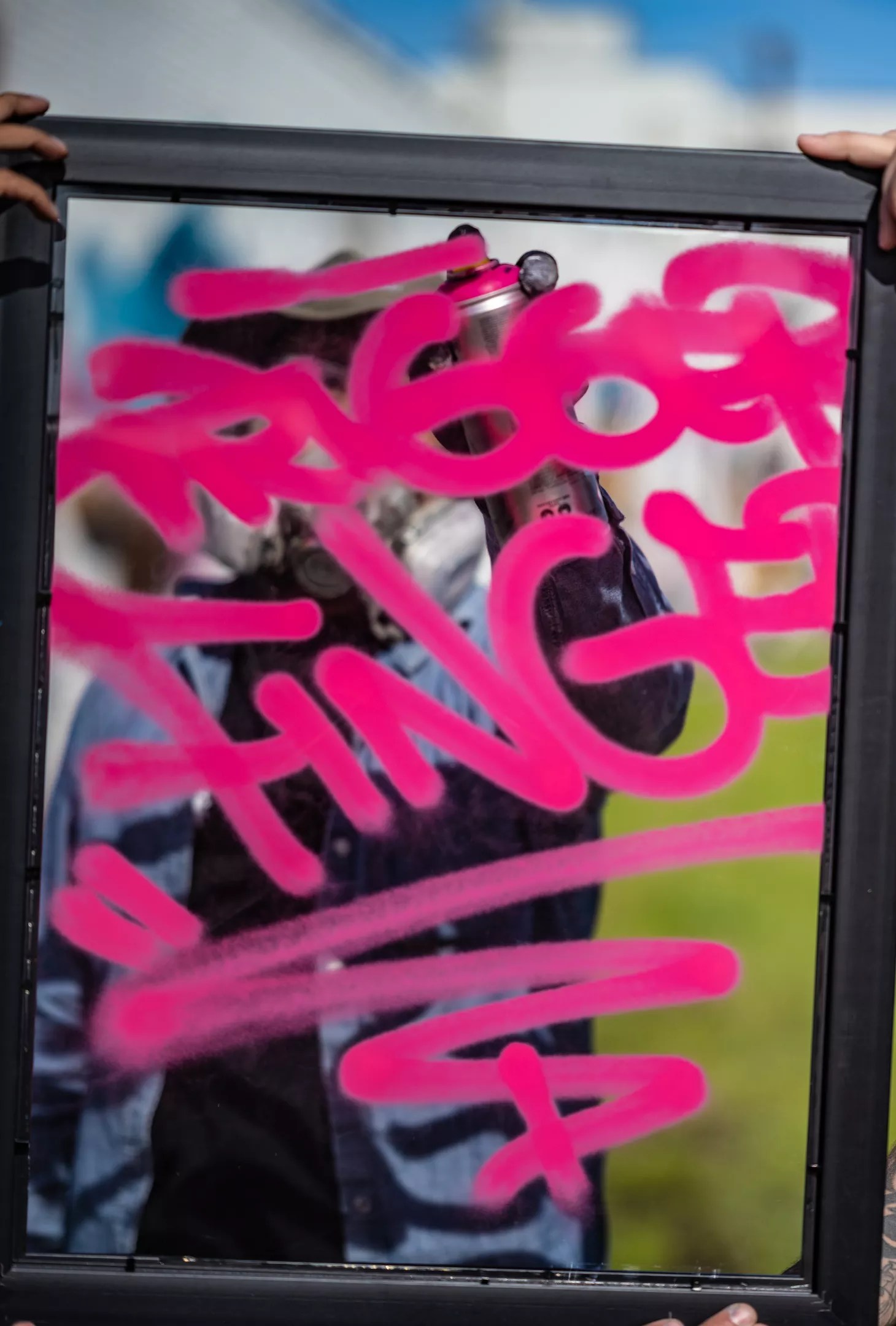

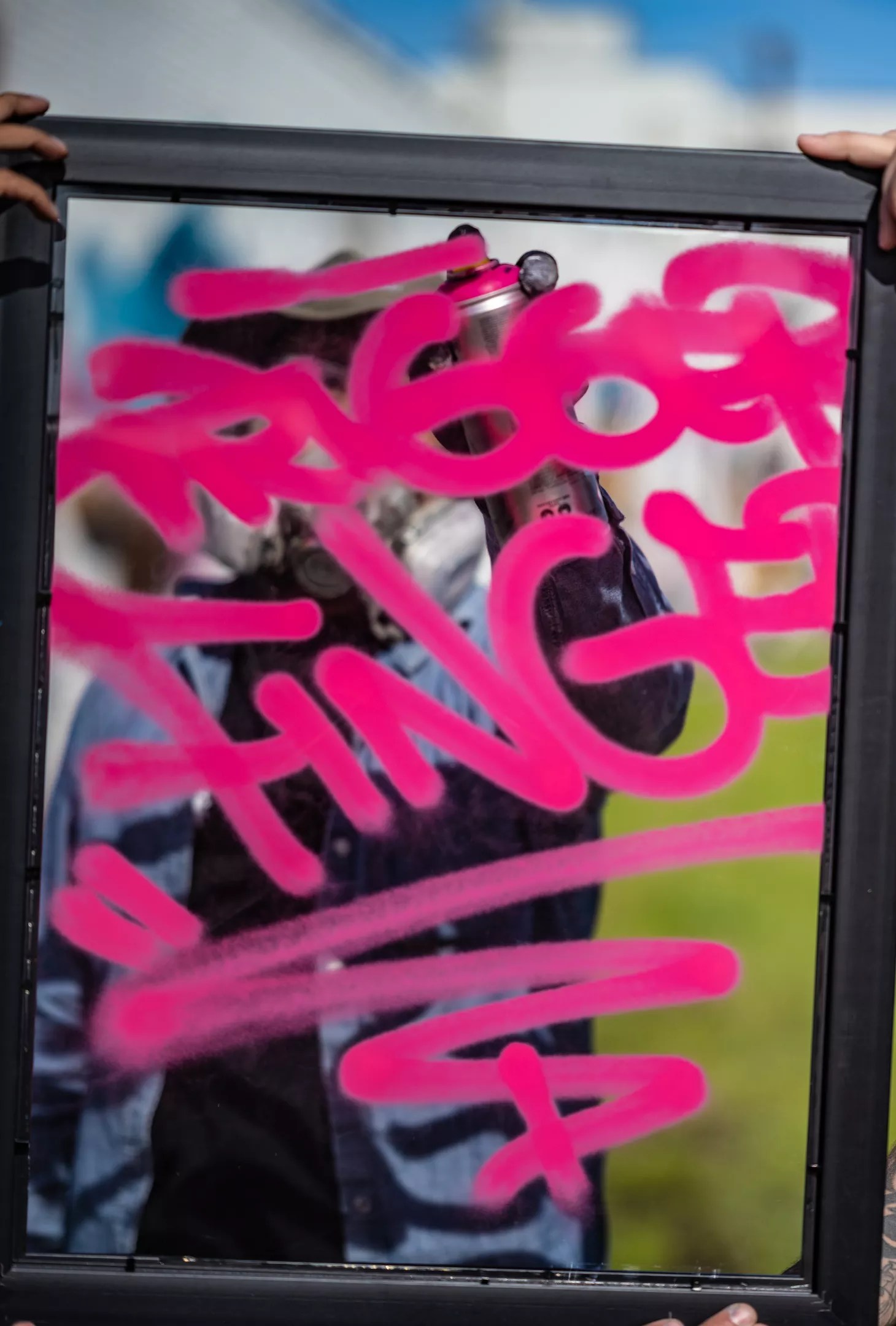

These walls are a canvas for Trigger Fingers, an annual invitation-only graffiti jam in Dallas. The event welcomes artists to use the space to create spray-painted artwork.

Trigger Fingers is a Dallas artist event where legal graffiti is enjoyed.

Mike Brooks

The fourth iteration of Trigger Fingers took form on Saturday, April 1, at Deep Ellum Self Storage. Fifty graffiti artists from Dallas and beyond participated in the largest Trigger Fingers graffiti jam to date this year. The public is invited to watch these artists in action as they create a sanctioned graffiti art production that celebrates graffiti as an art form.

“All this graffiti that you see on the freeways, the graffiti that you see on abandoned buildings, it’s an art form,” Trigger Fingers co-founder and graffiti artist Ray Albarez says. “It’s basically someone who wants to tell the world that they exist, that they’re here.”

Trigger Fingers was founded in 2019 by Albarez, along with graffiti artists Bobby Janss and Danny Dejong. The trio wanted to create an opportunity for artists to showcase the intricacies of works of graffiti when given resources, time and a legal space. The practice is a response against the respectability politics of the fine art realm, Albarez says, which has shunned graffiti art since its inception.

“A lot of street art wouldn’t be here if there wasn’t graffiti at the beginning,” he says.

While the artists are allowed to use the space for their event, graffiti in its purest form is illegal. Unsolicited markings and drawings on private or public property are considered a form of vandalism, so graffiti requires efficiency and a refined technique that allows artists to create complex stylized art in a timely manner without being caught.

“When you paint certain places, you’re not necessarily destroying anything,” Albarez says. “You’re actually leaving artwork.”

As a practice, graffiti is still in its relative infancy. In the 1970s, graffiti reached the New York City transit system when young people began spray painting the monikers they adopted onto the sides of subways stations and trains, for their names to be seen by thousands each day.

Graffiti soon took flight as “the written word of hip-hop,” according to Style Wars, a 1983 documentary on hip-hop culture.

Above: Contemporary artist Jeremy Biggers works on his graffiti at the event.

Mike Brooks

These names became infamous and sparked outrage among the public. Authorities responded by arresting artists, repainting trains, putting up barbed wire-topped fences and training German shepherds to ward off graffiti artists, according to the documentary.

“A lot of people see graffiti as more of a nuisance than an art form” says multi-disciplinary contemporary artist Jeremy Biggers. “Because of that, there is low-brow snubbing and people turning their nose up at the art form.”

In Dallas, illegal graffiti is punishable of up to 180 days in jail and a $2,000 fine, according to the Dallas police website.

By the ’80s and ’90s, graffiti crews became prominent. Camaraderie became central to graffiti artists.

“Your crew becomes an extension of your family,” Albarez says.

Albarez’s practice spans 25 years. He and Biggers are a part of Dallas’ Urban Army Crew, which was founded in 1995 and includes artists Hatziel Flores, Live, Twiz, Tercer, Trill, Snarf, Minqs, Brady and Mils. Their art can be found all over North Texas.

“Graffiti crews are an amalgamation of people that have felt outcast, have felt unheard, who felt they didn’t have a voice,” Biggers says.

Biggers doesn’t consider himself a graffiti artist. His involvement with Urban Army Crew has afforded him an understanding of the graffiti culture. There is a language, etiquette and hierarchy to which artists must adhere. Biggers respects it.

“If you didn’t grow up in that culture, if you didn’t come up with that respect, then it’s very difficult to figure it [the culture] out on your own,” Biggers says. “There kind of has to be an apprenticeship, at first.”

Talking with a graffiti artist requires an understanding of the lingo. Words like “tag,” “bomb,” “piece,” “throw-ups” or “throwies” and “productions” are a part of everyday language. They describe the type of work produced by an artist.

Graffiti artist Minqs works on her wall.

Mike Brooks

Tags are graffiti names painted onto a surface sans elaborate styling. Bombs, throwies and throw-ups are quick creations that are slightly more elaborate than tags, such as bubble letters. A piece layers elaborate coloring, outlines and 3D styling onto a tag. A production, the type of graffiti Trigger Fingers artists create at the event, includes a series of pieces with characters and drawings. Graffiti is street art. But not all street art is graffiti. Street art is the art of the masses, and the demand for it has skyrocketed.

Murals and graffiti work have long transformed Dallas’ scenery. The hands behind these creations often sprout from Dallas’ artist hubs. The West Dallas Tin District, a former industrial center, is the unofficial location of Dallas’ artist quarters. Here, more than 30 artists conduct their studio practice, in buildings adorned with graffiti work.

The Tin District is home to The Fabrication Yard, a legal graffiti park where experienced and amateur graffiti artists hone their craft, right next door to posh galleries.

Like the Tin District, the streets of Deep Ellum have flourished into a homegrown gallery of varied street art. It now boasts Deep Ellum Blues Alley, an expansive series of outdoor murals dedicated to Dallas’ blues music history, where muralists, graffiti artists and those who practice both art forms, such as Stalsby and Hatziel Flores, have contributed to Blues Alley.

The murals that color Deep Ellum are innumerable. The Deep Ellum Foundation estimates more than 100 murals are housed in the entertainment district. New murals are appearing as businesses commission artists’ works.

Trigger Fingers co-founder Ray Alberaz poses with his grafitti artwork.

Mike Brooks

“They’re [society] using something that we created that they [society] criminalized and now it’s a thriving business,” Albarez says. “Society wants to remove the fact that the whole street art movement started as graffiti.”

Commissioned street art often removes an artist’s creative freedom, he says. Those delegating the work generally have a vision they want the artist to imagine, whereas the independent nature of graffiti allows artists to create their individual styles that can skyrocket a career.

“A lot of the really good street artists, the well known ones, all started as graffiti artists,” Albarez says.

Shephard Fairey, famed for his “Hope” poster of President Barack Obama and his 1989 “Andre the Giant Has a Street Posse” campaign, has many ties to Dallas street art, even gifting Deep Ellum a painted water tower mural in 2021. He and Tristan Eaton, who is most known for his large scale patchwork style murals, found their footing in graffiti.

France, Denmark, Mexico, Sweden and hundreds of spaces in the U.S. are home to free-hand spray painted masterpieces by Eaton. Trigger Fingers’ 2022 wall was one of them.

As street art becomes commercialized and popularized, some definitions have become subjective. However, the use of spray paint alone doesn’t qualify a work as graffiti.

“Graffiti artists can be muralists, but a muralist cannot be a graffiti artist,” Albarez says.

The difference lies in the name. Graffiti artists adopt artistic names. For legal reasons, many keep these names confined to their graffiti circles. With these names comes an obligation to understand and comply with the culture behind graffiti.

“I joke with [graffiti artists] all the time,” Biggers says. “For graffiti to be such a rebellious art form, there’s too many rules.”

The most prominent rule is to have respect for the art.

Albarez says graffiti artists can tell when a work is refined. The line work is crisp, the artist’s control over the can is evident. Blends and transitions are smooth.

“The average person doesn’t understand that painting with spray is just as masterful, if not more masterful, than painting with a brush and using oil or acrylic,” Biggers says.

His own works have been influenced by the techniques he’s learned from his proximity to graffiti circles. He credits his adaptability and problem solving to the techniques he’s learned through graffiti work.

Among graffiti circles, respect is required for both seasoned artists and those who have mastered their craft. Certain works, like those at Trigger Fingers, are no-touch zones.

Dallas graffiti event Trigger Fingers’ founders: Bobby Janss, Danny Dejong and Ray Albarez

Mike Brooks

Edward Holman, owner of Deep Ellum Self Storage, says that before becoming the host site for Trigger Fingers, his property was often defaced. When Albarez approached him to request permission to use his wall, he hesitated. He feared the event would spark an onset of graffiti on his property. The opposite happened.

“There’s a hierarchy in the graffiti culture somewhere,” Holman says. “There’s been very little tagging now. The artists come and touch the artwork back up. There seems to be a good communication system.”

Last May, Urban Army Crew’s production was written over. Amateur markings of a jack-o-lantern, dolphin and horse, among other things, were placed over the seasoned crew’s masterpiece.

“Kids are dumb, kids make mistakes, but no matter your age you should know not to do this, you know this ain’t the spot for this,” the Trigger Fingers’ Instagram page posted.

On March 26, Deep Ellum Self Storage’s wall was wiped clean.

In anticipation of April 1, a thick coating of black exterior paint was applied over last year’s creations. Artists from IMOK Crew, DF Crew, Creatures Crew, MFK Crew, TITS Crew, Urban Army and individual artists like Ryan Stalby, Shiq, Beware and others met at the wall to create new artworks.

Beforehand, the artists of Trigger Fingers opened their exhibition called The Ones in the Chamber at Deep Ellum’s Umbrella Gallery, 2803 Taylor St. The exhibition runs until April 10.

For some, this exhibition will be the first time they’ll be working and showing arts on canvas. For many artists, it will be their first time invited into the gallery realm. And while the collective advocates for legitimizing graffiti, most artists will stay true to its nature and continue to leave their legacy on the city’s under dwellings and unsightly places.

“My art is going to live beyond my lifetime,” Albarez says. “That’s why I put my name up in as many places as I can. It’s to say, ‘Hey, I existed at this point in time.'”